'Not Enough Benches in the Pjazza': Forced Migrants, Integration, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

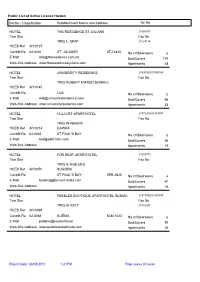

Public List of Active Licence Holders Tel No Sector / Classification

Public List of Active Licence Holders Sector / Classification Establishment Name and Address Tel No HOTEL THE RESIDENCE ST JULIANS 21360031 Two Star Fax No TRIQ L. APAP 21374114 HCEB Ref AH/0137 Contrib Ref 02-0044 ST. JULIAN'S STJ 3325 No Of Bedrooms 0 E Mail [email protected] Bed/Covers 124 Web-Site Address www.theresidencestjulians.com Apartments 48 HOTEL UNIVERSITY RESIDENCE 21430360/21436168 Two Star Fax No TRIQ ROBERT MIFSUD BONNICI HCEB Ref AH/0145 Contrib Ref LIJA No Of Bedrooms 0 E Mail [email protected] Bed/Covers 66 Web-Site Address www.universityresidence.com Apartments 33 HOTEL HULI CRT APARTHOTEL 21572200/21583741 Two Star Fax No TRIQ IN-NAKKRI HCEB Ref AH/0214 QAWRA Contrib Ref 02-0069 ST.PAUL'S BAY No Of Bedrooms 0 E Mail [email protected] Bed/Covers 56 Web-Site Address Apartments 19 HOTEL FOR REST APARTHOTEL 21575773 Two Star Fax No TRIQ IL-HGEJJEG HCEB Ref AH/0370 BUGIBBA Contrib Ref ST.PAUL'S BAY SPB 2825 No Of Bedrooms 4 E Mail [email protected] Bed/Covers 40 Web-Site Address Apartments 16 HOTEL PEBBLES BOUTIQUE APARTHOTEL SLIEMA 21311889/21335975 Two Star Fax No TRIQ IX-XATT 21316907 HCEB Ref AH/0395 Contrib Ref 02-0068 SLIEMA SLM 1022 No Of Bedrooms 0 E Mail [email protected] Bed/Covers 92 Web-Site Address www.pebbleshotelmalta.com Apartments 26 Report Date: 30/08/2019 1-21PM Page xxxxx of xxxxx Public List of Active Licence Holders Sector / Classification Establishment Name and Address Tel No HOTEL ALBORADA APARTHOTEL (BED & BREAKFAST) 21334619/21334563 Two Star 28 Fax No TRIQ IL-KBIRA -

Indiċi Tal-Gazzetta Tal-Gvern Ta' Malta 2007 ___

INDIĊI TAL-GAZZETTA TAL-GVERN TA’ MALTA 2007 _________ A A Nru. ta’ Nru. ta’ Avviż Paġna Avviż Paġna ABBOZZI TA’ LIĠIJIET - PUBBLIKAZZJONI TA’: Abbozz ta’ Liġi Nru. 106 imsejjaħ Att ta’ l-2008 li jimplimenta Miżuri ta’ l-Estimi 915 9247 Abbozz ta’ Liġi Nru. 87 imsejjaħ l-Att ta’ l-2007 Abbozz ta’ Liġi Nru. 107 imsejjaħ Att ta’ l-2007 li jemenda diversi liġijiet 15 113 li jemenda l-Att dwar l-Awtorità tad-Djar 929 9303 Abbozz ta’ Liġi Nru. 88 imsejjaħ Att ta’ l-2007 Abbozz ta’ Liġi Nru. 110 imsejjaħ Att ta’ l-2007 li jemenda l-Att dwar il-Kumpanniji 269 3264 li jemenda Diversi Liġijiet li Jirrigwardaw Abbozz ta’ Liġi Nru. 89 imsejjaħ Att ta’ l-2007 Materji Kriminali 992 10131 dwar il-Foster Care 318 3807 Abbozz ta’ Liġi Nru. 111 imsejjaħ Att ta’ l-2007 Abbozz ta’ Liġi Nru. 90 imsejjaħ Att ta’ l-2007 dwar l-Amministrazzjoni ta’ l-Adozzjoni u li jemenda l-Ordinanza li Tneħħi l-Kontroll Abbozz ta’ Liġi Nru. 112 imsejjaħ Att ta’ l-2007 tad-Djar 356 4039 li jemenda l-Att dwar l-Affarijiet tal-Konsumatur 995 10135 Abbozz ta’ Liġi Nru. 91 imsejjaħ Att ta’ l-2007 Abbozz ta’ Liġi Nru. 113 imsejjaħ Att ta’ l-2007 li jemenda l-Att dwar it-Taxxa fuq l-Income u biex jemenda l-Att dwar Awtorità dwar Abbozz ta’ Liġi Nru. 92 imsejjaħ Att ta’ l-2007 it-Trasport ta’ Malta 1042 10447 li jemenda l-Kodiċi Kriminali 359 4047 Abbozz ta’ Liġi Nru. -

