Mission and Spiritual Mapping in Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STUDIES in DANIEL Preface

1 Endeavour Christian Gathering STUDIES IN DANIEL Preface In 2012 I led our Wednesday evening Bible study group at Endeavour Christian Gathering through the book of Daniel. These are my "teacher's notes". For these studies on Daniel I am greatly indebted to the work and writings of many others. Among many other commentaries and books, here is the bibliography on which I heavily relied: References Boice, J. (1989). Daniel. Grand Rapids, MI: Ministry Resources Library. Duguid, I. (2008). Daniel. Phillipsburg, N.J.: P & R Pub. Eaton, M. (n.d.). The Book of Daniel. 1st ed. Sovereign World. ESV: Study Bible, (2007). Wheaton, Ill: Crossway Bibles, pp:Daniel. Storms, S. (2014). Series Articles: Daniel. [online] Sam Storms - Enjoying God Ministries. Available at: http://www.samstorms.com/all-articles/keyword/daniel [Accessed 15 Dec. 2014]. Young, E. (1972). A commentary on Daniel. London, Eng.: Banner of Truth Trust. Max Randall Endeavour Christian Gathering, Perth, Western Australia 2 Endeavour Christian Gathering STUDIES IN DANIEL Introduction The Book of Daniel tends to be both familiar and unfamiliar to most Christians. The stories of Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego in the fiery furnace and Daniel in the lion’s den are among the most well-known Bible stories, even in this present age of widespread biblical illiteracy. These well-known stories display Daniel and his exiled Jewish friends standing firm for the Lord in the face of great adversity and hardship and so the average Christian has been taught to read those stories in a rather moralistic way in order to encourage them to “dare to be a Daniel” and live for Christ in a hostile world. -

The Course for World Christians

The Course for World Christians © 2003 DCI World Christians Network, England www.dci.org.uk This is the text only version with illustrations removed for quick downloading and ready formatted for easy printing with wide margins for your own notes. The complete Index of titles is on the next page. Please be sure to read the Information page at the end of this document To find out who we are please read the Find Out page at http://www.dci.org.uk/main/findout.htm These studies come to you free of charge as our offering in the love of Christ. Please pass them on to as many people as you can only remembering that "Freely you have received, therefore freely give." Thank you for taking these studies, and may God bless you as you study His word and discover some of His ways that I have learned for myself and now have the pleasure of sharing with you. Let me know how you get on via my direct line http://www.dci.org.uk/main/writetodci.htm Dr. Les Norman Author and editor of these notes - 1 - Titles and Lessons Lesson 1 Introduction to the Course Evangelism Lesson 2 Good News Lesson 3 Ask God Lesson 4 Preparation Points to Salvation Lesson 5 Lifestyle of the Evangelist Lesson 6 By All Means Lesson 8 Signs and Wonders Lesson 9 Heal the Sickness Lesson 10 Cast Out Demons Missions to the Ends of the Earth Lesson 11 God's Plan for the World Lesson 12 The Great Commission Lesson 13 The Last Command Lesson 14 What Is Mission? Lesson 15 God's Mission Promise Lesson 16 Finishing the Task Lesson 17 Unreached Peoples Lesson 18 Reaching the Unreached Lesson -

21 Day Daniel Fast

21 Day Daniel Fast Fasting Guidelines for 2017 Matthew 6:17-18 16 “When you fast, do not look somber as the hypocrites do, for they disfigure their faces to show others they are fasting. Truly I tell you, they have received their reward in full. 17 But when you fast, put oil on your head and wash your face, 18 so that it will not be obvious to others that you are fasting, but only to your Father, who is unseen; and your Father, who sees what is done in secret, will reward you. Kingdom Family International Church Pastors Valerie & Rodney Frazier Fasting Guidelines… For many years, Christians have fasted from food and observed other self-denying acts. The Bible teaches that some things come only by fasting and praying (Mark 9:29). Remember, you can pray without fasting however; you cannot truly fast without praying. Combining prayer with fasting connects the natural to the supernatural. Before Jesus started His earthly ministry, he went away and fasted for 40 days and 40 nights. So, if Jesus in all His deity fasted, being that He is: • Omnipresent – is everywhere at all times • Omniscient – is all knowing in every situation • Omnipotent – is all powerful in every fight How much more should fasting be a common practice in our lives? When we deny ourselves the comforts we are accustomed to—whether a full plate of food, or some other part of our daily routine (TV, coffee, Internet, etc.)— we are more mindful of our great need for God. Also, when we deny our sinful desires, we become more acutely aware of them, for when they are not fed, they tend to surface in more noticeable ways. -

