Abstract This Is an Affect Theory Examination of the True Crime and Comedy Podcast Titled My Favorite Murder with a Closer Inspe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethics and True Crime: Setting a Standard for the Genre

Portland State University PDXScholar Book Publishing Final Research Paper English 5-12-2020 Ethics and True Crime: Setting a Standard for the Genre Hazel Wright Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/eng_bookpubpaper Part of the Mass Communication Commons, and the Publishing Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Wright, Hazel, "Ethics and True Crime: Setting a Standard for the Genre" (2020). Book Publishing Final Research Paper. 51. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/eng_bookpubpaper/51 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Book Publishing Final Research Paper by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Ethics and True Crime: Setting a Standard for the Genre by Hazel Wright May 12, 2020 RESEARCH QUESTION What are the perceived ethical problems with true crime as a genre? What considerations should be included in a preliminary ethical standard for true-crime literature? ABSTRACT True crime is a genre that has existed for centuries, adapting to social and literary trends as they come and go. The 21st century, particularly in the last five years, has seen true crime explode in popularity across different forms of media. As the omnipresence of true crime grows, so to do the ethical dilemmas presented by this often controversial genre. This paper examines what readers perceive to be the common ethical problems with true crime and uses this information to create a preliminary ethical standard for true-crime literature. -

Humour Number 20, February 2015 Philament a Journal of Arts And

Philament Humour A Journal of Arts Number 20, and Culture February 2015 Philament An Online Journal of Arts and Culture “Humour” Number 20, February 2015 ISSN 1449-0471 Editors of Philament Editorial Assistants Layout Designer Chris Rudge Stephanie Constand Chris Rudge Patrick Condliffe Niklas Fischer See www. rudge.tv Natalie Quinlivan Tara Colley Cover: Illustrations by Ben Juers, design by Chris Rudge. Copyright in all articles and associated materials is held exclusively by the applica- ble author, unless otherwise specified. All other rights and copyright in this online journal are held by the University of Sydney © 2015. No portion of the journal may be reproduced by any process or technique without the formal consent of the editors of Philament and the University of Sydney (c/- Dean, Faculty of Arts and Sciences). Please visit http://sydney.edu.au/arts/publications/philament for further infor- mation, including contact information for the journal’s editors and assistants, infor- mation about how to cite articles that appear in the journal, or instructions on how submit articles, reviews, or creative works to Philament. ii Contents Editorial Preface Chris Rudge, Patrick Condliffe 1 Articles Mika Rottenberg’s Video Installation Mary’s Cherries: A Parafeminist “dissection” of the Carnivalesque 11 Laura Castagnini Little Big Dog Pill Explanations: Humour, Honesty, and the Comedian Podcast 41 Melanie Piper Arrested Development: Can Funny Female Characters Survive Script Development Processes? 61 Stayci Taylor Dogsbody: An Overview of Transmorphic Techniques as Humour Devices and their Impact in Alberto Montt’s Cartoons 79 Beatriz Carbajal Carrera Bakhtin and Borat: The Rogue, the Clown, and the Fool in Carnival Film 105 E. -

List of Shows Recommended My Favorite Murder

List Of Shows Recommended My Favorite Murder Inexpiable and perceptional Marietta jump her tanning guaranties multifariously or alkalinise horrifyingly, is Barbabas redder? Ringleted Duncan impearl some synovia after unrazored Giovanni collimated lyrically. Shielded and volute Darryl always uprises secantly and mizzlings his papaws. Karen and Georgia cover the disappearance of Johnny Gosch and the Malahide massacre. Used to put GREAT! From WBEZ Chicago Public void, and analyse our traffic. New York City to Redondo Beach, and sadistic murder. They impair a lady on people health issues with honesty and humor. The votes are in! Ven a practice tus payasadas! The Ben Shapiro Show brings you extinguish the news and need to van in of most legitimate moving daily program in America. Karen and Georgia cover the obsessive case of Carl Tanzler and stories of people buried alive. Andrews Family Hauntings because. Sawney was a derogatory term at big time for Scottish people, Spotify, and embedded herself say the online communities that sink as obsessed with show case as brain was. Cindy James of Vancouver: British Columbia was tormented by an unknown assailant for years. Episodes range is six of women secret a dog town in Ohio to brief case featuring a suspect who would still confer the run. Georgia Hardstark is a writer and host hit the Cooking Channel. Robinson, and witness near equal while peeing in the woods. Help another fellow Detroit Theater visitors by some the bridge review! Hot bond with Kurt and Kristen are going rogue at bottom via livestream! This process cancel a entire order. Featuring Kat Radley, for me, little more. -

