ESSAYS in the HISTORY of LANGUAGES and LINGUISTICS Dedicated to Marek Stachowski on the Occasion of His 60Th Birthday

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drunkenness and Ambition in Early Seventeenth-Century Scottish Literature," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 35 | Issue 1 Article 12 2007 Drunkenness and Ambition in Early Seventeenth- Century Scottish Literature Sally Mapstone St. Hilda's College, Oxford Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Mapstone, Sally (2007) "Drunkenness and Ambition in Early Seventeenth-Century Scottish Literature," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 35: Iss. 1, 131–155. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol35/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sally Mapstone Drunkenness and Ambition in Early Seventeenth-Century Scottish Literature Among the voluminous papers of William Drummond of Hawthomden, not, however with the majority of them in the National Library of Scotland, but in a manuscript identified about thirty years ago and presently in Dundee Uni versity Library, 1 is a small and succinct record kept by the author of significant events and moments in his life; it is entitled "MEMORIALLS." One aspect of this record puzzled Drummond's bibliographer and editor, R. H. MacDonald. This was Drummond's idiosyncratic use of the term "fatall." Drummond first employs this in the "Memorialls" to describe something that happened when he was twenty-five: "Tusday the 21 of Agust [sic] 1610 about Noone by the Death of my father began to be fatall to mee the 25 of my age" (Poems, p. -

BARTMIŃSKI, Jerzy: Úhel Pohledu, Perspektiva, Jazykový Obraz Světa

BARTMIŃSKI, Jerzy: Úhel pohledu, perspektiva, jazykový obraz světa. Martin Beneš Ústav pro jazyk český AV ČR, Praha [email protected] BARTMIŃSKI, Jerzy (1990): Punkt widzenia, perspektywa, językowy obraz świata. In: Jerzy Bartmiński (ed.), Językowy obraz świata. Lublin: Wydawnictwo UMCS, s. 109–127. BARTMIŃSKI, Jerzy (2009): Punkt widzenia, perspektywa, językowy obraz świata. In: Jerzy Bartmiński, Językowe podstawy obrazu świata. Lublin: Wydawnictwo UMCS, s. 76–88. Teorie jazykového obrazu světa, která je důležitou součástí výzkumného programu etnolingvistiky, je rozšířena ve dvou odlišných variantách, které lze zjednodušeně označit jako varianty „subjektivní“ a „objektivní“. Tyto varianty lze následně usouvztažnit s pojmy vidění světa (anglicky view of the world) a obraz světa (německy das sprachliche Weltbild). Vidění, tj. jistý pohled na svět, je vždy viděním někoho, implikuje dívání se, a tím i vnímající subjekt. Na druhou stranu obraz, i když je také výsledkem vnímání světa určitou osobou, subjekt sám o sobě tak silně neimplikuje; těžiště je v jeho rámci přesunuto na objekt, tedy na to, co je zahrnuto přímo v samotném jazyku. To však neznamená, že bychom v případě konkrétních subjektů mohli hovořit jen o jejich vidění světa, můžeme naopak – sice poněkud zprostředkovaně – hovořit i o jejich obrazu světa, tj. např. o obrazu světa dětí, „prostých“ lidí, úředníků nebo Evropanů. Můžeme dokonce klasifikovat jazykové obrazy světa podle toho, kdo jsou jejich tvůrci a nositelé, jak to navrhuje V. I. Postovalovová.1 Oba pojmy z titulu tohoto článku – úhel pohledu i perspektiva – se tedy vztahují jak k „vidění světa“, tak i k „obrazu světa“. Rekonstrukcí jazykového obrazu světa subjektů určitého kulturního společenství, které bývá označováno tradičním spojením „polský lid“, by měl být v Lublinu připravovaný Słownik ludowych stereotypów językowych [Slovník lidových jazykových stereotypů] (SLSJ, 1980). -