Spiritual Warfare a Valley Bible Church Position Paper

Spiritual Warfare A Valley Bible Church Position Paper www.valleybible.net Christianity today is filled with speculation and outright wrong teaching about spiritual warfare. While certainly beliefs that are inconsistent with the Scripture ought to be corrected, speculations about the spirit realm should be avoided also. 2 Timothy 2:23 commands us to refuse to listen to foolish and ignorant speculations since they produce quarrels. 1 Timothy 1:4 teaches us that these speculations do not further God’s work of faith and are thus unprofitable. To engage in guesswork about the spirit realm or about any doctrine of the faith is simply wrong. The primary reason that Christians have allowed such speculation and errors regarding Satan is due to the value that so many people give to individual experiences. As experiences are reported, they are too readily accepted and added to the growing sum of accepted knowledge on the subject. Our perspective on spiritual warfare must come from God’s revealed Word and the Scripture must interpret our experience. Too often experiences are interpreting the Scripture. There are two basic errors that are being advocated today regarding spiritual warfare and result in a variety of problems. The first error involves the means of spiritual warfare and the second is regarding the timing of Christ’s victory over the devil. As to how we conduct spiritual warfare, the New Testament epistles teach us that our strategy of spiritual warfare against Satan is not to seek him out but to be on the alert, not to attack the devil but to resist the devil (1 Peter 5:8-9; James 4:7; Ephesians 6:11), particularly as we are tempted to indulge our fleshly desires. -

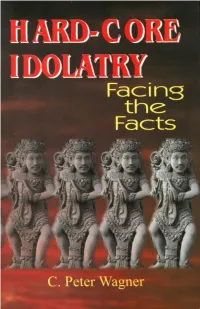

Hard-Core Idolatry: Facing the Facts Hard-Core Idolatry: Facing the Facts

HARD-CORE IDOLATRY: FACING THE FACTS HARD-CORE IDOLATRY: FACING THE FACTS C. PETER WAGNER Unless otherwise indicated, all Scripture quotations are from The New King James Version. Copyright © 1979, 1980, 1982, Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission. Hard-Core Idolatry: Facing the Facts Copyright © 1999 by C. Peter Wagner ISBN 0-9667481-4-X Published by Wagner Institute for Practical Ministry P.O. Box 62958 Colorado Springs, CO 80962-2958 Printed in the United States of America. All rights reserved under International Copyright Law. Contents and/or cover may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written consent of the publisher. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. IDOLATRY TODAY: LET'S GET SERIOUS.......................6 2. TRIVIALIZING IDOLATRY............................................. 9 3. SOFT-CORE IDOLATRY............................................. 14 4. BUT IDOLS ARE POWERLESS!....................................21 5. IDOLATRY NEXT DOOR.............................................27 6. LET'S DO SOMETHING ABOUT IT!.............................32 7. SPIRITUAL HOUSECLEANING...................................... 40 Chapter One 1. IDOLATRY TODAY: LET'S GET SERIOUS n my almost fifty years of walking the Christian walk, I have Iheard very few sermons on idolatry—hard-core idolatry, that is. The word "idolatry" is, in fact, used quite frequently by Christian leaders, but, unfortunately, a very small percentage of them are talking about idolatry the way the Bible talks about it. The Bible does have a great deal to say about blatant idolatry, and I believe we need to understand and deal with it much more seriously than we have been. THE 1990S ARE DIFFERENT Why do we need to be more aware of idolatry? It would be difficult to pinpoint any era since the Protestant Reformation in which the church as a whole has been more overtly engaged in spiritual warfare on the higher levels than we are in the decade of the 1990s. -

Regional Spirits? Contending with the King of Persia Lagrave Avenue Christian Reformed Church Aug

Regional Spirits? Contending with the King of Persia LaGrave Avenue Christian Reformed Church Aug. 26, 2018 – PM Sermon Rev. Peter Jonker Daniel 10:10-11:1 You may have noticed that my Bible text for today is the same as last week. This is not a mistake. As I prepared last week’s sermon on Daniel 10 I realized that this text was so rich, you could easily preach multiple sermons on it. And so that’s what I’ve decided to do. Last week we also mentioned that one of the features of apocalyptic literature is that it gives us a deeper view of reality. We tend to have a shallow view of life, we see things on the material plane, we focus on the physical realities in front of our eyes; apocalyptic literature wants us to see the deeper spiritual realities underneath the surface of things. To borrow from Ephesians 6, apocalyptic literature wants us to see our struggle is not with flesh and blood, but with the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly realms. Daniel 10 says some really interesting things about that spiritual struggle. Most of that centers around one character in this passage, the mysterious Prince of Persia. Let’s read the passage (Daniel 10). Who is this prince of Persia? Whoever he is, he must be pretty powerful, because the angel who comes to Daniel tells him that this mysterious prince has been resisting him for 21 days. And the angel is no weakling! In verse 6 of our passage we hear that the angel has a face like lightning and eyes like flaming torches. -

