Messy Love: Collection of Short Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Training Video #1 - How Married Couples Learn to Be Sponsors/Mentors

Training Video #1 - How married couples learn to be sponsors/mentors. If you are a marriage educator, adapt these ideas to your situation. INTRODUCTION THE VIDEO and ADDITIONAL RESOURCES WHAT IS A "SPONSOR COUPLE" AND WHAT DO THEY DO? HOW DO YOU KNOW WHETHER YOU CAN DO THIS? THE DESIGN OF THE PROGRAM PREPARING YOURSELVES…BEFORE YOU MEET WITH AN ENGAGED COUPLE LEARNING TO USE EACH OTHER’S STRENGTHS DECIDING WHERE TO MEET MINIMIZING DISTRACTIONS SNACKS & BREAKS PRAYER DEALING WITH QUESTIONS SCHEDULING THE SESSIONS FIRST SESSION THE FOUR RULES INTRODUCING THE CANDLE AND PRAYER DIALGOGUE / DISCUSSION WITH THE ENGAGED COUPLE DEALING WITH UNEXPECTED CHALLENGES RESOURCES A TYPICAL SESSION WITH THE ENGAGED FOLLOW UP CONCLUSION OF VIDEO ONE INTRODUCTION [TRAINER: So, if you are here today because you think have the “perfect marriage,” I would say that you are the one couple I would encourage to find another ministry. You need to be a “normally nutty” couple to able to help those just beginning the journey of Christian marriage. While these books (For Better and For Ever) provide really good information, it is your own life experience through the good times and terrible times of marriage that will help engaged couples learn to survive and grow as married couples. People getting married today are scared that they might not be successful. It does not help them to meet “the perfect couple.” They need to know that normal “nutty” couples …like them…can survive the challenges of marriage. ] NARRATOR: Welcome to the ministry of marriage preparation. · The task of the church is to teach people how to live the gospel of Jesus. -

Pdf, 147.07 KB

The crew visits the lush FOREST MOON OF GRENLYND and find that shrinking down just makes bigger problems. DAR pulls a PLECK. A marriage is consummated. [Dramatic science-fiction music plays, like the text crawl at the beginning of Star Wars] NARRATOR: The period of civil war has ended. The rebels have defeated the evil Galactic Monarchy and established the harmonious Federated Alliance. Now, ambassador Pleck Decksetter and his intrepid crew travel the farthest reaches of the galaxy to explore astounding new worlds, discover their heroic destinies, and meet weird bug creatures and stuff. This is [echoing] Mission to Zyxx! [Music becomes more dramatic and trumpet-y, then fades away] PLECK: Hey, Dar? DAR: Yeah, what’s up? PLECK: Um-- [quietly] Can I ask you, like, a personal question? DAR: No. PLECK: Okay. [pause] Hey, C-53? C-53: [whirrs as if turning to face Pleck] Yes? PLECK: What species is Dar? C-53: Ambassador Decksetter, I believe you just asked Dar whether you could ask her a personal question. PLECK: [very quietly] You don’t need-- you can just keep quiet-- C-53: And she responded in the negative. PLECK: Okay. That’s-- yep. C-53: I would feel I was invading her privacy to reveal that information. PLECK: Okay, yeah. No, we don’t need to talk-- I get that now. We don’t need to talk-- I was just curious. C-53: Very well. PLECK: [clears throat] Hey, Bargie? BARGIE: No. PLECK: [laughs] No, I’m not gonna-- I would not-- I get it, we’re not, I’m-- C-53: [moderately amused] But were you about to ask? PLECK: That doesn’t-- that’s irrelevant at this point. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 1345736 Musicals often demonstrate the cultural aspects of the periods in which they were written Dowd, James M., M.A. The American University, 1991 Copyright ©1991 by Dowd, James M. -