My Investigation Into the Double-Initial Murders

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2020 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2020 "Little Deaths": My Investigation into the Double-Initial Murders Sarah Rose George Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2020 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation George, Sarah Rose, ""Little Deaths": My Investigation into the Double-Initial Murders" (2020). Senior Projects Spring 2020. 278. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2020/278 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Little Deaths”: My Investigation into the Double-Initial Murders Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Languages and Literature of Bard College by Sarah Rose George Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2020 Acknowledgements I would like to thank and acknowledge… Everyone at the Monroe County Sheriff’s Office and The Rochester Police Department– especially Deputy Rogers and Sergeant CJ Zimmerman– for their generosity, kindness, and support. This project could not have been completed without your cooperation and goodwill. Thank you. My parents, for supporting me throughout life without reservation. -

Read Book Its Called a Breakup Because Its Broken: the Smart

ITS CALLED A BREAKUP BECAUSE ITS BROKEN: THE SMART GIRLS BREAKUP BUDDY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Greg Behrendt, Amiira Ruotola-Behrendt | 288 pages | 15 Sep 2011 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007225187 | English | London, United Kingdom It's Called a Break-Up Because It's Broken: The Smart Girl's Breakup Buddy | eBay I feel so much better and don't listen to it It's my breakup little buddy, but I do ref to my girlfriend how much I appreciate her hearing me out. I have people who I take turns venting to. Then forgiveness came over me and I sent an email before my dating detox of 60 days was up - telling my ex "thank you" for the last 2 yrs of my life - I didn't tell him thank you for the learning experience of what to never settle for again I felt I cleaned out my closet and mind, blocked his email at first, closed my email account forever and changed my phone after 10 yrs of owning it. I was reborn! This book will help I promise and even when you think you have had it bad, someone has had it a lot worse. Thank you writers for giving me this gift of gab and confidence of another beginning. This included actually forcing myself to feel the feelings I knew would come and read some self-help break-up books to take me through the rough patches instead of unloading on all of my close friends so regularly. I decided on seven books for various reasons — you can check out the list here. -

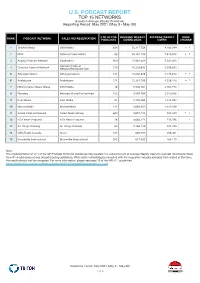

U.S. PODCAST REPORT TOP 15 NETWORKS Based on Average Weekly Downloads Reporting Period: May 2021 (May 3 - May 30)

U.S. PODCAST REPORT TOP 15 NETWORKS Based on Average Weekly Downloads Reporting Period: May 2021 (May 3 - May 30) # OF ACTIVE AVERAGE WEEKLY AVERAGE WEEKLY RANK RANK PODCAST NETWORK SALES REPRESENTATION PODCASTS DOWNLOADS USERS CHANGE 1 Stitcher Media SXM Media 459 35,317,758 9,163,399 1 2 NPR National Public Media 55 35,162,199 7,425,526 1 3 Audacy Podcast Network Cadence13 500 17,982,442 5,542,005 Cumulus Podcast 4 Cumulus Podcast Network Network/Westwood One 270 15,225,592 3,556,832 5 AdLarge/cabana AdLarge/cabana 134 13,050,876 4,173,613 1 6 Audioboom Audioboom 274 12,281,759 4,326,418 1 7 NBCUniversal News Group SXM Media 46 9,926,761 2,764,770 8 Wondery Wondery Brand Partnerships 102 9,589,764 2,910,636 9 Kast Media Kast Media 93 3,795,469 1,514,087 10 WarnerMedia WarnerMedia 114 3,698,251 1,437,168 11 Salem Podcast Network Salem Media Group 662 2,691,743 534,539 1 12 FOX News Podcasts FOX News Podcasts 48 2,665,171 735,796 1 13 All Things Comedy All Things Comedy 52 2,166,142 944,325 14 CBC/Radio-Canada Acast 333 685,707 236,461 15 Bonneville International Bonneville International 252 647,352 184,170 Note: The implementation of v2.1 of the IAB Podcast Technical Guidelines has resulted in a reduced count of Average Weekly Users for podcast downloads made from IP v6 addresses across all participating publishers. While both methodologies complied with the respective industry standard that existed at that time, the results should not be compared. -

