The Provisional Government of Azad Hind: Character and Objectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

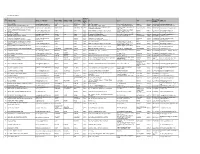

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

Chapter VI the LOCUS STANDI and SIGNIFICANCE of THE

Chapter VI THE LOCUS STANDI AND SIGNIFICANCE OF THE PROVISIONAL GOVERNMENT OFAZAD HIND The l.N.A. Government established by Netaji was a separate independent Government cf a separate and independent state - the Provisional Government of Free India. According to A.C.Chatterjee' there were some positive considerations for which Netaji formed the Provisional Government of Free India. They are as follows : (a) Attainment of Statehood and waging of the l.N.A. war as the war of a state against a State and not of an individual or a group against a state, or of a colonial dependency agains; an empire. (b) Provisional Government of Azad Hind would be a member of the international comit> of Nations and would thus acquire an international status. (c) As a tj'ue national war it would evoke greater public spirit and confidence, support and enthusiasm which was not expected in the case of an insurgency. (d) Territorial expansion in course of military operations and opening of new fronts accordingly. Expansion here did not mean annexation of territories of other countr es. It meant to bring the emancipated Indian territories under the l.N.A. Government. (e) A Pro^'isional Government was an absolute necessity as an organ through which the revoluionary organisation could secure manpower, money and material and also create a feeling of solidarity among the revolutionary forces. 174 (f) It also provided one central authority for coordinating the forces of the revolutionaries. This was one thing which was lacking in India's First War of Independence in 1857. (g) Besides, through alliance with other Governments it could secure special assistance from friendly countries. -

Section 124- Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 ASHOK KUMAR GOLCHHA 305 ASHOKA CHAMBERS ADARSHNAGAR HYDERABAD 500063 0000000000B9A0011390 36.00 2 ADAMALI ABDULLABHOY 20, SUKEAS LANE, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700001 0000000000B9A0050954 150.00 3 AMAR MANOHAR MOTIWALA DR MOTIWALA'S CLINIC, SUNDARAM BUILDING VIKRAM SARABHAI MARG, OPP POLYTECHNIC AHMEDABAD 380015 0000000000B9A0102113 12.00 4 AMRATLAL BHAGWANDAS GANDHI 14 GULABPARK NEAR BASANT CINEMA CHEMBUR 400074 0000000000B9A0102806 30.00 5 ARVIND KUMAR DESAI H NO 2-1-563/2 NALLAKUNTA HYDERABAD 500044 0000000000B9A0106500 30.00 6 BIBISHAB S PATHAN 1005 DENA TOWER OPP ADUJAN PATIYA SURAT 395009 0000000000B9B0007570 144.00 7 BEENA DAVE 703 KRISHNA APT NEXT TO POISAR DEPOT OPP OUR LADY REMEDY SCHOOL S V ROAD, KANDIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400067 0000000000B9B0009430 30.00 8 BABULAL S LADHANI 9 ABDUL REHMAN STREET 3RD FLOOR ROOM NO 62 YUSUF BUILDING MUMBAI 400003 0000000000B9B0100587 30.00 9 BHAGWANDAS Z BAPHNA MAIN ROAD DAHANU DIST THANA W RLY MAHARASHTRA 401601 0000000000B9B0102431 48.00 10 BHARAT MOHANLAL VADALIA MAHADEVIA ROAD MANAVADAR GUJARAT 362630 0000000000B9B0103101 60.00 11 BHARATBHAI R PATEL 45 KRISHNA PARK SOC JASODA NAGAR RD NR GAUR NO KUVO PO GIDC VATVA AHMEDABAD 382445 0000000000B9B0103233 48.00 12 BHARATI PRAKASH HINDUJA 505 A NEEL KANTH 98 MARINE DRIVE P O BOX NO 2397 MUMBAI 400002 0000000000B9B0103411 60.00 13 BHASKAR SUBRAMANY FLAT NO 7 3RD FLOOR 41 SEA LAND CO OP HSG SOCIETY OPP HOTEL PRESIDENT CUFFE PARADE MUMBAI 400005 0000000000B9B0103985 96.00 14 BHASKER CHAMPAKLAL -

