Improving Governance and Scaling up Poverty Reduction Through CBMS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commission on Elections Certified List of Overseas

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS OFFICE FOR OVERSEAS VOTING CERTIFIED LIST OF OVERSEAS VOTERS (CLOV) (LANDBASED) Country : UNITED ARAB EMIRATES Post/Jurisdiction : ABU DHABI Source: Server Seq. No Voter's Name Registration Date 53651 JABAGAT, EMILY OÑOT September 27, 2015 53652 JABAGAT, GELTHA SACAY January 22, 2018 53653 JABAGAT, JERWIN GUERRA September 03, 2014 53654 JABAGAT, MELDIE CACHO October 16, 2014 53655 JABAJAB, JAYSON HAMOROLIN December 04, 2017 53656 JABAL, ARVEE LUZ TABAO October 27, 2014 53657 JABALDE, GRACE ESPINO March 03, 2015 53658 JABALON, RONDEC BUGAWAN May 21, 2018 53659 JABAN, JENALIE ALCALDE April 02, 2017 53660 JABAO, HONEYBEE GALENDEZ August 03, 2014 53661 JABAO, JAMES IAN GALENDEZ October 09, 2014 53662 JABAO, RIECEL PATRIA July 16, 2017 53663 JABAT, ELJANE JAWILI May 18, 2012 53664 JABAT, ELWARD JAWILI June 11, 2015 53665 JABAT, TESSIE ALFANTE June 11, 2015 53666 JABEL, JEROME VIRTUCIO September 19, 2017 53667 JABELLO, ISMAEL JR. CRUZ December 22, 2014 53668 JABERINA, GRACE JASA August 13, 2015 53669 JABIGUIRO, SUSAN RARA June 21, 2015 53670 JABILLES, LIGAYA QUILLOBE November 20, 2017 53671 JABILLES, PRIMO IV RESTOR September 18, 2018 53672 JABINES, ALLAN OLMILLA April 30, 2012 53673 JABINES, CHRISTOPHER QUITALIG January 19, 2015 53674 JABINES, MELONIE SAJOL October 24, 2017 53675 JABINES, RAJAIAH BITANG May 18, 2012 53676 JABINES, RITCHE ANN GIL March 08, 2018 53677 JABINEZ, MERY MADALENE BELLA October 28, 2012 53678 JABINIGAY, EDEHLEN FAITH JORDAN August 27, 2015 53679 JABLO, MARIA FE SOMBILON July 10, 2014 NOTICE: All authorized recipients of any personal data, personal information, privileged information and sensitive personal information contained in this document. -

WBCP 2Nd Newsletter

Volume 2, Issue 1 Wild about Birds 14 January 2006 Newsletter of the Wild Bird Club of the Philippines WBCP flies high with the First Philippine Bird Festival By Trinket Canlas Inside this issue: “Phenomenal. A huge success.” This was the overwhelming evaluation of the first-ever WBCP flies Philippine Bird Festival. Organized by the Wild Bird Club of the Philippines (WBCP) and its high with the 1 Festival Committee, the one-day Festival was held on 18 November 2005 at the Crossroad First Philippine 77 Convenarium at Mother Ignacia Avenue in Quezon City. Bird Festival With its theme, “A Voyage of Discovery”, the Festival aimed at highlighting the country’s The Festival in wealth of bird life and raising conservation awareness through the promotion of bird 2 watching and the responsible appreciation of nature. It featured information and display pictures booths set up by environmental and community development organizations and WBCP is government agencies, photo and art exhibits, educational animal and bird shows, film showings, lectures, and children’s activities such as face-painting, drawing, origami and honorary OBC 3 colouring. member Highlights from Cutting the ribbon to start the festivities were WBCP President Michael Lu, Festival 4 Committee Chairperson Alice Villa-Real, Ricky de Castro of Mirant Philippines Foundation the field (the Foundation was the Festival’s main sponsor), and Bataan Congressman Albert Garcia. The opening program hosted by Anna Maria Gonzales included a keynote speech by Tim WBCP Fisher, one of the authors of the Guide to the Birds of the Philippines and WBCP member. endorses 6 Principles of More than a thousand students flocked to the Convenarium to take part in Festival activities. -

Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014

This event is dedicated to the Filipino People on the occasion of the five- day pastoral and state visit of Pope Francis here in the Philippines on October 23 to 27, 2014 part of 22- day Asian and Oceanian tour from October 22 to November 13, 2014. Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 ―Mercy and Compassion‖ a Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014 Contents About the project ............................................................................................... 2 About the Theme of the Apostolic Visit: ‗Mercy and Compassion‘.................................. 4 History of Jesus is Lord Church Worldwide.............................................................................. 6 Executive Branch of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Vice Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines .............................................................. 16 Speaker of the House of Representatives of the Philippines ............................................ 16 Presidents of the Senate of the Philippines .......................................................................... 17 Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines ...................................................... 17 Leaders of the Roman Catholic Church ................................................................ 18 Pope (Roman Catholic Bishop of Rome and Worldwide Leader of Roman -

Corona Impeachment Trial Momblogger, Guest Contributors, Press Releases, Blogwatch.TV

Corona Impeachment Trial momblogger, Guest Contributors, Press Releases, BlogWatch.TV Creative Commons - BY -- 2012 Dedication Be in the know. Read the first two weeks of the Corona Impeachment trial Acknowledgements Guest contributors, bloggers, social media users and news media organizations Table of Contents Blog Watch Posts 1 #CJTrialWatch: List of at least 93 witnesses and documentary evidence to be presented by the Prosecution 1 #CJtrialWatch DAY 7: Memorable Exchanges, and One-Liners, AHA AHA! 10 How is the press faring in its Corona impeachment trial coverage? via @cmfr 12 @senmiriam Senator Santiago lays down 3 Crucial Points for the Impeachment Trial 13 How is the press faring in its Corona impeachment trial coverage? via @cmfr 14 Impeachment and Reproductive Health Advocacy: Parellelisms and Contrasts 14 Impeachment Chronicles, 16-19 January 2012 (Day 1-4) via Akbayan 18 Dismantling Coronarroyo, A Conspiracy of Millions 22 Simplifying the Senate Rules on Impeachment Trials 26 Statement of Assets, Liabilities and Net Worth (SALN) 36 #CJTrialWatch: Your role as Filipino Citizens 38 Video & transcript: Speech of Chief Justice Renato Corona at the Supreme Court before trial #CJtrialWatch 41 A Primer on the New Rules of Procedure Governing Impeachment Trials in the Senate of the Philippines 43 Making Sacred Cows Accountable: Impeachment as the Most Formidable Weapon in the Arsenal of Democracy 50 List of Congressmen Who Signed/Did Not Sign the Corona Impeachment Complaint 53 Twitter reactions: House of Representatives sign to impeach Corona 62 Full Text of Impeachment Complaint Against Supreme Court Chief Justice Renato Corona 66 Archives and Commentaries 70 Corona Impeachment Trial 70 Download Reading materials : Corona Impeachment trial 74 Blog Watch Posts #CJTrialWatch: List of at least 93 witnesses and documentary evidence to be presented by the Prosecution Blog Watch Posts #CJTrialWatch: List of at least 93 witnesses and documentary evidence to be presented by the Prosecution Lead prosecutor Rep. -

