Arxiv:2007.02217V1 [Quant-Ph] 5 Jul 2020 Irreversible Clocks Such As Radio Carbon Dating and Mach’S Temperature Clock

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Measurement of Time

Measurement of Time M.Y. ANAND, B.A. KAGALI* Department of Physics, Bangalore University, Bangalore 560056 *email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Time was historically measured using the periodic motions of the sun and stars. Various types of sun clocks were devised in Egypt, Greece and Europe. Different types of water clocks were assembled with ever greater accuracy. Only in the seventeenth century did the mechanical clock with pendulums and springs appeared. Accurate quartz clocks and atomic clocks were developed in the first half of the twentieth century. Now we have clocks that have better than microsecond accuracy. This article gives a brief account of all these topics. Keywords: Sun clocks, Water clocks, Mechanical clocks, Quartz clocks, Atomic clocks, World Time, Indian Standard time We all know intuitively what time is. It can be civilizations relied upon the apparent motion of roughly equated with change or motions. From these bodies through the sky to determine the very beginning man has been interested in seasons, months, and years. understanding and measuring time. More We know little about the details of recently, he has been looking for ways to limit timekeeping in prehistoric eras, but we find the “damaging” effects of time and going that in every culture, some people were backward in time! preoccupied with measuring and recording the Celestial bodies—the Sun, Moon, planets, passage of time. Ice-age hunters in Europe over and stars—have provided us a reference for 20,000 years ago scratched lines and gouged measuring the passage of time. Ancient holes in sticks and bones, possibly counting the Physics Education • January − March 2007 277 days between phases of the moon. -

On the Isochronism of Galilei's Horologium

IFToMM Workshop on History of MMS – Palermo 2013 On the isochronism of Galilei's horologium Francesco Sorge, Marco Cammalleri, Giuseppe Genchi DICGIM, Università di Palermo, [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract − Measuring the passage of time has always fascinated the humankind throughout the centuries. It is amazing how the general architecture of clocks has remained almost unchanged in practice to date from the Middle Ages. However, the foremost mechanical developments in clock-making date from the seventeenth century, when the discovery of the isochronism laws of pendular motion by Galilei and Huygens permitted a higher degree of accuracy in the time measure. Keywords: Time Measure, Pendulum, Isochronism Brief Survey on the Art of Clock-Making The first elements of temporal and spatial cognition among the primitive societies were associated with the course of natural events. In practice, the starry heaven played the role of the first huge clock of mankind. According to the philosopher Macrobius (4 th century), even the Latin term hora derives, through the Greek word ‘ώρα , from an Egyptian hieroglyph to be pronounced Heru or Horu , which was Latinized into Horus and was the name of the Egyptian deity of the sun and the sky, who was the son of Osiris and was often represented as a hawk, prince of the sky. Later on, the measure of time began to assume a rudimentary technical connotation and to benefit from the use of more or less ingenious devices. Various kinds of clocks developed to relatively high levels of accuracy through the Egyptian, Assyrian, Greek and Roman civilizations. -

Mini Quartz Clock Movements

Mini Quartz Clock Movements • 10 Year Warranty • Step Second Hand • Dimensions: 2-1/8"W x 2-1/8"H x 5/8"D • Runs on 1 "AA" Size Battery • American "I" Shaft - Diameter 5/16" • Free Set Of Hands and • Front Loading Hanger Mounting Hardware With • Accurate Within 2 Minutes A Year Each Clock Movement • Fits 3" Diameter Hole • Made in USA 1. Drill a 3/8" hole through the material you are working with and insert the movement. 2. Slide brass washer over shaft. 3. Attach dial mounting hex nut. 4. Gently press hour hand onto shaft at 12:00 position. 5. Place minute hand over shaft at 12:00 position. 6. Gently screw minute nut in place. 7. Press on second hand at 12:00 position. 8. Screw on cap nut if no second hand is used. Mini Movements Shaft Length Selecting the Proper Shaft Length Dials B A P r i c e E a c h P e r P k g O f Proper shaft length is important to ensure Stock# up to Thread Total 1 3 10 50 100 sufficient clearance when going through your dial Q-11 1/8" thick 3/16" 17/32" 4.95 4.23 4.45 3.80 4.25 3.63 3.95 3.38 3.75 3.21 board and when using a glass front on your clock. Q-12 1/4" thick 5/16" 5/8" 4.95 4.23 4.45 3.80 4.25 3.63 3.95 3.38 3.75 3.21 Overall Length (A) is measured from the tip of Q-13 3/8" thick 7/16" 3/4" 4.95 4.See23 4.4 website5 3.80 4.25 3for.63 3current.95 3.38 3.75 3.21 the hand shaft to the movement cast. -

