Madison Symphony Orchestra Program Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Generazione Dell'ottanta and the Italian Sound

LA GENERAZIONE DELL’OTTANTA AND THE ITALIAN SOUND A DISSERTATION IN Trumpet Performance Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS by ALBERTO RACANATI M.M., Western Illinois University, 2016 B.A., Conservatorio Piccinni, 2010 Kansas City, Missouri 2021 LA GENERAZIONE DELL’OTTANTA AND THE ITALIAN SOUND Alberto Racanati, Candidate for the Doctor of Musical Arts Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2021 ABSTRACT . La Generazione dell’Ottanta (The Generation of the Eighties) is a generation of Italian composers born in the 1880s, all of whom reached their artistic maturity between the two World Wars and who made it a point to part ways musically from the preceding generations that were rooted in operatic music, especially in the Verismo tradition. The names commonly associated with the Generazione are Alfredo Casella (1883-1947), Gian Francesco Malipiero (1882-1973), Ildebrando Pizzetti (1880-1968), and Ottorino Respighi (1879- 1936). In their efforts to create a new music that sounded unmistakingly Italian and fueled by the musical nationalism rampant throughout Europe at the time, the four composers took inspiration from the pre-Romantic music of their country. Individually and collectively, they embarked on a journey to bring back what they considered the golden age of Italian music, with each one yielding a different result. iii Through the creation of artistic associations facilitated by the fascist government, the musicians from the Generazione established themselves on the international scene and were involved with performances of their works around the world. -

La Nuova Musica (1896-1919)

La Nuova Musica (1896-1919) The music periodical La Nuova musica [NMU] was first published on 31 January 1896 by its founder, the pianist and composer Edgardo Del Valle de Paz (1861- 1920), a professor of piano at the Istituto Musicale in Florence, who directed and administered the journal without interruption until its final issue. NMU was published monthly from 1896 to 1907, fortnightly from 1908 to 1910, bimonthly during 1911 and fortnightly from 1912 to its cessation. Throughout the publication pages measuring 34 x 25 cm. are printed in three column format and are numbered beginning with number 1 for successive years. La Nuova musica documents Florentine music history and bridges a gap existing in Italian music periodical literature since 1882, when the earlier Florentine periodical Boccherini (1862-1882) ceased publication. The aim of the periodical is to diffuse by print the most notable music, to raise the musical level of the public by making it aware of the most excellent works of our masters, to give our young composers an opportunity to publicize in print their first compositions, [and] to express openly their opinions. Each issue of NMU contains two sections: testo, features articles about music events and music criticism, and constitutes the main six or eight page section of the periodical; and, musica, a supplement of eight pages consisting of two or three compositions for piano or for voice and piano. This two-fold structure is suspended beginning with the first issue of 1909. The first pages of each issue are generally reserved for a critical essay concerning contemporary topics, followed by an article of historical interest. -

550533-34 Bk Mahler EU

CASELLA Divertimento for Fulvia Donatoni Music for Chamber Orchestra Ghedini Concerto grosso Malipiero Imaginary Orient Orchestra della Svizzera italiana Damian Iorio Alfredo Casella (1883-1947): Alfredo Casella (1883-1947) • Franco Donatoni (1927-2000) Divertimento per Fulvia (Divertimento for Fulvia), Op. 64 (1940) 15:21 Giorgio Federico Ghedini (1892-1965) • Gian Francesco Malipiero (1882-1973) 1 I. Sinfonia (Overture). Allegro vivace e spiritoso, alla marcia 2:05 2 II. Allegretto. Allegretto moderato ed innocente 1:42 ‘A crucial figure: few modern musicians in any country can advised Casella’s parents that to find tuition that would do 3 II. Valzer diatonico (Diatonic Waltz). Vivacissimo 1:43 compare with him for sheer energy, enlightenment and justice to his talent, they would need to send him abroad. persistence in his many-sided activities as leader, 1896 was a watershed in Casella’s life: his father died, 4 VI. Siciliana. Molto dolce e espressivo, come una melodia popolare (Very sweet and expressive, like a folk melody) 2:25 organiser, conductor, pianist, teacher and propagandist – after a long illness; and he moved to Paris with his mother one marvels that he had any time left for composing.’ The to study at the Conservatoire. Casella was to remain in 5 V. Giga (Jig). Tempo di giga inglese (English jig time) (Allegro vivo) 1:54 musician thus acclaimed by the English expert on Italian Paris for almost twenty years, cutting his teeth in the most 6 VI. Carillon. Allegramente 1:05 music John C.G. Waterhouse was Alfredo Casella – who dynamic artistic milieu of the time as pianist, composer, 7 VII. -

