FWS/R4/ES August 8, 2006 Mr. David Paulison, Director Federal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Monroe County Comprehensive Plan Addresses the Data Inventory Requirements of 9J‐5.0005 (2) of the Florida Administrative Code (F.A.C.)

Monroe County Comprehensive Plan Update HOUSING Table of Contents Item Page 7.0 HOUSING ELEMENT.................................................................................................................................... 1 7.1 Introduction..................................................................................................................................... 1 7.1.1 Policy Framework........................................................................................................... 1 7.1.2 Residential Land Use Characteristics...................................................................11 7.2 Existing Housing Stock Characteristics..............................................................................12 7.2.1 Type of Housing ............................................................................................................12 7.2.2 Occupancy and Tenure ..............................................................................................14 7.2.3 Vacancy Status ...............................................................................................................16 7.2.4 Age of Housing ..............................................................................................................18 7.2.5 Price/Rent Characteristics and Affordability ..................................................19 7.2.6 Cost to Income Ratios ................................................................................................29 7.2.7 Structural Conditions of Housing Stock .............................................................31 -

East Coast.Xlsx

Bagster® collection service is available in the following areas. This list is alphabetical by state and then by city name. Please note that some zip codes within a city may not be serviced due to local franchise restrictions. Bagster collection service area subject to change at any time. If your area is not listed or you have questions visit www.thebagster.com or call 1-877-789-BAGS (2247). State City Zip CT A A R P Pharmacy 06167 CT Abington 06230 CT Accr A Data 06087 CT Advertising Distr Co 06537 CT Advertising Distr Co 06538 CT Aetna Insurance 06160 CT Aetna Life 06156 CT Allingtown 06516 CT Allstate 06153 CT Amston 06231 CT Andover 06232 CT Ansonia 06401 CT Ansonia 06418 CT Ashford 06250 CT Ashford 06278 CT Avon 06001 CT Bakersville 06057 CT Ballouville 06233 CT Baltic 06330 CT Baltic 06351 CT Bank Of America 06150 CT Bank Of America 06151 CT Bank Of America 06180 CT Bantam 06750 CT Bantam 06759 CT Barkhamsted 06063 CT Barry Square 06114 CT Beacon Falls 06403 CT Belle Haven 06830 CT Berlin 06037 CT Bethany 06524 CT Bethel 06801 CT Bethlehem Village 06751 CT Bishop's Corner 06117 CT Bishop's Corner 06137 CT Bissell 06074 CT Bloomfield 06002 CT Bloomingdales By Mail Ltd 06411 CT Blue Hills 06002 CT Blue Hills 06112 CT Bolton 06043 CT Borough 06340 CT Botsford 06404 CT Bozrah 06334 CT Bradley International Airpor 06096 CT Branford 06405 CT Bridgeport 06601 CT Bridgeport 06602 CT Bridgeport 06604 CT Bridgeport 06605 CT Bridgeport 06606 CT Bridgeport 06607 CT Bridgeport 06608 CT Bridgeport 06610 CT Bridgeport 06611 CT Bridgeport 06612 -

