Beitzel, Michael Lynn All Rights Reserved PLEASE NOTE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jlan Jjfrantfeto Jfogljorn

Dr. Robert Thornton Defies the Odds by Herman Cowan, Jr. other odds, as he went on to finish not This is the first of a series on the life only grammar school, but high school and philosophies of Dr. Robert A. and college. Thornton. Dr. Thornton is a (retired) As a child in Houston, Texas, Dr. professor of physics at the University Thornton attended grammar school of San Francisco. in a one room schoolhouse, where In this series Dr. Thornton will one instructor was responsible for emphasize the quality of education, teaching six grades, "if you can in this country and at the University of imagine that," retorts Thornton. San Francisco. After grammar school Thornton Part one of this series will feature transferred into the Houston public Dr. Thornton's background, his school system. "I attended the education, and his teaching colored high school,'' says Thornton. endeavors. "Our high school didn't have the When he was born on February 6, same curriculum as the white high 1897 (according to the bureau of schools," he claims. census) the odds were that he, "The wood and metal shops were because he was born a Negro, would excellent," says Thornton, "but we not even finish grammar school. Dr. had no good courses in the sciences, Robert A. Thornton defied those and Dr. Thornton will discuss the quality of education at USF. Continued on Page 3 jlan Jjfrantfeto Jfogljorn Volume 73 Number 14 University of San Francisco November 3, 1978 'Freedom Fighters' Oppose FA They've been called but Dr. Paul Lorton of the College of of curriculum, are still made by the student input in the decision-making "traditionalists" and they've been Business Administration, who Administration; these are decisions process, had its difficulties, but that called "The Freedom Fighters"; they recently resigned from the faculty which, in the University of California the faculty union was even less have been viewed with both scorn union, related several reasons for his system, for example, are made by the effective. -

Red Tape Delays Freedom BEHIND LENOX PHARMACY Most Modern, Affective and Efficient Method of • Carpet & Upholstry Cleaning SEEVIK Cleaning

v «.- 24 - EVENING HERALD, Sat., Feb. 7, 1981 Rain doesiiH deter NUUKHESIIR HAS ir friends of -Grasso BUSINESS DIRECTORY GUIDE FOR A SALADS HARTFORD (UPI) - Nearly 20,- Many people carried rosary beads ^FOR YOUR HOLIDAY VVEEKEND 000 mourners paid their last respects Related stories artd pic and cried, bowed their heads, or to Ella Tambiissl Grasso during a tures on paGe 20. made the sign of the cross as they MANCHESTER AND SURROUNDING 1 * • iMaMBnii round-the-clock tribute before the walked past the bier. An honor guard •ttartoarntre^MJ I • U T B 8 N . n « U M B W CMItT funeral mass at noon today for stood at attention while strains of at the ti9 ti< Connecticut’s former governor. classical music filled the Hall of the rignUiri file apprauHi df l children, Susane and Jim , were pre Friends, colleagues and many who Flags. It h aanivsraary o#tl The Marinated Mushroom, Inc. sent when the casket was opened at a VICINITY had never met Mrs. Grasso walked “Everybody just loved her,” said **(} £«il£« S it «£ & o a I of tA« private service. quickly past her open coffin today in Jean Susca, a Hartford baker. "She has been 86r1^ the 162 South M M S t • M M d h tM r. "The family decided she looked so a first-floor alcove of the Capitol. would say Tve got time for ilnuiiitfSa of ,the greater beautiful the caiket was going to be The doors were to be shut at 10 a.ih. everybody.’” Ires foif alfiKMt a cen- lofA Painting Problem? We’ll Helpl open to the public,” be said. -

SEC News Cover.Qxp

CoSIDA NEWS Intercollegiate Athletics News from Around the Nation May 22, 2007 College baseball changes looming Page 1 of 3 http://www.orlandosentinel.com/sports/local/orl-colbase2207may22,0,3111323.story? ADVERTISEMENTS coll=orl-sports-headlines College baseball changes looming Coaches fear new rules aimed at helping academic performance will end up hurting the game. Dave Curtis Sentinel Staff Writer May 22, 2007 South Carolina baseball Coach Ray Tanner fumes every time he hears about the changes. The NCAA, in an effort to boost the academic performance of players throughout college baseball, has approved changes Tanner thinks may harm the game he loves. "There are going to be issues with this," Tanner said on a Southeastern Conference coaches teleconference earlier this month. "And the caliber of play in college baseball is probably going to go down." "This" is a four-pronged overhaul of Division I college baseball rules approved in April by the NCAA Board of Directors and set to take effect for the 2008-09 academic year. Starting then, teams will face new standards for doling out their scholarships and new limits to the numbers on their rosters. Players must be academically eligible in late summer rather than mid-winter. And any player who transfers to another Division I school must sit out a year, a rule previously enforced only in football, basketball and men's ice hockey. The changes, recommended by a study group of coaches and administrators, are designed to increase the academic performance of D-I players. But they will affect almost every corner of the game, from summer leagues to high-school recruits to teams' budgets. -