Rrb Ntpc Top 100 Indian National Movement Questions

RRB NTPC TOP 100 INDIAN NATIONAL MOVEMENT QUESTIONS RRB NTPC TOP 100 INDIAN NATIONAL MOVEMENT QUESTIONS Stay Connected With SPNotifier EBooks for Bank Exams, SSC & Railways 2020 General Awareness EBooks Computer Awareness EBooks Monthly Current Affairs Capsules RRB NTPC TOP 100 INDIAN NATIONAL MOVEMENT QUESTIONS Click Here to Download the E Books for Several Exams Click here to check the topics related RRB NTPC RRB NTPC Roles and Responsibilities RRB NTPC ID Verification RRB NTPC Instructions RRB NTPC Exam Duration RRB NTPC EXSM PWD Instructions RRB NTPC Forms RRB NTPC FAQ Test Day RRB NTPC TOP 100 INDIAN NATIONAL MOVEMENT QUESTIONS 1. The Hindu Widows Remarriage act was Explanation: Annie Besant was the first woman enacted in which of the following year? President of Indian National Congress. She presided over the 1917 Calcutta session of the A. 1865 Indian National Congress. B. 1867 C. 1856 4. In which of the following movement, all the D. 1869 top leaders of the Congress were arrested by Answer: C the British Government? Explanation: The Hindu Widows' Remarriage Act A. Quit India Movement was enacted on 26 July 1856 that legalised the B. Khilafat Movement remarriage of Hindu widows in all jurisdictions of C. Civil Disobedience Movement D. Home Rule Agitation India under East India Company rule. Answer: A 2. Which movement was supported by both, The Indian National Army as well as The Royal Explanation: On 8 August 1942 at the All-India Indian Navy? Congress Committee session in Bombay, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi launched the A. Khilafat movement 'Quit India' movement. The next day, Gandhi, B. -

Trial of Indian National Army in Red Fort

© 2020 IJRAR June 2020, Volume 7, Issue 2 www.ijrar.org (E-ISSN 2348-1269, P- ISSN 2349-5138) Trial of Indian National Army in Red Fort; Simla Conference World War II Ends *Nagaratna.B.Tamminal, Asst Professor of History, Govt First Grade Womens’s College, Koppal. Abstract The present paper takes broad overview of trial of Indian National army as the World war II construction and presided over by lord Wavell. The Indian National Army trials (of captured members) began on November 5, 1945 at the Red Fort in Delhi, as three stalwarts of the Azad Hind Fauj — one a Muslim (Shahnawaz Khan), one a Hindu (Prem Sahgal) and one a Sikh (Gurbaksh Dhillon) — arrived at Subhas Bose’s "Chalo Delhi" destination in ironic ironclad circumstances. The commander-in-chief of the British Indian Army, Claude Auchinleck, had reported to his bosses on October 31 that the Indian Army would accept the INA trials as "the majority view is that they are all traitors". And he believed that stories about the INA’s returnee troops (who numbered no more than 23,000 survivors) would be overwhelmed by those of loyalist British Indian Army troops (numbering nearly a million) who would be returning to those same villages and towns. Hugh Toye, the British spy who delved into Subhas Bose’s life and became a grudging admirer, knew that there already were underlying problems with this view because the nature of demobilisation in Malaya had allowed the intermingling of INA prisoners and British Indian Army loyalists for too long. It had taken several months to evacuate the Indian troops, who were still the last ones to be repatriated after the British and Australian ones, so even the loyalist troops’ views and opinions about the war and nationalism were coloured. -

List of Nodal Officer

List of Nodal Officer Designa S.No tion of Phone (With Company Name EMAIL_ID_COMPANY FIRST_NAME MIDDLE_NAME LAST_NAME Line I Line II CITY PIN Code EMAIL_ID . Nodal STD/ISD) Officer 1 VIPUL LIMITED [email protected] PUNIT BERIWALA DIRT Vipul TechSquare, Golf Course Road, Sector-43, Gurgaon 122009 01244065500 [email protected] 2 ORIENT PAPER AND INDUSTRIES LTD. [email protected] RAM PRASAD DUTTA CSEC BIRLA BUILDING, 9TH FLOOR, 9/1, R. N. MUKHERJEE ROAD KOLKATA 700001 03340823700 [email protected] COAL INDIA LIMITED, Coal Bhawan, AF-III, 3rd Floor CORE-2,Action Area-1A, 3 COAL INDIA LTD GOVT OF INDIA UNDERTAKING [email protected] MAHADEVAN VISWANATHAN CSEC Rajarhat, Kolkata 700156 03323246526 [email protected] PREMISES NO-04-MAR New Town, MULTI COMMODITY EXCHANGE OF INDIA Exchange Square, Suren Road, 4 [email protected] AJAY PURI CSEC Multi Commodity Exchange of India Limited Mumbai 400093 0226718888 [email protected] LIMITED Chakala, Andheri (East), 5 ECOPLAST LIMITED [email protected] Antony Pius Alapat CSEC Ecoplast Ltd.,4 Magan Mahal 215, Sir M.V. Road, Andheri (E) Mumbai 400069 02226833452 [email protected] 6 ECOPLAST LIMITED [email protected] Antony Pius Alapat CSEC Ecoplast Ltd.,4 Magan Mahal 215, Sir M.V. Road, Andheri (E) Mumbai 400069 02226833452 [email protected] 7 NECTAR LIFE SCIENCES LIMITED [email protected] SUKRITI SAINI CSEC NECTAR LIFESCIENCES LIMITED SCO 38-39, SECTOR 9-D CHANDIGARH 160009 01723047759 [email protected] 8 ECOPLAST LIMITED [email protected] Antony Pius Alapat CSEC Ecoplast Ltd.,4 Magan Mahal 215, Sir M.V. Road, Andheri (E) Mumbai 400069 02226833452 [email protected] 9 SMIFS CAPITAL MARKETS LTD. -