Gazzetta Tal-Gvern Ta' Malta

Nru./No. 20,582 Prezz/Price €2.70 Gazzetta tal-Gvern ta’ Malta The Malta Government Gazette L-Erbgħa, 3 ta’ Marzu, 2021 Pubblikata b’Awtorità Wednesday, 3rd March, 2021 Published by Authority SOMMARJU — SUMMARY Avviżi tal-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar ....................................................................................... 1869 - 1924 Planning Authority Notices .............................................................................................. 1869 - 1924 It-3 ta’ Marzu, 2021 1869 PROĊESS SĦIĦ FULL PROCESS Applikazzjonijiet għal Żvilupp Sħiħ Full Development Applications Din hija lista sħiħa ta’ applikazzjonijiet li waslu għand This is a list of complete applications received by the l-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar. L-applikazzjonijiet huma mqassmin Planning Authority. The applications are set out by locality. bil-lokalità. Rappreżentazzjonijiet fuq dawn l-applikazzjonijiet Any representations on these applications should be sent in għandhom isiru bil-miktub u jintbagħtu fl-uffiċini tal-Awtorità writing and received at the Planning Authority offices or tal-Ippjanar jew fl-indirizz elettroniku ([email protected]. through e-mail address ([email protected]) within mt) fil-perjodu ta’ żmien speċifikat hawn taħt, u għandu the period specified below, quoting the reference number. jiġi kkwotat in-numru ta’ referenza. Rappreżentazzjonijiet Representations may also be submitted anonymously. jistgħu jkunu sottomessi anonimament. Is-sottomissjonijiet kollha lill-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar, All submissions to the Planning Authority, -

How to Submit the Retirement Pension Scheme Report Contents

CfR SERVICES ONLINE Submission of Retirement Pensions Scheme Report (Global Return) How to Submit the Retirement Pension Scheme Report Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 3 Data Required ....................................................................................................................... 4 Country Codes ...................................................................................................................... 5 Additional Information .......................................................................................................... 7 Submission of the report........................................................................................................ 7 Online Filing ......................................................................................................................... 8 Step 1 – Register within the CfR’s online services ............................................................. 8 Step 2 – Register for an e-ID ............................................................................................. 8 Step 3 – 2-Factor authentication ........................................................................................ 8 Step 4 – Submitting your data ............................................ Error! Bookmark not defined. File Maintenance ............................................................................................................. 11 For further -

Malta & Gozo Directions

DIRECTIONS Malta & Gozo Up-to-date DIRECTIONS Inspired IDEAS User-friendly MAPS A ROUGH GUIDES SERIES Malta & Gozo DIRECTIONS WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY Victor Paul Borg NEW YORK • LONDON • DELHI www.roughguides.com 2 Tips for reading this e-book Your e-book Reader has many options for viewing and navigating through an e-book. Explore the dropdown menus and toolbar at the top and the status bar at the bottom of the display window to familiarize yourself with these. The following guidelines are provided to assist users who are not familiar with PDF files. For a complete user guide, see the Help menu of your Reader. • You can read the pages in this e-book one at a time, or as two pages facing each other, as in a regular book. To select how you’d like to view the pages, click on the View menu on the top panel and choose the Single Page, Continuous, Facing or Continuous – Facing option. • You can scroll through the pages or use the arrows at the top or bottom of the display window to turn pages. You can also type a page number into the status bar at the bottom and be taken directly there. Or else use the arrows or the PageUp and PageDown keys on your keyboard. • You can view thumbnail images of all the pages by clicking on the Thumbnail tab on the left. Clicking on the thumbnail of a particular page will take you there. • You can use the Zoom In and Zoom Out tools (magnifying glass) to magnify or reduce the print size: click on the tool, then enclose what you want to magnify or reduce in a rectangle. -

