The Nightmare Experience, Sleep Paralysis and Witchcraft Accusations1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluation of Depression and Anxiety, and Their Relationships with Insomnia, Nightmare and Demographic Variables in Medical Students

Sleep Hypn. 2019 Mar;21(1):9-15 http://dx.doi.org/10.5350/Sleep.Hypn.2019.21.0167 Sleep and Hypnosis A Journal of Clinical Neuroscience and Psychopathology ORIGINAL ARTICLE Evaluation of Depression and Anxiety, and their Relationships with Insomnia, Nightmare and Demographic Variables in Medical Students Alireza Haji Seyed Javadi1*, Ali Akbar Shafikhani2 1MD. of Psychiatry, Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Qazvin University of Medical Sciences, Qazvin, Iran 2Department of Occupational Health Engineering, Faculty of Health, Qazvin University of Medical Sciences, Qazvin, Iran ABSTRACT Researchers showed comorbidity of sleep disorders and mental disorders. The current study aimed to evaluate depression and anxiety and their relationship with insomnia, nightmare and demographic variables in the medical students of Qazvin University of Medical Sciences in 2015. The study population included 253 medical students with the age range of 18-35 years. Data were gathered using Beck depression inventory, Cattle anxiety, and insomnia and nightmare questionnaires and were analyzed by proper statistical methods (independent T-test, Chi-square test and Spearman correlation coefficient (P<0.05). Among the participants, 126 (49.6%) subjects had depression and 108 (42.5%) anxiety. The prevalence of depression and anxiety among the subjects with lower family income was significantly higher (X2=6.75, P=.03 for depression and X2=27.99, P<0.05 for anxiety). There was a close relationship between depression with sleep-onset difficulty, difficulty in awakening and daily sleep attacks, and also between anxiety with sleep-onset difficulty and daily tiredness (P <0.05). In addition, there was a close relationship between depression and anxiety with nightmare; 16.2% of the subjects with depression and 26.5% of the ones with anxiety experienced nightmares. -

The Russian Ritual Year and Folklore Through Tourist Advertising

THE RUSSIAN RITUAL YEAR AND FOLKLORE THROUGH TOURIST ADVERTISING IRINA SEDAKOVA This article analyzes the ritual year in modern Russia as Članek analizira praznično leto v moderni Rusiji, kot ga reflected in tourism spam letters circulated between 2005 odsevajo turistična oglasna sporočila med letoma 2005 in and 2012. These texts are the main source of data for this 2012. Tovrstna besedila so glavni vir podatkov za to študijo, study because they illustrate major tendencies in govern- saj odsevajo pomembnejše tendence vladnih, komercialnih mental, commercial, and individual attitudes towards in individualnih pogledov na ruske tradicionalne šege in Russian traditional customs and official holidays. They also uradne praznike. Prikazujejo tudi, kako se ohranja in demonstrate how local heritage is being maintained and rekonstruira lokalna dediščina in kako se pojavljajo in reconstructed, and how new myths and customs are appear- razvijajo novi miti in rituali, kot jih zahtevajo potrebe ing and developing to suit the needs of domestic tourism, a domačega turizma. special ethnographic calendrical type. Ključne besede: Rusija, praznično leto, pust, oglaševanje, Keywords: Russia, ritual year, carnival, advertising, tour- turistična antropologija, semiotika. ism anthropology, semiotics. INTRODUCTION This article focuses on the revitalization and re-invention of calendrical ritual celebrations in modern Russian provincial cities as a reciprocal process introduced by local authorities and tourist developers to motivate domestic tourists. This study touches on many sub- disciplines within anthropology, folklore, and linguistics. The topic partly fits into the anthropology of tourism, an academic discipline well established in Europe and the U.S. (core works are published in Smith 1989, Nash 1996, and Nash 2007 et al., but not yet presented in Russian academic investigation and teaching1). -

