Northumbria Research Link

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

And Concrete Island

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by York St John University Institutional Repository York St John University Beaumont, Alexander (2016) Ballard’s Island(s): White Heat, National Decline and Technology After Technicity Between ‘The Terminal Beach’ and Concrete Island. Literary geographies, 2 (1). pp. 96-113. Downloaded from: http://ray.yorksj.ac.uk/id/eprint/2087/ The version presented here may differ from the published version or version of record. If you intend to cite from the work you are advised to consult the publisher's version: http://literarygeographies.net/index.php/LitGeogs/article/view/39 Research at York St John (RaY) is an institutional repository. It supports the principles of open access by making the research outputs of the University available in digital form. Copyright of the items stored in RaY reside with the authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full text items free of charge, and may download a copy for private study or non-commercial research. For further reuse terms, see licence terms governing individual outputs. Institutional Repository Policy Statement RaY Research at the University of York St John For more information please contact RaY at [email protected] Beaumont: Ballard’s Island(s) 96 Ballard’s Island(s): White Heat, National Decline and Technology After Technicity Between ‘The Terminal Beach’ and Concrete Island Alexander Beaumont York St John University _____________________________________ Abstract: This essay argues that the early fiction of J.G. Ballard represents a complex commentary on the evolution of the UK’s technological imaginary which gives the lie to descriptions of the country as an anti-technological society. -

GOOD MORNING: 03/29/19 Farm Directionанаvan Trump Report

Tim Francisco <[email protected]> GOOD MORNING: 03/29/19 Farm Direction Van Trump Report 1 message The Van Trump Report <reply@vantrumpreportemail.com> Fri, Mar 29, 2019 at 7:14 AM ReplyTo: Jordan <replyfec01675756d0c7a314_HTML362509461000034501@vantrumpreportemail.com> To: [email protected] "Smooth seas do not make skillful sailors." African proverb FRIDAY, MARCH 29, 2019 1776, Putnam Named Printable Copy or Audio Version Commander of New York Troops On this day in 1776, Morning Summary: Stocks are slightly higher this morning but continue to consolidate General George Washington into the end of the first quarter, where it will post its best start to a new year since appoints Major General Israel 1998. It seems like the bulls are still trying to catch their breath after posting the Putnam commander of the troops in New massive rebound from December. The S&P 500 was up over +12% in the first quarter York. In his new capacity, Putnam was of 2019. We've known for sometime this would be a tough area technically. There's also expected to execute plans for the defense the psychological wave of market participants trying to get off the ride at this level, of New York City and its waterways. A having recouped most of what they lost in late2018. I mentioned many weeks ago, if veteran military man, Putnam had served we made it back to these levels it would get very interesting, as those who took the as a lieutenant in the Connecticut militia tumble would have an opportunity to get out of the market with most of their money during the French and Indian War, where back in their account. -

Jon Batiste and Stay Human's

WIN! A $3,695 BUCKS COUNTY/ZILDJIAN PACKAGE THE WORLD’S #1 DRUM MAGAZINE 6 WAYS TO PLAY SMOOTHER ROLLS BUILD YOUR OWN COCKTAIL KIT Jon Batiste and Stay Human’s Joe Saylor RUMMER M D A RN G E A Late-Night Deep Grooves Z D I O N E M • • T e h n i 40 e z W a YEARS g o a r Of Excellence l d M ’ s # m 1 u r D CLIFF ALMOND CAMILO, KRANTZ, AND BEYOND KEVIN MARCH APRIL 2016 ROBERT POLLARD’S GO-TO GUY HUGH GRUNDY AND HIS ZOMBIES “ODESSEY” 12 Modern Drummer June 2014 .350" .590" .610" .620" .610" .600" .590" “It is balanced, it is powerful. It is the .580" Wicked Piston!” Mike Mangini Dream Theater L. 16 3/4" • 42.55cm | D .580" • 1.47cm VHMMWP Mike Mangini’s new unique design starts out at .580” in the grip and UNIQUE TOP WEIGHTED DESIGN UNIQUE TOP increases slightly towards the middle of the stick until it reaches .620” and then tapers back down to an acorn tip. Mike’s reason for this design is so that the stick has a slightly added front weight for a solid, consistent “throw” and transient sound. With the extra length, you can adjust how much front weight you’re implementing by slightly moving your fulcrum .580" point up or down on the stick. You’ll also get a fat sounding rimshot crack from the added front weighted taper. Hickory. #SWITCHTOVATER See a full video of Mike explaining the Wicked Piston at vater.com remo_tamb-saylor_md-0416.pdf 1 12/18/15 11:43 AM 270 Centre Street | Holbrook, MA 02343 | 1.781.767.1877 | [email protected] VATER.COM C M Y K CM MY CY CMY .350" .590" .610" .620" .610" .600" .590" “It is balanced, it is powerful. -