L-20 Ta' Jannar, 2021

L-20 ta’ Jannar, 2021 433 PROĊESS SĦIĦ FULL PROCESS Applikazzjonijiet għal Żvilupp Sħiħ Full Development Applications Din hija lista sħiħa ta’ applikazzjonijiet li waslu għand This is a list of complete applications received by the l-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar. L-applikazzjonijiet huma mqassmin Planning Authority. The applications are set out by locality. bil-lokalità. Rappreżentazzjonijiet fuq dawn l-applikazzjonijiet Any representations on these applications should be sent in għandhom isiru bil-miktub u jintbagħtu fl-uffiċini tal-Awtorità writing and received at the Planning Authority offices or tal-Ippjanar jew fl-indirizz elettroniku ([email protected]. through e-mail address ([email protected]) within mt) fil-perjodu ta’ żmien speċifikat hawn taħt, u għandu the period specified below, quoting the reference number. jiġi kkwotat in-numru ta’ referenza. Rappreżentazzjonijiet Representations may also be submitted anonymously. jistgħu jkunu sottomessi anonimament. Is-sottomissjonijiet kollha lill-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar, All submissions to the Planning Authority, submitted sottomessi fiż-żmien speċifikat, jiġu kkunsidrati u magħmula within the specified period, will be taken into consideration pubbliċi. and will be made public. L-avviżi li ġejjin qed jiġu ppubblikati skont Regolamenti The following notices are being published in accordance 6(1), 11(1), 11(2)(a) u 11(3) tar-Regolamenti dwar l-Ippjanar with Regulations 6(1), 11(1), 11(2)(a), and 11(3) of the tal-Iżvilupp, 2016 (Proċedura ta’ Applikazzjonijiet u Development Planning (Procedure for Applications and d-Deċiżjoni Relattiva) (A.L.162 tal-2016). their Determination) Regulations, 2016 (L.N.162 of 2016). Rappreżentazzjonijiet fuq l-applikazzjonijiet li ġejjin Any representations on the following applications should għandhom isiru sad-19 ta’ Frar, 2021. -

Tallinja Card Registration Form

Malta Public Transport Mdina Road, Qormi QRM 9010, Malta publictransport.com.mt Tallinja Card Registration Form The Tallinja Card is a personalised transport card used on the public transport network in Malta and Gozo. Your photo and name will be printed on your card (except in the case of Child cards). The Tallinja Card may be topped up with credit online, using the Tallinja App, over the phone, at any of the sales outlets of Malta Public Transport or at any MaltaPost office. The form must be dropped off at any ticket booth together with all the required documents. 1. Name* 2. Surname* 3. Maltese Identity Card / Residence card / Passport / Other ID Document Number* AFFIX PHOTO HERE 4. Email address 5. Date of birth* dd / mm / yyyy 00 / 00 / 0000 6. Mobile number* 7. Landline 8. Photo (Not applicable to children between 4 & 10 years, both included) 9. Address: House Name* Street* Town* Postcode* Country* 10. Are you a holder of a Maltese EU Disability card issued by the Commission for the Rights of Persons with YES NO Disability (CRPD)?* ** If yes, please provide your Maltese EU Disability Card number: I give my consent to Malta Public Transport to access, process and share my personal information from YES NO CRPD to verify and confirm that I am a holder of a Maltese EU Disability card. This is required and necessary for the issuing of my Concession Tallinja Card, and for renewing it on a yearly basis. ** 11. Are you a student attending a full-time course with a recognised educational institution in Malta for a YES NO minimum of 3 months?* ** If yes, please provide the name of the educational institution: Please attach proof of attendance if aged 17 and above and applying for a Student Card. -

L-4 Ta' Diċembru, 2019

L-4 ta’ Diċembru, 2019 25,349 PROĊESS SĦIĦ FULL PROCESS Applikazzjonijiet għal Żvilupp Sħiħ Full Development Applications Din hija lista sħiħa ta’ applikazzjonijiet li waslu għand This is a list of complete applications received by the l-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar. L-applikazzjonijiet huma mqassmin Planning Authority. The applications are set out by locality. bil-lokalità. Rappreżentazzjonijiet fuq dawn l-applikazzjonijiet Any representations on these applications should be sent in għandhom isiru bil-miktub u jintbagħtu fl-uffiċini tal-Awtorità writing and received at the Planning Authority offices or tal-Ippjanar jew fl-indirizz elettroniku ([email protected]. through e-mail address ([email protected]) within mt) fil-perjodu ta’ żmien speċifikat hawn taħt, u għandu the period specified below, quoting the reference number. jiġi kkwotat in-numru ta’ referenza. Rappreżentazzjonijiet Representations may also be submitted anonymously. jistgħu jkunu sottomessi anonimament. Is-sottomissjonijiet kollha lill-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar, All submissions to the Planning Authority, submitted sottomessi fiż-żmien speċifikat, jiġu kkunsidrati u magħmula within the specified period, will be taken into consideration pubbliċi. and will be made public. L-avviżi li ġejjin qed jiġu ppubblikati skont Regolamenti The following notices are being published in accordance 6(1), 11(1), 11(2)(a) u 11(3) tar-Regolamenti dwar l-Ippjanar with Regulations 6(1), 11(1), 11(2)(a), and 11(3) of the tal-Iżvilupp, 2016 (Proċedura ta’ Applikazzjonijiet u Development Planning (Procedure for Applications and d-Deċiżjoni Relattiva) (A.L.162 tal-2016). their Determination) Regulations, 2016 (L.N.162 of 2016). Rappreżentazzjonijiet fuq l-applikazzjonijiet li ġejjin Any representations on the following applications should għandhom isiru sat-13 ta’ Jannar, 2020. -

