Bowie's Books

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hugo Hamilton's Berlin Trilogy

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title "Struck with Ireland fever": Hugo Hamilton's Berlin trilogy Author(s) Schrage-Frueh, Michaela Publication Date 2019 Schrage-Frueh, Michaela. (2019). "Struck with Ireland fever": Publication Hugo Hamilton's Berlin trilogy. In Deirdre Byrnes, Jean Information Conacher, & Gisela Holfter (Eds.), Perceptions and perspectives: Exploring connections between Ireland and the GDR. Trier: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier. Publisher Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier Link to publisher's http://www.wvttrier.de/top/beschreibungen/ID1666.html version Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/16391 Downloaded 2021-09-25T05:41:27Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. “Struck by Ireland-Fever”: Hugo Hamilton's Berlin Trilogy Michaela Schrage-Früh Hugo Hamilton is an Irish-German writer best known for his memoir The Speckled People, published in 2003, which offered a poignant account of his own difficult childhood as son of a German mother and Irish father in Dublin in the 1950s and 1960s. However, Hamilton also spent one year living in Berlin in the mid-1970s and many of his observations in his debut novel Surrogate City, published in 1990, shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall, have been based on his experiences during that sojourn and subsequent visits.1 While Surrogate City is set in an unspecified time in pre-unification West Berlin2, with the reality of the Wall and the world beyond it lingering like a shadow in the fringes of the characters’ consciousness, his third novel The Love Test, published in 1995, takes place right after the collapse of the GDR. -

{Download PDF} David Bowie: Starman

DAVID BOWIE: STARMAN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Paul Trynka | 544 pages | 18 Jul 2011 | Little Brown and Company | 9780316032254 | English | London, United Kingdom David Bowie: Starman PDF Book He told me: Let the children lose it Let the children use it Let all the children boogie. Wednesday 8 July Friday 22 May September Glam rock [1]. Tuesday 26 May Song Styles. Archived from the original on 3 November Energetic Happy Hypnotic. Don't want to see ads? The starmen that he is talking about are called the infinites, and they are black-hole jumpers. Thursday 3 September He was a leading figure in the music industry and is… read more. Tuesday 4 August The band thereafter idolised Bowie and subsequently covered " Ziggy Stardust " in The Best Rock Anthems Wednesday 2 September Thursday 14 May Thursday 16 July Various Artists I Love 2 Party Thursday 27 August Saturday 9 May Monday 4 May Song Themes. Tuesday 5 May Monday 29 June Tuesday 20 October Tuesday 8 September Blues Classical Country. Sexy Trippy All Moods. David Bowie: Starman Writer The Singles Collection. With David Bowie there is always a bridge between the past and the future. Thursday 8 October Teenagers, children see Life on Mars , are endowed with much more immediate perception, without the intellectual superstructures typical of the bourgeois England. David Bowie The Singles Collection. The chorus is loosely based on " Over the Rainbow " from the film The Wizard of Oz , alluding to the "Starman"'s extraterrestrial origins over the rainbow the octave leap on "Star- man " is identical to that of Judy Garland 's "some- where " in "Over the Rainbow". -

Classic Albums: the Berlin/Germany Edition

Course Title Classic Albums: The Berlin/Germany Edition Course Number REMU-UT 9817 D01 Spring 2019 Syllabus last updated on: 23-Dec-2018 Lecturer Contact Information Course Details Wednesdays, 6:15pm to 7:30pm (14 weeks) Location NYU Berlin Academic Center, Room BLAC 101 Prerequisites No pre-requisites Units earned 2 credits Course Description A classic album is one that has been deemed by many —or even just a select influential few — as a standard bearer within or without its genre. In this class—a companion to the Classic Albums class offered in New York—we will look and listen at a selection of classic albums recorded in Berlin, or recorded in Germany more broadly, and how the city/country shaped them – from David Bowie's famous Berlin trilogy from 1977 – 79 to Ricardo Villalobos' minimal house masterpiece Alcachofa. We will deconstruct the music and production of these albums, putting them in full social and political context and exploring the range of reasons why they have garnered classic status. Artists, producers and engineers involved in the making of these albums will be invited to discuss their seminal works with the students. Along the way we will also consider the history of German electronic music. We will particularly look at how electronic music developed in Germany before the advent of house and techno in the late 1980s as well as the arrival of Techno, a new musical movement, and new technology in Berlin and Germany in the turbulent years after the Fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, up to the present. -