October 24, 2018 Meeting Minutes

PLANNING COMMISSION October 24, 2018 Meeting Minutes The Planning Commission of Monroe County conducted a meeting on Wednesday, October 24, 2018, beginning at 10:00 a.m. at the Marathon Government Center, 2798 Overseas Highway, Marathon, Florida. CALL TO ORDER PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE ROLL CALL by Debra Roberts PLANNING COMMISSION MEMBERS Denise Werling, Chair Present William Wiatt Present Ron Miller Present Kristen Livengood Present Tom Coward Present STAFF Emily Schemper, Acting Sr. Director of Planning and Environmental Resources Present Steve Williams, Assistant County Attorney Present John Wolfe, Planning Commission Counsel Present Cheryl Cioffari, Comprehensive Planning Manager Present Bradley Stein, Planning and Development Review Manager Present Debra Roberts, Planning Coordinator Present Deborah Griffin, Assistant Present COUNTY RESOLUTION 131-92 APPELLANT TO PROVIDE RECORD FOR APPEAL County Resolution 131-92 was read into the record by Mr. Wolfe. SUBMISSION OF PROPERTY POSTING AFFIDAVITS AND PHOTOGRAPHS Ms. Debra Roberts confirmed receipt of all necessary paperwork. SWEARING OF COUNTY STAFF County staff members were sworn in by Mr. Wolfe. CHANGES TO THE AGENDA Ms. Emily Schemper requested that Items 7 and 8 be heard first, and that Items 5 and 6 be read together. 1 APPROVAL OF MINUTES Motion: Commissioner Livengood made a motion to approve the September 26, 2018, meeting minutes. Commissioner Wiatt seconded the motion. There was no opposition. The motion passed unanimously. MEETING 7. WASTE MANAGEMENT OF FLORIDA, INC. WASTE TRANSFER STATION, 143 TOPPINO INDUSTRIAL DRIVE, ROCKLAND KEY, MILE MARKER 9 BAY SIDE: A PUBLIC HEARING CONCERNING A REQUEST FOR A MAJOR CONDITIONAL USE PERMIT FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF A PROPOSED WASTE TRANSFER STATION. -

July 30, 2014 Meeting Minutes

PLANNING COMMISSION July 30, 2014 Meeting Minutes The Planning Commission of Monroe County conducted a meeting on Wednesday, July 30, 2014, beginning at 10:00 a.m. at the Marathon Government Center, 2798 Overseas Highway, Marathon, Florida. CALL TO ORDER PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE ROLL CALL by Gail Creech PLANNING COMMISSION MEMBERS William Wiatt, Chair Present Jeb Hale, Vice Chair Present Elizabeth Lustberg Present Ron Miller Present Denise Werling Present STAFF Townsley Schwab, Senior Director of Planning and Environmental Resources Present Susan Grimsley, Assistant County Attorney Present Steve Williams, Assistant County Attorney Present Joe Haberman, Planning & Development Review Manager Present Mitch Harvey, Comp Plan Manager Present Mike Roberts, Sr. Administrator, Environmental Resources Present Karl Bursa, Planner Present Gail Creech, Planning Commission Coordinator Present Mr. Williams informed the Commissioners that any advice rendered by himself today will be on behalf of the County and staff and that the Commission is essentially operating today without the assistance of their own counsel. COUNTY RESOLUTION 131-91 APPELLANT TO PROVIDE RECORD FOR APPEAL County Resolution 131-92 was read into the record by Mr. Williams. SUBMISSION OF PROPERTY POSTING AFFIDAVITS AND PHOTOGRAPHS Gail Creech confirmed receipt of all necessary paperwork. SWEARING OF COUNTY STAFF County staff members were sworn in by Ms. Grimsley. 1 CHANGES TO THE AGENDA Ms. Creech stated that the applicant for Item 1 has requested to continue the matter to August 27, 2014. There were some posting issues with Item 3 and that item will not be heard at today’s meeting. APPROVAL OF MINUTES Motion: Commissioner Lustberg made a motion to approve the minutes of the June 25, 2014 meeting. -

Survey of State-Listed Reptiles in the Florida Keys

Survey of State-listed Reptiles in the Florida Keys FINAL REPORT Jonathan D. Mays and Kevin M. Enge October 31, 2016 Reptile and Amphibian Subsection Fish and Wildlife Research Institute Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission 1105 SW Williston Rd. Gainesville, FL 32601 FINAL REPORT Reptile and Amphibian Subsection Wildlife Research Section Fish and Wildlife Research Institute Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Project Title: Survey of State-listed Reptiles in the Florida Keys Project Number: 9241-295-1313 Project Duration: July 2015 to October 2016 Principal Investigators: Jonathan Mays and Kevin Enge, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, FWRI, Wildlife Research Section, Reptile and Amphibian Subsection, 1105 S.W. Williston Road, Gainesville, FL 32601 Cooperators: Adam Emerick (USFWS), Pierson Hill (FWC-FWRI), Kenneth Krysko (FLMNH), Ricardo Zambrano and Carol Rizkalla (FWC- HSC), Prepared By: Jonathan Mays and Kevin Enge Date Submitted: 31 October 2016 Survey of State-listed Reptiles in the Florida Keys 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 6 Environment ................................................................................................................................ 6 Target Reptile Taxa ..................................................................................................................... 7 Objectives .................................................................................................................................. -