Subhas Chandra Bose and the Alternative Politics in India Political Scenarios After Election

Subhas Chandra Bose and the Alternative Politics in India Political scenarios after election • The Congress victory in the 1937 election and the consequent formation of popular ministries changed the balance of power within the country vis-a-vis the colonial authorities. • The growth of left-wing parties and ideas led to a growing militancy within the nationalist ranks. • The stage seemed to be set for another resurgence of the nationalist movement. • Just at this time, the Congress had to undergo a crisis at the top — an occurrence which plagued the Congress every few years. Way of the crisis within Congress • Subhas Bose had been a unanimous choice as the President of the Congress in 1938. • In 1939, he decided to stand again — this time as the spokesperson of militant politics and radical groups. • Putting forward his candidature on 21 January 1939, Bose said that he represented the ‘new ideas, ideologies, problems and programmes’ that had emerged with ‘the progressive sharpening of the anti-imperialist struggle in India.’ • On 24 January, Sardar Patel, Rajendra Prasad, J.B. Kripalani and four other members of the Congress Working Committee issued a counter statement, declaring that the talk of ideologies, programmes and policies was irrelevant in the elections of a Congress president Result of the election • With the blessings of Gandhiji, Sardar Patel, Rajendra Prasad, J.B. Kripalani other leaders put up Pattabhi Sitaramayya as a candidate for the post. • Subhas Bose was elected on 29 January by 1580 votes against 1377. • Gandhiji declared that Sitaramayya’s defeat was ‘more mine than his.’ Apex of the crisis • But the election of Bose resolved nothing, it only brought the brewing crisis to a head at the Tripuri session of the Congress. -

Indian National Army

HIS5B09 HISTORY OF MODERN INDIA MODULE-4 TOPIC- INDIAN NATIONAL ARMY Prepared by Dr.Arun Thomas.M Assistant Professor Dept of History Little Flower College Guruvayoor Indian National Army • Indian National Army • The idea of the Indian National Army (INA) was first conceived in Malaya by Mohan Singh, an Indian officer of the British Indian Army, when he decided not to join the retreating British Army and instead turned to the Japanese for help. • The Japanese handed over the Indian prisoners of war (POWs) to Mohan Singh who tried to recruit them into an Indian National Army. • In1942, After the fall of Singapore, Mohan Singh further got 45,000 POWs into his sphere of influence. • 2 July 1943, Subhash Chandra Bose reached Singapore and gave the rousing war cry of ‘Dilli Chalo’ • Was made the President of Indian Independence League and soon became the supreme commander of the Indian National Army • Here he gave the slogan of Jai Hind • INA’s three Brigades were the Subhas Brigade, Gandhi Brigade and Nehru Brigade. • The women’s wing of the army was named after Rani Laxmibai. • INA marched towards Imphal after registering its victory over Kohima but after Japan’s surrender in 1945, INA failed in its efforts. • Under such circumstances, Subhash went to Taiwan & further on his way to Tokyo he died on 18 August 1945 in a plane crash. • Trial of the soldiers of INA was held at Red Fort in Delhi. • Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, Bhulabhai Desai, Kailash Nath Katju, Asaf Ali and Tej Bahadur Sapru fought the case on behalf of the soldiers. -