Sleeping Disorders and Anxiety in Academicians: a Comparative Analysis

Original Article / Özgün Makale DO I: 10.4274/jtsm.43153 Journal of Turkish Sleep Medicine 2018;5:86-90 Sleeping Disorders and Anxiety in Academicians: A Comparative Analysis Akademisyenlerde Uyku Bozuklukları ve Kaygı: Karşılaştırmalı Bir Analiz Nimet İlke Akçay, Anthony Awode, Mariyam Sohail, Yeliz Baybar, Kamal Alweithi, Milad Mahmoud Alilou, Mümtaz Güran Eastern Mediterranean University Faculty of Medicine, North Cyprus, Turkey Abstract Öz Objective: This study aims to examine the relationship between anxiety Amaç: Bu çalışma kaygı ve uyku bozuklukları arasındaki ilişkinin and sleep disorders and also to investigate the frequency of sleep irdelenmesini ve kaygı bozukluğu olanlarda uyku bozukluklarının disorders those with anxiety disorders among academicians who is a sıklığının kısıtlı bir çalışma grubu olan akademisyenlerde incelenmesini limited study group. hedeflemektedir. Materials and Methods: Two hundred and fifty academicians from Gereç ve Yöntem: Kampüsümüzdeki farklı fakültelerden 250 different faculties across our campus participated in the study with a akademisyen %47 erkek ve %53 kadın cinsiyet dağılımı ile çalışmaya gender distribution of 47% males and 53% females. The study was dahil edilmiştir. Çalışmada (i) demografik bilgiler, (ii) uyku evreleri ve conducted by a combined questionnaire which has four sections uyku kalitesi taraması, (iii) uyku bozukluklarının ölçeklendirilmesi, ve about (i) demographic information, (ii) sleep stages and sleep quality (iv) kaygı ölçeği olmak üzere 4 bölümden oluşan birleştirilmiş bir anket screening, (iii) scaling of sleep disorders and (iv) scale of anxiety. formu kullanılmıştır. Results: Anxiety in female and male participants was found to be 59% Bulgular: Kadın ve erkek popülasyonda kaygı sırası ile %59 ve %41 and 41% respectively. The total score of anxiety scale was positively olarak belirlenmiştir. -

Lucid Dreaming and the Feeling of Being Refreshed in the Morning: a Diary Study

Article Lucid Dreaming and the Feeling of Being Refreshed in the Morning: A Diary Study Michael Schredl 1,* , Sophie Dyck 2 and Anja Kühnel 2 1 Central Institute of Mental Health, Medical Faculty Mannheim/Heidelberg University, Zentralinstitut für Seelische Gesundheit, J5, 68159 Mannheim, Germany 2 Department of Psychology, Medical School Berlin, Calandrellistraße 1-9, 12247 Berlin, Germany * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-621-1703-1782 Received: 15 December 2019; Accepted: 10 February 2020; Published: 12 February 2020 Abstract: REM periods with lucid dreaming show increased brain activation, especially in the prefrontal cortex, compared to REM periods without lucid dreaming and, thus, the question of whether lucid dreaming interferes with the recovery function of sleep arises. Cross-sectional studies found a negative relationship between sleep quality and lucid dreaming frequency, but this relationship was explained by nightmare frequency. The present study included 149 participants keeping a dream diary for five weeks though the course of a lucid dream induction study. The results clearly indicate that there is no negative effect of having a lucid dream on the feeling of being refreshed in the morning compared to nights with the recall of a non-lucid dream; on the contrary, the feeling of being refreshed was higher after a night with a lucid dream. Future studies should be carried out to elicit tiredness and sleepiness during the day using objective and subjective measurement methods. Keywords: lucid dreaming; sleep quality; nightmares 1. Introduction Lucid dreams are defined as dreams in which the dreamer is aware that he or she is dreaming [1]. -

Physiological and Psychological Measurement of Sleep Disturbance in Female Trauma Survivors with PTSD and Major Depression

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Dissertations UMSL Graduate Works 7-25-2013 Physiological and Psychological Measurement of Sleep Disturbance in Female Trauma Survivors with PTSD and Major Depression Kimberly Borkowski Werner University of Missouri-St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://irl.umsl.edu/dissertation Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Werner, Kimberly Borkowski, "Physiological and Psychological Measurement of Sleep Disturbance in Female Trauma Survivors with PTSD and Major Depression" (2013). Dissertations. 306. https://irl.umsl.edu/dissertation/306 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the UMSL Graduate Works at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SLEEP DISTURBANCE IN FEMALES WITH PTSD AND DEPRESSION 1 Physiological and Psychological Measurement of Sleep Disturbance in Female Trauma Survivors with PTSD and Major Depression Kimberly B. Werner M.A, Psychology – Behavioral Neuroscience, University of Missouri – St. Louis, 2009 B.A., Psychology, Saint Louis University, 2006 A Dissertation Submitted at the University of Missouri – St. Louis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Psychology with an emphasis in Behavioral Neuroscience June 2013 Advisory Committee: Dr. Michael G. Griffin, Ph.D. Chairperson Dr. Tara E. Galovski, Ph.D. Dr. Joseph M. Ojile MD, D.ABSM, FCCP Dr. George Taylor, Ph.D. -

