Patient Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baseline Vitals &

Baseline Vitals and Sample History Company Drill Instructor Guide Session Reference: 1 Topic: Baseline Vitals and Sample History Company Drill Level of Instruction: 2 Time Required: Three Hours Materials Blood Pressure cuff & stethoscope Pen light Clock or wrist watch with second hand Writing paper Writing pencil Personal protective equipment: gloves References Brady Emergency Care, 11th Edition, The Maryland Medical Protocols for Emergency Medical Services Providers, Effective July 1, 2011, Maryland Institute for Emergency Medical Services Systems Preparation Motivation The Baseline Vitals and SAMPLE History are part of the essential information necessary to obtain and document in order to give a patient the best possible care in the field. This information can alert the provider to call for additional resources if necessary and can give those accepting care of the patient at the next level of patient care a good idea of what may be going on inside the patient’s body. Objective (SPO) 1-1: Given a live victim; blood pressure cuff; stethoscope; pencil; paper; pen light; clock or wrist watch, the student will be able to demonstrate, from memory and without assistance, the proper procedures in obtaining a set of Baseline Vitals, to include: pulse, respirations, skin color, skin temperature and condition, pupil appearance, blood pressure and be able to document the same at a practical station, as governed by The Maryland Medical Protocols for Emergency Medical Services Providers, Effective January 1, 2002 and the Brady Emergency Care, 7th Edition, EMT-Basic National Standard Curriculum. The student will also be able to score a 70% or above on a written exam. -

ABCDE Approach

The ABCDE and SAMPLE History Approach Basic Emergency Care Course Objectives • List the hazards that must be considered when approaching an ill or injured person • List the elements to approaching an ill or injured person safely • List the components of the systematic ABCDE approach to emergency patients • Assess an airway • Explain when to use airway devices • Explain when advanced airway management is needed • Assess breathing • Explain when to assist breathing • Assess fluid status (circulation) • Provide appropriate fluid resuscitation • Describe the critical ABCDE actions • List the elements of a SAMPLE history • Perform a relevant SAMPLE history. Essential skills • Assessing ABCDE • Needle-decompression for tension • Cervical spine immobilization pneumothorax • • Full spine immobilization Three-sided dressing for chest wound • • Head-tilt and chin-life/jaw thrust Intravenous (IV) line placement • • Airway suctioning IV fluid resuscitation • • Management of choking Direct pressure/ deep wound packing for haemorrhage control • Recovery position • Tourniquet for haemorrhage control • Nasopharyngeal (NPA) and oropharyngeal • airway (OPA) placement Pelvic binding • • Bag-valve-mask ventilation Wound management • • Skin pinch test Fracture immobilization • • AVPU (alert, voice, pain, unresponsive) Snake bite management assessment • Glucose administration Why the ABCDE approach? • Approach every patient in a systematic way • Recognize life-threatening conditions early • DO most critical interventions first - fix problems before moving on -

Clinical Handbook Health Care for Children Subjected to Violence Or Sexual Abuse

KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA NATION RELIGION KING MINISTRY OF HEALTH CLINICAL HANDBOOK HEALTH CARE FOR CHILDREN SUBJECTED TO VIOLENCE OR SEXUAL ABUSE 2017 PREFACE Violence against children is a serious public health concern and a human rights violation with consequences that impact their lives in various ways. Violence and sexual abuse suffered in childhood adversely affects the body as well as the mind, which can lead to a broad range of behavioral, psychological and physical problems that persist into adulthood. Healthcare practitioners play a significantly important role in prevention and response to violence against children. They are often the first or only point of reference for children who have experienced violence, detecting abuse and providing immediate and longer-term care and support to children and families. In 2015, the Ministry of Health developed “the National Guidelines for Management of Violence Against Women and Children in the Health Sector”, which provides health care centers and referral hospitals with an overview of prevention and response in the health sector to violence against women and children. This “Clinical Handbook on Health Care for Children Subjected to Violence or Sexual Abuse” elaborates on knowledge and skills required to implement the National Guidelines. It aims to serve as a guide to ensure a prompt and adequate response to child victims of violence or sexual abuse for all healthcare practitioners. It provides further guidance on first line support, medical treatment, psychosocial support, and referral to key social and legal protection services. It can be also used as a resource manual for capacity development and training. Phnom Penh, 30th January 2017 Prof. -