Giuseppe Martucci (Geb. Capua, 6. Januar 1856 — Gest. Neapel, 1

Giuseppe Martucci (geb. Capua, 6. Januar 1856 — gest. Neapel, 1. Juni 1909) La Canzone dei Ricordi (1886-87/orch. 1899) Poemetto lirico di Rocco E. Pagliara I Svaniti, non sono i sogni. Andantino p. 1 II Cantava’l ruscello la gaia canzone. Allegretto con moto p. 10 III Fior di ginestra. Andantino – Allegretto giusto – Tempo I p. 35 IV Sul mar la navicella. Allegretto con moto p. 53 V Un vago mormorio mi giunge. Andante p. 66 VI Al folto bosco, placida ombria. Andantino con moto – Allegro agitato – Tempo I p. 83 VII No, svaniti non sono i sogni. Andantino p. 117 Vorwort Als der Pionier der Wiederbelebung der italienischen Instrumentalmusik in einer Zeit, die fast ausschließlich auf die Oper konzentriert war, ist der Römer Giovanni Sgambati (1841-1914) anzusehen, Günstling Liszts und Wagners, exzellenter Pianist, Dirigent und Komponist. Ihm folgte Giuseppe Martucci, Sohn eines Trompeters und Kapellmeisters und ebenfalls als Pianist (von Liszt und Anton Rubinstein bewundert), Dirigent und Komponist eine herausragende, noch weit markantere und schöpferisch fruchtbarere Persönlichkeit. Der Dirigent Martucci setzte in Italien nicht nur Richard Wagners Musik durch (italienische Erstaufführung von Tristan und Isolde am 2. Juni 1888 im Teatro Comunale zu Bologna), sondern setzte sich auch nachdrücklich für Johannes Brahms, Carl Goldmark (1830-1915), Richard Strauss, Edouard Lalo (1823-92), Claude Debussy, Arthur Sullivan (1842-1900), Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924) u. a. ein. Siebenjährig trat Martucci erstmals öffentlich als Pianist auf, mit elf Jahren begann er sein Studium am Conservatorio di San Pietro a Majella zu Neapel, wo der Mercadante-Schüler Paolo Serrao (1830-1907) sein Kompositionslehrer war. -

The Reception of Bach in Fin-De-Siecle Italy: Giuseppe Martucci’S Transcriptions of the Orchestral Suites

THE RECEPTION OF BACH IN FIN-DE-SIECLE ITALY: GIUSEPPE MARTUCCI’S TRANSCRIPTIONS OF THE ORCHESTRAL SUITES Chiara Bertoglio Even in nineteenth-century Italy, whose main musical interest was doubtlessly opera and which could fear (including for nationalistic reasons) the cultural colonization of German instrumental music, there were cities where Bach’s music was appreciated and sometimes performed, particularly where the Bach cult was promoted by enthusiastic individuals. In Bologna, for example, the significant influence of the erudite scholar Padre Martini was sustained by his disciples; the library of the Liceo Filarmonico, a conservatory-like institution founded in 1804, became the recipient of Martini’s extraordinary collection, partly directly after Martini’s death and partly after it passed through the hands of his favorite student, Stanislao Mattei. Another librarian in charge of this collection, Gaetano Gaspari, was one of the first organ performers to regularly play Bach’s works in Bologna and the surrounding regions. Another Bach city was certainly Naples, where Francesco Lanza (1783-1862)—a former student of John Field—taught piano at the Real Collegio di Musica. Also crucial for the appreciation of Bach was the presence in Posillipo of Sigismund Thalberg, who taught, among others, Beniamino Cesi. In 1855, Thalberg had emphatically advised the students of the Real Collegio to systematically study Bach’s fugues, giving a good example by opening his recital with one of them (Ferraris 2010: 9). It is not by chance, therefore, that the life of Giuseppe Martucci substantially revolved around the two poles of Naples and Bologna. Born near Naples in 1856, he was a child prodigy with little formal education, until this same Beniamino Cesi convinced Martucci’s father to send him to the local conservatory, where Cesi himself became his piano teacher. -