Adventures of Engelbrecht, the 81 Advertising 77 Accelerationism 64

Index Adventures of Engelbrecht, The 81 “Prima Belladonna” 35 advertising 77 “Princess Margaret's Facelift” 41 accelerationism 64 “Project for a New Novel” 80–83, 101, 102 aesthetics 24, 32, 33 Rushing to Paradise 43 Ambit 102, 104 “Screen Game, The” 34–35 analogy 141, 143, 151, 152, 154 “Singing Statues, The” 33 Anderson, Benedict 11 “Studio 5, The Stars” 35 anti-imperialism 12, 20 “Summer Cannibals, The” 4 apocalyptic (post-apocalyptic) 2, 69, 71, Super-Cannes 48, 82 81, 83, 84 terminal documents 69, 72 Apollinaire, Guillaume 78, 81 “Terminal Beach, The” 2, 40–55, 82 archive 41–43 Vermilion Sands 2, 4, 24–39 atomic bomb 41–46, 48, 51, 54, 55 Ballard, Mary 79 Atwood, Margaret 2, 7 Bateson, Gregory 2, 87, 90–92, 94–97 Auden, W.H. 96 Baxter, Jeannette 52, 53, 101, 107, 113–114, 117 Augé, Marc 2, 6, 113, 115, 117–120, 141, 146 beach (beach fatigue) 4, 24, 34–38 non-place 113, 115, 117–120, 141, 146 Benjamin, Walter 65 avant-garde 7, 69, 70, 73, 83 Berardi, Franco 58, 59, 65 bicycle 70–1 Ballard, Fay 3, 7 Bikini Atoll 41, 43–44 “House-Clearance” 3 Blackburn, Simon 90n Ballard, J.G. blockhouses (concrete) 43, 45, 47 Atrocity Exhibition, The 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, Bloom, Harold 83 36–39, 40–45, 77–85, 87–97, 99, 101, 102, Bloom, Molly 75, 82 105, 107, 109, 110, 113–114, 127, 130 Bonsall, Mike 74 “Cloud Sculptors of Coral D, The” 29–32 borderzone 99, 100, 110 Concrete Island 41, 99 Boyer, M. -

Albright & O'malley Pre-CRS Dungan

February 8, 2010 Issue 178 Dungan: Lady A Sales Are Nuts HOLIDAY SC H EDULE Last week’s No. 1 all-genre debut of Lady Country Aircheck will be closed Monday, Feb. 15 in observance Antebellum’s Need You Now was fueled by of the President’s Day holiday. All Country Aircheck Mediabase a huge single, some crossover airplay and a monitored reporters can submit station adds any time from this national stage television performance, but Thursday (2/11) until 3pm ET/Noon PT on Tuesday, Feb. 16. Country Aircheck non-monitored Activator reporters may submit their 480,000 sold still caught some in the industry full reports any time during that same time frame. The Country by surprise. Country Aircheck spoke with Aircheck Weekly will be delivered Tuesday evening, Feb. 16. Capitol/Nashville President/CEO Mike Dungan for the stories behind the big story. When did you know it had the potential to be that big? Albright & O’Malley pre-CRS It was like losing your mind. It was gradually, then suddenly. McVay New Media Pres. Daniel That’s a quote. It felt big from the day we took it to Country Anstandig, dmr Pres./COO Tripp radio, certainly, and that it would be big with or without this Eldridge and Jaye Albright and Phillip pop exposure we had. Over the Thanksgiving weekend we Beswick are the newest additions to noticed some key pop stations were just playing it. With all this Albright & O’Malley’s annual pre-CRS consolidation, these guys are right next to each other and many Client Seminar. -

Liminal Space in J. G. Ballard's Concrete Island

Text Matters: A Journal of Literature, Theory and Culture Number 9 Roguery & (Sub)Versions Article 21 12-30-2019 Liminal Space in J. G. Ballard’s Concrete Island Marcin Tereszewski University of Wrocław Follow this and additional works at: https://digijournals.uni.lodz.pl/textmatters Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Tereszewski, Marcin. "Liminal Space in J. G. Ballard’s Concrete Island." Text Matters: A Journal of Literature, Theory and Culture, no.9, 2020, pp. 345-355, doi:10.18778/2083-2931.09.21 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Humanities Journals at University of Lodz Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Text Matters: A Journal of Literature, Theory and Culture by an authorized editor of University of Lodz Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Text Matters, Number 9, 2019 http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/2083-2931.09.21 Marcin Tereszewski University of Wrocław Liminal Space in J. G. Ballard’s Concrete Island A BSTR A CT This article explores the way in which surrealist techniques and assumptions underpin spatial representations in Ballard’s Concrete Island. With much of Ballard’s fiction using spatiality as an ideologically charged instrument to articulate a critique that underpins postcapitalist culture, it seems important to focus on exactly the kind of spaces that he creates. This paper will investigate the means by which spatiality is conceptualized in Ballard’s fiction, with special emphasis on places situated on the borders between realism and fantasy. -