Sleep Disturbances in Patients with Persistent Delusions: Prevalence, Clinical Associations, and Therapeutic Strategies

Review Sleep Disturbances in Patients with Persistent Delusions: Prevalence, Clinical Associations, and Therapeutic Strategies Alexandre González-Rodríguez 1 , Javier Labad 2 and Mary V. Seeman 3,* 1 Department of Mental Health, Parc Tauli University Hospital, Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB), I3PT, Sabadell, 08280 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] 2 Department of Psychiatry, Hospital of Mataró, Consorci Sanitari del Maresme, Institut d’Investigació i Innovació Parc Tauli (I3PT), CIBERSAM, Mataró, 08304 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] 3 Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, #605 260 Heath St. West, Toronto, ON M5T 1R8, Canada * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 1 September 2020; Accepted: 12 October 2020; Published: 16 October 2020 Abstract: Sleep disturbances accompany almost all mental illnesses, either because sound sleep and mental well-being share similar requisites, or because mental problems lead to sleep problems, or vice versa. The aim of this narrative review was to examine sleep in patients with delusions, particularly in those diagnosed with delusional disorder. We did this in sequence, first for psychiatric illness in general, then for psychotic illnesses where delusions are prevalent symptoms, and then for delusional disorder. The review also looked at the effect on sleep parameters of individual symptoms commonly seen in delusional disorder (paranoia, cognitive distortions, suicidal thoughts) and searched the evidence base for indications of antipsychotic drug effects on sleep. It subsequently evaluated the influence of sleep therapies on psychotic symptoms, particularly delusions. The review’s findings are clinically important. Delusional symptoms and sleep quality influence one another reciprocally. Effective treatment of sleep problems is of potential benefit to patients with persistent delusions, but may be difficult to implement in the absence of an established therapeutic relationship and an appropriate pharmacologic regimen. -

Parasomnias Fact Sheet

Fact Sheet Parasomnias Overview Parasomnias are unusual things we do or experience while asleep or while partially asleep. Almost everyone has a nightmare from time to time. When someone has nightmares frequently, and they are very distressed about them, they may have Nightmare Disorder. Nightmare Disorder is considered a parasomnia since it is an unpleasant event that occurs while asleep. The term parasomnia is much broader than nightmares, and a person with Nightmare Disorder has more than just the occasional nightmare event. In addition to Nightmare Disorder, other common parasomnia events include: REM Behavior Disorder (RBD) Sleep paralysis Sleepwalking Confusional arousals What are common parasomnias? Typically parasomnias are classified by whether they occur during the rapid eye movement (REM) sleep or Non- REM sleep. People with an REM parasomnia are more likely to recall their unusual sleep behaviors (for example, nightmare) than those with a Non-REM parasomnia (for example, sleepwalking). REM Behavior Disorder (RBD) Most dreaming occurs in REM sleep. During REM sleep, most of our body muscles are paralyzed to prevent us from acting out our dreams. In REM Behavior Disorder (RBD), a person does not have this protective paralysis during REM sleep. Therefore, they might “act out” their dream. Since dreams may involve violence and protecting oneself, a person acting out their dream may injure themselves or their bed partner. The person will usually recall the dream, but not realize that they were actually moving while asleep. Sleep Paralysis and Sleep Hallucinations During REM sleep our muscles are paralyzed to keep us from acting out our dreams. -