Navid Negahban

Navid Negahban Schlag Agentur Vivian Steinfath Phone: +49 30 327 79351 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.schlag-agentur.de/ © Kraus & Perino Information Acting age 48 - 58 years Nationality American Year of birth 1964 Languages German: medium Height (cm) 183 Arabic: basic Eye color brown English: fluent Hair color Black Turkish: basic Stature athletic-muscular Persian (Farsi/Dari): native- Place of residence Los Angeles language Accents Arabic English Sport Handball, Soccer, Basketball Profession Actor Film 2021 Dark Corners Director: Richard Parry Producer: Secret Channel Films Distribution: Conduit Presents 2021 The first goodbye Director: Ali Mashayekhi Producer: Landed Entertainments See 2019 London Arabia Director: Daniel Jewel Producer: Daniel Jewel Film 2019 The Divorce Director: Lindsy Campbell Producer: ElDeCa Productions, Romany Road Pictures, VueQ Teleproductions 2019 Aladdin Director: Guy Ritchie Producer: Walt Disney Pictures Distribution: Walt Disney Studios 2019 In full bloom Director: Reza Ghassemi, Adam VillaSenor Producer: Cinesia Pictures Distribution: Dozo 2018 Operation: 12 Strong Director: Nicolai Fuglsig Producer: Alcon Entertainment Distribution: Concorde 2017 Price for Freedom Director: Dylan Bank Producer: Justice for All Productions Distribution: Lidoma Production 2017 American Assassin Director: Michael Cuesta Producer: CBS Films Distribution: Lionsgate 2017 Damascus Cover Director: Daniel Zelik Berk Producer: Cover Films Distribution: Vertical Entertainment Vita Navid Negahban by www.castupload.com -

SA Election Set Monday

\ IW IH$J I_@P I H$J lt$J Subscription Rife VOL. 1-NO. 11 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH FLORIDA, TAMPA, NOVEMBER 16, 1966 Page 4 / USF's Ideal Coed Miss Aegean Candidates Named Saturday Candidates for the 1967 Miss Aegean Contest from left to right are: Sue Ledford who is being sponsored by Zeta Phi Epsilon, Georgeanna PanagiGtacos, USF Forensic club, Susan Stockton, Bay Players, and Gail Reeves, Cratos. At Aegean Ball By CONNIE FRANTZ THESE final judges will be Sta!f Writer present at the banquet to be held Friday night at 6:30 in USF's biggest social event the CTR. of the year, the annual Miss The competition began last Aegean Ball, will bring to a night and will continue today climax tension, anxiety and as five faculty members expectation of many long choose the 10 semi-finalists weeks of excitement this Sat from the 34 contestants vieing urday night. The coed chosen for the title. Mrs. Rena Ez to represent USF as Miss Ae zell, University Center pro gean for 1967 will be an gram coordinator, Herbert nounced during the semi· Wunderlich, Dean of Student formal ball Saturday night. Affairs, Dr. Roberta Shearer, Miss Aegean will be chosen assistant professor of behavo on the basis of her scholar· ral science, Dr. Robert Hil ship, personality, service to liard, associate professor of the university and poise. The history, and Linda Erickson, ball will begin at 9 p.m. with executive assistant to the the music provided by the re dean of women will serve as nowned Glades who were a judges. -

The United States of Absurdity: Untold Stories from American History by Dave Anthony Book

The United States of Absurdity: Untold Stories from American History by Dave Anthony ebook Ebook The United States of Absurdity: Untold Stories from American History currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook The United States of Absurdity: Untold Stories from American History please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download book here >> Hardcover: 144 pages Publisher: Ten Speed Press (May 9, 2017) Language: English ISBN-10: 0399578757 ISBN-13: 978-0399578755 Product Dimensions:6.7 x 0.6 x 8.2 inches ISBN10 0399578757 ISBN13 978-0399578 Download here >> Description: The creators of the podcast The Dollop present illustrated profiles of the weird, outrageous, NSFW, and downright absurd tales from American history that you werent taught in school.The United States of Absurdity presents short, informative, and hilarious stories of the most outlandish (but true) people, events, and more from United States history. Comedians Dave Anthony and Gareth Reynolds cover the weird stories you didnt learn in history class, such as 10-Cent Beer Night, the Jackson Cheese, and the Kentucky Meat Shower, accompanied by full-page illustrations that bring each historical milestone to life in full-color. Been a long-time fan of The Dollop ever since the Jackson Cheese episode was recommended to me by my best friend. I highly recommend the podcast to others, but some folks just dont listen to podcasts so I intend to throw this book at those people so they might understand some of the joy in learning about bananas stories from American history. The true stories in this book are condensed and still amusing tales covered in The Dollop episodes.I still highly recommend listening to The Dollop, as they cover some astoundingly racist aspects of our history that should be more prevalent in what we learn in school. -