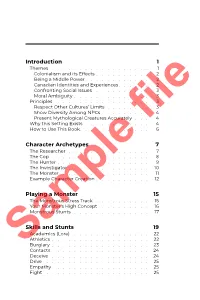

Introduction 1 Character Archetypes 7 Playing a Monster 15 Skills

Introduction 1 Themes..................1 Colonialism and its Effects..........2 Being a Middle Power............2 Canadian Identities and Experiences......2 Confronting Social Issues..........3 Moral Ambiguity..............3 Principles.................3 Respect Other Cultures’ Limits........3 Show Diversity Among NPCs.........4 Present Mythological Creatures Accurately...4 Why this Setting Exists............4 How to Use This Book.............6 Character Archetypes 7 The Researcher...............7 The Cop..................8 The Hunter.................9 The Investigator............... 10 The Monster................ 11 Example Character Creation.......... 12 Playing a Monster 15 The Monstrous Stress Track.......... 15 Your Monster’s High Concept......... 16 Monstrous Stunts.............. 17 Skills and Stunts 19 Academics (Lore).............. 22 Athletics.................. 22 SampleBurglary.................. 23 file Contacts.................. 24 Deceive.................. 24 Drive................... 25 Empathy.................. 25 Fight................... 25 Investigate................. 26 Notice................... 26 Physique.................. 27 Provoke.................. 27 Rapport.................. 28 Resources................. 28 Shoot................... 28 Stealth................... 30 Tech (Crafts)................ 30 Will.................... 31 Earth’s Secret History 33 Veilfall................... 33 Supernatural Immigration........... 35 The Cerulean Amendment.......... 36 Lifting the Veil................ 36 Organizations and NPCs 39 -

Introduction P. 5. Chapter One 1.1 Gothic Literature. P

INDEX Introduction P. 5. Chapter one 1.1 Gothic Literature. P. 8. 1.2 The Origin of Vampires. P. 15. Chapter two 2.1 John William Polidori’s “The Vampyre”. P. 34. 2.2 Théophile Gautier’s “La Morte Amoureuse”. P. 51. 2.3 Joseph Thomas Sheridan Le Fanu’s “Carmilla”. P. 66. Chapter three 3.1 Dracula’s Birth. P. 83. 3.2 The Real Dracula. P. 90. 3 3.3 The Plot. P. 93. 3.4 Blood and Class Struggle. P. 97. 3.5 Dracula and Women. P. 100. Conclusions P. 107. Appendix P. 110. Bibliography P. 132. 4 INTRODUCTION This work aims at describing how the figure of the vampire has changed during the nineteenth century, a period that saw a florid proliferation of novels about vampires. In the first chapter I focus briefly on the concept of Gothic literature whose birth is related, according to the majority of critics, to the publication of Horace Walpole’s Castle of Otranto, a short story about a ghost who hunts a castle. In the second part of the chapter, I deal with the figure of the vampire from a non-fictional point of view. This mythological creature, indeed, did not appear for the first time in novels, but its existence is attested already long time before the nineteenth century. The first document known about vampires dates back to the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, during the Byzantine empire, but the official documents that affirm the existence of these creatures come in succession for the following centuries too. The chapter presents some examples of these evidences such as Antonio de Ferrariis’s De situ Iapygiae, Joseph Pitton de Tournefort’s Relation d’un voyage au Levant, Dom Augustin Calmet’s Treatise on the Vampires of Hungary and Surrounding Regions. -

Turkic Mythology - the Origin of the Turks

Turkic Mythology - The Origin of the Turks The Turks entered in world history in 552 when the first Turkish Empire was founded. This state started Turkish history in the pre Islamic period, which lasted until the tenth century. The first Turkish state ended in 630 at the end of its long-lasting raids and wars with China, and the second one started in 682 and ended in 744. The pre-Islamic Turkish political history continued with the establishment of the Uyghur Kaghanate in the East (744-840) and the Khazar Khanagate in the West (630-965). The legends of Turkish origin vary depending on the sources, documentations, various Turkic communities, and those who tell the myths. Almost all Turco-Mongolian legends refer to a wolf story, a mythic mountain, a valley and a cave, a female figure, and iron forging; the themes of hiding and re-emergence of the Turks. The Chinese sources tell the origin myths depending on a she-wolf ancestor. This myth tell about the Turks as the ancestors of a tribe which was part of Hsiung-nus, and called themselves as Ashina, who lost all the members of the clan against the enemies except one boy. The boy lost his feet, so the legend says the enemies left him free. A she-wolf found him, milked him and when the boy grew, mated with him. Upon return of the enemies to kill the boy, the she-wolf run to a cave secluded in the mountains, and gave birth to ten boys, each got married with women from out, and adopted a family name, one having the name of Ashina. -