Analog Clock Headway Movement FAQS

ANALOG CLOCK HEADWAY MOVEMENT FAQS The links below will work in most PDF viewers and link to the topic area by clicking the link. We recommend Adobe Reader version 10 or greater available at: http://get.adobe.com/reader CONTENTS Analog Clock Headway Movement FAQS .................................................................... 1 Batteries ............................................................................................................................. 2 Atomic Clock Factory Restart ...................................................................................... 2 Supported Time Zones .................................................................................................. 2 Time is Incorrect ............................................................................................................. 2 Clock is incorrect by Hours but minutes are correct .......................................... 3 Daylight Saving Time ..................................................................................................... 3 Manually Set Time ........................................................................................................... 3 How long will the battery last? .................................................................................. 3 Can I shut off the WWVB signal? .............................................................................. 3 Is there a booster antenna to receive the WWVB signal in a difficult location? ............................................................................................................................ -

77A71 Quartz Clock Movement Instructions

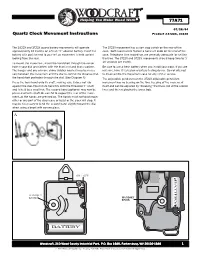

77A71 07/28/94 Quartz Clock Movement Instructions Product #3722X, 3723X The 3622X and 3723X quartz battery movements will operate The 3723X movement has a start-stop switch on the rear of the approximately 12 months on a fresh “C” alkaline battery. Insert the case. Both movements feature a hand set knob on the rear of the battery with positive end to your left as movement is held upright case. Telephone time recordings are generally adequate for setting looking from the rear. the time. The 3722X and 3723X movements should keep time to +/- To mount the movement, insert the handshaft through the center 10 seconds per month. hole in your dial and fasten with the brass nut and brass washer. Be sure to use a fresh battery when you install your clock. If you are The hanger and one or more shims (rubber washer) may be neces- not sure, have it tested on a battery testing device. Do not attempt sary between the movement and the dial to control the distance that to disassemble the movement case for any kind of service. the handshaft protrudes through the dial. (See Diagram A) The adjustable pendulum on the 3722X adjustable pendulum Press the hour hand onto its shaft, making sure it does not rub movement has no bearing on the time keeping of the movement against the dial. The minute hand fits onto the threaded “I” shaft itself and can be adjusted by “breaking” the brass rod at the scored and is held by a small nut. The second hand (optional) may now be lines and then replacing the brass bob. -

Time for a Change?

TIME FOR A CHANGE? Raymond H.V. Gallucci, PhD., P.E.; Frederick, Maryland, USA [email protected] ABSTRACT This work was inspired by Hughes’ book The Binary Universe, which proposes a unique theory about the nature of time and its dominance over phenomena since as gravity and electromagnetic radiation. While Hughes treats time as variable and time dilation as a real phenomenon, I divert while retaining much of Hughes’ proposals to speculate that time is immutable and equivalent to change, albeit progressing at a fixed rate analogous to the fastest proposed by Hughes – the Planck time interval. Keywords: Time (dilation), Planck time, absolute zero, zero point energy, kinetic energy, Bohr hydrogen atom 1. INTRODUCTION In his book The Binary Universe, Hughes strives “to provide a more accurate, simpler and realistic view of relativity and to encourage QM [Quantum Mechanics] physicists to review and re-assess the relationship between QM and the Special and General [Relativity] theories. The book focuses firstly on the macro universe and takes a logical, deductive approach to investigating the nature of space-time and gravity … [W]e focus down to the quantum scale and an in-depth analysis of the nature of time itself is presented … I offer here an alternative theory for gravitation … Finally, … I present the inevitable conclusions about the nature of time and of the universe itself from the Planck scale upwards …” [1] I find much with which to agree in Hughes’ theories, in particular, the following: Time is independent of the physical void since there is no known cause or effect, or suggested mechanism that links the two … Quantum Mechanical Theory recognizes that there is more to the vacuum than simply empty void … Space, the void (or volume), or anything within the void, cannot “exist” without the passage of time. -