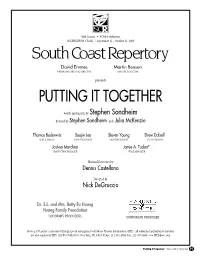

Putting It Together

46th Season • 437th Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / September 11 - October 11, 2009 David Emmes Martin Benson Producing ArtiStic director ArtiStic director presents PUTTING IT TOGETHER words and music by Stephen Sondheim devised by Stephen Sondheim and Julia McKenzie Thomas Buderwitz Soojin Lee Steven Young Drew Dalzell Scenic deSign coStume deSign Lighting deSign Sound deSign Joshua Marchesi Jamie A. Tucker* Production mAnAger StAge mAnAger musical direction by Dennis Castellano directed by Nick DeGruccio Dr. S.L. and Mrs. Betty Eu Huang Huang Family Foundation honorAry ProducerS corPorAte Producer Putting It Together is presented through special arrangement with music theatre international (mti). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by mti. 421 West 54th Street, new york, ny 10019; Phone: 212-541-4684 Fax: 212-397-4684; www.mtiShows.com Putting It Together• SOUTH COA S T REPE R TO R Y P1 THE CAST (in order of appearance) Matt McGrath* Harry Groener* Niki Scalera* Dan Callaway* Mary Gordon Murray* MUSICIANS Dennis Castellano (conductor/keyboards), John Glaudini (synthesizer), John Reilly (woodwinds), Louis Allee (percussion) SETTING A New York penthouse apartment. Now. LENGTH Approximately two hours including one 15-minute intermission. PRODUCTION STAFF Casting ................................................................................ Joanne DeNaut, CSA Dramaturg .......................................................................... Linda Sullivan Baity Assistant Stage Manager ............................................................. -

Worldpeaceoneaçom

A D V E R T I S E M E N T ito EXPERIENCE THE BUZZ FEB 9 _ - ----.. wor .. ' hRD:llwww.worWpeaceorle.coml--. yrniMall. 1A.4 . taunt NaaN1eM m ._ .. .. .. fall yew -Magness on_.. .Mar Vector ... eeay yahoo, V/orld ® old boo... Newr Apple Apppe. 1Sa1- Peace ^ q - . .. PIRChif... AAmazor, - - - -- q GVer S.- 1G Cuogle ... O S1T1( ' Direcur.._ fashM (a leanvau cena WORLD PEACE ® Worla. A ONE - TEN TEN YEAR GLOBAL PEACE INITIATIVE rF;f!L 10 ANNUAL CLOUM. CONC,F.Ftr OROAOCASTS 10 ANNUAL WORLD PEACE SYMPOSIA 10 OLOLAE AMUASSAOOR GENERALS Portugal issues CLAES NOBEL First WPI Joins World Peace One cad more Stamp and Race Artivist DOUG 1VANOV{CN Eiletime Award WP1's Founder and Executive see vedee. Producer tens us why humanity must barn, an end to war, before war brings an end b humanity. , CHINA GOVERNMENT COMMITS tc TO WORLD PEACE ONE CONCERT ligillillrrllr.s``.111 NAM UNVEILS- 1 - YEAR PORTUGAL JOINS .GLBALINITtATIVE WORLD PEACE ONE CONCERT PEACE TALKS Pateec Swayze Cheftrna Applegate Brian McKnight Taylor Dane ONE UiarY P00111 O.elbìYSa bald IMPS IfaaRei Pews Award Welcome co WPt 000P0«'O www.billboard.com www.billboard.biz US $6.99 CAN $8.99 UK £5.50 WorldPeaceOneaçom k I3XNCTCC SCH 3 -DIGIT 907 913L24080439 MAR08 REG A04 000 /004 $6.99US $8 99CAN 06> I IIlu liii ilIIIIIIiiiIiiiIiiIIiiIIIIIIIllliIilllllll MONTY GREENLY 0028 3740 ELM AVE t A LONG BEACH CA 90807 -3402 001164 i i o 89 47205 9 World Peace One invites you to launch a World Movement whose intent is nothing less than to secure the future of the entire Human Race. -

Desperate Housewives a Lot Goes on in the Strange Neighborhood of Wisteria Lane

Desperate Housewives A lot goes on in the strange neighborhood of Wisteria Lane. Sneak into the lives of five women: Susan, a single mother; Lynette, a woman desperately trying to b alance family and career; Gabrielle, an exmodel who has everything but a good m arriage; Bree, a perfect housewife with an imperfect relationship and Edie Britt , a real estate agent with a rocking love life. These are the famous five of Des perate Housewives, a primetime TV show. Get an insight into these popular charac ters with these Desperate Housewives quotes. Susan Yeah, well, my heart wants to hurt you, but I'm able to control myself! How would you feel if I used your child support payments for plastic surgery? Every time we went out for pizza you could have said, "Hey, I once killed a man. " Okay, yes I am closer to your father than I have been in the past, the bitter ha tred has now settled to a respectful disgust. Lynette Please hear me out this is important. Today I have a chance to join the human rac e for a few hours there are actual adults waiting for me with margaritas. Loo k, I'm in a dress, I have makeup on. We didn't exactly forget. It's just usually when the hostess dies, the party is off. And I love you because you find ways to compliment me when you could just say, " I told you so." Gabrielle I want a sexy little convertible! And I want to buy one, right now! Why are all rich men such jerks? The way I see it is that good friends support each other after something bad has happened, great friends act as if nothing has happened. -