College Basketball Review, 1953

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons La Salle Basketball Game Programs University Publications 2-10-1953 College Basketball Review, 1953 Unknown Author Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/basketball_game_programs Recommended Citation Unknown Author, "College Basketball Review, 1953" (1953). La Salle Basketball Game Programs. 2. https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/basketball_game_programs/2 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in La Salle Basketball Game Programs by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEMPLE DE PAUL LA SALLE ST. JOSEPH'S TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 10th, 1953 COLLEGE BASKETBALL REVIEW PRICE 25* Because Bulova is first in beauty, accuracy and value . more Americans tell time by Bulova than by any other fine watch in the world. Next time you buy a watch — for yourself or as a gift — choose the finest — Bulova! B u l o v a .. America’s greatest watch value! PRESIDENT 21 jewels Expansion Band $ 4 9 5 0 OFFICIAL TIMEPIECE NATIONAL INVITATION BASKETBALL TOURNAMENT TOP FLIGHT LOCAL PERFORMERS TOM GOLA, LA SALLE NORM GREKIN, LA SALLE JOHN KANE, TEMPLE ED GARRITY, ST. JOSEPH'S 3 Mikan ‘Held' to 24 points by St. Joseph’s in De Paul’s last visit to Hall Court G EO R G E MIKAN, the best of De Paul's basketball products and recognized as the court star of all times, has appeared on the Convention Hall boards a number of times as a pro star with the Minneapolis Lakers, but his college career included but one visit to the Hall. -

Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment

Shirley Papers 48 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title Research Materials Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment Capital Punishment 152 1 Newspaper clippings, 1951-1988 2 Newspaper clippings, 1891-1938 3 Newspaper clippings, 1990-1993 4 Newspaper clippings, 1994 5 Newspaper clippings, 1995 6 Newspaper clippings, 1996 7 Newspaper clippings, 1997 153 1 Newspaper clippings, 1998 2 Newspaper clippings, 1999 3 Newspaper clippings, 2000 4 Newspaper clippings, 2001-2002 Crime Cases Arizona 154 1 Cochise County 2 Coconino County 3 Gila County 4 Graham County 5-7 Maricopa County 8 Mohave County 9 Navajo County 10 Pima County 11 Pinal County 12 Santa Cruz County 13 Yavapai County 14 Yuma County Arkansas 155 1 Arkansas County 2 Ashley County 3 Baxter County 4 Benton County 5 Boone County 6 Calhoun County 7 Carroll County 8 Clark County 9 Clay County 10 Cleveland County 11 Columbia County 12 Conway County 13 Craighead County 14 Crawford County 15 Crittendon County 16 Cross County 17 Dallas County 18 Faulkner County 19 Franklin County Shirley Papers 49 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title 20 Fulton County 21 Garland County 22 Grant County 23 Greene County 24 Hot Springs County 25 Howard County 26 Independence County 27 Izard County 28 Jackson County 29 Jefferson County 30 Johnson County 31 Lafayette County 32 Lincoln County 33 Little River County 34 Logan County 35 Lonoke County 36 Madison County 37 Marion County 156 1 Miller County 2 Mississippi County 3 Monroe County 4 Montgomery County -

Illinois ... Football Guide

796.33263 lie LL991 f CENTRAL CIRCULATION '- BOOKSTACKS r '.- - »L:sL.^i;:f j:^:i:j r The person charging this material is re- sponsible for its return to the library from which it was borrowed on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutllotlen, UNIVERSITY and undarllnlnfl of books are reasons OF for disciplinary action and may result In dismissal from ILUNOIS UBRARY the University. TO RENEW CAll TEUPHONE CENTEK, 333-8400 AT URBANA04AMPAIGN UNIVERSITY OF ILtlNOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN APPL LiFr: STU0i£3 JAN 1 9 \m^ , USRARy U. OF 1. URBANA-CHAMPAIGN CONTENTS 2 Division of Intercollegiate 85 University of Michigan Traditions Athletics Directory 86 Michigan State University 158 The Big Ten Conference 87 AU-Time Record vs. Opponents 159 The First Season The University of Illinois 88 Opponents Directory 160 Homecoming 4 The Uni\'ersity at a Glance 161 The Marching Illini 6 President and Chancellor 1990 in Reveiw 162 Chief llliniwek 7 Board of Trustees 90 1990 lUinois Stats 8 Academics 93 1990 Game-by-Game Starters Athletes Behind the Traditions 94 1990 Big Ten Stats 164 All-Time Letterwinners The Division of 97 1990 Season in Review 176 Retired Numbers intercollegiate Athletics 1 09 1 990 Football Award Winners 178 Illinois' All-Century Team 12 DIA History 1 80 College Football Hall of Fame 13 DIA Staff The Record Book 183 Illinois' Consensus All-Americans 18 Head Coach /Director of Athletics 112 Punt Return Records 184 All-Big Ten Players John Mackovic 112 Kickoff Return Records 186 The Silver Football Award 23 Assistant -