WATCHMOJO – the Life and Career of David Bowie (1947-2016)

WATCHMOJO – The life and career of David Bowie (1947-2016) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lan_wotkon0 [Fashion] Welcome to watchmojo.com and today we're taking a look at the life and career of David Bowie. [Queen Bitch] David Robert Jones was born on January 8 1947 in Brixton London England. Though he showed musical interest at a young age it was only in the early 60s that he really pursued the art. He started by joining several blues bands but branched off on his own when they had little success. Renaming himself David Bowie he released his self-titled debut in 1967. [Who's that hiding in the apple tree clinging to a branch] Its lack of success led Bowie to participate in a promotional film called Love you till Tuesday which showcased several of his songs. A particular interest was Space Oddity : that track became a hit after it was released at the same time as the first moon landing. [Ground control to Major Tom] His sophomore effort of the same name however was another commercial disappointment. [The man who sold the world] To promote his third album The man who sold the world, Bowie was put in a dress to capitalize on his androgynous look. [Life on mars] [Ziggy Stardust] In 1971 a pop influenced record called Hunky-Dory came out and was followed by the creation of his flamboyant Ziggy Stardust persona and stage show with backing band The Spiders from Mars. Then came his breakthrough record The rise and fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars which climbed the charts thanks to his performance of the single Star Man on Top of the Pops. -

Music & Entertainment Auction

Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Plant (Director) Shuttleworth (Director) (Director) Music & Entertainment Auction 20th February 2018 at 10.00 For enquiries relating to the sale, Viewing: 19th February 2018 10:00 - 16:00 Please contact: Otherwise by Appointment Saleroom One, 81 Greenham Business Park, NEWBURY RG19 6HW Telephone: 01635 580595 Christopher David Martin David Howe Fax: 0871 714 6905 Proudfoot Music & Music & Email: [email protected] Mechanical Entertainment Entertainment www.specialauctionservices.com Music As per our Terms and Conditions and with particular reference to autograph material or works, it is imperative that potential buyers or their agents have inspected pieces that interest them to ensure satisfaction with the lot prior to the auction; the purchase will be made at their own risk. Special Auction Services will give indica- tions of provenance where stated by vendors. Subject to our normal Terms and Conditions, we cannot accept returns. Buyers Premium: 17.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 21% of the Hammer Price Internet Buyers Premium: 20.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 24.6% of the Hammer Price Historic Vocal & other Records 9. Music Hall records, fifty-two, by 16. Thirty-nine vocal records, 12- Askey (3), Wilkie Bard, Fred Barnes, Billy inch, by de Tura, Devries (3), Doloukhanova, 1. English Vocal records, sixty-three, Bennett (5), Byng (3), Harry Champion (4), Domingo, Dragoni (5), Dufranne, Eames (16 12-inch, by Buckman, Butt (11 - several Casey Kids (2), GH Chirgwin, (2), Clapham and inc IRCC20, IRCC24, AGSB60), Easton, Edvina, operatic), T Davies(6), Dawson (19), Deller, Dwyer, de Casalis, GH Elliot (3), Florrie Ford (6), Elmo, Endreze (6) (39, in T1) £40-60 Dearth (4), Dodds, Ellis, N Evans, Falkner, Fear, Harry Fay, Frankau, Will Fyfe (3), Alf Gordon, Ferrier, Florence, Furmidge, Fuller, Foster (63, Tommy Handley (5), Charles Hawtrey, Harry 17. -

Stallings Book 4 Print.Pdf (3.603Mb)