The Indian Struggle 1920-34

The Indian Struggle 1920-34 Subhas Chandra Bose www.subhaschandrabose.org January 2012 This book, first published in London in 1935, could be published in India only in 1948 since it was banned by the British Government. Mission Netaji is publishing this electronic version to facilitate a wider reach. The Indian Struggle Villeneuve (Vaud),Villa Olga, February 22,1935. Dear Mr. Subhas C. Bose, I duly received your volume “The Indian Struggle 1920-34”, which you were good enough to send me. I thank you for it and congratulate on it heartily. So interesting seemed the book to us that I ordered another copy so that my wife and sister should have one each. It is an indispensable work for the history of the Indian Movement. In it you show the best qualities of the historian: lucidity and high equity of mind. Rarely it happens that a man of action as you are is apt to judge without party spirit. …We, the men of thought, must each of us fight against the temptation, that befalls us in moments of fatigue and unsettledness, of repairing to a world beyond the battle called either God, or Art, or independence of Spirit, or those distant regions of the mystic soul. But fight we must, our duty lies on this side of the ocean, on the battle-ground of men… I sincerely wish that your health will speedily recover for the good of India that is in need of you and I beg you to believe in my cordial sympathy. Romain Rolland ii www.subhaschandrabose.org The Indian Struggle PREFACE Many are the defects that will be found in this book. -

Indian History

INDIAN HISTORY 1. With whom was a settlement for revenue made under the Mahalwari system ? (a) The Cultivators (b) The Zamindars (c) The Zamindars and Cultivators jointly (d) The village community as a whole 2.Who among the following established the swadeshi stream navigation company ? (a) A.D.Shroff (b) Harisarvottam Rao (c) V.O.Chidambaram Pillai (d) Walchand Hirachand 3.Who among the following made the first systematic critique of moderate politics in 1893-94 in a series of articles entiled “New Lamps for Old†? (a) Aurobindo Ghosh (b) Bal Gangadhar Tilak (c) Satish Chandra Mukherjee (d) Lala Lajpat 4.Who among the following was not a member of the states Reorganization Commission(SRC) appointed by pandit Jawaharlal Nehru ? (a) Justis Fazl Ali (b) Potti Sriramulu (c) K.M.Panikkar (d) Hridayanath Kunzru 5.Who among the following was the Sarbadhinayaka or the supreme leader of the Tamralipta jatiya sarkar,a parallel government set up by the nationalists in Tamluk during the Quit India Movement ? (a) Ajay Mukhopadhyay (b) Sushil Chandra Dhara (c) Matangini Hazra (d) Satish Chandra Samanta 6.Consider the following statements relating to the Civil Disobedience Movement : 1. By the Gandhi-Irwin pact,the congress agreed to suspend the Civil Disobedience Movement. 2. By the Gandhi-Irwin Pact,the Government Promised to release all political prisoners not convicted for violence. Which of the statements given above is/are correct ? (a) 1 only (b) 2 only (c) Both 1 and 2 (d) Neither 1 nor 2 7. In which year was the Treaty between independent India and china acknowledging China’s rights over Tibet was signed ? (a) 1949 (b) 1952 (c) 1954 (d) 1955 8. -

Indian National Movement-Indian National Army and Evolution of Princely States

9/27/2021 Indian National Movement Indian National Army and Evolution of Princely States- Examrace Examrace Indian National Movement-Indian National Army and Evolution of Princely States Get unlimited access to the best preparation resource for NTSE/Stage-II-National-Level : get questions, notes, tests, video lectures and more- for all subjects of NTSE/Stage- II-National-Level. Indian National Army The Foundation of Indian National Army In 1939 - 40, Subhash Chandra Bose dissatisfied with the political ideology of the Indian National Congress. On 16 - 17 January 1941, Netaji slipped out of his Elgin Road home in disguise and with an assumed name of Maulvi Ziauddin he reached Delhi and boarded the Frontier Mail for Peshawar. He reached Japan where he was received by Rash Behari Bose. Rash Behari Bose, one of the oldest Indian revolutionaries escaped from India after dropping a bomb on Lord Hardingein 1911. On 15th July 1942 the Indian National Army was formed as an organized body of troops. Capt. Mohan Singh became the General Officer Commanding of the Indian National Army. But, by December 1942, serious differences emerged between the INA officers led by Mohan Singh and the Japanese over the role that the INA was to play. Mohan Singh and Niranjan Singh Gill were arrested Netaji arrived in Singapore on 2 July 1943 and on the 25 August, he assumed Supreme Command of the USA. On 21 October 1943, Netaji formed the Provisional Government of Azad Hind. This Government was recognized by all the axis powers. Advance Headquarters of INA and the Provisional Government of Azad Hind headed by Netaji also moved to Rangoon.