BARTMIŃSKI, Jerzy: Úhel Pohledu, Perspektiva, Jazykový Obraz Světa

BARTMIŃSKI, Jerzy: Úhel pohledu, perspektiva, jazykový obraz světa. Martin Beneš Ústav pro jazyk český AV ČR, Praha [email protected] BARTMIŃSKI, Jerzy (1990): Punkt widzenia, perspektywa, językowy obraz świata. In: Jerzy Bartmiński (ed.), Językowy obraz świata. Lublin: Wydawnictwo UMCS, s. 109–127. BARTMIŃSKI, Jerzy (2009): Punkt widzenia, perspektywa, językowy obraz świata. In: Jerzy Bartmiński, Językowe podstawy obrazu świata. Lublin: Wydawnictwo UMCS, s. 76–88. Teorie jazykového obrazu světa, která je důležitou součástí výzkumného programu etnolingvistiky, je rozšířena ve dvou odlišných variantách, které lze zjednodušeně označit jako varianty „subjektivní“ a „objektivní“. Tyto varianty lze následně usouvztažnit s pojmy vidění světa (anglicky view of the world) a obraz světa (německy das sprachliche Weltbild). Vidění, tj. jistý pohled na svět, je vždy viděním někoho, implikuje dívání se, a tím i vnímající subjekt. Na druhou stranu obraz, i když je také výsledkem vnímání světa určitou osobou, subjekt sám o sobě tak silně neimplikuje; těžiště je v jeho rámci přesunuto na objekt, tedy na to, co je zahrnuto přímo v samotném jazyku. To však neznamená, že bychom v případě konkrétních subjektů mohli hovořit jen o jejich vidění světa, můžeme naopak – sice poněkud zprostředkovaně – hovořit i o jejich obrazu světa, tj. např. o obrazu světa dětí, „prostých“ lidí, úředníků nebo Evropanů. Můžeme dokonce klasifikovat jazykové obrazy světa podle toho, kdo jsou jejich tvůrci a nositelé, jak to navrhuje V. I. Postovalovová.1 Oba pojmy z titulu tohoto článku – úhel pohledu i perspektiva – se tedy vztahují jak k „vidění světa“, tak i k „obrazu světa“. Rekonstrukcí jazykového obrazu světa subjektů určitého kulturního společenství, které bývá označováno tradičním spojením „polský lid“, by měl být v Lublinu připravovaný Słownik ludowych stereotypów językowych [Slovník lidových jazykových stereotypů] (SLSJ, 1980). -

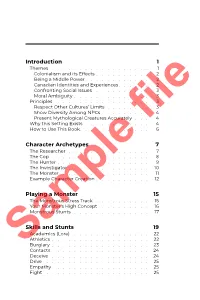

Introduction 1 Character Archetypes 7 Playing a Monster 15 Skills

Introduction 1 Themes..................1 Colonialism and its Effects..........2 Being a Middle Power............2 Canadian Identities and Experiences......2 Confronting Social Issues..........3 Moral Ambiguity..............3 Principles.................3 Respect Other Cultures’ Limits........3 Show Diversity Among NPCs.........4 Present Mythological Creatures Accurately...4 Why this Setting Exists............4 How to Use This Book.............6 Character Archetypes 7 The Researcher...............7 The Cop..................8 The Hunter.................9 The Investigator............... 10 The Monster................ 11 Example Character Creation.......... 12 Playing a Monster 15 The Monstrous Stress Track.......... 15 Your Monster’s High Concept......... 16 Monstrous Stunts.............. 17 Skills and Stunts 19 Academics (Lore).............. 22 Athletics.................. 22 SampleBurglary.................. 23 file Contacts.................. 24 Deceive.................. 24 Drive................... 25 Empathy.................. 25 Fight................... 25 Investigate................. 26 Notice................... 26 Physique.................. 27 Provoke.................. 27 Rapport.................. 28 Resources................. 28 Shoot................... 28 Stealth................... 30 Tech (Crafts)................ 30 Will.................... 31 Earth’s Secret History 33 Veilfall................... 33 Supernatural Immigration........... 35 The Cerulean Amendment.......... 36 Lifting the Veil................ 36 Organizations and NPCs 39 -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research (ASSEHR), volume 312 International Conference "Topical Problems of Philology and Didactics: Interdisciplinary Approach in Humanities and Social Sciences" (TPHD 2018) Between Folklore and Literature: Mastery of A.N. Tolstoy-Storyteller (on the 135th anniversary of the writer) Varvara A. Golovko Evgenia A. Zhirkova Dept. of History of the Russian literature, theory of Dept. of History of the Russian literature, theory of literature and criticism literature and criticism Kuban State University Kuban State University Krasnodar, Russia Krasnodar, Russia [email protected] [email protected] Natalya V. Svitenko Dept. of History of the Russian literature, theory of literature and criticism Kuban State University Krasnodar, Russia [email protected] Abstract–The study of the interaction of traditional folk unfortunately incomplete project of the author, set of folk culture and professional art, folklore and literature for more tales. After the publication of the lyric collections, readers than a century is considered to be one of the main directions of became acquainted with the cycle “Magpie’s Tales”, first humanitarian knowledge. The article is devoted to the analysis of published by the St. Petersburg Publishing House “Public the author’s transformations of Russian folklore in the “fairy- Benefit” in 1910. tale” works of Alexei Nikolaevich Tolstoy (1883-1945). The relevance of the research is determined by the special role of Many times for different literary collections, the author has folklore images, motifs and plot patterns in the writer's works. rewritten the cycle “Magpie’s Tales”. In the Complete Works, The folklore-mythological aspect of the works of the “third” the authors of the comments note that “in 1923, when the State Tolstoy is less studied by scholars, although in a number of works Publishing house published a collection of fairy tales and about the writer there are judgments about the general influence poems by A. -