Black Performance and Cultural Criticism Valerie Lee and E. Patrick Johnson, Series Editors Stallings_final.indb 1 5/17/2007 5:14:41 PM Stallings_final.indb 2 5/17/2007 5:14:41 PM Mutha ’ is half a word Intersections of Folklore, Vernacular, Myth, and Queerness in Black Female Culture L. H. Stallings The Ohio State University Press Columbus Stallings_final.indb 3 5/17/2007 5:14:42 PM Copyright © 2007 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Horton-Stallings, LaMonda. Mutha’ is half a word : intersections of folklore, vernacular, myth, and queerness in black female culture / L.H. Stallings. p. cm.—(Black performance and cultural criticism) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1056-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1056-2 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-9135-1 (cd-rom) ISBN-10: 0-8142-9135-X (cd-rom) 1. American literature—African American authors—History and criticism. 2. American literature—women authors—History and criticism. 3. African American women in literature. 4. Lesbianism in literature. 5. Gender identity in literature. 6. African American women— Race identity. 7. African American women—Intellectual life. 8. African American women— Folklore. I. Title. II. Series PS153.N5H68 2007 810.9'353—dc22 2006037239 Cover design by Jennifer Shoffey Forsythe. Cover illustration by Michel Isola from shutterstock.com. Text design and typesetting by Jennifer Shoffey Forsythe in Adobe Garamond. Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. -

The Age of Bowie 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE AGE OF BOWIE 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Paul Morley | 9781501151170 | | | | | The Age of Bowie 1st edition PDF Book His new manager, Ralph Horton, later instrumental in his transition to solo artist soon witnessed Bowie's move to yet another group, the Buzz, yielding the singer's fifth unsuccessful single release, " Do Anything You Say ". Now, Morley has published his personal account of the life, musical influence and cultural impact of his teenage hero, exploring Bowie's constant reinvention of himself and his music over a period of five extraordinarily innovative decades. I think Britain could benefit from a fascist leader. After completing Low and "Heroes" , Bowie spent much of on the Isolar II world tour , bringing the music of the first two Berlin Trilogy albums to almost a million people during 70 concerts in 12 countries. Matthew McConaughey immediately knew wife Camila was 'something special'. Did I learn anything new? Reuse this content. Studying avant- garde theatre and mime under Lindsay Kemp, he was given the role of Cloud in Kemp's theatrical production Pierrot in Turquoise later made into the television film The Looking Glass Murders. Hachette UK. Time Warner. Retrieved 4 October About The Book. The line-up was completed by Tony and Hunt Sales , whom Bowie had known since the late s for their contribution, on bass and drums respectively, to Iggy Pop's album Lust for Life. The Sydney Morning Herald. Morely overwrites, taking a significant chunk of the book's opening to beat Bowie's death to death, the takes the next three-quarters of the book to get us through the mid-Sixties to the end of the Seventies, then a ridiculously few yet somehow still overwritten pages to blast through the Eighties, Nineties, and right up to Blackstar and around to his death again. -