International Journal of Frontier Missions, Vol 10:4 Oct

Established in 1984 by the International INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF Student Leaders Coalition for Frontier Missions with the goal: “A Church For FRONTIER MISSIONS Every People By the Year 2000.” October 1993 Published January, April, July and October by the: International Student Volume 10 Number 4 Leaders Coalition for Frontier Missions P.O. Box 27266, El Paso, TX 79926, Contents USA 157 Editorial: Spiritual Warfare and the Frontiers Publisher: Hans M. Weerstra Bradley Gill 159 Romans as a Charter for World Missions Editor: Thomas Schirrmacher Hans M. Weerstra Associate Editors: 163 World View Clash: A Handbook for Spiritual Warfare Richard A. Cotton Edward F. Murphy D. Bruce Graham 169 Managing Editor: Animism, Secularism and Theism: Developing a Tripartite Model Judy Martines Weerstra Gailyn Van Rheenen 173Satan’s Tactics for Building and Maintaining His Kingdom of Darkness The International Journal of John Robb Frontier Missions (ISSN 0743-2429) promotes the serious investigation of 185 frontier mission issues including plans Power Encounter: Toward an SIM Position for world evangelization, measuring and monitoring progress in world Howard Brant evangelization, defining, publishing and profiling unreached peoples, 195 coordination of world evangelization Intercessors and Cosmic Urban Spiritual Warfare endeavors and the promotion of biblical Viv Grigg frontier mission theology. The Journal seeks to promote intergenerational 201Prayer Profile: The Bihari of India dialogue between senior and junior Adopt-A-People Clearinghouse mission leaders, cultivating an international fraternity of thought in the 203 Spiritual Warfare: Should it be Included in a Mission Curriculum? development of frontier missiology and Charles Laughlin advocating completion of world evangelization by AD 2000. -

Prayers That Bring Change – Kimberly Daniels

Prayers That Bring Change K I M B E R L Y D A N I E L S Confession For The Prosperity Of The Righteous Taken from Psalm 112 • Blessed is the man who fears the Lord. • The righteous man delights greatly in God's commandments. • The seed of the righteous shall be mighty upon the earth. • The generation of the upright shall be blessed. • Wealth and riches shall be in the house of the righteous. • The righteousness of the righteous man will endure forever. • A light shall arise in the midst of darkness for the righteous. • A good man shows favor and gives. • A good man guides his affairs with discretion. Contents Introduction: Apostle Kim's Personal "Blessed Prayer" SECTION I Prayers That Change Your Spiritual Life The "Commander of the Morning" Prayer Prayer for Divine Alignment Prayer for Spiritual Discernment Covenant Confession of the Word Prayer to Break Prayerlessness and Spiritual Slackness Prayer Against the Spirit of Coveting Breaking the Spirit of Betrayal Prayer to Recover From Emotional Damage Prayer for Spiritual Leaders The Fasting Prayer Prayer for Divine Health Prayer to Release Angels Minister's Confession Prayer for Intercessors Prayer for Revival on the Streets SECTION II Prayers That Change Business And The World The Gaza Prayer of Prosperity Prayer for Financial Blessings Marketplace Prayer Prayer for the U.S. Economy Prayer for President Barack Obama—the First American President of Color Prayer for the Political Atmosphere in America Prayer for Celebrities Prayer for Professional Athletes Prayer for Israel SECTION III -

Satan's Tactics in Building and Maintaining His Kingdom of Darkness

Satan’s Tactics in Building and Maintaining His Kingdom of Darkness Why are the unreached peoples still unreached? Is it because we haven’t understood Satan’s strategy, his schemes to blind and enslave whole peoples? If so, this article will help us understand our enemy and effectively hold his power in check and to liberate whole peoples on the face of the earth. By John Robb ost Christians feel a kind Satan’s Overall Program ence over government leaders, legal systems, educational systems, and M of reticence in considering Satan is a highly organized, intel- the operation of Satan and his religious movements. Admittedly, ligent spirit being dedicated to Scripture is not entirely lucid as kingdom. There is a hesitation, a destroying human beings made in kind of trepidation on our part to delve to how these spirits are organized or the image of the Creator he hates. He is how they operate, but there is into this unknown dark area of the master deceiver and the author reality we would prefer to avoid. None- enough Scriptural warrant to make of idolatry, seeking to bring the whole some conclusions regarding this. theless, it is part of the spiritual world under his dominion by warfare with which we must daily undermining faith in God, twisting Both Israel and the early church contend as believers, and so we values, and promoting false ideolo- perceived that God had given his would do well to understand as much gies. He does this through infiltrating angelic hosts a special role in the as we can since, in war, it may institutions, government adminis- administration of human affairs. -