Ebook Download Soul Virgins Redefining Single Sexuality 1St

SOUL VIRGINS REDEFINING SINGLE SEXUALITY 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Doug Rosenau | --- | --- | --- | 9780985810719 | --- | --- Soul Virgins Redefining Single Sexuality 1st edition PDF Book Perspectives switch, and the narrator inhabits Septimus Warren Smith, a World War I veteran suffering from shell shock what today would likely be identified as post-traumatic stress disorder , or PTSD. The authors place the responsibility back on readers and therefore do not expect them to merely follow a set of I really enjoyed this book. The insert displays just a small amount ofwear or age with a few light spots of foxing, whilst the vinyl remains excellent with only a few surface scuffs. This copy is still factory sealed from new in the original shrink leaving it Mint and unplayed - a real collector's copy! Though probably incomplete, the poem is widely considered the best epic poem of the Silver Age of Latin literature. American historian and bible scholar, Richard Carrier writes: One could say that Jesus was an insignificant, illiterate, itinerant preacher with a tiny following, who went wholly unnoticed by any literate person in Judaea. Whether currently single again, never married, divorced or widowed, every follower of Christ makes a "pledge of soul virginity" for a lifetime. See 'More Info' for further details of this great Stones rarity! He was the tutor and later, an advisor to emperor Nero. Within the coupling stage, the authors describe four essential steps:. Perfectforthe well versed completist or a new casual fan to pick up the lot in one swoop!! The sleeve displays only light wear nd the disc has some light cosmetic marks, overall an excellent example. -

Title "Stand by Your Man/There Ain't No Future In

TITLE "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC by S. DIANE WILLIAMS Presented to the American Culture Faculty at the University of Michigan-Flint in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Liberal Studies in American Culture Date 98 8AUGUST 15 988AUGUST Firs t Reader Second Reader "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC S. DIANE WILLIAMS AUGUST 15, 19SB TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Introduction - "You Never Called Me By My Name" Page 1 Chapter 1 — "Would Jesus Wear A Rolen" Page 13 Chapter 2 - "You Ain’t Woman Enough To Take My Man./ Stand By Your Man"; Lorrtta Lynn and Tammy Wynette Page 38 Chapter 3 - "Think About Love/Happy Birthday Dear Heartache"; Dolly Parton and Barbara Mandrell Page 53 Chapter 4 - "Do Me With Love/Love Will Find Its Way To You"; Janie Frickie and Reba McEntire F'aqe 70 Chapter 5 - "Hello, Dari in"; Conpempory Male Vocalists Page 90 Conclusion - "If 017 Hank Could Only See Us Now" Page 117 Appendix A - Comparison Of Billboard Chart F'osi t i ons Appendix B - Country Music Industry Awards Appendix C - Index of Songs Works Consulted PREFACE I grew up just outside of Flint, Michigan, not a place generally considered the huh of country music activity. One of the many misconception about country music is that its audience is strictly southern and rural; my northern urban working class family listened exclusively to country music. As a teenager I was was more interested in Motown than Nashville, but by the time I reached my early thirties I had became a serious country music fan. -