Martucci US 4/2/09 11:19 AM Page 5

8.570932 bk Martucci US 4/2/09 11:19 AM Page 5 Gesualdo Coggi Born in 1985, Gesualdo Coggi was awarded his diploma in 2002 with the maximum votes and Giuseppe distinction under Maestro F. Di Cesare at the Santa Cecilia Conservatory in Rome, receiving in 2003 the Valter Cococcia Prize for the youngest Italian graduate of the preceding year. He Francesco La Vecchia completed further study at the Rotterdam Conservatory and is now under the guidance of MARTUCCI Maestro R. Cappello at the Boito Conservatory in Parma. He has participated in a number of distinguished master-classes with leading pianists and appeared in concerts in Salzburg, Seoul, Geneva, Rotterdam, Ravenna, Venice, Parma, Stresa, Rome and elsewhere. In July 2007 he Piano Concerto No. 2 was awarded the Laurea Triennale in Physics at La Sapienza University in Rome. Momento Musicale e Minuetto • Novelletta Serenata • Colore orientale Orchestra Sinfonica di Roma Gesualdo Coggi, Piano The Rome Symphony Orchestra was established in 2002 by the Rome Foundation and is a rare example in Europe of an orchestra that is completely privately funded. The orchestra has won wide international critical recognition, Orchestra Sinfonica di Roma including performances in the presence of four heads of state, the Queen of Spain and the Queen of the Netherlands. Orchestra Sinfonica di Roma The Artistic and Musical Director is Francesco La Vecchia. Leading choruses, soloists and conductors, have Francesco La Vecchia collaborated with the orchestra and concert tours have taken it to major international venues in Asia, the Americas and Europe, with notable success in 2007 at the Berlin Philharmonic. -

Ottorino Respighi Concerto All’Antica Ancient Airs and Dances Suites Nos

OTTORINO RESPIGHI CONCERTO ALL’ANTICA ANCIENT AIRS AND DANCES SUITES NOS. 1–3 DAVIDE ALOGNA VIOLIN CHAMBER ORCHESTRA OF NEW YORK SALVATORE DI VITTORIO Ottorino RESPIGHI (1879–1936) Ottorino Concerto all’antica • Ancient Airs and Dances, Suites Nos. 1–3 The renowned Italian composer Ottorino Respighi as well as composition with Giuseppe Martucci RESPIGHI (Bologna, 9 July 1879 – Rome, 18 April 1936) is and musicology with Luigi Torchi – a scholar of (1879–1936) perhaps most well known for his Roman Trilogy: Early Music. Following his graduation from the Concerto all’antica, P. 75 (1908) * ......................................................................... 30:13 Fountains of Rome, Pines of Rome and Roman conservatory in 1900, Respighi travelled to Russia 1 I. Allegro ..................................................................................................................................12:47 Festivals. His compositions from the 20th century to become principal violist for the Russian Imperial 2 II. Adagio non troppo ................................................................................................................8:15 signalled the rebirth of Italian symphonic music, and Theatre Orchestra of St Petersburg for its season 3 III. Vivace – Tempo di minuetto – Tempo I ...............................................................................9:11 a restored appreciation of Renaissance and Baroque of Italian opera. During his stay, Respighi studied musical forms. His orchestral works are thus composition for five months with Rimsky-Korsakov. considered the culmination of the Italian symphonic He then returned to Bologna to earn a second Antiche danze ed arie per liuto (‘Ancient Airs and Dances’) repertoire. Of equal importance, Respighi embraced degree in composition. From 1908 to 1909 he spent Suite No. 1, P. 109 (1917) ............................................................................................ 14:46 the continuity of tradition with a love of the ancient some time performing in Germany and also studied 4 I. -