23 February 2018 Page 1 of 8 SATURDAY 17 FEBRUARY 2018 Episode Five Agatha Christie Novel in a Poll in September 2015

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 17 – 23 February 2018 Page 1 of 8 SATURDAY 17 FEBRUARY 2018 Episode Five Agatha Christie novel in a poll in September 2015. Mary Ann has an unwelcome encounter with a presence from Directed by Mary Peate. SAT 00:00 BD Chapman - Orbiter X (b0784dyd) her past. Shawna is upset by Michael's revelation. First broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in 2010. Inside the Moon StationDr Max Kramer has tricked the crew of Dramatised by Lin Coghlan SAT 07:30 Byzantium Unearthed (b00dxdcs) Orbiter 2, but what exactly is Unity up to on the Moon? Producer Susan Roberts Episode 1Historian Bettany Hughes begins a series that uses the BD Chapman's adventure in the conquest of space in 14 parts. Director Charlotte Riches latest archaeological evidence to learn more about the empire of Stars John Carson as Captain Bob Britton, Andrew Crawford as For more than three decades, Armistead Maupin's Tales of the Byzantium and the people who ruled it. Captain Douglas McClelland, Barrie Gosney as Flight Engineer City series has blazed a trail through popular culture-from Bettany learns how treasures found in the empire's capital, Hicks, Donald Bisset as Colonel Kent, Gerik Schelderup as Max ground-breaking newspaper serial to classic novel. Radio 4 are modern-day Istanbul, reveal much about the life and importance Kramer, and Leslie Perrins as Sir Charles Day. With Ian Sadler dramatising the full series of the Tales novels for the very first of a civilisation that, whilst being devoutly Christian and the and John Cazabon. -

Body and Space in J. G. Ballard's Concrete Island and High-Rise

Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais Faculdade de Letras Pedro Henrique dos Santos Groppo Body and Space in J. G. Ballard’s Concrete Island and High-Rise Minas Gerais – Brasil Abril – 2009 Groppo 2 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Prof. Julio Jeha for the encouragement and support. He was always open and willing to make sense of my fragmentary and often chaotic ideas. Also, thanks to CNPq for the financial support. And big thanks to the J. G. Ballard online community, whose creativity and enthusiasm towards all things related to Ballard were captivating. Groppo 3 Abstract The fiction of J. G. Ballard is unusually concerned with spaces, both internal and exterior. Influenced by Surrealism and Freudian psychoanalysis, Ballard’s texts explore the thin divide between mind and body. Two of his novels of the 1970s, namely Concrete Island (1974) and High-Rise (1975) depict with detail his preoccupation with how the modern, urban world pushes man to the point where an escape to inner world is the solution to the tacit and oppressive forces of the external world. This escape is characterized by a suspension of conventional morality, with characters expressing atavistic tendencies, an effective return of the repressed. The present thesis poses a reading of these two novels, aided by analyses of some of Ballard’s short stories, with a focus on the relation between bodies and spaces and how they project and introject into one another. Such a reading is grounded on theories of the uncanny as described by Freud and highlights Ballard’s kinship to Gothic fiction. -

Dan Hutt 6/17/08 Uses of WWI Imagery in the Late 60'S Pop Music

Dan Hutt 6/17/08 Uses of WWI Imagery in the Late 60's Pop Music of the Zombies and the Royal Guardsmen Although very different bands, the British group the Zombies and the American group the Royal Guardsmen each played a part in the 1960's pop music phenomenon known as the British Invasion: the former as a key player in the cultural movement alongside bands such as the Beatles, the Kinks, and the Who, et al, and the latter as one of hundreds (if not thousands) of American groups who sought to emulate the new British beat sounds and styles. Each of the two groups embraced the jangly guitar sound and big vocal harmonies of the genre, but beyond those commonalities, shared little else. The Zombies enjoyed continued success throughout the 1960's and beyond, and were seen as not only producers of hit singles, but as a more substantive albums-oriented group. They remain widely respected to this day and have been hugely influential of countless other pop artists. The Royal Guardsmen, on the other hand, are generally regarded as having been a teenage kitsch or novelty act, riding the brief wave of popularity they enjoyed from the success of their "Snoopy"-related singles. The concern of this essay is the two groups' use of WWI imagery in some of their late 60's songs: the Royal Guardsmen's "Snoopy" songs (the primary four of which I will analyze here, dating from 1967-68) and the Zombies' song "Butcher's Tale (Western Front 1914)," from the acclaimed 1968 album, Odessey and Oracle. -

“I Am an Other and I Always Was…”