Vital Signs and SAMPLE History

CHAPTER 9 Vital Signs and SAMPLE History Limmer et al., Emergency Care Update, 10th Edition © 2007 by Pearson Education, Inc. Upper Saddle River, NJ Overall Assessment Scheme Scene SizeSize--UpUp Initial Assessment Trauma Medical Physical Exam SAMPLE History Vital Signs & Physical Exam SAMPLE History & Vital Signs HOSP Detailed Ongoing Physical Exam Assessment Limmer et al., Emergency Care Update, 10th Edition © 2007 by Pearson Education, Inc. Upper Saddle River, NJ Baseline Vital Signs Limmer et al., Emergency Care Update, 10th Edition © 2007 by Pearson Education, Inc. Upper Saddle River, NJ Baseline Vital Signs Pulse Respirations Skin Pupils Blood Pressure Limmer et al., Emergency Care Update, 10th Edition © 2007 by Pearson Education, Inc. Upper Saddle River, NJ Pulse Limmer et al., Emergency Care Update, 10th Edition © 2007 by Pearson Education, Inc. Upper Saddle River, NJ Pulse Rate Adults generally 60-100/minute. Tachycardia is pulse more than 100/minute. Bradycardia is pulse less than 60/minute. More than 120 or less than 50 may be a critical finding. Limmer et al., Emergency Care Update, 10th Edition © 2007 by Pearson Education, Inc. Upper Saddle River, NJ Pulse Quality Strong or weak Regular or irregular Limmer et al., Emergency Care Update, 10th Edition © 2007 by Pearson Education, Inc. Upper Saddle River, NJ If you cannot feel a radial or brachial pulse, check the carotid pulse. Limmer et al., Emergency Care Update, 10th Edition © 2007 by Pearson Education, Inc. Upper Saddle River, NJ Respirations Limmer et al., Emergency Care Update, 10th Edition © 2007 by Pearson Education, Inc. Upper Saddle River, NJ Respiratory Quality Normal Shallow Labored Noisy Limmer et al., Emergency Care Update, 10th Edition © 2007 by Pearson Education, Inc. -

Emergency Medical Services Program Policies – Procedures – Protocols

Emergency Medical Services Program Policies – Procedures – Protocols Protocols Table of Contents GENERAL PROVISIONS ................................................................................................ 3 DESTINATION DECISION SUMMARY-METRO BAKERSFIELD AREA ........................ 5 DETERMINATION OF DEATH ..................................................................................... 12 101 AIRWAY OBSTRUCTION ...................................................................................... 16 102 ALTERED LEVEL OF CONSCIOUSNESS ............................................................ 18 103 ALLERGIC REACTION/ANAPHYLAXIS ................................................................ 20 104 ASYSTOLE/ PULSELESS ELECTRICAL ACTIVITY ............................................. 22 105 BITES STINGS ENVENOMATION ......................................................................... 24 106 BRADYCARDIA ..................................................................................................... 26 107 BRIEF RESOLVED UNEXPLAINED EVENT ......................................................... 29 108 BURNS ................................................................................................................... 32 109 CHEMPACK ........................................................................................................... 35 110 CHEST PAIN OR ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROME ........................................... 37 111 CHEST TRAUMA .................................................................................................. -