Pagan Beliefs in Ancient Russia. by Luceta Di Cosimo, Barony Marche of the Debatable Lands, Aethelmearc

1 Pagan Beliefs in Ancient Russia. By Luceta di Cosimo, Barony Marche of the Debatable Lands, Aethelmearc. [email protected] ©2006-2017 Slavic mythology is a difficult subject. The historical evidence is fragmented, with many conflicting sources and multiple later literary inventions. This is a brief reconstruction of ancient Russian mythology. The first archaeological findings that can be attributed to Slavs date to approximately 6th c. AD. The origins of Slavs are still debated. The pagan Slavic society was an oral society. Christianity, which introduced writing, was more concerned with eradication rather than preservation of pagan beliefs. No one really tried to preserve and record whatever remained, until late period. Then, there is some evidence recorded from the Germans who visited Russia in 18th c., but a lot of it is based on the written 15thc. sources, rather than eyewitness accounts. The 19th c. Europe saw renewed interest in folklore, and combined with rise of nationalism and need for developed mythos, a lot of what was left was recorded, but a lot was altered to make it more palatable, and questionable things (especially with fertility rituals) were edited out as not to besmirch the emerging national character. During the Soviet time, the study of any religion was problematic, due to mandatory atheism. Eventually, the study of the early Slavic traditions was permitted, and even encouraged, but, everything had to pass stringent censorship rules, and could not contradict Marxist-Leninist philosophy. So, people who had the material (in the USSR) could not publish, and people who actually could publish (in the West) did not have access to the materials. -

Slavic Pagan World

Slavic Pagan World 1 Slavic Pagan World Compilation by Garry Green Welcome to Slavic Pagan World: Slavic Pagan Beliefs, Gods, Myths, Recipes, Magic, Spells, Divinations, Remedies, Songs. 2 Table of Content Slavic Pagan Beliefs 5 Slavic neighbors. 5 Dualism & The Origins of Slavic Belief 6 The Elements 6 Totems 7 Creation Myths 8 The World Tree. 10 Origin of Witchcraft - a story 11 Slavic pagan calendar and festivals 11 A small dictionary of slavic pagan gods & goddesses 15 Slavic Ritual Recipes 20 An Ancient Slavic Herbal 23 Slavic Magick & Folk Medicine 29 Divinations 34 Remedies 39 Slavic Pagan Holidays 45 Slavic Gods & Goddesses 58 Slavic Pagan Songs 82 Organised pagan cult in Kievan Rus' 89 Introduction 89 Selected deities and concepts in slavic religion 92 Personification and anthropomorphisation 108 "Core" concepts and gods in slavonic cosmology 110 3 Evolution of the eastern slavic beliefs 111 Foreign influence on slavic religion 112 Conclusion 119 Pagan ages in Poland 120 Polish Supernatural Spirits 120 Polish Folk Magic 125 Polish Pagan Pantheon 131 4 Slavic Pagan Beliefs The Slavic peoples are not a "race". Like the Romance and Germanic peoples, they are related by area and culture, not so much by blood. Today there are thirteen different Slavic groups divided into three blocs, Eastern, Southern and Western. These include the Russians, Poles, Czechs, Ukrainians, Byelorussians, Serbians,Croatians, Macedonians, Slovenians, Bulgarians, Kashubians, Albanians and Slovakians. Although the Lithuanians, Estonians and Latvians are of Baltic tribes, we are including some of their customs as they are similar to those of their Slavic neighbors. Slavic Runes were called "Runitsa", "Cherty y Rezy" ("Strokes and Cuts") and later, "Vlesovitsa".