Desperate Housewives

Desperate Housewives Titre original Desperate Housewives Autres titres francophones Beautés désespérées Genre Comédie dramatique Créateur(s) Marc Cherry Musique Steve Jablonsky, Danny Elfman (2 épisodes) Pays d’origine États-Unis Chaîne d’origine ABC Nombre de saisons 5 Nombre d’épisodes 108 Durée 42 minutes Diffusion d’origine 3 octobre 2004 – en production (arrêt prévu en 2013)1 Desperate Housewives ou Beautés désespérées2 (Desperate Housewives en version originale) est un feuilleton télévisé américain créé par Charles Pratt Jr. et Marc Cherry et diffusé depuis le 3 octobre 2004 sur le réseau ABC. En Europe, le feuilleton est diffusé depuis le 8 septembre 2005 sur Canal+ (France), le 19 mai sur TSR1 (Suisse) et le 23 mai 2006 sur M6. En Belgique, la première saison a été diffusée à partir de novembre 2005 sur RTL-TVI puis BeTV a repris la série en proposant les épisodes inédits en avant-première (et avec quelques mois d'avance sur RTL-TVI saison 2, premier épisode le 12 novembre 2006). Depuis, les diffusions se suivent sur chaque chaîne francophone, (cf chaque saison pour voir les différentes diffusions : Liste des épisodes de Desperate Housewives). 1 Desperate Housewives jusqu'en 2013 ! 2La traduction littérale aurait pu être Ménagères désespérées ou littéralement Épouses au foyer désespérées. Synopsis Ce feuilleton met en scène le quotidien mouvementé de plusieurs femmes (parfois gagnées par le bovarysme). Susan Mayer, Lynette Scavo, Bree Van De Kamp, Gabrielle Solis, Edie Britt et depuis la Saison 4, Katherine Mayfair vivent dans la même ville Fairview, dans la rue Wisteria Lane. À travers le nom de cette ville se dégage le stéréotype parfaitement reconnaissable des banlieues proprettes des grandes villes américaines (celles des quartiers résidentiels des wasp ou de la middle class). -

Developmental Cross Training Repertoire for Musical Theatre

Developmental Cross Training Repertoire for Musical Theatre Women The repertoire suggestions below target specific developmental goals. It is important to keep in mind however that the distinguishing characteristic of musical theatre singing is the variability of tonal resonance within any given song. A predominantly soprano song might suddenly launch into a belt moment. A chest dominant ballad may release into a tender soprano. Story always pre-empts musical choices. “Just You Wait” from My Fair Lady is part of the soprano canon but we would be disappointed if Eliza could not tell Henry Higgins what she really felt. In order to make things easier for beginning students, it’s a good idea to find repertoire with targeted range and consistent quality as students develop skill in coordinating registration. Soprano Mix—Beginner, Teens to Young Adult Examples of songs to help young sopranos begin to feel functionally confident and enthusiastic about characters and repertoire. Integrating the middle soprano is a priority and it is wise to start there. My Ship Lady in the Dark Weill Far from the Home I Love Fiddler on the Roof Bock/ Harnick Ten Minutes Ago Cinderella Rodgers/Hammerstein Mr. Snow Carousel Rodgers/Hammerstein Happiness is a Thing Called Joe Cabin in the Sky Arlen/Harburg One Boy Bye Bye Birdie Strouse/Adams Dream with Me Peter Pan Bernstein Just Imagine Good News! DeSylva/Brown So Far Allegro Rodgers/Hammerstein A Very Special Day Me and Juliet Rodgers/Hammerstein How Lovely to be a Woman Bye Bye Birdie Strouse/Adams One Boy Bye Bye Birdie Strouse/Adams Lovely Funny Thing. -

George Furth

AND Norma and Sol Kugler PRESENT MUSIC & LYRICS BY Stephen Sondheim BOOK BY George Furth STARRING Aaron Tveit AND Jeannette Bayardelle Mara Davi Josh Franklin Ellen Harvey Rebecca Kuznick Kate Loprest James Ludwig Lauren Marcus Jane Pfitsch Zachary Prince Peter Reardon Nora Schell Lawrence E. Street SCENIC DESIGNER COSTUME DESIGNER LIGHTING DESIGNER SOUND DESIGNER Kristen Robinson Sara Jean Tosetti Brian Tovar Ed Chapman HAIR & WIG DESIGNER PRODUCTION STAGE MANAGER CASTING Liz Printz Renee Lutz Pat McCorkle, Katja Zarolinski, CSA BERKSHIRE PRESS REPRESENTATIVE NATIONAL PRESS REPRESENTATIVE Charlie Siedenburg Matt Ross Public Relations MUSIC SUPERVISION BY MUSICAL DIRECTION BY Darren R. Cohen Dan Pardo CHOREOGRAPHED BY Jeffrey Page DIRECTED BY Julianne Boyd Sponsored in part by Carrie and David Schulman COMPANY is presented through a special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI). ORIGINALLY PRODUCED AND DIRECTED ON BROADWAY BY Harold Prince ORCHESTRATIONS BY Jonathan Tunick BOYD-QUINSON MAINSTAGE AUGUST 10—SEPTEMBER 10, 2017 TIME & PLACE 1970's New York City, Robert’s 35th birthday. CAST IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE Robert .....................................................................................................Aaron Tveit* Susan ...................................................................................................Kate Loprest* Peter ....................................................................................................Josh Franklin* Sarah ........................................................................................Jeannette