Wilderness First Aid Reference Cards

Pulse/Pressure Points Wilderness First Aid Reference Cards Carotid Brachial Prepared by: Andrea Andraschko, W-EMT Radial October 2006 Femoral Posterior Dorsalis Tibial Pedis Abdominal Quadrants Airway Anatomy (Looking at Patient) RIGHT UPPER: LEFT UPPER: ANTERIOR: ANTERIOR: GALL BLADDER STOMACH LIVER SPLEEN POSTERIOR: POSTERIOR: R. KIDNEY PANCREAS L. KIDNEY RIGHT LOWER: ANTERIOR: APPENDIX CENTRAL AORTA BLADDER Tenderness in a quadrant suggests potential injury to the organ indicated in the chart. Patient Assessment System SOAP Note Information (Focused Exam) Scene Size-up BLS Pt. Information Physical (head to toe) exam: DCAP-BTLS, MOI Respiratory MOI OPQRST • Major trauma • Air in and out Environmental conditions • Environmental • Adequate Position pt. found Normal Vitals • Medical Nervous Initial Px: ABCs, AVPU Pulse: 60-90 Safety/Danger • AVPU Initial Tx Respiration: 12-20, easy Skin: Pink, warm, dry • Move/rescue patient • Protect spine/C-collar SAMPLE LOC: alert and oriented • Body substance isolation Circulatory Symptoms • Remove from heat/cold exposure • Pulse Allergies Possible Px: Trauma, Environmental, Medical • Consider safety of rescuers • Check for and Stop Severe Bleeding Current Px Medications Resources Anticipated Px → Past/pertinent Hx • # Patients STOP THINK: Field Tx ast oral intake • # Trained rescuers A – Continue with detailed exam L S/Sx to monitor VPU EVAC NOW Event leading to incident • Available equipment (incl. Pt’s) – Evac level Patient Level of Consciousness (LOC) Shock Assessment Reliable Pt: AVPU Hypovolemic – Low fluid (Tank) Calm A+ Awake and Cooperative Cardiogenic – heart problem (Pump) Comment: Cooperative A- Awake and lethargic or combative Vascular – vessel problem (Hose) If a pulse drops but does not return Sober V+ Responds with sound to verbal to ‘normal’ (60-90 bpm) within 5-25 Alert stimuli Volume Shock (VS) early/compensated minutes, an elevated pulse is likely caused by VS and not ASR. -

Sample History and Physical Note for Gout

Sample History and Physical Note Charting Plus™ - Electronic Medical Records www.medinotes.com Note for Jane Doe on 2/27/04 - Chart 5407 Chief Complaint: This 31 year old female presents today with abdominal pain. Duration: Condition has existed for one month. Modifying Factors: Patient indicates lying down improves condition and standing worsens condition. Severity: The severity has worsened over the past 3 months. LMP: 4-05-2002. Allergies: Patient admits allergies to penicillin. Medication History: None. Past Medical History: Past medical history is unremarkable. Past Surgical History: Patient admits past surgical history of (+) cholecystectomy in 1998. Social History: Patient denies alcohol use. Patient denies illegal drug use. Patient denies STD history. Patient denies tobacco use. Family History: Patient admits a family history of cancer of breast associated with mother. Review of Systems: Cardiovascular: (-) cardiovascular problems or chest symptoms Constitutional Symptoms: (-) constitutional symptoms such as fever, headache, nausea, dizziness Genitourinary: (-) GU symptoms Physical Exam: BP Standing: 118/72 Resp: 18 HR: 68 Height: 5 ft. 7 in. Weight: 134 lbs. Patient is a 31 year old female who appears pleasant, in no apparent distress, her given age, well developed, well nourished and with good attention to hygiene and body habitus. Eyes: Conjunctiva and lids reveal no signs or symptoms of infection. Pupil exam reveals round and reactive pupils without afferent pupillary defect. Optic discs with normal color, contour and cupping bilaterally. Retinas are flat with normal vasculature out to the far periphery with no peripheral holes, breaks or tears observed. ENT: Gross hearing test reveals normal hearing. Inspection of bilateral ears reveals no masses, swelling, redness or drainage. -

ABBREVIATION LIST ALOC Altered Level of Consciousness ABC's Airway, Breathing, Circulation ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Suppo