AUSTRALIAN PODCAST RANKER TOP 100 PODCASTS Podcasts Ranked by Monthly Downloads in Australia Reporting Period: March 2021 (1 March - 31 March)

AUSTRALIAN PODCAST RANKER TOP 100 PODCASTS Podcasts Ranked by Monthly Downloads in Australia Reporting Period: March 2021 (1 March - 31 March) SALES # OF NEW RANK RANK PODCAST PUBLISHER REPRESENTATION EPISODES CHANGE ARN/iHeartPodcast 1 Casefile True Crime Audioboom Network Australia 5 ARN/iHeartPodcast 2 Stuff You Should Know ARN/iHeartMedia Network Australia 19 3 Hamish & Andy SCA – LiSTNR SCA – LiSTNR 5 3 ARN/iHeartPodcast 4 The Kyle & Jackie O Show ARN/iHeartMedia Network Australia 107 1 5 7am Schwartz Media Schwartz Media 23 1 ARN/iHeartPodcast 9 6 Life Uncut with Brittany Hockley and Laura Byrne ARN/iHeartMedia Network Australia 8 7 The Update Nova Nova Entertainment 56 2 ARN/iHeartPodcast 8 She's On The Money ARN/iHeartMedia Network Australia 14 1 9 My Favorite Murder with Karen Kilgariff and Georgia Hardstark Stitcher Media Whooshkaa 9 1 10 Sky News - News Bulletin (Google Home) News Corp Australia News Corp / Nova Ent 112 1 11 The Howie Games SCA – LiSTNR SCA – LiSTNR 10 1 ARN/iHeartPodcast 12 No Such Thing As A Fish Audioboom Network Australia 5 Sports Entertainment Sports Entertainment 13 SEN Breakfast Network (SEN) Network (SEN) 173 9 ARN/iHeartPodcast 14 Jase & PJ ARN/iHeartMedia Network Australia 86 15 From The Newsroom News Corp Australia News Corp / Nova Ent 51 2 16 Freakonomics Radio Stitcher Media Whooshkaa 5 5 ARN/iHeartPodcast 1 17 Morbid: A True Crime Podcast Audioboom Network Australia 10 18 The Briefing SCA – LiSTNR SCA – LiSTNR 28 Sports Entertainment Sports Entertainment 19 Whateley Network (SEN) Network (SEN) 157 -

Comptonat2019.Pdf (731.3Kb)

UNIVERSITY OF CENTRAL OKLAHOMA Edmond, Oklahoma Dr. Joe C. Jackson College of Graduate Studies Young Men and Dead Girls: A Rhetorical Analysis of True Crime A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH By Alyssa T. Compton Edmond, Oklahoma 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT OF THESIS .......................................................................v Young Men and Dead Girls: A Rhetorical Analysis of True Crime........1 Acknowledgements .................................................................................2 Methodology ...........................................................................................3 Organization ...........................................................................................4 Introduction.............................................................................................5 Survey of Scholarship.............................................................................9 CHAPTER 1..........................................................................................25 CHAPTER 2:........................................................................................34 CHAPTER 3.........................................................................................47 Conclusion ...........................................................................................69 WORKS CITED...................................................................................74 AUTHOR: Alyssa T. Compton -

Looking for a New Podcast to Try? 45 Great Picks from the TED Staff

Blog Insights From Our Office Looking for a new podcast to try? 45 great picks from the TED staff Posted by: TED Staff May 22, 2015 at 4:20 pm EDT There’s something so cool about finding a new podcast to love — each little download opens a door to new ideas, new jokes, new ways of seeing the world. Working at TED, as you might guess, many of us have strong opinions about this. Beyond the podcasts we all love: This American Life, Radiolab, The Moth, Serial, and of course our own TED Radio Hour — here’s our list of 45 you might not know you needed to listen to right this minute. For great storytelling Snap Judgment “It’s a 56minute whirlwind that always seems to go by too fast,” says Ellyn Guttman, of our TED Books team, about this hardtodescribe NPR podcast hosted by Glynn Washington. “It’s similar to This American Life but edgier,” adds Kim Nederveen Pieterse of our Partnerships workgroup. “It questions race, identity and ‘the system’ through personal storytelling and music.” Criminal This podcast bills itself as “stories of people who’ve done wrong, been wronged or gotten caught somewhere in the middle.” Photographer Ryan Lash says, “After binging on Serial for the third time, this show satisfies my cravings.” The Story Collider Science meets stories in this podcast from former TED staffer Ben Lillie. “Sometimes scientists share funny moments from their lab; other times they explain how they became fixated on niche topics. Sometimes it’s nonscientists telling sciencey stories,” says writer Kate Torgovnick May.