Fema-Administration-Of-National-Flood

complaint in 2003, the plaintiffs filed suit against FEMA and the Service pursuant to the Act and the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) (79 Stat. 404; 5 U.S.C. 500 et seq.). The plaintiffs won a Summary Judgment on all three counts of their complaint. On March 29, 2005, the United States District Court, Southern District of Florida (Court) issued an Order ruling the Service and FEMA violated the Act and the APA. Specifically, the Court found: (1) the Service and FEMA violated the Act’s section 7(a)(2) and APA’s prohibition against actions that are arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, or otherwise not in accordance with the law by failing to protect against jeopardy; (2) the Service and FEMA failed to ensure against adverse modification of critical habitat for the endangered silver rice rat; and (3) FEMA failed to develop and implement a conservation program for listed species under section 7(a)(1) of the Act. On September 9, 2005, the Court granted the plaintiffs’ motion for an injunction against FEMA issuing flood insurance on any new residential or commercial developments in suitable habitats of federally listed species in the Keys. The injunction applied to properties on a list of potential suitable habitat submitted to the Court by the Service. Plaintiffs have stipulated to the removal of some properties on the suitable habitat list based on Plaintiffs’ determination that the properties were not located in suitable habitat, thereby enabling some owners to obtain flood insurance. The Court also ordered the Service to submit a new BO by August 9, 2006. -

August 21, 2018

DEVELOPMENT REVIEW COMMITTEE Tuesday, August 21, 2018 MEETING MINUTES The Monroe County Development Review Committee conducted a meeting on Tuesday, August 21, 2018, beginning at 1:00 p.m. at the Marathon Government Center, Media & Conference Room (1st floor, rear hallway), 2798 Overseas Highway, Marathon, Florida. CALL TO ORDER by Emily Schemper ROLL CALL by Debra Roberts DRC MEMBERS Emily Schemper, Assistant Director of Planning and Environmental Resources Present Mike Roberts, Sr. Administrator, Environmental Resources Absent STAFF MEMBERS Steve Williams, Assistant County Attorney Absent Peter Morris, Assistant County Attorney Absent Bradley Stein, Development Review Manager Present Cheryl Cioffari, Comprehensive Planning Manager Present Debra Roberts, Administrative Assistant Present CHANGES TO THE AGENDA There were no changes to the agenda. MINUTES FOR APPROVAL Approval of the meeting minutes for Tuesday, July 25, 2018. MEETING 1. Waste Management of Florida, Inc. Waste Transfer Station, 143 Toppino Industrial Drive, Rockland Key, Mile Marker 9 Bay Side: A public meeting concerning a request for a Major Conditional Use Permit for the Development of a proposed Waste Transfer Station. The subject property is described as a Parcel of Land in Part of Government Lots 5, 6 and 7, Section 21, Township 67 South, Range 26 East, Rockland Key, Monroe County, Florida, having Real Estate Numbers 00122070-000300, 00122080-000101 and 00122080-000301. (File #2018-106) Mr. Bradley Stein, Development Review Manager, presented the staff report. This is a request for a Major Conditional Use Permit from Waste Management, Inc. of Florida, located at 143 Toppino Industrial Drive, Rockland Key, Mile Marker 9. The majority of this site plan has already been approved as a permitted use on the site in Industrial Zoning. -