LPP EASE of DOING BUSINESS FORUM “RA 11032: LEADING the Lgus TOWARDS

Coordinating Office: Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (KAS) 5th Floor, Cambridge Center Building, 108 Tordesillas cor. Gallardo St. Salcedo Village, Makati City 1227, Metro Manila, Philippines Tels.: +63 (2) 894 37 37 | Fax: +63 (2) 893 61 99 www.logic-philippines.com LoGIC- LPP EASE OF DOING BUSINESS FORUM “R.A. 11032: LEADING THE LGUs TOWARDS EFFICIENT GOVERNMENT SERVICE DELIVERY” Ballroom, Diamond Hotel, Roxas Boulevard, Manila|October 17, 2019 | 9:00AM-5:00PM 9:00 AM Registration 09:30 AM Call to Order 09:45 AM Welcome Message Ms. Stephanie Carette Program Manager European Union Delegation Hon. Presbitero J. Velasco, Jr. National President, LPP Governor, Province of Marinduque 10:00 AM Keynote Message Dir. Atty. Jeremiah B. Belgica Director General, ARTA 10:15 AM Highlights of the Seal of Good Local Governance (SGLG) Act Hon. Jose Enrique S. Garcia III Congressman, Bataan 2nd District 10:30 AM Forum on Ease of Doing Business with NGAs - EoDB at a glance, ARTA as its prime mover - Atty. Ernesto V. Perez, Deputy Director General, ARTA - EoDB on Competitiveness and Negosyo Center Asec. Mary Jean Pacheco, Asst. Secretary, DTI- CB - Public Servant’s take on EoDB Dir. Ma. Luisa Agamata, Director, CSC-PAIO - The SGLG Law and its Relevance to Making the Doing of Business Easier and Public Service Delivery Effective in LGUs Atty. Odilon L. Pasaraba, Director, BLGS-DILG 11:30 AM Open Forum This project is co-funded Implemented by the consortium Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (KAS), the European Chamber of Commerce of the Philippines (ECCP), Centrist Democratic Political by the European Union (EU) Institute (CDPI), League of Cities of the Philippines (LCP), League of Municipalities of the Philippines (LMP) and League of Provinces of the Philippines (LPP). -

Republic of the Philippines REGION VIII As of July 2020 Biliran Grace J. Casil DIRECTORY of PROVINCIAL/CITY/MUNICIPAL NUTRITION

Republic of the Philippines Department of Health NATIONAL NUTRITION COUNCIL DIRECTORY OF PROVINCIAL/CITY/MUNICIPAL NUTRITION ACTION OFFICERS REGION VIII as of July 2020 PROVINCE/CITY/ LOCAL CHIEF EXECUTIVE P/C/MNAO E-MAIL ADDRESS MUNICIPALITY Dr. Edgar Veloso (PNAO) [email protected] Biliran Rogelio J. Espina (Governor) Rio Rosales (DNPC) [email protected] Almeria Richard D. Jaguros Dr. Evelyn Garcia [email protected] Biliran Grace J. Casil Lemuel Antonio Cabucgayan Marisol A. Masbang Dr. Julieta Tan Rhodessa D. Revita Dr. Dionesio Plaza [email protected]/ [email protected] Caibiran Culaba Humphrey B. Olimba Dr. Estrella Pedrosa Kawayan Rodolfo J. Espina, Sr. Dr. Christine Balasbas [email protected]/ Joseph C. Caingcoy Dr. Kezia Lois Arcolas Maripipi [email protected] Naval Gerard Roger M. Espina Dr. Fernando B. Montejo [email protected] PROVINCE/CITY/ LOCAL CHIEF EXECUTIVE P/C/MNAO E-MAIL ADDRESS MUNICIPALITY Estela Therese De Guzman [email protected] (PNAO) Leyte Leopoldo Dominico L. Petilla (Governor) Rowena Bertulfo (DNPC) Ma. Ferlin A. Martinez (DNPC) Lemar Mercader (DNPC) Abuyog Lemuel Gin K. Traya Ma. Fatima P. Garde [email protected] Alangalang Lovell Anne M. Yu Loreza O. Burzon [email protected] [email protected]/ Sixto B. Dela Victoria Maria Hazel C. Barte Albuera [email protected] [email protected]/ Maria Fe G. Rondina Nenita M. Cachero Babatngon [email protected] Barugo Ma. Rosario C. Avestruz Wina Castroverde [email protected] [email protected]/ Nathaniel B. Gertos Cristine A. Coco Bato [email protected] Burauen Juanito E. Renomeron Ma. Queena Serrano [email protected] Calubian Marciano A. Batiancela, Jr. -