8.570931 Bk Martucci US 19/3/09 15:19 Page 8

8.570931 bk Martucci US 19/3/09 15:19 Page 8 Giuseppe Francesco La Vecchia MARTUCCI Piano Concerto No. 1 La canzone dei ricordi Gesualdo Coggi, Piano • Silvia Pasini, Mezzo-soprano Orchestra Sinfonica di Roma Francesco La Vecchia Orchestra Sinfonica di Roma Photos: Antonio Tirocchi 8.570931 8 8.570931 bk Martucci US 19/3/09 15:19 Page 2 Giuseppe Martucci (1856-1909): Complete Orchestral Music • 3 8 Un vago mormorío mi giunge: muta, 0 No... svaniti non sono i sogni, e cedo, rimango ad origliare, e’l cor tremante e m’abbandono alle tristezze loro: Piano Concerto No. 1 in D minor, Op. 40 • La canzone dei ricordi una dolce speranza risaluta. chiudo gli occhi pensosi e ti rivedo Giuseppe Martucci was born in Capua on 6th January his interest in French music saw him advocate Franck, Ahi, mi par di vederlo a me d’innate! come in un nimbo di faville d’oro! 1856 and had initial piano lessons from his father. He d’Indy and latterly Debussy. Ma’l mormorío che m’ha portato’l vento Ma... tu passi nell’aere, gave recitals with his sister before he was nine and was a Although the piano dominates Martucci’s output è sussurro di rami e non d’amor! dileguante... per lontano orizzonte... full-time student at the Real Collegio in Naples from (notably his earlier years), he wrote several major L’inganno è già svanito d’un momento: indefinito!... 1868, studying the piano with Beniamino Cesi and chamber works, including a Piano Quintet, two Piano torno a piangere ancor! composition with Paolo Serrao, whose advocacy of the Trios and sonatas for violin and cello, with orchestral Lambisce’l capo mio gentil carezza, Austro-German repertoire, unusual in Italy for that time, music represented by various transcriptions as well as e mi riscote e turba i sensi miei: had a decisive influence on Martucci. -

Oct 26 to Nov 1.Txt

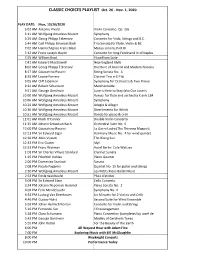

CLASSIC CHOICES PLAYLIST Oct. 26 - Nov. 1, 2020 PLAY DATE: Mon, 10/26/2020 6:02 AM Antonio Vivaldi Violin Concerto, Op. 3/6 6:11 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony 6:29 AM Georg Philipp Telemann Concerto for Viola, Strings and B.C. 6:44 AM Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach Trio Sonata for Flute, Violin & BC 7:02 AM Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber Mensa sonora, Part III 7:12 AM Franz Joseph Haydn Concerto for King Ferdinand IV of Naples 7:29 AM William Byrd Fitzwilliam Suite 7:41 AM Edward MacDowell New England Idylls 8:02 AM Georg Philipp Telemann Overture of Ancient and Modern Nations 8:17 AM Gioacchino Rossini String Sonata No. 5 8:33 AM Louise Farrenc Clarinet Trio in E-Flat 9:05 AM Cliff Eidelman Symphony for Orchestra & Two PIanos 9:34 AM Robert Schumann Märchenbilder 9:51 AM George Gershwin Love is Here to Stay (aka Our Love is 10:00 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Rondo for flute and orchestra K anh.184 10:06 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony 10:24 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Adagio & Allegro 10:36 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Divertimento for Winds 10:51 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Rondo for piano & orch 11:01 AM Mark O'Connor Double Violin Concerto 11:35 AM Johann Sebastian Bach Orchestral Suite No. 4 12:00 PM Gioacchino Rossini La Gazza Ladra (The Thieving Magpie): 12:13 PM Sir Edward Elgar Harmony Music No. 4 for wind quintet 12:26 PM Allen Vizzutti The Rising Sun 12:43 PM Eric Coates Idyll 12:51 PM Franz Waxman Hotel Berlin: Cafe Waltzes 1:01 PM Sir Charles Villiers Stanford Clarinet Sonata 1:25 PM Friedrich Kuhlau Piano Quartet 2:00 PM Domenico Scarlatti Sonata 2:08 PM Nicolo Paganini Quartet No. -