The Folk Beliefs in Vampire-Like Supernatural Beings in the Ottoman

An Early Modern Horror Story: The Folk Beliefs in Vampire-like Supernatural Beings in the Ottoman Empire and the Consequent Responses in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries by Salim Fikret Kırgi Submitted to Central European University History Department In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Associate Prof. Tijana Krstić Second Reader: Prof. György E. Szönyi Budapest, Hungary 2017 CEU eTD Collection Statement of Copyright “Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author.” CEU eTD Collection i Abstract The thesis explores the emergence and development of vampire awareness in the Ottoman Empire in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries by focusing on the interactions between religious communities, regional dynamics, and dominant discourses in the period. It re-evaluates the scattered sources on Ottoman approaches to the ‘folkloric vampire’ by taking the phenomenon as an early modern regional belief widespread in the Balkans, Central Europe and the Black Sea regions. In doing so, it aims to illuminate fundamental points, such as the definition of the folkloric revenant in the eyes of the Ottoman authorities in relation to their probable inspiration—Orthodox Christian beliefs and practices—as well as some reference points in the Islamic tradition. -

Slavic Pagan World

Slavic Pagan World 1 Slavic Pagan World Compilation by Garry Green Welcome to Slavic Pagan World: Slavic Pagan Beliefs, Gods, Myths, Recipes, Magic, Spells, Divinations, Remedies, Songs. 2 Table of Content Slavic Pagan Beliefs 5 Slavic neighbors. 5 Dualism & The Origins of Slavic Belief 6 The Elements 6 Totems 7 Creation Myths 8 The World Tree. 10 Origin of Witchcraft - a story 11 Slavic pagan calendar and festivals 11 A small dictionary of slavic pagan gods & goddesses 15 Slavic Ritual Recipes 20 An Ancient Slavic Herbal 23 Slavic Magick & Folk Medicine 29 Divinations 34 Remedies 39 Slavic Pagan Holidays 45 Slavic Gods & Goddesses 58 Slavic Pagan Songs 82 Organised pagan cult in Kievan Rus' 89 Introduction 89 Selected deities and concepts in slavic religion 92 Personification and anthropomorphisation 108 "Core" concepts and gods in slavonic cosmology 110 3 Evolution of the eastern slavic beliefs 111 Foreign influence on slavic religion 112 Conclusion 119 Pagan ages in Poland 120 Polish Supernatural Spirits 120 Polish Folk Magic 125 Polish Pagan Pantheon 131 4 Slavic Pagan Beliefs The Slavic peoples are not a "race". Like the Romance and Germanic peoples, they are related by area and culture, not so much by blood. Today there are thirteen different Slavic groups divided into three blocs, Eastern, Southern and Western. These include the Russians, Poles, Czechs, Ukrainians, Byelorussians, Serbians,Croatians, Macedonians, Slovenians, Bulgarians, Kashubians, Albanians and Slovakians. Although the Lithuanians, Estonians and Latvians are of Baltic tribes, we are including some of their customs as they are similar to those of their Slavic neighbors. Slavic Runes were called "Runitsa", "Cherty y Rezy" ("Strokes and Cuts") and later, "Vlesovitsa". -

C2> Hat C3£Oly Might in Bethlehem

■l mj.w*; - ‘ T- .-■ *• •*" ’ - "• '‘7”' ^ r*■ -^*-~v-b.mij , m *•v r41 SIXTY-FIRST YEAR CHATSWORTH. ILLINOIS, THURSDAY. DECEMBER 20. 1934 NO. IS R. R. KIRKTON CO-OPERATION C2> hat c3£oly Might i n B e t h l e h e m AGAIN HEADS BRINGS MORE FARN6UREAU GRAVEL ROADS H O T SLUGS EDIGRAPHS A Crowd of 2500 Attends Government Pays Men for Annual Meeting Held A nickel isn't supposed to Half of the world is en Labor and Township be as good as a dollar but it gaged In agriculture. That’s at Pontiac. goes to church oftener. how the other half lives. Buys Gravel. Some motorists consider It The scientist tells us that (Pontiac Dally Leader) good driving if they get R. R. Klrkton, well known red will overcome timidity. Highway Commissioner Andrew across fifty feet ahead of the This Is aso true of the long Eby has put in a busy summer im farmer of Waldo township, was tra in . re-elected president of the Living green. proving Chatsworth township One reason why business I highways and if weather condi ston County Farm Bureau at the But If Japan gets a fleet doesn’t pick up is because so tion will hold out a few days twenty-first annual meeting held equal to ours, she’ll soon be few are trying to pick up more he says every farmer in the in the gymnasium at Pontiac demanding equal rights to business. j township, save Raymond Stadler, township high school Tuesday. meddle, too. F*ully 2,500 farmers and mem in the southeast corner of the bers of their families attended. -

