Tat Lan Hydrological Masterplan Volume I 1 INTRODUCTION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rakhine State Needs Assessment September 2015

Rakhine State Needs Assessment September 2015 This document is published by the Center for Diversity and National Harmony with the support of the United Nations Peacebuilding Fund. Publisher : Center for Diversity and National Harmony No. 11, Shweli Street, Kamayut Township, Yangon. Offset : Public ation Date : September 2015 © All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Rakhine State, one of the poorest regions in Myanmar, has been plagued by communal problems since the turn of the 20th century which, coupled with protracted underdevelopment, have kept residents in a state of dire need. This regrettable situation was compounded from 2012 to 2014, when violent communal riots between members of the Muslim and Rakhine communities erupted in various parts of the state. Since the middle of 2012, the Myanmar government, international organisations and non-governmen- tal organisations (NGOs) have been involved in providing humanitarian assistance to internally dis- placed and conflict-affected persons, undertaking development projects and conflict prevention activ- ities. Despite these efforts, tensions between the two communities remain a source of great concern, and many in the international community continue to view the Rakhine issue as the biggest stumbling block in Myanmar’s reform process. The persistence of communal tensions signaled a need to address one of the root causes of conflict: crushing poverty. However, even as various stakeholders have attempted to restore normalcy in the state, they have done so without a comprehensive needs assessment to guide them. In an attempt to fill this gap, the Center for Diversity and National Harmony (CDNH) undertook the task of developing a source of baseline information on Rakhine State, which all stakeholders can draw on when providing humanitarian and development assistance as well as when working on conflict prevention in the state. -

Download Report

Emergency Market Mapping and Analysis (EMMA) Understanding the Fish Market System in Kyauk Phyu Township Rakhine State. Annex to the Final report to DfID Post Giri livelihoods recovery, Kyaukphyu Township, Rakhine State February 14 th 2011 – November 13 th 2011 August 2011 1 Background: Rakhine has a total population of 2,947,859, with an average household size of 6 people, (5.2 national average). The total number of households is 502,481 and the total number of dwelling units is 468,000. 1 On 22 October 2010, Cyclone Giri made landfall on the western coast of Rakhine State, Myanmar. The category four cyclonic storm caused severe damage to houses, infrastructure, standing crops and fisheries. The majority of the 260,000 people affected were left with few means to secure an income. Even prior to the cyclone, Rakhine State (RS) had some of the worst poverty and social indicators in the country. Children's survival and well-being ranked amongst the worst of all State and Divisions in terms of malnutrition, with prevalence rates of chronic malnutrition of 39 per cent and Global Acute Malnutrition of 9 per cent, according to 2003 MICS. 2 The State remains one of the least developed parts of Myanmar, suffering from a number of chronic challenges including high population density, malnutrition, low income poverty and weak infrastructure. The national poverty index ranks Rakhine 13 out of 17 states, with an overall food poverty headcount of 12%. The overall poverty headcount is 38%, in comparison the national average of poverty headcount of 32% and food poverty headcount of 10%. -

The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations Jacques Leider

The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations Jacques Leider To cite this version: Jacques Leider. The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations. Morten Bergsmo; Wolfgang Kaleck; Kyaw Yin Hlaing. Colonial Wrongs and Access to International Law, 40, Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher, pp.177-227, 2020, Publication Series, 978-82-8348-134-1. hal- 02997366 HAL Id: hal-02997366 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02997366 Submitted on 10 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Public Domain Colonial Wrongs and Access to International Law Morten Bergsmo, Wolfgang Kaleck and Kyaw Yin Hlaing (editors) E-Offprint: Jacques P. Leider, “The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations”, in Morten Bergsmo, Wolfgang Kaleck and Kyaw Yin Hlaing (editors), Colonial Wrongs and Access to International Law, Torkel Opsahl Academic EPub- lisher, Brussels, 2020 (ISBNs: 978-82-8348-133-4 (print) and 978-82-8348-134-1 (e- book)). This publication was first published on 9 November 2020. TOAEP publications may be openly accessed and downloaded through the web site https://www.toaep.org which uses Persistent URLs (PURLs) for all publications it makes available. -

