Baptists, Fifth Monarchists, and the Reign of King Jesus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Mid-1630S, a Teenager of Welsh Descent by the Name of William Kiffin

P a g e | 1 “AN HONOURABLE ESTEEME OF THE HOLY WORDS OF GOD”: PARTICULAR BAPTIST WORSHIP IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY “I value not the Practice of all Mankind in any thing in God’s Worship, if the Word of God doth not bear witness to it” Benjamin Keach 1 In the mid-1630s, a teenager of Welsh descent by the name of William Kiffin (1616-1701), who had been orphaned as a young boy and subsequently apprenticed to a glover in London, became so depressed about his future prospects that he decided to run away from his master. It was a Sunday when he made good his escape, and in the providence of God, he happened to pass by St. Antholin’s Church, a hotbed of Puritan radicalism, where the Puritan preacher Thomas Foxley was speaking that day on “the duty of servants to masters.” Seeing a crowd of people going into the church, Kiffin decided to join them. Never having heard the plain preaching of a Puritan before, he was deeply convicted by what he heard and was convinced that Foxley’s sermon was intentionally aimed at him. Kiffin decided to go back to his master with the resolve to hear regularly “some of them they called Puritan Ministers.”2 1 The Breach Repaired in God’s Worship: or, Singing of Psalms, Hymns, and Spiritual Songs, proved to be an Holy Ordinance of Jesus Christ (London, 1691), p.69. 2 William Orme, Remarkable Passages in the Life of William Kiffin (London: Burton and Smith, 1823), p.3. In the words of one writer, St. -

Guidance on the Use of Royal Arms, Names and Images

GUIDANCE ON THE USE OF ROYAL ARMS, NAMES AND IMAGES 1 The following booklet summarises the legal position governing the use, for commercial purposes, of the Royal Arms, Royal Devices, Emblems and Titles and of photographs, portraits, engravings, effigies and busts of The Queen and Members of the Royal Family. Guidance on advertising in which reference is made to a Member of the Royal Family, and on the use of images of Members of the Royal Family on articles for sale, is also provided. The Lord Chamberlain’s Office will be pleased to provide guidance when it is unclear as to whether the use of “Arms” etc., may give the impression that there is a Royal connection. 2 TRADE MARKS Section 4 (1) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 states: “A trade mark which consists of or contains – (a) the Royal arms, or any of the principal armorial bearings of the Royal arms, or any insignia or device so nearly resembling the Royal arms or any such armorial bearing as to be likely to be mistaken for them or it, (b) a representation of the Royal crown or any of the Royal flags, (c) a representation of Her Majesty or any Member of the Royal Family, or any colourable imitation thereof, or (d) words, letters or devices likely to lead persons to think that the applicant either has or recently has had Royal patronage or authorisation, shall not be registered unless it appears to the registrar that consent has been given by or on behalf of Her Majesty or, as the case may be, the relevant Member of the Royal Family.” The Lord Chamberlain's Office is empowered to grant the consent referred to in Section 4(1) on behalf of Her Majesty The Queen. -

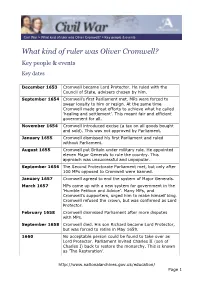

What Kind of Ruler Was Oliver Cromwell? > Key People & Events

Civil War > What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? > Key people & events What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? Key people & events Key dates December 1653 Cromwell became Lord Protector. He ruled with the Council of State, advisers chosen by him. September 1654 Cromwell’s first Parliament met. MPs were forced to swear loyalty to him or resign. At the same time Cromwell made great efforts to achieve what he called ‘healing and settlement’. This meant fair and efficient government for all. November 1654 Cromwell introduced excise (a tax on all goods bought and sold). This was not approved by Parliament. January 1655 Cromwell dismissed his first Parliament and ruled without Parliament. August 1655 Cromwell put Britain under military rule. He appointed eleven Major Generals to rule the country. This approach was unsuccessful and unpopular. September 1656 The Second Protectorate Parliament met, but only after 100 MPs opposed to Cromwell were banned. January 1657 Cromwell agreed to end the system of Major Generals. March 1657 MPs came up with a new system for government in the ‘Humble Petition and Advice’. Many MPs, and Cromwell’s supporters, urged him to make himself king. Cromwell refused the crown, but was confirmed as Lord Protector. February 1658 Cromwell dismissed Parliament after more disputes with MPs. September 1658 Cromwell died. His son Richard became Lord Protector, but was forced to retire in May 1659. 1660 No acceptable person could be found to take over as Lord Protector. Parliament invited Charles II (son of Charles I) back to restore the monarchy. This is known as ‘The Restoration’. -

Why Did Britain Become a Republic? > New Government

Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Why did Britain become a republic? Case study 2: New government Even today many people are not aware that Britain was ever a republic. After Charles I was put to death in 1649, a monarch no longer led the country. Instead people dreamed up ideas and made plans for a different form of government. Find out more from these documents about what happened next. Report on the An account of the Poem on the arrest of setting up of the new situation in Levellers, 1649 Commonwealth England, 1649 Portrait & symbols of Cromwell at the The setting up of Cromwell & the Battle of the Instrument Commonwealth Worcester, 1651 of Government http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/ Page 1 Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Case study 2: New government - Source 1 A report on the arrest of some Levellers, 29 March 1649 (Catalogue ref: SP 25/62, pp.134-5) What is this source? This is a report from a committee of MPs to Parliament. It explains their actions against the leaders of the Levellers. One of the men they arrested was John Lilburne, a key figure in the Leveller movement. What’s the background to this source? Before the war of the 1640s it was difficult and dangerous to come up with new ideas and try to publish them. However, during the Civil War censorship was not strongly enforced. Many political groups emerged with new ideas at this time. One of the most radical (extreme) groups was the Levellers. -

Henry J Essey a Pastor in Politics

Henry Jessey A Pastor in Politics HAVE decided to speak* about Henry Jessey's politics because I of my suspicion that the time is perhaps once more approaching when, while a service of ordination may become optional for the making of a minister of Christ, a prison sentence may yet become obligatory. So I want to uncover for you the motives which took Jessey into politics and the ambiguities and troubles which attended his commitment. Nevertheless, I do not want you to think that I have deluded myself into believing that I have discovered either a seventeenth century English Martin Luther King or yet one more lily-livered liberal mouthing platitudes about 'involvement' from a safe suburban pulpit. Henry Jessey was a man of his time and not ours. His spiritual and political context was not our context, his arguments were not our arguments, his crises were not our crises, but the question remains whether his deepest concern ought to be ours. Jessey, apart, perhaps, from being an Oxbridge man, was nearly everything a Baptist minister ought to be. He had the grace of perseverance and served one congregation for about a quarter of a century. He was friendly to other Christians, at least within decent limits, for neither papists nor unitarians were invited to the ministers' fraternal to which he belonged. He was good with children, though a bachelor, and had even written a book for them. He was an en thusiastic expositor of Scripture and shared, during the 1650's, in a scheme for replacing the King James Version with a new and more accurate one. -

Menasseh Ben Israel and His World Brill's Studies in Intellectual History

MENASSEH BEN ISRAEL AND HIS WORLD BRILL'S STUDIES IN INTELLECTUAL HISTORY General Editor AJ. VANDERJAGT, University of Groningen Editorial Board M. COLISH, Oberlin College J.I. ISRAEL, University College, London J.D. NORTH, University of Groningen R.H. POPKIN, Washington University, St. Louis-UCLA VOLUME 15 MENASSEH BEN ISRAEL AND HIS WORLD EDITED BY YOSEF KAPLAN, HENRY MECHOULAN AND RICHARD H. POPKIN ^o fr-hw'* -A EJ. BRILL LEIDEN • NEW YORK • K0BENHAVN • KÖLN 1989 Published with financial support from the Dr. C. Louise Thijssen- Schoutestichting. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Menasseh Ben Israel and his world / edited by Yosef Kaplan, Henry Méchoulan and Richard H. Popkin. p. cm. -- (Brill's studies in intellectual history, ISSN 0920-8607 ; v. 15) Includes index. ISBN 9004091149 1. Menasseh ben Israel, 1604-1657. 2. Rabbis-Netherlands- -Amsterdam-Biography. 3. Amsterdam (Netherlands)-Biography. 4. Sephardim--Netherlands--Amsterdam--History--17th century. 5. Judaism--Netherlands--Amsterdam--History--17th century. I. Kaplan, Yosef. II. Popkin, Richard Henry, 1923- BM755.M25M46 1989 296'.092-dc20 89-7265 [B] CIP ISSN 0920-8607 ISBN 90 04 09114 9 © Copyright 1989 by E.J. Brill, The Netherlands All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or translated in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm, microfiche or any other means without written permission from the publisher PRINTED IN THE NETHERLANDS BY E.J. BRILI, CONTENTS Introduction, Richard H. Popkin vu A Generation of Progress in the Historical Study of Dutch Sephardic Jewry, Yosef Kaplan 1 The Jewish Dimension of the Scottish Apocalypse: Climate, Cove- nant and World Renewal, Arthur H. -

How Did William Kiffin Join the Baptists?

How did William Kiffin join the Baptists? HE history of the English Particular Baptists before 1644 is a T great deal more difficult to reconstruct in detail than the authors of Baptist textbooks have normally been prepared explicitly to acknowledge. The documents are few, their interpretation is often uncertain and, in addition, some of the very scanty evidence which does exist appears to be in open conflict with the rest. Some of these problems have to be faced in any attempt to disCQver exactly how William Kiffin (1616-1701) came to be, by 1644, the leader of a Baptist congregation. There are two opposing versions of this process. The earlier is Kiffin's own which leaves the clear impression that he joined a congregation of Independent Puritans about 1638 which gradually evolved, under his leadership, into the Baptist church of which he remained pastor until his death. The second account, given by Thomas Crosby in his History of the English Baptists/ suggests that Kiffin first joined an Independent church (per haps that led by Henry Jessey), then joined John Spilsbery's Particular Baptist congregation and eventually, after a disagreement with Spils bery, left that also, presumably to gather his own. It must at once be admitted that there is nothing intrinsically unlikely about either ver sion in a period as turbulent spiritually as politically. Whilst it might at first sight seem that Kiffin's own account is far more likely to be trustworthy both the fact that he wrote at least a quarter of a century after these early events took place and his motive for writing forbid the rejection of Crosby's record without careful discussion. -

The Ultimate Intervention: Revitalising the UN Trusteeship Council for the 21St Century

Centre for European and Asian Studies at Norwegian School of Management Elias Smiths vei 15 PO Box 580 N-1302 Sandvika Norway 3/2003 ISSN 1500-2683 The Ultimate Intervention: Revitalising the UN Trusteeship Council for the 21st Century Tom Parker 0 The Ultimate Intervention: Revitalising the UN Trusteeship Council for the 21st Century Tom Parker April 2003 Tom Parker is a graduate of the London School of Economics (LSE) and Leiden University in The Netherlands. He has degrees in Government and Public International Law. He served for six years as an intelligence officer in the British Security Service (MI5) and four years as a war crimes investigator at the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in The Hague. He is currently a research affiliate at the Executive Session for Domestic Preparedness at the Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, working on the Long-Term Strategy Project For Preserving Security and Democratic Norms in the War on Terrorism. Tom Parker can be contacted at: 54 William Street, New Haven, Connecticut 06511, USA E-mail: [email protected]. A publication from: Centre for European and Asian Studies at Norwegian School of Management Elias Smiths vei 15 PO Box 580 N-1302 Sandvika Norway http://www.bi.no/dep2/ceas/ 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................3 PART I: THE HISTORICAL CONTEXT....................................................................3 A) THE ORIGINS OF THE IDEA OF TRUSTEESHIP .................................................................................. -

Baptist History

180 Baptist History Periodicals Tennessee Baptist History . Vol. 7. Fall 2005. No. 1. (Published annually by TN Baptist Historical Society, 8072 Sunrise Baptist History Circle, Tn 37067). Thomas. Both Sides. New York Independent. Four Editorials. Published as a tract. 1897. Sermons of the 27th Annual Sovereign Grace Conference August 5-7, 2008 Web Sites Gameo—http://www.gameo.org/encyclopedia/contents/ H8358.html Haemestede. Dutch Martyrology— 1559. http:// gracewood0.tripod.com/foxefreeman.html [Mcusa] Mantz.—http://www.mcusa-archives.org/ events/news_release_Anabaptist Library. Edited by —http://www.apostolicchristianchurch.org/ Pages/Library-Anabaptist%20History,% Laurence and Lyndy Justice 20Rise.htm Pilgrim Publications—http://members.aol.com/pilgrimpub/ spurgeon.htm Whitsitt—http://www.lva.lib.va.us/whatwehave/bio/whitsitt/ index.htm —http://geocities.com/Athens/Delphi/8297/diss/dis- c31.htm#N_101_#N-101 Victory Baptist Church 9601 Blue Ridge Extension Kansas City, Missouri 64134 816-761-7184 www.victorybaptist.us Printer’s logo And/or info Bibliography 179 Shackelford, J. A. Compendium of Baptist History . Louisville: Baptist Book Concern, 1892. Spurgeon, C.H. and Susannah, and J.W. Harrald. C.H. Spurgeon: The Early Years and The Full Harvest (2 vols.). Edinburgh: Banner of Truth, 1967. Thomas, Joshua. The American Baptist Heritage in Wales . La- fayette, TN: Church History Research and Archives, 1976. Torbet, Robert G. A History of the Baptists. 1950. Tull. Shapers of Baptist Thought . 1972. —Study of Southern Baptist Landmarkism in the Light of Historical Baptist Ecclesiology . Arno Press, 1980. Verduin, Leonard. The Reformers and Their Stepchildren . Sarasota, Florida: The Christian Hymnary Publishers Reprint, 1997 (First Published in 1964). -