AP-BORROWER for Posting to Pag-IBIG Website.Xlsx

NAME 45 ABASOLA, JACQUELYN GRANIL 46 ABASTA, ELEANOR GUTIERREZ 47 ABASTA, JOEL DALUSONG 48 ABASTA JR, SANCHO AGOSTOSA 49 ABASTILLAS, JAY Q 50 ABASULA, NOEL STA MARIA 51 ABAT, DARLENE TABU 52 ABATAS, QUINTIN DELOS SANTOS 53 ABAUAG, MARICEL CABERO 54 ABAYA, CYRENE DARADAL 55 ABAYA, MARIA ELISA BATAC 56 ABAYAN, RYAN VERONA 57 ABAYARE, DEBBIE GAN 58 ABDON, CORAZON NERISSA MILLADO 59 ABDON, DALISAY JOSAFAT 60 ABDRES, JIHNDERICK BALINGIT 61 ABE, LEILANIE DEL ROSARIO 62 ABEDOZA, EDELWINA ANDAYA 63 ABEJAR, JOHN CARREON 64 ABEJAR, RACQUEL ROQUE 65 ABEJO, JAY MARK MANALO 66 ABEJON, RODELIO MINIMO 67 ABELA, EMILYN GARCIA 68 ABELA, NESTOR SUGUE 69 ABELADO, RICKY DELOS REYES 70 ABELLA, ADRIAN CALDERON 71 ABELLA, JOSIE ARAGON 72 ABELLA, LEONARDO CALIMAG 73 ABELLA, LEONILO TALISAY 74 ABELLAR, MA CECILIA RAMOS 75 ABELLERA, ARNIE GALERA 76 ABELLERA JR, ROMEO COCHONGCO 77 ABELLO, DEBORAH CUA 78 ABELLO, EDGARDO GASPAR 79 ABELLO, LAWRENCE SUBA 80 ABELLO, ROSALIE SANTOS 81 ABELON JR, GUILLERMO ALMAZAN 82 ABENIDO, JOJIE SANCHEZ 83 ABERIN, ARNOLD ADRIANO 84 ABERIN, ELENA SEBASTIAN 85 ABERIN, JIMMY GAPUZ 86 ABERIN III, CONRADO MADRID 87 ABERIO JR, TEODORO CASTILLO 88 ABES, CYNTHIA EXALTACION 89 ABES, OFELIA MARGALLO 90 ABESAMIS, GLENN BALMES 91 ABIA, IRENE FAJARDO 92 ABIERA, MARIEL VILLAPANA Page 2 of 412 NAME 93 ABIERTAS, AGNES STA ANA 94 ABIGAN JR, GREGORIO LOQUISAN 95 ABILLE, EMILYN CUNA 96 ABINAL, RIZA MACALINO 97 ABING, ESTHER FAILANO 98 ABIO, CLIFF FORMALEJO 99 ABIOG, ASTERIA BUETA 100 ABIOG, WILFREDO REYES 101 ABION, NESTOR MABELIN 102 ABISTADO, ASTRA -

KABALITA Resilience of a Free Press in All Platforms Is Integral to the Free Flow of Information in the Wake of the Global Pandemic

ISSUE NO. 3872 JUNE 17, 2021 KABALITA Resilience of a free press in all platforms is integral to the free flow of information in the wake of the global pandemic. While many have withered under the pandemic storm, there are media entities that continue to hold fort in the name of fearless reporting. This is the essence of love of country where freedom of the press reigns supreme, a recognition that serves as a lasting legacy. Indeed, when the newsmakers make the news, they make history. www.rcmanila.org TABLE OF CONTENTS PROGRAM TIMETABLE 03 MANILA ROTARIAN IN FOCUS 48 STAR Rtn. Teddy Kalaw, IV THE HISTORY OF THE ROTARY 06 CLUB OF MANILA BASIC EDUCATION AND JOURNALISM AWARDS 55 LITERACY 27 PRESIDENT'S CORNER COMMUNITY ECONOMIC Robert “Bobby” Lim Joseph, Jr. 57 DEVELOPMENT 28 THE WEEK THAT WAS 58 INTERNATIONAL SERVICE CLUB ADMINISTRATION 32 From the Programs Committee 60 INTERCLUB RELATIONS Programs Committee Holds Meeting Attendance THE ROTARY FOUNDATION List of Those Who Have Paid Their 62 Annual Dues Know your Rotary Club of Manila ROTARY INFORMATION Constitution, By-Laws and Policies 63 Rotary Youth Leadership Awards Board of Directors of the Rotary Club of Manila for RY 2020-2021 Holds 25th Special Meeting 65 OTHER MATTERS Board of Directors of the Rotary Club Quotes on Life by PP Frank Evaristo of Manila for RY 2021-2022 Holds Second Planning Meeting 66 ROTARY CLUB OF MANILA BOARD OF DIRECTORS AND RCMANILA FOUNDATION, INC. EXECUTIVE OFFICERS, 39 RY 2020-2021 40 VOCATIONAL SERVICE RCM BALITA EDITORIAL TEAM, RY 2020-2021 46 COGS IN THE WHEEL Rotary Club of Manila Newsletter balita June 17, 2021 02 Zoom Weekly Membership Luncheon Meeting Pro Patria Journalism Awards 2021 Rotary Year 2020-2021 Thursday, June 17, 2021, 12:30 PM PROGRAM TIMETABLE 11:30 AM Registration and Zoom In Program Moderator/Facilitator/ChikaTalk Rtn. -