II-Pjazza Ta' Tfulitna

II-Pjazza ta' Tfulitna Anton Mallia Borg Meta konna nsemmu l-pjazza konna minnufih nifhmu I-Pjazza Sant'Elena il- fetha kbira qud a diem it-tempju Elenjan, kapolavur tal-istil Barokk, Ii fl-1950, il-Papa Piju XII ghollih ghad-din jita' ta' Bazilka Minuri. Wara dan it-tempju kien hemm dik hekk imsejha barriera fejn fil-ftit kmajjar kienet tghix il-Familja Calleja Ii emigrat lejn I-Awstralja. Kien hemm zmien meta din il barriera xi hadd unilateralment ghaddiha lill-Klabb tal-bocci fejn diversi voluntiera attrezzawha biex ikun jista' jsir dan il-Ioghob fiha. Il-Ioghob tal-bocCi dam isir ghal bosta xhur fiha. Kien zmien il-Labour Government Fl-ahhar inbidlu c-cirkustanzi u ndahal il-Kunsill LokaIi wara t twaqqif taghhom Ii b'arrangamenti adatti wara pjanta peritali tal-Perit Joe Bugeja, iben ir restawratur Samwel, attrezzaha ghal gni~m pubbliku Din il-pjazza li ghaliha kont tasal minn toroq dojoq, ibda minn dik li minn Triq San Rokku, twasslek ghat-tempju, dik l-ohra Ii minn quddiem il-knisja Filjali ta' Sant'Antnin u Santa Katerina, tghaddi minn quddiem il-hanut tal-kafe' u tat-te' li kien immexxi minn Aquilina (maghrufbhala I-Pagun) twasslek quddiem pjazza spazjuza; kifukoll dik ir-rotta li minn Pjazza San Frangisk twasslek quddiem it-tempju, tghaddi minn quddiem hanut ta' skarpan faccata ta' Busuttil Jewellery u tghaddi minn quddiem il-hanut tal-kafe' li kien fil-kantuniera, immexxi minn certu Nurat. Fic-centru tal-pjazza quddiem il-hanut ta' Lorenzo Grima il-hutch (li zmien ilu kien ukoll restaurant) kien hemm il-hofra tal-gibjun fejn l-ilma li jaqa' minn fuq it-tempju Elenjan u minn bnadi ohra kien jingabar u nifakarhom itellghuh bil-bramel permezz tal-grab ja li fiha tiddendel it-tarjola ewlenija Fit-triq id-dejqa mnejn kienet tghaddi l-purCissjoni wara li tohrog mit-tempju kienet toqghod il biCCiera Dolores Pulo flimkien rna' zewgha, Patist. -

Fraud and Error in the Field of EU Social Security Coordination

Fraud and error in the field of EU social security coordination Reference year: 2015 Written by Yves Jorens, Dirk Gillis and Tiffany De Potter January – 2017 EUROPEAN COMMISSION Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion Unit D/2 European Commission B-1049 Brussels EUROPEAN COMMISSION Fraud and error in the field of EU social security coordination Reference year: 2015 Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion FreSsco (Contract No VC/2015/0940 ‘Network of Experts on intra-EU mobility – social security coordination and free movement of workers / Lot 1: Legal expertise in the field of social security coordination and free movement of workers’) 2016 Network Statistics FMSSFE This report was prepared in the framework of Contract No VC/2015/0940 ‘Network of Experts on intra-EU mobility – social security coordination and free movement of workers / Lot 2: Statistics and compilation of national data’. This contract was awarded to Network Statistics FMSSFE, an independent research network composed of expert teams from HIVA (KU Leuven), Milieu Ltd, IRIS (UGent), Szeged University and Eftheia bvba. Network Statistics FMSSFE is coordinated by HIVA. Authors: Prof Dr Yves Jorens, Professor of social security law and European social law, Director of IRIS│international research institute on social fraud, Ghent University Dirk Gillis, academic assistant, Coordinator of IRIS│international research institute on social fraud, Ghent University Tiffany De Potter, researcher at IRIS│international research institute on social fraud, Ghent University Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you). -