David Bowie Early Years Mp3, Flac, Wma

David Bowie Early Years mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Early Years Country: Europe Released: 1985 Style: Glam, Classic Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1710 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1222 mb WMA version RAR size: 1574 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 303 Other Formats: AAC RA DTS AA VQF WAV DMF Tracklist Hide Credits Aladdin Sane Watch That Man (New York) (R.H.M.S."Ellinis") A1 4:30 Written-By – Bowie* Aladdin Sane (1913-1938-197?) A2 5:15 Written-By – Bowie* Drive-In Saturday (Seattle-Phoenix) A3 4:38 Written-By – Bowie* Panic In Detroit (Detroit) A4 4:30 Written-By – Bowie* Cracked Actor (Los Angeles) A5 3:01 Written-By – Bowie* Time (New Orleans) B1 5:10 Written-By – Bowie* The Prettiest Star (Gloucester Road) B2 3:28 Written-By – Bowie* Let`s Spend The Night Together B3 3:10 Written-By – Jagger/Richards* The Jean Genie (Detroit And New York) B4 4:06 Written-By – Bowie* Lady Grinning Soul (London) B5 3:53 Written-By – Bowie* The Man Who Sold The World The Width Of A Circle C1 8:07 Written-By – David Bowie All The Madmen C2 5:34 Written-By – David Bowie Black Country Rock C3 3:33 Written-By – David Bowie After All C4 3:52 Written-By – David Bowie Running Gun Blues D1 3:12 Written-By – David Bowie Saviour Machine D2 4:27 Written-By – David Bowie She Shook Me Cold D3 4:13 Written-By – David Bowie The Man Who Sold The World D4 3:58 Written-By – David Bowie The Supermen D5 3:39 Written-By – David Bowie Hunky Dory Changes E1 3:34 Written-By – David Bowie Oh Your Pretty Things E2 3:11 Written-By – David Bowie Eight Line Poem E3 2:53 Written-By – David Bowie Life On Mars? E4 3:45 Written-By – David Bowie Kooks E5 2:45 Written-By – David Bowie Quicksand E6 5:03 Written-By – David Bowie Fill Your Heart F1 3:07 Written-By – Rose*, Williams* Andy Warhol F2 3:53 Written-By – David Bowie Song For Bob Dylan F3 4:10 Written-By – David Bowie Queen Bitch F4 3:14 Written-By – David Bowie The Bewlay Brothers F5 5:21 Written-By – David Bowie Companies, etc. -

A Day in the Life of a Maintenance Supervisor

If a problem exists with the work order codes and in- Editors note: We have invited our good friend Maintenance supervisor visits job sites to management Ps ensure no problems exist that will cause formation, the maintenance tech or techs should hold and world-famous author Ricky Smith to write a series planning and a meeting a few minutes before the end of the shift to of articles on a Day in the Life of a... for the various roles in problems with the execution of the main- scheduling ensure the codes are corrected and that the mainte- maintenance reliability. Please e-mail me if you want to write tenance schedule. (Change the time you execute nance tech knows why they need to be changed. about a day in your life at [email protected] this function day to day so your staff does not know your schedule.) Afternoon review of job packages The maintenance supervisor makes his/her rounds to for next day. ensure all work has started on time and no problems The planner/scheduler arrives at the supervisor’s office exist. If personnel are at a remote location, a call on for 10-20 minutes to ensure the job plan for tomorrow the radio or text on the cell at a specific time validates will be executed without a problem. This was talked that either ev- about at the be- erything is on ginning of the schedule, or “we article. have a problem.” A Day in the Life of a Metrics / KPIs While the supervisor is or Dash- making his/her board for rounds they the mainte- should be per- nance team. -

David Bowie's Urban Landscapes and Nightscapes

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 17 | 2018 Paysages et héritages de David Bowie David Bowie’s urban landscapes and nightscapes: A reading of the Bowiean text Jean Du Verger Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/13401 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.13401 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Jean Du Verger, “David Bowie’s urban landscapes and nightscapes: A reading of the Bowiean text”, Miranda [Online], 17 | 2018, Online since 20 September 2018, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/13401 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.13401 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. David Bowie’s urban landscapes and nightscapes: A reading of the Bowiean text 1 David Bowie’s urban landscapes and nightscapes: A reading of the Bowiean text Jean Du Verger “The Word is devided into units which be all in one piece and should be so taken, but the pieces can be had in any order being tied up back and forth, in and out fore and aft like an innaresting sex arrangement. This book spill off the page in all directions, kaleidoscope of vistas, medley of tunes and street noises […]” William Burroughs, The Naked Lunch, 1959. Introduction 1 The urban landscape occupies a specific position in Bowie’s works. His lyrics are fraught with references to “city landscape[s]”5 and urban nightscapes. The metropolis provides not only the object of a diegetic and spectatorial gaze but it also enables the author to further a discourse on his own inner fragmented self as the nexus, lyrics— music—city, offers an extremely rich avenue for investigating and addressing key issues such as alienation, loneliness, nostalgia and death in a postmodern cultural context. -