January/February 2007 Inside

Bringing history into accord with the facts in the tradition of Dr. Harry Elmer Barnes The Barnes Review A JOURNAL OF NATIONALIST THOUGHT & HISTORY VOLUME XIII NUMBER 1 JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2007 www.barnesreview.org The Amazing Baltic Origins of Homer’s Epics A Christmas Day Civil War Atrocity: The Wilson Massacre Japan’s Emperor Komei Killed by Rothschild Agents The Nazis & Pearl Harbor: Was the Luftwaffe Involved? Exposing the Judas Goats: The Enemy Within vs. American Nationalists ALSO: • Gen. Leon Degrelle • September 11 Foul Ups Psychopaths in History: • Founding Myths • The Relevance of Christianity Who are they? Do you have one next door? • Much more . Bringing History Into Accord With the Facts in the Tradition of Dr. Harry Elmer Barnes the Barnes Review AJOURNAL OF NATIONALIST THOUGHT &HISTORY JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2007 O VOLUME XIII O NUMBER 1 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS BALTIC ORIGIN OF HOMER’S TALES EXPERIENCES WITH AN ADL AGENT 4 JOHN TIFFANY 40 MICHAEL COLLINS PIPER The tall tales of the still universally read storyteller Homer A Judas Goat is an animal trained to lead others to the involve ancient Greeks, so we naturally assume (as do slaughterhouse. A human “Judas Goat” performs the same almost all scholars) any events related to them must have function in an allegorical way. Typical of this human breed taken place in the Mediter ranean. But we tend to forget of “Judas Goat” was an ADL agent the author knew per- the Greeks originally came from somewhere else, some- sonally, and liked. Roy Bullock was charming, skilled and where to the north. -

Tengrianstvo As National and State and National Religion of the Turko-Mongolian People of Internal Asia

TENGRIANSTVO AS NATIONAL AND STATE AND NATIONAL RELIGION OF THE TURKO-MONGOLIAN PEOPLE OF INTERNAL ASIA ТЭНГРИАНСТВО КАК НАЦИОНАЛЬНАЯ И ГОСУДАРСТВЕННАЯ РЕЛИГИЯ ТЮРКО-МОНГОЛОВ ЦЕНТРАЛЬНОЙ АЗИИ ORTA ASYA TÜRK-MOGOLLARDA RESMİ VE MİLLİ DİN OLARAK TENGRİZM * Nikolai ABAEV ABSTRACT The article deals with the synenergetic role of Tengrian religion, influence of the ideology of “tengrism” on the processes of politogenesis of the Turkic-Mongolian people’s as well as the evolution of the imperial forms of statehood of the Hunnu (the Hunnu Empire) and the Great Mongolian Empire (Khamag Mongol Uls). It shows the role of tengrism in the process of social organization and self-organization in the nomadic civilization of the Turkic-Mongolian peoples of Central Asia. Keywords: ideology of tengrism, “Tengrianstvo”, processes of social self- organisation, structurogenesis, the Statehood, Empire of Hunnu, Hamag Mongol Uls. АННОТАЦИЯ В данной статье рассматривается синергетическая роль тэнгрианской религии, влияние идеологии «тэнгризма» на процессы политогенеза тюрко-монгольских народов, а также на становление имперских форм государственности, в том числе на формирование государственности хунну (Империя Хунну) и Великой Монгольской Империи (Хамаг Монгол Улс), показана роль тэнгрианства в процессах социальной организации и самоорганизации в кочевнической цивилизации тюрко-монгольских народов Центральной Азии. Ключевые слова: религия, идеология, тэнгрианская религия, синергетика, процесс социальной самоорганизации, самоорганизация, государственность, Империя Хунну, Хамаг Монгол Улс. * PhD, Professor, Head of Laboratory of civilizational geopolitics of Institute of Inner Asia of BSU ÖZET Makalede Tengrizm’in sinerjik rolü, Tengrizm ideolojinin Türk-Mogol Halklarda siyası yaradılış sürecine, Hunnu İmparatorluğu ile Büyük Mogol İmparatorluğun kurulmasında, genel anlamda imparatorlukların kuruluşunda etken olduğu tetkik edilmiştir. Orta Asya Göçebe Halkların hayat ve düzeninde Tengrizm’in rolü gösterilmiştir. -