Florida Keys Mile-Marker Guide

Road Trip: Florida Keys Mile-Marker Guide Overseas Highway, mile by mile: Plan your Florida Keys itinerary The Overseas Highway through the Florida Keys is the ultimate road trip: Spectacular views and things to do, places to go and places to hide, hidden harbors and funky tiki bars. There are hundreds of places to pull over to fish or kayak or enjoy a cocktail at sunset. There are dozens of colorful coral reefs to snorkel or dive. Fresh seafood is a Florida Keys staple, offered at roadside fish shacks and upscale eateries. For many, the destination is Key West, at the end of the road, but you’ll find the true character of the Florida Keys before you get there. This mile-marker guide will help you discover new things to see and do in the Florida Keys. It’s a great tool for planning your Florida Keys driving itinerary. Card Sound Road 127.5 — Florida City – Junction with Fla. Turnpike and U.S. 1. 126.5 — Card Sound Road (CR-905) goes east to the Card Sound Bridge and northern Key Largo. If you’re not in a hurry, take the toll road ($1 toll). Card Sound Road traverses a wild area that once had a small community of Card Sound. All that’s left now is Alabama Jack’s, a funky outdoor restaurant and tiki bar known for its conch fritters and the line of motorcycles it attracts. (Don’t be afraid; it’s a family oriented place and great fun.) If you take Card Sound Road, you’ll pass a little-known park, Dagny Johnson Key Largo Hammock Botanical State Park, before coming to Key Largo itself. -

Implementing NTHMP-MMS Strategic Plan in Tsunami Hazard Mitigation

NOAA Project Report Development of Four Additional Tsunami Inundation Maps with Revision of Port Aransas, TX and Updating Existing Ones with Maritime Products Final Report to the National Tsunami Hazard Mitigation Program (NTHMP) in Completion of Project Awards NA15NWS4670031 and NA16NWS4670039 Authors Juan J Horrillo Texas A&M University at Galveston Wei Cheng Jens Figlus Collaborators: Chayne Sparagowski Coastal Bend Council of Governments NTHMP Mitigation and Education Subcommittee Under the guidance of NTHMP Mapping and Modeling Subcommittee National Tsunami Hazard Mitigation National Oceanic and Atmospheric Program Administration Ocean Engineering Texas A&M University at Galveston Galveston, Texas, 77553 November 2017 Contents 1 Executive Summary . 1 1 Introduction . 2 1.1 Background . 2 1.2 Regional and Historical Context . 6 2 Tsunami Inundation Modeling . 9 2.1 Landslide Tsunami Sources . 9 2.2 Numerical Models . 9 3 Tsunami Maps . 11 3.1 Pensacola, FL . 11 3.2 Key West, FL . 27 3.3 Okaloosa County, FL . 44 3.4 Santa Rosa County, FL . 77 3.5 Mustang Island, TX . 110 4 Tsunami and Hurricane Storm Surge Inundation . 143 4.1 Pensacola, FL . 145 4.2 Key West, FL . 148 4.3 Okaloosa County, FL . 151 4.4 Santa Rosa County, FL . 156 4.5 Mustang Island, TX . 161 5 Tsunami Maritime Products . 166 5.1 South Padre Island, TX . 169 5.2 Mustang Island, TX . 173 5.3 Mobile, AL . 180 5.4 Pensacola, FL . 187 5.5 Santa Rosa County, FL . 192 5.6 Okaloosa County, FL . 199 5.7 Panama City, FL . 206 5.8 Tampa, FL . 211 5.9 Key West, FL . -

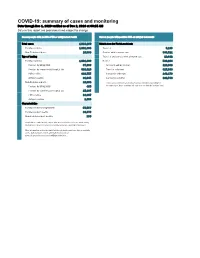

COVID-19: Summary of Cases and Monitoring Data Through Dec 1, 2020 Verified As of Dec 2, 2020 at 09:25 AM Data in This Report Are Provisional and Subject to Change