A Quick Primer on Spiritual Warfare Copyright John Edmiston 2003 but May Be Copied & Distributed for Non-Profit Use

11 A Quick Primer On Spiritual Warfare Copyright John Edmiston 2003 but may be copied & distributed for non-profit use. Introduction The following short handbook covers the basics of spiritual warfare in the Filipino context. It is designed to be a handy reference work for pastors, elders, and missionaries and lay preachers. It covers most of the main topics in a concise form and is an assembling of various articles I have written over the years massaged into book form. It is from a bible-believing, born-again, charismatic Christian perspective but most Christians should find it helpful and it does not push any particularly divisive doctrines. The first section deals with the nature of the spiritual realms and the place of Christians in them and the nature of religions versus Christianity. Then we examine issues such as astrology, the occult, curses, hexes and spells, deliverance ministry. We then look at how to acquire and exert spiritual authority and do spiritual battle and cover a spiritual armory and how to use our weapons and the blood of Christ and be baptized in the Holy Spirit. Lastly we move into the topics of deliverance ministry and some of the ―weird stuff‖ such as the nature and types of angels and demons.. There is an index at the end to help you find your way around. The Battle Spiritual warfare is a battle between the kingdom of darkness ruled by Satan and the kingdom of light ruled by God and His Son Jesus Christ. The weapons of this warfare are not fleshly human weapons but spiritual weapons such as truth and righteousness, blessings and curses, forgiveness and repentance. -

Strategic Level Spiritual Warfare Don Fanning Liberty University, [email protected]

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Liberty University Digital Commons Liberty University DigitalCommons@Liberty University Trends and Issues in Missions Center for Global Ministries 2009 Strategic Level Spiritual Warfare Don Fanning Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgm_missions Recommended Citation Fanning, Don, "Strategic Level Spiritual Warfare" (2009). Trends and Issues in Missions. Paper 8. http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgm_missions/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Global Ministries at DigitalCommons@Liberty University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Trends and Issues in Missions by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Liberty University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Spiritual Warfare Movements P a g e | 1 Spiritual Warfare movements Just as the population has exploded over the past hundred years so one movement after another has spawn off the unanchored Pneuma ministries1. These began with the Wesleyan – Finney revivals which led to the Holiness – Pentecostal movements, through the First Wave, Second Wave and Third Wave movements which have now spawn the Strategic Level Spiritual Warfare (SLSW) movement. The theologies to support these and other movements are likewise as fluid. There is the Latter-Day Rain theology, Dominion Theology, Kingdom-Now Theology, Apostolic Reformation Theology, which use terms like “Manifest Sons of God,” “Joel’s Army,” and “IHOP.2” Overarching city-wide churches are in development to be led by modern-day apostles and prophets who purport to give contemporary revelations for believers in all the local churches, especially concerning the conquering of geographical demons and end-time prophecies. -

How the Christian Church in the United States Can Survive and Overcome Spiritual Warfare

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Doctor of Ministry Theses and Dissertations 3-2020 Believers Armor: How the Christian Church in the United States can Survive and Overcome Spiritual Warfare Michael A. Webb [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/dmin Part of the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Webb, Michael A., "Believers Armor: How the Christian Church in the United States can Survive and Overcome Spiritual Warfare" (2020). Doctor of Ministry. 394. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/dmin/394 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Ministry by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GEORGE FOX UNIVERSITY BELIEVERS ARMOR: HOW THE CHRISTIAN CHURCH IN THE UNITED STATES CAN SURVIVE AND OVERCOME SPIRITUAL WARFARE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF PORTLAND SEMINARY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MINISTRY BY MICHAEL A. WEBB PORTLAND, OREGON MARCH 2020 Portland Seminary George Fox University Portland, Oregon CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL ________________________________ DMin Dissertation ________________________________ This is to certify that the DMin Dissertation of Michael A. Webb has been approved by the Dissertation Committee on February 19, 2020 for the degree of Doctor of Ministry in Leadership and Global Perspectives Dissertation Committee: Primary Advisor: Darrell Peregrym, DMin Secondary Advisor: Phil Newell, DMin Lead Mentor: Jason Clark, PhD, DMin Copyright © 2020 Michael A. Webb All Rights Reserved. Unless otherwise noted, all Scripture quotations are from the ESV® Bible (The Holy Bible, English Standard Version®), copyright © 2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers.