Representative, Still: the Role of the Senate in Our Democracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Which Political Parties Are Standing up for Animals?

Which political parties are standing up for animals? Has a formal animal Supports Independent Supports end to welfare policy? Office of Animal Welfare? live export? Australian Labor Party (ALP) YES YES1 NO Coalition (Liberal Party & National Party) NO2 NO NO The Australian Greens YES YES YES Animal Justice Party (AJP) YES YES YES Australian Sex Party YES YES YES Pirate Party Australia YES YES NO3 Derryn Hinch’s Justice Party YES No policy YES Sustainable Australia YES No policy YES Australian Democrats YES No policy No policy 1Labor recently announced it would establish an Independent Office of Animal Welfare if elected, however its structure is still unclear. Benefits for animals would depend on how the policy was executed and whether the Office is independent of the Department of Agriculture in its operations and decision-making.. Nick Xenophon Team (NXT) NO No policy NO4 2The Coalition has no formal animal welfare policy, but since first publication of this table they have announced a plan to ban the sale of new cosmetics tested on animals. Australian Independents Party NO No policy No policy 3Pirate Party Australia policy is to “Enact a package of reforms to transform and improve the live exports industry”, including “Provid[ing] assistance for willing live animal exporters to shift to chilled/frozen meat exports.” Family First NO5 No policy No policy 4Nick Xenophon Team’s policy on live export is ‘It is important that strict controls are placed on live animal exports to ensure animals are treated in accordance with Australian animal welfare standards. However, our preference is to have Democratic Labour Party (DLP) NO No policy No policy Australian processing and the exporting of chilled meat.’ 5Family First’s Senator Bob Day’s position policy on ‘Animal Protection’ supports Senator Chris Back’s Federal ‘ag-gag’ Bill, which could result in fines or imprisonment for animal advocates who publish in-depth evidence of animal cruelty The WikiLeaks Party NO No policy No policy from factory farms. -

Chronology of Same-Sex Marriage Bills Introduced Into the Federal Parliament: a Quick Guide

RESEARCH PAPER SERIES, 2017–18 UPDATED 24 NOVEMBER 2017 Chronology of same-sex marriage bills introduced into the federal parliament: a quick guide Deirdre McKeown Politics and Public Administration Section On 15 November 2017, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) announced the results of the voluntary Australian Marriage Law Postal survey. The ABS reported that, of the 79.5 per cent of Australians who expressed a view on the question Should the law be changed to allow same-sex couples to marry?, ‘the majority indicated that the law should be changed to allow same-sex couples to marry, with 7,817,247 (61.6 per cent) responding Yes and 4,873,987 (38.4 per cent) responding No’. On the same day Senator Dean Smith (LIB, WA) introduced, on behalf of eight cross-party co-sponsors, a bill to amend the Marriage Act 1961 (Cth) so as to redefine marriage as ‘a union of two people’. This is the fifth marriage equality bill introduced in the current (45th) Parliament, while six bills were introduced into the previous (44th) Parliament. Since the 2004 amendment to the Marriage Act 1961 (Cth) which inserted the current definition of marriage, 23 bills dealing with marriage equality or the recognition of overseas same-sex marriages have been introduced into the federal Parliament. Four bills have come to a vote: three in the Senate (in 2010, 2012 and 2013), and one in the House of Representatives (in 2012). These bills were all defeated at the second reading stage; consequently no bill has been debated by the second chamber. -

Condolence Motion

CONDOLENCE MOTION 7 May 2014 [3.38 p.m.] Mr BARNETT (Lyons) - I stand in support of the motion moved by the Premier and support entirely the views expressed by the Leader for the Opposition and the member for Bass, Kim Booth. As a former senator, having worked with Brian Harradine in his role as a senator, it was a great privilege to know him. He was a very humble man. He did not seek publicity. He was honoured with a state funeral, as has been referred to, at St Mary's Cathedral in Hobart on Wednesday, 23 April. I know that many in this House were there, including the Premier and the Leader of the Opposition, together with the former Prime Minister, the Honourable John Howard, and also my former senate colleague, Don Farrell, a current senator for South Australia because Brian Harradine was born in South Australia and had a background with the Shop, Distributive and Allied Employees Association. Both gentlemen had quite a bit in common. They knew each other well and it was great to see Don Farrell again and catch up with him. He served as an independent member of parliament from 1975 to 2005, so for some 30 years, and was father of the Senate. Interestingly, when he concluded in his time as father of the Senate, a former senator, John Watson, took over as father of the Senate. Brian Harradine was a values- driven politician and he was a fighter for Tasmania. The principal celebrant at the service was Archbishop Julian Porteous and he did a terrific job. -

Time for Submissions to Inquiry Into Building Inclusive and Accessible Communities

Senate Community Affairs References Committee More time for submissions to inquiry into building inclusive and accessible communities The Senate Community Affairs References Committee is inquiring into the delivery of outcomes under the National DATE REFERRED Disability Strategy 2010-2020 to build inclusive and 29 December 2016 accessible communities. SUBMISSIONS CLOSE The inquiry will examine the planning, design, management 28 April 2017 and regulation of the built and natural environment, transport services and infrastructure, and communication and NEXT HEARING information systems, including barriers to progress or To be advised innovation in these areas. It will also look at the impact of restricted access for people with disability on inclusion and REPORTING DATE participation in all aspects of life. 13 September 2017 The date for submissions to the inquiry has been extended to COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP Friday 28 April 2017. Senator Rachel Siewert (Chair) "The additional time will ensure that groups and individuals Senator Jonathon Duniam can make a contribution to the inquiry" said committee chair, (Deputy Chair) Senator Sam Dastyari Senator Rachel Siewert. "The committee is very keen to hear Senator Louise Pratt directly from people with disability and their families and Senator Linda Reynolds carers, as well as representative organisations. We would also Senator Murray Watt welcome submissions from service providers and innovators Senator Carol Brown who have improved accessibility in their communities or online." CONTACT THE COMMITTEE Senate Standing Committees "The committee encourages people to visit the committee's on Community Affairs website to get some more information about the inquiry and PO Box 6100 how to make a submission. -

KJA Action Items Template

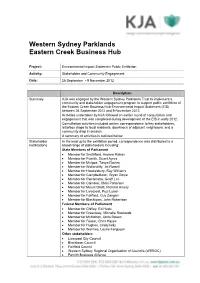

Western Sydney Parklands Eastern Creek Business Hub Project: Environmental Impact Statement Public Exhibition Activity: Stakeholder and Community Engagement Date: 26 September - 9 November 2012 Description Summary KJA was engaged by the Western Sydney Parklands Trust to implement a community and stakeholder engagement program to support public exhibition of the Eastern Creek Business Hub Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) between 26 September 2012 and 9 November 2012. Activities undertaken by KJA followed an earlier round of consultation and engagement that was completed during development of the EIS in early 2012. Consultation activities included written correspondence to key stakeholders, letterbox drops to local residents, doorknock of adjacent neighbours, and a community drop in session. A summary of activities is outlined below. Stakeholder In the lead up to the exhibition period, correspondence was distributed to a notifications broad range of stakeholders including: State Members of Parliament Member for Smithfield, Andrew Rohan Member for Penrith, Stuart Ayres Member for Mulgoa, Tanya Davies Member for Wollondilly, Jai Rowell Member for Hawkesbury, Ray Williams Member for Campbelltown, Bryan Doyle Member for Parramatta, Geoff Lee Member for Camden, Chris Patterson Member for Mount Druitt, Richard Amery Member for Liverpool, Paul Lynch Member for Fairfield, Guy Zangari Member for Blacktown, John Robertson Federal Members of Parliament Member for Chifley, Ed Husic Member for Greenway, Michelle Rowlands Member for -

Williams V Commonwealth: Commonwealth Executive Power

CASE NOTE WILLIAMS v COMMONWEALTH* COMMONWEALTH EXECUTIVE POWER AND AUSTRALIAN FEDERALISM SHIPRA CHORDIA, ** ANDREW LYNCH† AND GEORGE WILLIAMS‡ A majority of the High Court in Williams v Commonwealth held that the Common- wealth executive does not have a general power to enter into contracts and spend public money absent statutory authority or some other recognised source of power. This article surveys the Court’s reasoning in reaching this surprising conclusion. It also considers the wider implications of the case for federalism in Australia. In particular, it examines: (1) the potential use of s 96 grants to deliver programs that have in the past been directly funded by Commonwealth executive contracts; and (2) the question of whether statutory authority may be required for the Commonwealth executive to participate in inter- governmental agreements. CONTENTS I Introduction .............................................................................................................. 190 II Background ............................................................................................................... 191 III Preliminary Issues .................................................................................................... 194 A Standing ........................................................................................................ 194 B Section 116 ................................................................................................... 196 C Validity of Appropriation .......................................................................... -

Evobzq5zilluk8q2nary.Pdf

NOVEMBER 10 (GMT) – NOVEMBER 11 (AEST), 2020 YOUR DAILY TOP 12 STORIES FROM FRANK NEWS FULL STORIES START ON PAGE 3 NORTH AMERICA UK AUSTRALIA Trump blocks co-operation Optimism over vaccine rollout MP quits Labor frontbench The Trump administration threw the A coronavirus vaccine could start being Labor right faction warrior Joel Fitzgibbon presidential transition into tumult, distributed by Christmas after a jab has urged his party to make a major with President Donald Trump blocking developed by pharmaceutical giant shift on the environment and blue-collar government officials from co-operating Pfizer cleared a “significant hurdle”. voters after quitting shadow cabinet. with President-elect Joe Biden’s team Prime Minister Boris Johnson said initial Western Sydney MP Ed Husic replaced and Attorney General William Barr results suggested the vaccine was 90 per Fitzgibbon as the opposition’s resources authorizing the Justice Department to cent effective at protecting people from and agriculture spokesman after the probe unsubstantiated allegations of COVID-19 but warned these were “very, stunning resignation. Fitzgibbon has voter fraud. Some Republicans, including very early days”. been increasingly outspoken in a bruising Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, battle over energy policy with senior rallied behind Trump’s efforts to fight the figures from Labor’s left flank. election results. NORTH AMERICA UK NEW ZEALAND Election probes given OK Redundancies hit record high Napier braces for heavy rain Attorney General William Barr has More people were made redundant Flood-hit Napier residents remain on authorized federal prosecutors across between July and September than at any alert as more heavy rain is falling on the US to pursue “substantial allegations” point on record, according to new official the city, with another day of rain still to of voting irregularities, if they exist, before statistics, as the pandemic laid waste come. -

Balance of Power Senate Projections, Spring 2018

Balance of power Senate projections, Spring 2018 The Australia Institute conducts a quarterly poll of Senate voting intention. Our analysis shows that major parties should expect the crossbench to remain large and diverse for the foreseeable future. Senate projections series, no. 2 Bill Browne November 2018 ABOUT THE AUSTRALIA INSTITUTE The Australia Institute is an independent public policy think tank based in Canberra. It is funded by donations from philanthropic trusts and individuals and commissioned research. We barrack for ideas, not political parties or candidates. Since its launch in 1994, the Institute has carried out highly influential research on a broad range of economic, social and environmental issues. OUR PHILOSOPHY As we begin the 21st century, new dilemmas confront our society and our planet. Unprecedented levels of consumption co-exist with extreme poverty. Through new technology we are more connected than we have ever been, yet civic engagement is declining. Environmental neglect continues despite heightened ecological awareness. A better balance is urgently needed. The Australia Institute’s directors, staff and supporters represent a broad range of views and priorities. What unites us is a belief that through a combination of research and creativity we can promote new solutions and ways of thinking. OUR PURPOSE – ‘RESEARCH THAT MATTERS’ The Institute publishes research that contributes to a more just, sustainable and peaceful society. Our goal is to gather, interpret and communicate evidence in order to both diagnose the problems we face and propose new solutions to tackle them. The Institute is wholly independent and not affiliated with any other organisation. Donations to its Research Fund are tax deductible for the donor. -

A Decade of Australian Anti-Terror Laws

A DECADE OF AUSTRALIAN ANTI-TERROR LAWS GEORGE WILLIAMS* [This article takes stock of the making of anti-terror laws in Australia since 11 September 2001. First, it catalogues and describes Australia’s record of enacting anti-terror laws since that time. Second, with the benefit of perspective that a decade brings, it draws conclusions and identifies lessons about this body of law for the Australian legal system and the ongoing task of protecting the community from terrorism.] CONTENTS I Introduction ..........................................................................................................1137 II Australia’s Anti-Terror Laws ................................................................................1139 A Number of Federal Anti-Terror Laws ......................................................1140 1 Defining an Anti-Terror Law ......................................................1141 2 How Many Anti-Terror Laws? ....................................................1144 B Scope of Federal Anti-Terror Laws .........................................................1146 1 The Definition of a ‘Terrorist Act’ ..............................................1146 2 Offence of Committing a ‘Terrorist Act’ and Preparatory Offences ......................................................................................1146 3 Proscription Regime ....................................................................1147 4 Financing Offences and Regulation ............................................1147 (a) Offences ..........................................................................1147 -

Introduction to Volume 1 the Senators, the Senate and Australia, 1901–1929 by Harry Evans, Clerk of the Senate 1988–2009

Introduction to volume 1 The Senators, the Senate and Australia, 1901–1929 By Harry Evans, Clerk of the Senate 1988–2009 Biography may or may not be the key to history, but the biographies of those who served in institutions of government can throw great light on the workings of those institutions. These biographies of Australia’s senators are offered not only because they deal with interesting people, but because they inform an assessment of the Senate as an institution. They also provide insights into the history and identity of Australia. This first volume contains the biographies of senators who completed their service in the Senate in the period 1901 to 1929. This cut-off point involves some inconveniences, one being that it excludes senators who served in that period but who completed their service later. One such senator, George Pearce of Western Australia, was prominent and influential in the period covered but continued to be prominent and influential afterwards, and he is conspicuous by his absence from this volume. A cut-off has to be set, however, and the one chosen has considerable countervailing advantages. The period selected includes the formative years of the Senate, with the addition of a period of its operation as a going concern. The historian would readily see it as a rational first era to select. The historian would also see the era selected as falling naturally into three sub-eras, approximately corresponding to the first three decades of the twentieth century. The first of those decades would probably be called by our historian, in search of a neatly summarising title, The Founders’ Senate, 1901–1910. -

Modelling Elections Submission to ERRE: Special Committee on Electoral Reform Byron Weber Becker [email protected]

Modelling Elections Submission to ERRE: Special Committee on Electoral Reform Byron Weber Becker [email protected] Summary I have done extensive computer modelling of six different electoral systems being proposed for Canada. The detailed results inform five recommendations regarding the systems. The two most prominent are that (1) Alternative Vote violates the Effectiveness and Legitimacy test in the Committee’s mandate and (2) the Rural- Urban PR model advanced by Fair Vote Canada is highly proportional and has objective advantages relative to Single Transferable Vote and Mixed Member Proportional. When I was eighteen my family moved and needed a new home. We decided to build one of Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic domes – five-eighths of a sphere made from triangles with an unusual use of space inside the home. We decided on a dome in spite of the fact that we had only seen pictures of such a home. This lack of experience was a problem when faced with the decision of whether to build a massive, 7-meter-tall fireplace (at considerable expense) as a focal point in the middle of the dome. The answer became clear when we built a scale model of the dome out of cardboard with a removable fireplace. We could get a preview of how the home would feel with the fireplace and without the fireplace. As a result of this modelling, the fireplace was built and we were delighted with the result. Canada is now faced with designing something we have little direct experience with and considerably more complex than a geodesic dome. -

Bicameralism in the New Zealand Context

377 Bicameralism in the New Zealand context Andrew Stockley* In 1985, the newly elected Labour Government issued a White Paper proposing a Bill of Rights for New Zealand. One of the arguments in favour of the proposal is that New Zealand has only a one chamber Parliament and as a consequence there is less control over the executive than is desirable. The upper house, the Legislative Council, was abolished in 1951 and, despite various enquiries, has never been replaced. In this article, the writer calls for a reappraisal of the need for a second chamber. He argues that a second chamber could be one means among others of limiting the power of government. It is essential that a second chamber be independent, self-confident and sufficiently free of party politics. I. AN INTRODUCTION TO BICAMERALISM In 1950, the New Zealand Parliament, in the manner and form it was then constituted, altered its own composition. The legislative branch of government in New Zealand had hitherto been bicameral in nature, consisting of an upper chamber, the Legislative Council, and a lower chamber, the House of Representatives.*1 Some ninety-eight years after its inception2 however, the New Zealand legislature became unicameral. The Legislative Council Abolition Act 1950, passed by both chambers, did as its name implied, and abolished the Legislative Council as on 1 January 1951. What was perhaps most remarkable about this transformation from bicameral to unicameral government was the almost casual manner in which it occurred. The abolition bill was carried on a voice vote in the House of Representatives; very little excitement or concern was caused among the populace at large; and government as a whole seemed to continue quite normally.