Oliver Cromwell and the Regicides

OLIVER CROMWELL AND THE REGICIDES By Dr Patrick Little The revengers’ tragedy known as the Restoration can be seen as a drama in four acts. The first, third and fourth acts were in the form of executions of those held responsible for the ‘regicide’ – the killing of King Charles I on 30 January 1649. Through October 1660 ten regicides were hanged, drawn and quartered, including Charles I’s prosecutor, John Cooke, republicans such as Thomas Scot, and religious radicals such as Thomas Harrison. In April 1662 three more regicides, recently kidnapped in the Low Countries, were also dragged to Tower Hill: John Okey, Miles Corbett and John Barkstead. And in June 1662 parliament finally got its way when the arch-republican (but not strictly a regicide, as he refused to be involved in the trial of the king) Sir Henry Vane the younger was also executed. In this paper I shall consider the careers of three of these regicides, one each from these three sets of executions: Thomas Harrison, John Okey and Sir Henry Vane. What united these men was not their political views – as we shall see, they differed greatly in that respect – but their close association with the concept of the ‘Good Old Cause’ and their close friendship with the most controversial regicide of them all: Oliver Cromwell. The Good Old Cause was a rallying cry rather than a political theory, embodying the idea that the civil wars and the revolution were in pursuit of religious and civil liberty, and that they had been sanctioned – and victory obtained – by God. -

WORKING PAPER Legitimizing Autocracy: Re-Framing the Analysis of Corporate Relations to Undemocratic Regimes

WP 2020/1 ISSN: 2464-4005 www.nhh.no WORKING PAPER Legitimizing autocracy: Re-framing the analysis of corporate relations to undemocratic regimes Ivar Kolstad Department of Accounting, Auditing and Law Institutt for regnskap, revisjon og rettsvitenskap Legitimizing autocracy: Re-framing the analysis of corporate relations to undemocratic regimes Ivar Kolstad Abstract Recent work in political economy suggests that autocratic regimes have been moving from an approach of mass repression based on violence, towards one of manipulation of information, where highlighting regime performance is a strategy used to boost regime popularity and maintain control. This presents a challenge to normative analyses of the role of corporations in undemocratic countries, which have tended to focus on the concept of complicity. This paper introduces the concept of legitimization, defined as adding to the authority of an agent, and traces out the implications of adopting this concept as a central element of the analysis of corporate relations to autocratic regimes. Corporations confer legitimacy on autocratic governments through a number of material and symbolic activities, including by praising their economic performance. We identify the ethically problematic aspects of legitimization, argue that praise for autocratic regime performance lacks empirical support, and outline a research agenda on legitimization. Keywords: Complicity, legitimization, legitimacy, corporate political activity, democracy Associate Professor, Department of Accounting, Auditing and Law, Norwegian School of Economics, Helleveien 30, N-5045 Bergen, Norway. Tel: +47 55 95 93 24. E-mail: [email protected]. 1 1. Introduction «China’s done an unbelievable job of lifting people out of poverty. They’ve done an incredible job – far beyond what any country has done – we were talking about mid-90s to today – the biggest change is the number of people that have been pulled out of poverty, by far. -

Contextual Information Timelines and Family Trees Tudors to Windsors: British Royal Portraits 16 March – 14 July 2019

16 March — 14 July 2019 British Royal Portraits Exhibition organised by the National Portrait Gallery, London Contextual Information Timelines and Family Trees Tudors to Windsors: British Royal Portraits 16 March – 14 July 2019 Tudors to Windsors traces the history of the British monarchy through the outstanding collection of the National Portrait Gallery, London. This exhibition highlights major events in British (and world) history from the sixteenth century to the present, examining the ways in which royal portraits were impacted by both the personalities of individual monarchs and wider historical change. Presenting some of the most significant royal portraits, the exhibition will explore five royal dynasties: the Tudors, the Stuarts, the Georgians, the Victorians and the Windsors shedding light on key figures and important historical moments. This exhibition also offers insight into the development of British art including works by the most important artists to have worked in Britain, from Sir Peter Lely and Sir Godfrey Kneller to Cecil Beaton and Annie Leibovitz. 2 UK WORLDWIDE 1485 Henry Tudor defeats Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field, becoming King Henry VII The Tudors and founding the Tudor dynasty 1492 An expedition led by Italian explorer Christopher Columbus encounters the Americas 1509 while searching for a Western passage to Asia Henry VII dies and is succeeded Introduction by King Henry VIII 1510 The Inca abandon the settlement of Machu Picchu in modern day Peru Between 1485 and 1603, England was ruled by 1517 Martin Luther nails his 95 theses to the five Tudor monarchs. From King Henry VII who won the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, crown in battle, to King Henry VIII with his six wives and a catalyst for the Protestant Reformation 1519 Elizabeth I, England’s ‘Virgin Queen’, the Tudors are some Hernando Cortes lands on of the most familiar figures in British history.