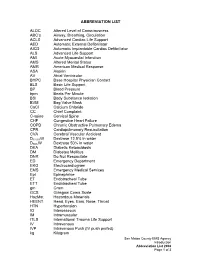

ABBREVIATION LIST ALOC Altered Level of Consciousness ABC’s Airway, Breathing, Circulation ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Support AED Automatic External Defibrillator AICD Automatic Implantable Cardiac Defibrillator ALS Advanced Life Support AMI Acute Myocardial Infarction AMS Altered Mental Status AMR American Medical Response ASA Aspirin AV Atrial Ventricular BHPC Base Hospital Physician Contact BLS Basic Life Support BP Blood Pressure bpm Beats Per Minute BSI Body Substance Isolation BVM Bag Valve Mask CaCl Calcium Chloride CC Chief Complaint C-spine Cervical Spine CHF Congestive Heart Failure COPD Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Edema CPR Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation CVA Cerebral Vascular Accident D12.5%W Dextrose 12.5% in water D50%W Dextrose 50% in water DKA Diabetic Ketoacidosis DM Diabetes Mellitus DNR Do Not Resuscitate ED Emergency Department EKG Electrocardiogram EMS Emergency Medical Services Epi Epinephrine ET Endotracheal Tube ETT Endotracheal Tube gm Gram GCS Glasgow Coma Scale HazMat Hazardous Materials HEENT Head, Eyes, Ears, Nose, Throat HTN Hypertension IO Interosseous IM Intramuscular ITLS International Trauma Life Support IV Intravenous IVP Intravenous Push (IV push prefed) kg Kilogram San Mateo County EMS Agency Introduction Abbreviation List 2008 Page 1 of 3 J Joule LOC Loss of Consciousness Max Maximum mcg Microgram meds Medication mEq Milliequivalent min Minute mg Milligram MI Myocardial Infarction mL Milliliter MVC Motor Vehicle Collision NPA Nasopharyngeal Airway NPO Nothing Per Mouth NS Normal Saline NT Nasal Tube NTG Nitroglycerine NS Normal Saline O2 Oxygen OB Obstetrical OD Overdose OPA Oropharyngeal Airway OPQRST Onset, Provoked, Quality, Region and Radiation, Severity, Time OTC Over the Counter PAC Premature Atrial Contraction PALS Pediatric Advanced Life Support PEA Pulseless Electrical Activity PHTLS Prehospital Trauma Life Support PID Pelvic Inflammatory Disease PO By Mouth Pt. -

EMS Stroke Toolkit

Best Practices to Improve Coordinated Stroke Care for Emergency Medical Service Professionals 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The original publication of this document was a collaboration between the Wisconsin Coverdell Stroke Program and the Minnesota Stroke Program and was made possible through federal funds provided by the Paul Coverdell National Acute Stroke Program (grant cycle 2012-2015) through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The Arkansas Department of Health (ADH) wishes to thank the support of these two programs for allowing this document to be customized for Arkansas. Contributors to the content and production of this toolkit include: Arkansas Acute Stroke Care Task Force • Mack Hutchison, NREMT-P, MHA, MEMS QI Director AR SAVES • Renee Joiner, RN, BSN, Program Director • Tim Vandiver, BS, NRP, RN Arkansas Department of Health • James Bledsoe, MD, FACS, Medical Director of EMS and Trauma • Greg Brown, BA, NRP, Branch Chief - Trauma and EMS • Christy Kresse, NRP, EMS Section Chief • Appathurai Balamurugan, MD, DrPH, MPH, FAAFP, State Chronic Disease Director • Tammie Marshall, MSN, MHA, CNE, RN, DNP, State Stroke Nurse Coordinator • David Vrudny, CPHQ, MPM, MPH(c), Stroke/STEMI Section Chief Mercy Hospital Fort Smith • Nicole Harp, RN, SCRN, Stroke Coordinator Minnesota Stroke Registry Program at the Minnesota Department of Health • Al Tsai, PhD, MPH, Program Director • Megan Hicks, MHA, Quality Improvement Coordinator Wisconsin Coverdell Stroke Program at the Wisconsin Department of Health Services • David J. Fladten, -