Rakhine State, Myanmar

World Food Programme S P E C I A L R E P O R T THE 2018 FAO/WFP AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SECURITY MISSION TO RAKHINE STATE, MYANMAR 12 July 2019 Photographs: ©FAO/F. Del Re/L. Castaldi and ©WFP/K. Swe. This report has been prepared by Monika Tothova and Luigi Castaldi (FAO) and Yvonne Forsen, Marco Principi and Sasha Guyetsky (WFP) under the responsibility of the FAO and WFP secretariats with information from official and other sources. Since conditions may change rapidly, please contact the undersigned for further information if required. Mario Zappacosta Siemon Hollema Senior Economist, EST-GIEWS Senior Programme Policy Officer Trade and Markets Division, FAO Regional Bureau for Asia and the Pacific, WFP E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Please note that this Special Report is also available on the Internet as part of the FAO World Wide Web www.fao.org Please note that this Special Report is also available on the Internet as part of the FAO World Wide Web www.fao.org at the following URL address: http://www.fao.org/giews/ The Global Information and Early Warning System on Food and Agriculture (GIEWS) has set up a mailing list to disseminate its reports. To subscribe, submit the Registration Form on the following link: http://newsletters.fao.org/k/Fao/trade_and_markets_english_giews_world S P E C I A L R E P O R T THE 2018 FAO/WFP AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SECURITY MISSION TO RAKHINE STATE, MYANMAR 12 July 2019 FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS WORLD FOOD PROGRAMME Rome, 2019 Required citation: FAO. -

Grievance Mechanism Procedure (GMP)

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (EIA) REPORT PROPOSED 135 MW KYAUK PHYU COMBINED CYCLE POWER PLANT PROJECT AT KYAUK PHYU TOWNSHIP RAKHINE STATE, MYANMAR ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (EIA) PROPOSED 135 MW KYAUK PHYU COMBINED CYCLE POWER PLANT PROJECT AT KYAUKPHYU TOWNSHIP, RAKHINE STATE, MYANMAR REPORT May 2020 Preparedfor Kyauk Phyu Electric Power Company Limited Prepared by ENVIRON Myanmar Company Limited ProjectNumber: ST190002 Environmental Impact Assessment Proposed 135 MW Kyauk Phyu CCPP Project, Kyauk Phyu Township, Rakhine State, Myanmar Contents 1 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 1-1 1.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Statement Of Need ......................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.3 Project Description .......................................................................................................................... 1-2 1.4 Existing Environment ...................................................................................................................... 1-8 1.5 Assessment of Impacts ................................................................................................................. 1-10 1.6 Environmental Management Plan (EMP) .................................................................................... -

“Caged Without a Roof” Apartheid in Myanmar’S Rakhine State

“CAGED WITHOUT A ROOF” APARTHEID IN MYANMAR’S RAKHINE STATE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Rohingya children in a rural village in Buthidaung township, northern Rakhine State, (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. March 2016. © Amnesty International. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 16/7436/2017 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS TIMELINE OF KEY EVENTS 8 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 10 METHODOLOGY 16 1. BACKGROUND 19 1.1 A HISTORY OF DISCRIMINATION AND PERSECUTION 20 1.2 THE 2012 VIOLENCE AND DISPLACEMENT 22 1.3 FURTHER VIOLENCE AND DISPLACEMENT: 2016 23 1.4 ARSA ATTACKS AND THE CAMPAIGN OF ETHNIC CLEANSING: 2017 24 1.5 THE POLITICAL CONTEXT 25 1.6 UNDERSTANDING ETHNIC RAKHINE GRIEVANCES 26 2. -

Kyaukpyu Township and Ramree Township Rakhine State

NEPAL BHUTAN INDIA CHINA Myanmar Information Management Unit BANGLADESH VIETNAM Kyaukpyu Township and Ramree Township LAOS THAILAND Rakhine State CAMBODIA 93°30'E 93°40'E 93°50'E Chaung Gyi Hpyar (198722) Thea Tan (198470) (Shwe Nyo Ma) Laung Khoke Taung (Ngwe Twin Tu) (198682) (Thea Tan) (Ya Ta Na) Ywar Thit (198687) (Ya Ta Na) Min Gan (198708) (Min Gan) Chon Swei (198697) (Chon Swei) Lawt Te (198709) La Har Gyi (198715) (Min Gan) (La Har Gyi) Ywar Thit Kay (198716) (La Har Gyi) Ah Nauk Hmyar Tein (198685) (Ya Ta Na) Taung Shey (198725) Nga Hpyin Thet (198718) (War Taung) (La Har Gyi) Ah Shey Hmyar Tein (198683) (Ya Ta Na) Doe Tan (198712) (Min Gan) Ma Ra Zaing (198713) Kon Pa Ni Zay (198466) Ka Nyin Taw (198711) (Min Gan) Mauk Tin Gyi (198714) La Man Chaung (198694) Myone Pyin (198681) (Taung Yin) (Min Gan) (Min Gan) (Pan Taw Pyin) (Ya Ta Na) Kyaukpyu War Taung (198724) (War Taung) Taung Yin (198465) Ka Nyin Taw (198469) Say Poke Kay (198486) (Taung Yin) (Taung Yin) (Gone Chein) Ku Lar Bar Taung (198468) Pyin Hpyu Maw (198464) Kywe Te (198695) Ah Htet Pyin (198483) (Taung Yin) (Pyin Hpyu Maw) (Pan Taw Pyin) (Gone Chein) Ah Shey Bat (198487) Nga/La Pwayt (198467) (Gone Chein) (Taung Yin) Pan Taw Pyin (West) (198692) Ya Ta Na (198680) Aung Zay Di (198488) (Ya Ta Na) (Gone Chein) Lay Dar Pyin (198484) (Pan Taw Pyin) (Gone Chein) Kyauk Tin Seik (198492) Saing Chon Dwain (198542) Ku Toet Seik (198696) Pan Taw Pyin (East) (198693) (Ohn Taw) (Saing Chon) (Pan Taw Pyin) (Pan Taw Pyin) Kone Baung (198493) Saing Chon (North) (198540) (Ohn Taw) -

Conflict and Mass Violence in Arakan (Rakhine State): the 1942 Events and Political Identity Formation

Jacques P. Leider (Ecole française d’Extrême-Orient, Yangon) February 2017 Conflict and mass violence in Arakan (Rakhine State): the 1942 events and political identity formation Following the Japanese invasion of Lower Burma in early 1942, the British administration in Arakan1 collapsed in late March/early April. In a matter of days, communal violence broke out in the rural areas of central and north Arakan (Akyab and Kyaukphyu districts). Muslim villagers from Chittagong who had settled in Arakan since the late 19th century were attacked, driven away or killed in Minbya, Myebon, Pauktaw and other townships of central Arakan. A few weeks later, Arakanese Buddhist villagers living in the predominantly Muslim townships of Maungdaw and Buthidaung were taken on by Chittagonian Muslims, their villages destroyed and people killed in great numbers. Muslims fled to the north while Buddhists fled to the south and from 1942 to 1945, the Arakanese countryside was ethnically divided between a Muslim north and a Buddhist south. Several thousand Buddhists and Muslims were relocated by the British to camps in Bengal. The unspeakable outburst of violence has been described with various expressions, such as “massacre”, “bitter battle” or “communal riot” reflecting different interpretations of what had happened. In the 21st century, the description “ethnic cleansing” would likely be considered as a legally appropriate term. Buddhists and Muslims alike see the 1942 violence as a key moment of their ongoing ethno-religious and political divide. The waves of communal clashes of 1942 have been poorly documented, sparsely investigated and rarely studied.2 They are not recorded in standard textbooks on Burma/Myanmar and, surprisingly, they were even absent from contemporary reports and articles that described Burma’s situation during and after World War 1 Officially named Rakhine State after 1989. -

Myanmar Humanitarian

Myanmar Humanitarian Situation Report No. 1 2020 © UNICEF/2020/MaungMaungOo Reporting Period: 1 to 31 January 2020 Highlights Situation in Numbers 362,000 • In response to the COVID-19 outbreak, UNICEF’s focus has been on child- friendly risk communication messages in a number of ethnic languages to children in need of promote good hygiene and hand-washing behaviors to reduce humanitarian assistance transmission and spread. UNICEF is also issuing a U-Report “chatbot” to (HNO 2020) provide basic information and advice reaching over 33,000 young people countrywide. 986,000 people in need • UNICEF and the Mine Risk Working Group (MRWG) recorded 36 casualties (HNO 2020) in January of whom 15 were children, and of five deaths, four were children. 274,000 internally displaced people • During the visit of the Special Representative of the Secretary General for (HNO 2020) Children and Armed Conflict, she acknowledged the progress made by the Government with regards to the 2012 Joint Action Plan on the recruitment and use of children and urged continued engagement and a new joint 470,000 action plan to better protect children and end killing, maiming and sexual non-displaced stateless in violence. Rakhine UNICEF’s Response and Funding Status UNICEF Appeal 2020 SAM Admission 4% US$ 46 million Nutrition Funding status 13% Funding Status (in US$) Access to healthcare 9% Carry- forward Health Funding status 11% $6M Hygiene items distributed 9% WASH Funding status 17% People with MHPSS 28% Child Funding Funding status 8% Protection gap $40M Children in school 31% Funding status 14% Education 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% 1 Funding Overview and Partnerships UNICEF appeals for US$ 46.04 million to sustain provision of critical and life-saving services for children and their caregivers in Myanmar. -

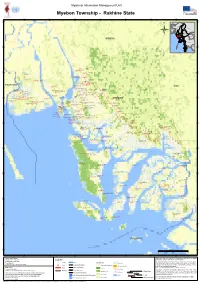

Myebon Township - Rakhine State

Myanmar Information Management Unit Myebon Township - Rakhine State 93°15'E 93°20'E 93°25'E 93°30'E 93°35'E 93°40'E 93°45'E 20°20'N 20°20'N BHUTAN INDIA CHINA BANGLADESH Ü VIETNAM LAOS MINBYA THAILAND CAMBODIA 20°15'N 20°15'N Kyar Inn Taung (197349) (Shauk Chon) Shauk Chon (197347) (Shauk Chon) Kyant Hin Khar (197348) 20°10'N 20°10'N Thin Ga Net (197358) (Shauk Chon) (Thin Ga Net) Kyauk Nga Nwar (197286) Ka Paing Chaung (197335) (Kyauk Nga Nwar) (Pin Kat Chaung) Ah Lel Kyun (197257) (Ah Lel Kyun) Ah Twin Nga Khu Chaung (197258) (Ah Twin Nga Khu Chaung) Chaung Gyi (197336) (Pin Kat Chaung) Pin Kat Taung Maw (197332) Kant Kaw Chaung (197337) (Pin Kat Taung Maw) (Pin Kat Chaung) Kat Taung Swea (197334) Pin Kat Taung Auk (197333) (Pin Kat Taung Maw) PAUKTAW Wet Gaung (197280) (Pin Kat Taung Maw) (Gaung Hpyu) ANN Thar Yar Wa Di (197273) Bar Wai (197338) (Daing Bon) (Pin Kat Chaung) War Khoke Chaung (197370) Mi Kyaung Tet (197368) Myauk Kyein Paik Seik (217990) Ta Laing Pyin (197269) Kyauk Tan (197330) (Yet Chaung) (Yet Chaung) (Myauk Kyein) (Chon Chaung) Myauk Kyein (197303) (Pe Kauk) Pe Kauk (197329) Daing Bon (197271) (Pe Kauk) (Daing Bon) (Myauk Kyein) Dagon (197279) Chaung Shey (197340) (Gaung Hpyu) (Pin Kat Chaung) Tha Pyay Taw (197369) Ta Dar U (197304) (Yet Chaung) Lay Taung (197367) (Myauk Kyein) Kyauk Hpya Lar (197282) Nga Sin Pone (197339) (Yet Chaung) Kan Thar (197278) (Kyauk Hpya Lar) (Pin Kat Chaung) Yet Chaung (197366) Nga Man Ye Gyi (197306) (Gaung Hpyu) Pin Khar (197266) Gaung Hpyu (197277) (Yet Chaung) (Nga Man Ye Gyi) Pyin -

Draft Restricted

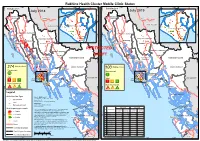

Rakhine Health Cluster Mobile Clinic Status N N N N ' ' ' ' 0 0 92°30'E 93°0'E 93°30'E 0 92°30'E 93°0'E 93°30'E 0 3 3 3 3 ° ° ° ° 1 1 Bangladesh 1 Bangladesh 1 2 2 July 2018 2 July 2019 2 MAUNGDAW MAUNGDAW TOWNSHIP Paletwa TOWNSHIP Paletwa CHIN STATE CHIN STATE SITTWE TOWNSHIP SITTWE TOWNSHIP BUTHIDAUNG TOWNSHIP N N N N ' ' ' BUTHIDAUNG TOWNSHIP ' 0 0 0 0 ° ° ° ° 1 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 KYAUKTAW TOWNSHIP KYAUKTAW TOWNSHIP Buthidaung Sittwe Buthidaung Sittwe Maungdaw Kyauktaw Maungdaw Kyauktaw RESTRICTED MRAUK-U TOWNSHIP MRAUK-U TOWNSHIP Mrauk-U DRAFT Mrauk-U RATHEDAUNG RATHEDAUNG PONNAGYUN PONNAGYUN TOWNSHIP RAKHINE STATE TOWNSHIP RAKHINE STATE N TOWNSHIP N N TOWNSHIP N ' ' ' ' 0 0 0 0 3 Rathedaung 3 3 Rathedaung 3 ° ° ° ° 0 0 0 0 2 2 2 2 Mobile clinics MINBYA TOWNSHIP Mobile clinics MINBYA TOWNSHIP Minbya 274 Ponnagyun Minbya 100 Ponnagyun Government Government 116 PAUKTAW PAUKTAW TOWNSHIP 1 TOWNSHIP Joint ANN TOWNSHIP SITTWE Joint SITTWE ANN TOWNSHIP Pauktaw Pauktaw TOWNSHIP TOWNSHIP 7 6 4 Sittwe Sittwe 1 4 5 Non Government Non Government N N N N ' Myebon ' ' Myebon ' 0 0 0 0 ° ° ° ° 0 81 39 12 0 0 0 2 2 2 54 21 8 2 Legend MYEBON TOWNSHIP MYEBON TOWNSHIP Clinic Provider Type Map ID: MIMU1546v04 Creation Date: 17 September 2019 Government Paper Size: A3 Joint Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 Data Source: Non-Government Health Cluster (Rakhine State) Base map: MIMU Visit frequency per month July 2018 July 2019 Clinics not displayed in the maps because of missing geographic No Township Mobile Vistits/ Mobile Vistits/ < 4 visits coordinates: 9 locations in 2018 and 6 locations in 2019 N N N Clinics Month Clinics Month N ' Place Names: General Administration Department (GAD) and field ' ' ' 0 0 0 0 3 sources.Place names on this product are in line with the general 3 3 3 ° ° ° 1 Sittwe 92 404 56 328 ° 9 4 - 8 visits cartographic practice to reflect the names of such places as 9 9 9 1 KYAUKPYU TOWNSHIP 1 1 2 Buthidaung 64 85 6 8 KYAUKPYU TOWNSHIP 1 designated by the government concerned. -

Arakan (Rakhine State) a Land in Conflict on Myanmar’S Western Frontier AUTHOR: Martin Smith

Arakan (Rakhine State) A Land in Conflict on Myanmar’s Western Frontier AUTHOR: Martin Smith DESIGN: Guido Jelsma PHOTO CREDITS: Tom Kramer (TK) Martin Smith (MS) The Irrawaddy (IR) Agence France-Presse (AFP) European Pressphoto Agency (EPA) Mizzima (MZ) Reuters (RS) COVER PHOTO: Displaced Rakhine woman fetching water in IDP camp near Sittwe (TK) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: This publication was made possible through the financial support of Sweden. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of TNI and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the donor. PUBLICATION DETAILS: Contents of the report may be quoted or reproduced for non-commercial purposes, provided that the source of information is properly cited. ISBN 978-90-70563-69-1 TRANSNATIONAL INSTITUTE (TNI) De Wittenstraat 25, 1052 AK Amsterdam, The Netherlands Tel: +31-20-6626608, Fax: +31-20-6757176 e-mail: [email protected] www.tni.org/en/myanmar-in-focus Amsterdam, December 2019 2 | Arakan (Rakhine State): A Land in Conflict on Myanmar’s Western Frontier transnationalinstitute Table of Contents Myanmar Map 3 Arakan Political Timeline 4 Abbreviations 6 1. Introduction 8 Arakan Map 11 2. The Forgotten Kingdom of Arakan 12 A Legacy of Conflict and Colonisation 12 Rakhine State: A Contemporary Snapshot 15 British Rule and the Development of Nationalist Movements 17 Japanese Invasion and Inter-communal Violence 19 The Marginalisation of Arakan and Rush to Independence 21 Rakhine, Rohingya and the “Politics of Labelling” 25 3. The Parliamentary Era (1948-62) 28 A Country Goes Underground 28 Electoral Movements Revive 29 “Arms for Democracy”: Peace Breakthroughs and Political Failures 31 The Mayu Frontier Administration and Ne Win’s Seizure of Power 34 4.