Hugvísindasvið “I am an other and I always was…” On the Weird and Eerie in Contemporary and Digital Cultures Ritgerð til MA-prófs í menningafræði Bob Cluness May 2019 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindad Menningarfræði “I am an other and I always was…” On the Weird and Eerie in Contemporary and Digital Cultures Ritgerð til MA-prófs í menningafræði Bob Cluness Kt.: 150676-2829 Tutor: Björn Þór Vilhjálmsson May 2019 Abstract Society today is undergoing a series of processes and changes that can be only be described as weird. From the apocalyptic resonance of climate change and the drive to implement increasing powerful technologies into everyday life, to the hyperreality of a political and media landscape beset by chaos, there is the uneasy feeling that society, culture, and even consensual reality is beginning to experience signs of disintegration. What was considered the insanity of the margins is now experienced in the mainstream, and there is a growing feeling of wrongness, that the previous presumptions of the self, other, reality and knowledge are becoming untenable. This thesis undertakes a detailed examination of the weird and eerie as both an aesthetic register and as a critical tool in analysing the relationship between individuals and an impersonal modern society, where agency and intention is not solely the preserve of the human and there is a feeling not so much of being to act, and being acted upon. Using the definitions and characteristics of the weird and eerie provided by Mark Fisher’s critical text, The Weird and the Eerie, I set the weird and eerie in a historical context specifically regarding both the gothic, weird fiction and with the uncanny, I then analyse the presence of the weird and the eerie present in two cultural phenomena, the online phenomenon of the Slender Man, and J.G. -

Picador January 2018

PICADOR JANUARY 2018 PAPERBACK ORIGINAL Babylon Berlin Book 1 of the Gereon Rath Mystery Series Volker Kutscher; translated by Niall Sellar An international bestseller, Babylon Berlin centers on a police inspector caught up in a web of drugs, sex, political intrigue, and murder in Berlin as Germany teeters on the edge of Nazism. It’s the year 1929 and Berlin is the vibrating metropolis of post-war Germany – full of bars and brothels and dissatisfied workers at the point of revolt. The strangest things happen here and the vice squad has its hands full. Gereon Rath FICTION / MYSTERY & is new in town and new to the department. Back in Cologne he was with the DETECTIVE / INTERNATIONAL MYSTERY & CRIME homicide department before he had to leave the city after firing a fatal shot. Picador | 1/23/2018 9781250187048 | $17.00 / $22.50 Can. When a dead man without an identity, bearing traces of atrocious torture, is Trade Paperback | 432 pages | Carton Qty: 28 discovered, Rath sees a chance to find his way back into the homicide division. 8.3 in H | 5.4 in W He discovers a connection with a circle of oppositional exiled Russians who try Other Available Formats: to purchase arms with smuggled gold in order to prepare a coup d’état. But there Ebook ISBN: 9781250187055 are other people trying to get hold of the gold and the guns, too. Raths finds himself up against paramilitaries and organized criminals. He falls in love with Charlotte, a typist in the homicide squad, and misuses her insider’s knowledge MARKETING for his personal investigations. -

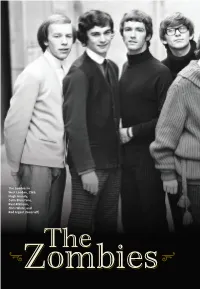

Hugh Grundy, Colin Blunstone, Paul Atkinson, Chris White, and Rod Argent (From Le )

The Zombies in West London, 1965: Hugh Grundy, Colin Blunstone, Paul Atkinson, Chris White, and Rod Argent (from le ) > The > 20494_RNRHF_Text_Rev1_70-95.pdfZombies 1 3/11/19 5:19 PM his year’s induction of the Zombies into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame is at once a celebration and a culmina- tion of one of the oddest and most convoluted careers in the history of popular music. While not the first band to have two smash hits right out of the box, they may be the only group who pro- ceeded to then fail miserably with their next ten sin- gles over a three-year period before finally achieving immortality with an album, Odessey [sic] and Oracle (1968) and a single, “Time of the Season,” that were released only after they had broken up. Even then, it would be a year after the album’s ini- tial release that, through the intercession of fate and Tthe idiosyncratic tastes of a handful of radio listeners in Boise, Idaho, “Time of the Season” would become a million-selling single and remain one of the most beloved staples of classic-rock radio to this day. Even more ironic was the fact that, despite that hit single, the album Odessey and Oracle was still met with indif- ference. Decades later, succeeding generations of crit- ics and an ever-growing cult fan base raised Odessey and Oracle to its status as one of the most cherished and revered albums of late 1960s British rock. As the album approached its fiftieth anniversary, four of the five original Zombies (guitarist Paul Atkinson passed away in 2004) went on tour, playing it in its entirety for sellout crowds throughout North America and the United Kingdom.