COVID-19: summary of cases and monitoring Data through Dec 1, 2020 verified as of Dec 2, 2020 at 09:25 AM Data in this report are provisional and subject to change. Cases: people with positive PCR or antigen test result Cases: people with positive PCR or antigen test result Total cases 1,018,160 Risk factors for Florida residents 1,001,800 Florida residents 1,001,800 Traveled 9,183 Non-Florida residents 16,360 Contact with a known case 383,521 Type of testing Traveled and contact with a known case 10,892 Florida residents 1,001,800 Neither 598,204 Positive by BPHL/CDC 37,986 No travel and no contact 129,666 Positive by commercial/hospital lab 963,814 Travel is unknown 327,338 PCR positive 910,755 Contact is unknown 246,179 Antigen positive 91,045 Contact is pending 192,746 Non-Florida residents 16,360 Travel can be unknown and contact can be unknown or pending for Positive by BPHL/CDC 465 the same case, these numbers will sum to more than the "neither" total. Positive by commercial/hospital lab 15,895 PCR positive 13,397 Antigen positive 2,963 Characteristics Florida residents hospitalized 55,567 Florida resident deaths 18,776 Non-Florida resident deaths 236 Hospitalized counts include anyone who was hospitalized at some point during their illness. It does not reflect the number of people currently hospitalized. More information on deaths identified through death certificate data is available on the National Center for Health Statistics website at www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/COVID19/index.htm. -

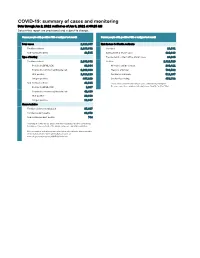

COVID-19: Summary of Cases and Monitoring Data Through Jun 2, 2021 Verified As of Jun 3, 2021 at 09:25 AM Data in This Report Are Provisional and Subject to Change

COVID-19: summary of cases and monitoring Data through Jun 2, 2021 verified as of Jun 3, 2021 at 09:25 AM Data in this report are provisional and subject to change. Cases: people with positive PCR or antigen test result Cases: people with positive PCR or antigen test result Total cases 2,329,867 Risk factors for Florida residents 2,286,332 Florida residents 2,286,332 Traveled 18,931 Non-Florida residents 43,535 Contact with a known case 920,896 Type of testing Traveled and contact with a known case 24,985 Florida residents 2,286,332 Neither 1,321,520 Positive by BPHL/CDC 83,364 No travel and no contact 280,411 Positive by commercial/hospital lab 2,202,968 Travel is unknown 733,532 PCR positive 1,819,119 Contact is unknown 511,267 Antigen positive 467,213 Contact is pending 459,732 Non-Florida residents 43,535 Travel can be unknown and contact can be unknown or pending for Positive by BPHL/CDC 1,037 the same case, these numbers will sum to more than the "neither" total. Positive by commercial/hospital lab 42,498 PCR positive 29,688 Antigen positive 13,847 Characteristics Florida residents hospitalized 95,607 Florida resident deaths 36,973 Non-Florida resident deaths 744 Hospitalized counts include anyone who was hospitalized at some point during their illness. It does not reflect the number of people currently hospitalized. More information on deaths identified through death certificate data is available on the National Center for Health Statistics website at www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/COVID19/index.htm. -

Taxonomy Versus Phylogeny Phylogeography of Marsh Rabbits Without Hopping to Conclusions

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2010 Taxonomy Versus Phylogeny Phylogeography Of Marsh Rabbits Without Hopping To Conclusions Rosanna M. Tursi University of Central Florida Part of the Biology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Tursi, Rosanna M., "Taxonomy Versus Phylogeny Phylogeography Of Marsh Rabbits Without Hopping To Conclusions" (2010). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 1690. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/1690 TAXONOMY VERSUS PHYLOGENY: PHYLOGEOGRAPHY OF MARSH RABBITS WITHOUT HOPPING TO CONCLUSIONS by ROSANNA M. TURSI B.S. Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, FL, 2006 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the Department of Biology in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2010 Major Professor: Eric A. Hoffman © 2010 Rosanna M. Tursi ii ABSTRACT Subspecific taxonomic designations solely based on morphological characters can often lead to erroneous assumptions about the evolutionary history of populations. This study sought to investigate evolutionary questions and conservation implications associated with morphological subspecific designations of island populations. To this end, I focused my attention on the Lower Keys of Florida, a unique chain of islands with well-known geologic history and rich in endemic, endangered subspecies.