Celestial, Flow, and Mechanical Clocks

recalibration Michael A. Lombardi First in a Series on the Evolution of Time Measurement: Celestial, Flow, and Mechanical Clocks ime is elusive. We are comfortable with the concept of us are many centuries older than the first clocks. The first -in time, but in many ways it defies understanding. We struments that we now recognize as clocks could measure T cannot see, hear, or touch time; we can only observe intervals shorter than one day by dividing the day into smaller its effects. Although we are unable to grasp time with our tra- parts. ditional senses, we can clearly “feel” the passage of time as we Most historians credit the Egyptians with being the first civ- watch night turn to day, the seasons change, or a child grow up. ilization to use clocks. Their first clocks were probably nothing We are also aware that we can’t stop or reverse the continuous more than sticks placed in the ground that indicated time by flow of time, a fact that becomes more obvious as we get older. both the length and direction of their shadow. As early as 1500 Defining time seems impossible, and attempts to do so by phi- BC, the Egyptians had developed a more advanced shadow losophers and scientists fall far short of their goal. clock (Fig. 1). This T-shaped instrument was placed in a sun- In spite of its elusiveness, we can measure time exception- lit area on the ground. In the morning, the crosspiece (AA) was ally well. In fact, we can measure time with more resolution set to face east and then rotated in the afternoon to face west. -

From Sundials to Atomic Clocks

2 I. THE RIDDLE OF TIME 1. The Riddle of Time 3 The Nature of Time 4 What Is Time? 5 Date, Time Interval, and Synchronization 6 Ancient Clock Watchers 7 Clocks in Nature 9 Keeping Track of the Sun and Moon 10 Thinking Big and Thinking Small-An Aside on Numbers 12 2. Everything Swings 15 Getting Time from Frequency 17 What Is a Clock? 19 The Earth-Sun Clock 20 Meter Sticks to Measure Time 22 What Is a Standard? 23 How Time Tells Us Where in the World We Are 24 Building a Clock that Wouldn’t Get Seasick 26 3 P Chapter C m234567 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 It’s present everywhere, but occupies no space. We can measure it, but we can’t see it, touch it, get rid of it, or put it in a container. Everyone knows what it is and uses it every day, but no one has been able to define it. We can spend it, save it, waste it, or kill it, but we can’t destroy it or even change it, and there’s never any more or less of it. F “SE WE USE IT EVERY DAY! BUT WHAT 4 All of these statements apply to time. Is it any wonder that scientists like Newton, Descartes, and Einstein spent years studying, thinking about, arguing over, and trying to define time-and still were not satisfied with their answers? Today’s scientists have done no better. -

Giant Water Clock

CREATED IN 1925. MOVED TO CURRENT LOCATION IN 1946. Giant Water Clock Standing at 26.5 feet, The Children’s Gitton’s towering clocks are found in Museum Water Clock is the largest in major cities around the world, including: North America! Paris, Berlin, Tokyo, and Rio de Janeiro. Water clocks date back to ancient Egypt Peter Sterling, a former museum president, and ancient Greece, but none can match saw one of Bernard Gitton’s clocks in Brazil Gitton’s in accuracy or innovation. and was struck by its beauty and scientific genius. Sterling sought out the artist/inventor More than 40 glass pieces specially blown in his native France and was responsible in factories throughout Europe, 100 metal for bringing him to the United States. pieces, and 70 gallons of a water/methyl Gitton built and assembled the clock in alcohol mixture comprise the clock. The number of filled hour spheres lining the left side of the clock and the number of filled discs on the minutes side of the clock tell visitors the time of day. Each minutes disc represents two minutes. A pump hidden below the base of the clock pushes the liquid into a reservoir tank at the top of the clock. From there it flows into a glass cupel (a shallow cup or scoop) attached to a green neon pendulum. As the cupel fills, the increasing weight causes its arm to dip and empty the liquid. The cupel then returns to an upright position, thus propelling the pendulum. This occurs every two seconds, keeping a steady stream of liquid flowing into the clock’s systems of siphons. -