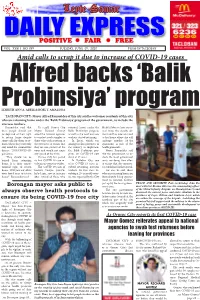

LSDE June 09, 2020

Leyte-Samar DAILYPOSITIVE EXPRESS l FAIR l FREE VOL. XXXI I NO. 049 TUESDAY, JUNE 09, 2020 P15.00 IN TACLOBAN Amid calls to scrap it due to increase of COVID-19 cases Alfred backs ‘Balik Probinsiya’LIZBETH ANN A. ABELLA/ROEL T. AMAZONA program TACLOBAN CITY- Mayor Alfred Romualdez of this city said he welcomes residents of this city who are returning home under the ‘Balik Probinsiya’ program of the government, to include the overseas workers. Romualdez said that To recall, Ormoc City returned home under the Health Office to have recov- these people should not Mayor Richard Gomez Balik Probinsiya program ered from the deadly ail- be deprived of their right asked the national agencies as well as the local overseas ment and has now returned to return home despite to conduct swab samples to workers started returning. to her home where she will some calls for them to re- those who wish to return to In Leyte, which was undergo another 14-day main where they currently the provinces to ensure that among the first provinces of quarantine as part of the stay amid the coronavirus they are not carriers of the the country to implement health protocols. disease 2019(COVID-19) virus and would not cause the Balik Probinsya pro- Mayor Romualdez said pandemic. any spread of the virus. gram, its COVID-19 now that the government, to in- “They should not be Ormoc City has posted stand at 17 cases. clude the local government barred from returning its first COVID-19 case in- In Tacloban City, two units, are doing their effort home. -

Download PDF File

Subic bay news vol 13 no 48 20.00Php Tapas Bar and Restaurant 2nd Floor Subic Gas Bldg 724, Dewey Avenue, Subic Bay Freeport Zone Bataan now red tide free CITY OF SAN FERNANDO, Pampanga – The Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Re- sources (BFAR) has declared Bataan free of the deadly red tide toxin and lifted the shellfish ban it imposed last Oct. 19. BFAR regional director Wilfredo Cruz said on Wednesday the latest shell- fish bulletin declared the absence of red tide in the coastal waters of Bataan after laboratory tests showed negative results of the toxin from samples drawn from the areas. Red tide toxin causes paralytic shellfish poisoning with symptoms in- cluding abdominal cramps, vomiting, diarrhea, and numbness in the face and arms. With the lifting of the ban, Cruz said that harvesting, transporting, selling and eating of shellfish from the coastal areas of Bataan are no longer prohibited. Cruz welcomed the develop- ment, saying he was happy that finally, those dependent on shellfish for their livelihood can now heave a sigh of relief. “Region 3 is red tide-free. Res- idents can now eat tahong (green mus- sels), talaba (oyster), and other shellfish from Bataan,” he said in a statement. SM GROUP BRINGS CHRISTMAS JOY THROUGH KALINGA DONATION DRIVE. Aeta residents from Maliwakat Tribe Brgy. (PNA) New Cabalan were among the recipients of SM Christmas Kalinga packs. (story on page 2) Here's to better times in the coming year! God Bless Us All! Season's greetings from yourSubic Bay News Family! Agri-business hub to rise in New Clark City NEW CLARK CITY, Tarlac -- Department of and mini-seed production farms that will Agriculture (DA) inked a Memorandum of allow the development of all types of seed Agreement with Bases Conversion and De- varieties to ensure access to high-yielding velopment Authority (BCDA) to establish seeds. -