New and Best-Selling Titles 2015 ‘Reel Art Press Is a Publishing Cult’ ESQUIRE MAGAZINE CONTENTS

New and Best-Selling Titles 2015 ‘Reel Art Press is a publishing cult’ ESQUIRE MAGAZINE CONTENTS Introduction 7 Autumn / Winter 2015 8 Backlist 25 Limited Editions 35 Contact Information 58 One of the greatest pleasures for me when working with artists or their estates is that tantalizing moment, the spark, when a single image, or contact sheet, or long forgotten box of negatives or battered prints promises something special. Diving into the depths of an archive to explore an artist’s brilliance and talent. Our 2015 titles have all given me that unquantifiable moment of excitement when I was certain that something very special could be brought to press and I could not be happier with the resulting editions. My first window into the work of British Magnum photographer David Hurn was in my days as a vintage movie poster dealer, through his work as the special photographer for From Russia With Love and Barbarella. His shots of the stars were the very best of their kind, capturing the icons of the era in all their sixties glamour and cool. Hurn’s photograph of Sean Connery, for example, with his tux and gun in From Russia With Love is one of the most celebrated Bond images of all time, more synonymous with 007 than any other shot. When I began to look more closely at Hurn’s work from the period, one of the things that actually intrigued me most was his non-celebrity work. Hurn is so much more than just another sixties A-list photographer. As Peter Doggett comments in his introduction, “Unlike most of his peers, Hurn delved beyond the fatal attractions of Swinging London and its global counterparts, to pursue his greatest subject: ordinary people pursuing ordinary passions. -

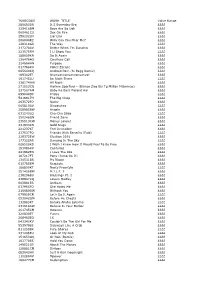

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 289693DR

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 060461CU Sex On Fire ££££ 258202LN Liar Liar ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 217278AV Better When I'm Dancing ££££ 223575FM I Ll Show You ££££ 188659KN Do It Again ££££ 136476HS Courtesy Call ££££ 224684HN Purpose ££££ 017788KU Police Escape ££££ 065640KQ Android Porn (Si Begg Remix) ££££ 189362ET Nyanyanyanyanyanyanya! ££££ 191745LU Be Right There ££££ 236174HW All Night ££££ 271523CQ Harlem Spartans - (Blanco Zico Bis Tg Millian Mizormac) ££££ 237567AM Baby Ko Bass Pasand Hai ££££ 099044DP Friday ££££ 5416917H The Big Chop ££££ 263572FQ Nasty ££££ 065810AV Dispatches ££££ 258985BW Angels ££££ 031243LQ Cha-Cha Slide ££££ 250248GN Friend Zone ££££ 235513CW Money Longer ££££ 231933KN Gold Slugs ££££ 221237KT Feel Invincible ££££ 237537FQ Friends With Benefits (Fwb) ££££ 228372EW Election 2016 ££££ 177322AR Dancing In The Sky ££££ 006520KS I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel To Be Free ££££ 153086KV Centuries ££££ 241982EN I Love The 90s ££££ 187217FT Pony (Jump On It) ££££ 134531BS My Nigga ££££ 015785EM Regulate ££££ 186800KT Nasty Freestyle ££££ 251426BW M.I.L.F. $ ££££ 238296BU Blessings Pt. 1 ££££ 238847KQ Lovers Medley ££££ 003981ER Anthem ££££ 037965FQ She Hates Me ££££ 216680GW Without You ££££ 079929CR Let's Do It Again ££££ 052042GM Before He Cheats ££££ 132883KT Baraka Allahu Lakuma ££££ 231618AW Believe In Your Barber ££££ 261745CM Ooouuu ££££ 220830ET Funny ££££ 268463EQ 16 ££££ 043343KV Couldn't Be The Girl