New Patient Form

New Patient Form Today’s Date:_______________ __ ______________ __________( / / )_______ ________________________________ Name Date of Birth Street Address Unit City State Zip __________________________________________________________________________________________________ Cell Phone Carrier (for appt reminder texts) Home Phone Email If you prefer not to reCeive text message appointment reminders, please check here: Opt-out of Text Message Reminders Gender Male Female Employer & OcCupation ___________________________________________________ How did you find us and who Can we thank for referring you? ______________________________________________ Have you ever seen a Chiropractor? □ Yes □ No Acupuncturist? □ Yes □ No Nutritionist? □ Yes □ No Would you like to learn aBout Acupuncture? □ Yes □ No Functional Medicine & Clinical Nutrition? □ Yes □ No What are your treatment goals? (anything important to you, eg “I want to be pain free“ or “I want to run a faster raCe”) __________________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________________ Patient Symptoms Is the reason for your visit related to: □Auto Accident □Work Injury □Neither Briefly describe your symptoms: _________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ When did your symptoms begin? ________________________ (estimated date or event) -

Emergency Care

Emergency Care THIRTEENTH EDITION CHAPTER 14 The Secondary Assessment Emergency Care, 13e Copyright © 2016, 2012, 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. Daniel Limmer | Michael F. O'Keefe All Rights Reserved Multimedia Directory Slide 58 Physical Examination Techniques Video Slide 101 Trauma Patient Assessment Video Slide 148 Decision-Making Information Video Slide 152 Leadership Video Slide 153 Delegating Authority Video Emergency Care, 13e Copyright © 2016, 2012, 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. Daniel Limmer | Michael F. O'Keefe All Rights Reserved Topics • The Secondary Assessment • Body System Examinations • Secondary Assessment of the Medical Patient • Secondary Assessment of the Trauma Patient • Detailed Physical Exam continued on next slide Emergency Care, 13e Copyright © 2016, 2012, 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. Daniel Limmer | Michael F. O'Keefe All Rights Reserved Topics • Reassessment • Critical Thinking and Decision Making Emergency Care, 13e Copyright © 2016, 2012, 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. Daniel Limmer | Michael F. O'Keefe All Rights Reserved The Secondary Assessment Emergency Care, 13e Copyright © 2016, 2012, 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. Daniel Limmer | Michael F. O'Keefe All Rights Reserved Components of the Secondary Assessment • Physical examination • Patient history . History of the present illness (HPI) . Past medical history (PMH) • Vital signs continued on next slide Emergency Care, 13e Copyright © 2016, 2012, 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. Daniel Limmer | Michael F. O'Keefe All Rights Reserved Components of the Secondary Assessment • Sign . Something you can see • Symptom . Something the patient tell you • Reassessment is a continual process. Emergency Care, 13e Copyright © 2016, 2012, 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. Daniel Limmer | Michael F. O'Keefe All Rights Reserved Techniques of Assessment • History-taking techniques . -

Chest Auscultation: Presence/Absence and Equality of Normal/Abnormal and Adventitious Breath Sounds and Heart Sounds A

Northwest Community EMS System Continuing Education: January 2012 RESPIRATORY ASSESSMENT Independent Study Materials Connie J. Mattera, M.S., R.N., EMT-P COGNITIVE OBJECTIVES Upon completion of the class, independent study materials and post-test question bank, each participant will independently do the following with a degree of accuracy that meets or exceeds the standards established for their scope of practice: 1. Integrate complex knowledge of pulmonary anatomy, physiology, & pathophysiology to sequence the steps of an organized physical exam using four maneuvers of assessment (inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation) and appropriate technique for patients of all ages. (National EMS Education Standards) 2. Integrate assessment findings in pts who present w/ respiratory distress to form an accurate field impression. This includes developing a list of differential diagnoses using higher order thinking and critical reasoning. (National EMS Education Standards) 3. Describe the signs and symptoms of compromised ventilations/inadequate gas exchange. 4. Recognize the three immediate life-threatening thoracic injuries that must be detected and resuscitated during the “B” portion of the primary assessment. 5. Explain the difference between pulse oximetry and capnography monitoring and the type of information that can be obtained from each of them. 6. Compare and contrast those patients who need supplemental oxygen and those that would be harmed by hyperoxia, giving an explanation of the risks associated with each. 7. Select the correct oxygen delivery device and liter flow to support ventilations and oxygenation in a patient with ventilatory distress, impaired gas exchange or ineffective breathing patterns including those patients who benefit from CPAP. 8. Explain the components to obtain when assessing a patient history using SAMPLE and OPQRST.