PROBLEMS of ACCULTURATION in TURKISH-SLAVIC RELATIONS and THEIR REFLECTION in the “HEAVEN and EARTH” MYTHOLOGEME Abay K

PJAEE, 17 (6) (2020) PROBLEMS OF ACCULTURATION IN TURKISH-SLAVIC RELATIONS AND THEIR REFLECTION IN THE “HEAVEN AND EARTH” MYTHOLOGEME Abay K. KAIRZHANOV1 1Department of Turkology, L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian National L. N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University 010000, 2 Satbayev Str., Astana, Republic of Kazakhstan [email protected] Nazira NURTAZINA2 2Department of the History of Kazakhstan Al Farabi Kazakh National University, 020000, Almaty, Republic of Kazakhstan [email protected] Aiman M. AZMUKHANOVA3 3Department of Oriental Studies L. N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University 010000, 2 Satbayev Str., Astana, Republic of Kazakhstan [email protected] Kuanyshbek MALIKOV4 4Department of Kazakh Linguiatics L. N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University 010000, 2 Satbayev Str., Astana, Republic of Kazakhstan Karlygash K. SAREKENOVA5 5Department of Kazakh Linguiatics L. N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University 010000, 2 Satbayev Str., Astana, Republic of Kazakhstan [email protected] Abay K. KAIRZHANOV1, Nazira NURTAZINA2, Aiman M. AZMUKHANOVA3, Kuanyshbek MALIKOV4, Karlygash K. SAREKENOVA5 – Palarch’s Journal Of Archaeology Of Egypt/Egyptology 17(6). ISSN 1567-214x Key words: acculturation, functional unity, new balance, mythologeme, dualistic system. -- Annotation The relevance of the study in this article is determined by the fact that long and constant contacts between the ancient Turks and Slavs formed significant cultural components in the 6936 PJAEE, 17 (6) (2020) context of communication between peoples. In the interaction of carriers of culture not only a certain shift of cultural paradigms take place, but also ethnic groups enter into complex relationships, while in the process of acculturation of each of them finds its identity and specificity, are mutually adapted by borrowing some of the cultural traits of each other. -

Otherness and Intertextuality in the Witcher. the Duality of Experiencing

Anna Michalska 6875769 Otherness and Intertextuality in The Witcher. The Duality of Experiencing Andrzej Sapkowski’s Universe Utrecht University Literature Today: English and Comparative Literature Supervisor: Frank Brandsma Second evaluator: Jeroen Salman July 2020, Utrecht Michalska 2 Table of Contents Abstract................................................................................................................. 4 Introduction..........................................................................................................5 I. A Hero, an Anti-hero, a No-hero. The Witcher As a Misfit.......................14 Misfit, or Description of a Witcher..........................................15 Literary Background..................................................................16 Hero, or Description of Geralt.................................................19 Monstrum, or Description of a Witcher.................................23 The Professional, or Description of Geralt............................26 II. Slavic-ness and Intertextuality in The Witcher..........................................30 Cultural Background: The Mythology Which Is Not.............31 Literary Background: Polish Ghosts of The Past..................32 The Witcher’s Slavic Demonology, Legends and Customs..35 Author’s View: Trifling Slavic-ness..........................................37 Western Fairy Tales vs Anti-Fairy Tales..................................39 The Implied Author, the Storyteller, the Erudite. Three Levels of Reading.......................................................................44