Central Number 23 Mon - Sat April 12-17, 2021 Punto! PANANAW NG MALAYANG PILIPINO! Luzon E-Pray Launched for Healing by Armand M

www.punto.com.ph P 10.00 Volume 14 Central Number 23 Mon - Sat April 12-17, 2021 Punto! PANANAW NG MALAYANG PILIPINO! Luzon E-Pray launched for healing By Armand M. Galang natuan created an online Cabanatuan was the re- because of this experi- platform to attend to spir- sult of their efforts to ence,” referring to the ef- CABANATUAN CITY - itually and physically ill look for ways and means fect of pandemic. Amid the distress brought people. to get in touch with “the “Ito’y isang paanyaya by the pandemic, the Cabanatuan Bishop many of our brothers and para sa ating lahat upa- clergy and the religious Sofronio Bancud said the sisters who truly suffer, ng sa pagkilala natin sa in the Diocese of Caba- ministry called E-Pray who were left desperate Page 9 please Clark execs return new vehicles, villas By Bong Z. Lacson LARK FREEPORT – The Clark Development Corp. said Monday it recalled all service Cvehicles and staff houses issued to its board of directors in response to the Commission on Audit’s report red-flagging the practice. “The CDC manage- sion, a majority of the ment has already ordered board members signified the recall of the vehicles the willingness to lease which will be pooled for the houses themselves so the use of the entire orga- they can continue to have nization, said CDC pres- a safe place to stay when ident-CEO Manuel R. in Clark,” he added. Gaerlan in a statement. In a 2020 audit report “In an executive ses- Page 10 please Mayor EdSa pushes sustainable agriculture CITY OF SAN FER- “EdSa” Santiago has NANDO -- To maintain ordered the intensifi- food security and live- cation of the city gov- lihood opportunities in ernment’s gardening The pictures, taken 3 p.m. -

Official List of Qualifiers for the 2015 Dost-Sei Science

OFFICIAL LIST OF QUALIFIERS FOR THE 2015 DOST - SEI SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY SCHOLARSHIPS The Department of Science and Technology (DOST) through the Science Education Institute (SEI) announces the names of the S&T scholarship qualifiers in 2015. Each qualifier shall receive a notice of award from the DOST-SEI or DOST Regional Office stating the date of orientation and contract signing. He/she shall report at the designated venue with a parent/legal guardian who must bring a 2015 Community Tax Certificate or Passport. The legal guardian is required to submit his/her notarized affidavit of guardianship. The new scholarship awardees must seek admission in any of the priority S&T fields of study at state colleges and universities and CHED-identified Centers of Excellence/Centers of Development. The following are the qualifiers of the DOST-SEI Scholarship Programs: AALA, MARK ARIS GUSTILO ABABA-EN, JEZEBEL FAUSTINO ABAD, CHRIS IVY JAMAICA ALVAREZ ABAD, JUSCEL CERVANTES ABADESA, WENDIE NEPTUNO ABAGGOY, RHYMA ALLIAH BAN-OS ABAL, JOSEPH ALBERT ABAMO, JAMES RYAN RANOCO ABANADOR, TRISHA CLAIRE SERRANO ABANES, MAIAH MARGARET RAFER ABANES, MARUEL BATINGAL ABANILLA, BRIX LAURENCE RICARDOS ABANTAO, FRANCIS ABADIANO ABAO, KATHLYNE GAILE PEREZ ABAO, MARK TECIO ABAO, RHANLEE DIONIO ABAO, SHIELA MAE BELMORES ABARDO, RICA MAYOR ABARQUEZ, CHRISTIAN KATE LOGAGAY ABARQUEZ, JENNY RUEDAS ABARRO, JUNEL - I FLORES ABARSOZA, APRIL LOUISE LOPEZ ABAS, PAUL VINCENT LUMPAYAO ABASOLO, PAMELA JISON ABAY, DAVE SAYOD ABAYAN, JHESTINE MARIELLE MANABAT ABCEDE, DHAENIE VILLE