Jeremy Dibble

Jeremy Dibble Michele Esposito Jeremy Dibble skilfully reconstructs the life and career of Michele Esposito (1855–1929) – a figure of seminal importance in the history of Irish music of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Neapolitan by birth and education, Esposito moved to Dublin in 1882 and became an artistic leader in the organization of the chamber concerts for the Royal Dublin Society and the foundation of the Dublin Orchestral Society, the city’s first professional orchestra. He was also involved with the Literary Revival and the Feis Ceoil during the turbulent half-century he spent in Dublin. This important book introduces us to the life and work of a dedicated composer, teacher and organizer whose influence needs to be recognized and appreciated both by all who are interested either in music or in Irish cultural history. Jeremy Dibble is Professor of Music at the University of Durham. He is a noted authority on British and Irish music of the 19th and 20th centuries. His previous publications include monographs on Hubert Parry, Charles Villiers Stanford and John Stainer. Michele Esposito Michele Esposito Jeremy Dibble Field Day Music 3 Series Editors: Séamas de Barra and Patrick Zuk Field Day Publications Dublin, 2010 Jeremy Dibble has asserted his right under the Copyright and Related Rights Act, 2000, to be identified as the author of this work. Copyright © by Jeremy Dibble 2010 ISBN 978-0-946755-47-9 Published by Field Day Publications in association with the Keough-Naughton Institute for Irish Studies at the University of Notre Dame. Field Day Publications Newman House 86 St. -

Proquest Dissertations

Piano music in Italy at the turn of the twentieth century: Alfredo Casella and Gian Francesco Malipiero Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Perry, Margaret C. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 29/09/2021 02:41:20 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/280046 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author dkJ not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indrcate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing f^ left to right in equal sectkins with small overiaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6' x 9* black and white photographk: prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an addittonal charge. -

Vol. 15, No.4 March 2008

Cockaigne (In London Town) • Concert Allegro • Grania and Diarmid • May Song • Dream Children • Coronation Ode • Weary Wind of the West • Skizze • Offertoire • The Apostles • In The South (Alas- sio) • Introduction and Allegro • Evening Scene • In Smyrna • The Kingdom • Wand of Youth • HowElgar Calmly Society the Evening • Pleading • Go, Song of Mine • Elegy • Violin Concerto in B minor • Romance • Symphony No.2 •ournal O Hearken Thou • Coronation March • Crown of India • Great is the Lord • Cantique • The Music Makers • Falstaff • Carissima • Sospiri • The Birthright • The Windlass • Death on the Hills • Give Unto the Lord • Carillon • Polonia • Une Voix dans le Desert • The Starlight Express • Le Drapeau Belge • The Spirit of England • The Fringes of the Fleet • The Sanguine Fan • Violin Sonata in E minor • String Quartet in E minor • Piano Quintet in A minor • Cello Concerto in E minor • King Arthur • The Wanderer • Empire March • The Herald • Beau Brummel • Severn Suite • Solilo- quy • Nursery Suite • Adieu • Organ Sonata • Mina • The Spanish Lady • Chantant • Reminiscences • Harmony Music • Promenades • Evesham Andante • Rosemary (That's for Remembrance) • Pas- tourelle • Virelai • Sevillana • Une Idylle • Griffinesque • Gavotte • Salut d'Amour • Mot d'Amour • Bizarrerie • O Happy Eyes • My Love Dwelt in a Northern Land • Froissart • Spanish Serenade • La Capricieuse • Serenade • The Black Knight • Sursum Corda • The Snow • Fly, Singing Bird • From the Bavarian Highlands • The Light of Life • King Olaf • ImperialMARCH March 2008 Vol. • The15, No. Banner 4 of St George • Te Deum and Benedictus • Caractacus • Variations on an Original Theme (Enigma) • Sea Pictures • Chanson de Nuit • Chanson de Ma- tin • Three Characteristic Pieces • The Dream of Gerontius • Ser- enade Lyrique • Pomp and Circumstance • The Elgar Society The Elgar Society Journal Founded 1951 362 Leymoor Road, Golcar, Huddersfield, HD7 4QF Telephone: 01484 649108 Email: [email protected] President Richard Hickox, CBE March 2008 Vol.