Forcepoint DLP Predefined Policies and Classifiers

Forcepoint DLP Predefined Policies and Classifiers Predefined Policies and Classifiers | Forcepoint DLP | v8.5.x For your convenience, Forcepoint DLP includes hundreds of predefined policies and content classifiers. ● Predefined policies help administrators quickly and easily define what type of content is considered a security breach at their organization. While choosing a policy or policy category, some items are set “off” by default. They can be activated individually in the Forcepoint Security Manager. ■ Data Loss Prevention policies, page 2 ■ Discovery policies, page 108 ● Predefined classifiers can be used to detect events and threats involving secured data. This article provides a list of all the predefined content classifiers that Forcepoint DLP provides for detecting events and threats involving secured data. This includes: ■ File-type classifiers ■ Script classifiers ■ Dictionaries ■ Pattern classifiers The predefined policies and classifiers are constantly being updated and improved. See Updating Predefined Policies and Classifiers for instructions on keeping policies and classifiers current. © 2017 Forcepoint LLC Data Loss Prevention policies Predefined Policies and Classifiers | Forcepoint DLP | v8.5.x Use the predefined data loss prevention policies to detect sensitive content, compliance violations, and data theft. For acceptable use policies, see: ● Acceptable Use, page 3 The content protection policies fall into several categories: ● Company Confidential and Intellectual Property (IP), page 4 ● Credit Cards, page 9 ● Financial -

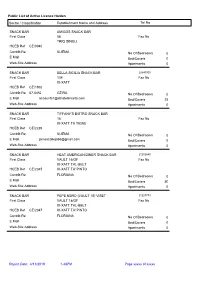

Public List of Active Licence Holders

Public List of Active Licence Holders Sector / Classification Establishment Name and Address Tel No SNACK BAR AMIGOS SNACK BAR First Class 56 Fax No TRIQ DINGLI HCEB Ref CE/0940 Contrib Ref SLIEMA No Of Bedrooms 0 E Mail Bed/Covers 0 Web-Site Address Apartments 0 SNACK BAR BELLA SICILIA SNACK BAR 22640000 First Class 134 Fax No IX-XATT HCEB Ref CE/1862 Contrib Ref 07-0452 GZIRA No Of Bedrooms 0 E Mail [email protected] Bed/Covers 25 Web-Site Address Apartments 0 SNACK BAR TIFFANY'S BISTRO SNACK BAR First Class 18 Fax No IX-XATT TA TIGNE HCEB Ref CE/2289 Contrib Ref SLIEMA No Of Bedrooms 0 E Mail [email protected] Bed/Covers 0 Web-Site Address Apartments 0 SNACK BAR HEAT AMERICAN DINER SNACK BAR 21252640 First Class VAULT 16/GF Fax No IX-XATT TAL-BELT HCEB Ref CE/2345 IX-XATT TA' PINTO Contrib Ref FLORIANA No Of Bedrooms 0 E Mail Bed/Covers 50 Web-Site Address Apartments 0 SNACK BAR PEPE NERO (VAULT 18) VISET 21227773 First Class VAULT 18/GF Fax No IX-XATT TAL-BELT HCEB Ref CE/2347 IX-XATT TA' PINTO Contrib Ref FLORIANA No Of Bedrooms 0 E Mail Bed/Covers 0 Web-Site Address Apartments 0 Report Date: 4/11/2019 1-48PM Page xxxxx of xxxxx Public List of Active Licence Holders Sector / Classification Establishment Name and Address Tel No SNACK BAR HAMMETT'S GASTRO BAR 21341116 First Class 33/34 Fax No IX-XATT TA TIGNE HCEB Ref CE/2481 Contrib Ref SLIEMA SLM 3011 No Of Bedrooms 0 E Mail Bed/Covers 25 Web-Site Address Apartments 0 SNACK BAR THE THIRSTY LAWYER SNACK BAR 79840068 First Class Fax No TRIQ ID-DEJQA HCEB Ref CE/3927