It's About Time Transcript

It’s about time Transcript Date: Thursday, 19 March 2009 - 1:00PM Location: Staple Inn Hall IT'S ABOUT TIME Professor Ian Morison "Time is nature's way of preventing everything happening at once." -John Wheeler Let us first discuss how astronomers measured the passage of time until the 1960's. Local Solar Time For centuries, the time of day was directly linked to the Sun's passage across the sky, with 24 hours being the time between one transit of the Sun across the meridian (the line across the sky from north to south) and that on the following day. This time standard is called 'Local Solar Time' and is the time indicated on a sundial. The time such clocks would show would thus vary across the United Kingdom, as Noon is later in the west. It is surprising the difference this makes. In total, the United Kingdom stretches 9.55 degrees in longitude from Lowestoft in the east to Mangor Beg in County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland in the west. As 15 degrees is equivalent to 1 hour, this is a time difference of just over 38 minutes! Greenwich Mean Time As the railways progressed across the UK, this difference became an embarrassment and so London or 'Greenwich' time was applied across the whole of the UK. A further problem had become apparent as clocks became more accurate: due to the fact that, as the Earth's orbit is elliptical, the length of the day varies slightly. Thus 24 hours, as measured by clocks, was defined to be the average length of the day over one year. -

MD–90 Series Precision Quartz Clock Manufactured by Mid-Continent Instruments and Avionics

MD–90 Series Precision Quartz Clock Manufactured by Mid-Continent Instruments and Avionics PRECISION QUARTZ CLOCK PRECISION QUARTZ THE MD – 90 SERIES IS DESIGNED FOR ACCURACY AND IS TRUSTED BY MANY AIRCRAFT MANUFACTURERS MD–90 AND OWNERS. Accurate time-keeping is important to an instrument pilot, Precision quartz movement and it is a requirement that a timepiece with a sweep second Compact 2-inch size — fits standard panel cutout pointer be on board the airplane. The MD–90 Series Precision Lighted version available with field-replaceable light tray Quartz Clock is the ideal solution. Transient and reverse polarity protected The 2-inch MD–90 Series features extremely low current Original equipment for many major aircraft manufacturers draw, transient and reverse polarity protection. Each clock is Low power consumption (3 mA) manufactured to meet rugged aircraft environmental standards. Continuously powered by aircraft battery With a high-quality, solid-state quartz movement and a variety of lighting options, a 12-hour analog clock is an essential FAA PMA certified part of any instrument panel. Designed and built in Wichita, Kansas, USA One-year limited warranty Kansas 9400 East 34th Street North Wichita, Kansas 67226 USA Tel 316.630.0101 Tel 800.821.1212 Fax 316.630.0723 E-mail [email protected] California 16320 Stagg Street Van Nuys, California 91406 USA Tel 818.786.0300 Tel 800.345.7599 Fax 818.786.2734 E-mail [email protected] mcico.com MD–90 Series Precision Quartz Clocks Manufactured by Mid-Continent Instruments and Avionics SPECIFICATIONS Power Input 8–32 VDC 3 mA max (without lighting) Accuracy ±30 seconds in 24 hrs Dimensions 2.5 x 2.5 x 3.2 inches max Weight 0.5 lbs Temperature –40°C to +82°C (–40°F to +180°F) Altitude –1,000 to +55,000 ft Humidity 0 to 95% at 25°C Vibration 02 in. -

Time Keeping Experiments for a Mechanical Engineering Education Laboratory Sequence

AC 2009-439: TIME-KEEPING EXPERIMENTS FOR A MECHANICAL ENGINEERING EDUCATION LABORATORY SEQUENCE John Wagner, Clemson University Katie Knaub, National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors Page 14.1271.1 Page © American Society for Engineering Education, 2009 Time Keeping Experiments for a Mechanical Engineering Education Laboratory Sequence Abstract The evolution of science and technology throughout history parallels the development of time keeping devices which assist mankind in measuring and coordinating their daily schedules. The earliest clocks used the natural behavior of the sun, sand, and water to approximate fixed time intervals. In the medieval period, mechanical clocks were introduced that were driven by weights and springs which offered greater time accuracy due to improved design and materials. In the last century, electric motor driven clocks and digital circuits have allowed for widespread distribution of clock devices to many homes and individuals. In this paper, a series of eight laboratory experiments have been created which use a time keeping theme to introduce basic mechanical and electrical engineering concepts, while offering the opportunity to weave societal implications into the discussions. These bench top and numerical studies include clock movements, pendulums, vibration and acoustic analysis, material properties, circuit breadboards, microprocessor programming, computer simulation, and artistic water clocks. For each experiment, the learning objectives, equipment and materials, and laboratory procedures are listed. To determine the learning effectiveness of each experiment, an assessment tool will be used to gather student feedback for laboratory improvement. Finally, these experiments can also be integrated into academic programs that emphasize science, technology, engineering and mathematical concepts within a societal context.