Reslegal V02 1..3

*LRB09412802CSA47646r* SR0301 LRB094 12802 CSA 47646 r 1 SENATE RESOLUTION 2 WHEREAS, The members of the Senate of the State of Illinois 3 learned with sadness of the death of George Mikan, the original 4 "Mr. Basketball", of Arizona and formerly of Joliet, on June 1, 5 2005; and 6 WHEREAS, Mr. Mikan was born June 18, 1924, in Joliet; he 7 attended Joliet Catholic High School in Joliet, Quigley 8 Preparatory Seminary School in Chicago, and graduated from 9 DePaul University; he started studies to be a priest and was an 10 accomplished classical pianist; he was told he could never play 11 basketball because he wore glasses, but he persisted and proved 12 everyone wrong; and 13 WHEREAS, George Mikan, a 6-foot-10 giant of a man who 14 played basketball with superior coordination and a fierce 15 competitive spirit, was one of the prototypes for the 16 dominating tall players of later decades; and 17 WHEREAS, During George Mikan's college days at DePaul, he 18 revolutionized the game; he, along with fellow Hall of Famer 19 Bob Kurland, swatted away so many shots that in 1944 the NCAA 20 introduced a rule that prohibited goaltending; and 21 WHEREAS, He was a three-time All-America (1944, 1945, 1946) 22 and led the nation in scoring in 1945 and 1946; his 120 points 23 in three games led DePaul to the 1945 NIT championship; he 24 scored 1,870 points at DePaul and once tallied 53 against Rhode 25 Island State, a remarkable feat considering he single-handedly 26 outscored the entire Rhode Island State team; and 27 WHEREAS, In 1950, he was voted -

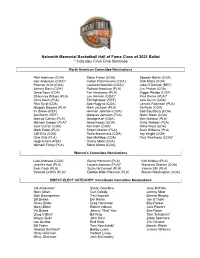

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Class of 2021 Ballot * Indicates First-Time Nominee

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Class of 2021 Ballot * Indicates First-Time Nominee North American Committee Nominations Rick Adelman (COA) Steve Fisher (COA) Speedy Morris (COA) Ken Anderson (COA)* Cotton Fitzsimmons (COA) Dick Motta (COA) Fletcher Arritt (COA) Leonard Hamilton (COA)* Jake O’Donnell (REF) Johnny Bach (COA) Richard Hamilton (PLA) Jim Phelan (COA) Gene Bess (COA) Tim Hardaway (PLA) Digger Phelps (COA) Chauncey Billups (PLA) Lou Henson (COA)* Paul Pierce (PLA)* Chris Bosh (PLA) Ed Hightower (REF) Jere Quinn (COA) Rick Byrd (COA) Bob Huggins (COA) Lamont Robinson (PLA) Muggsy Bogues (PLA) Mark Jackson (PLA) Bo Ryan (COA) Irv Brown (REF) Herman Johnson (COA) Bob Saulsbury (COA) Jim Burch (REF) Marques Johnson (PLA) Norm Sloan (COA) Marcus Camby (PLA) George Karl (COA) Ben Wallace (PLA) Michael Cooper (PLA)* Gene Keady (COA) Chris Webber (PLA) Jack Curran (COA) Ken Kern (COA) Willie West (COA) Mark Eaton (PLA) Shawn Marion (PLA) Buck Williams (PLA) Cliff Ellis (COA) Rollie Massimino (COA) Jay Wright (COA) Dale Ellis (PLA) Bob McKillop (COA) Paul Westhead (COA)* Hugh Evans (REF) Danny Miles (COA) Michael Finley (PLA) Steve Moore (COA) Women’s Committee Nominations Leta Andrews (COA) Becky Hammon (PLA) Kim Mulkey (PLA) Jennifer Azzi (PLA) Lauren Jackson (PLA)* Marianne Stanley (COA) Swin Cash (PLA) Suzie McConnell (PLA) Valerie Still (PLA) Yolanda Griffith (PLA)* Debbie Miller-Palmore (PLA) Marian Washington (COA) DIRECT-ELECT CATEGORY: Contributor Committee Nominations Val Ackerman* Simon Gourdine Jerry McHale Marv -

Renormalizing Individual Performance Metrics for Cultural Heritage Management of Sports Records

Renormalizing individual performance metrics for cultural heritage management of sports records Alexander M. Petersen1 and Orion Penner2 1Management of Complex Systems Department, Ernest and Julio Gallo Management Program, School of Engineering, University of California, Merced, CA 95343 2Chair of Innovation and Intellectual Property Policy, College of Management of Technology, Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland. (Dated: April 21, 2020) Individual performance metrics are commonly used to compare players from different eras. However, such cross-era comparison is often biased due to significant changes in success factors underlying player achievement rates (e.g. performance enhancing drugs and modern training regimens). Such historical comparison is more than fodder for casual discussion among sports fans, as it is also an issue of critical importance to the multi- billion dollar professional sport industry and the institutions (e.g. Hall of Fame) charged with preserving sports history and the legacy of outstanding players and achievements. To address this cultural heritage management issue, we report an objective statistical method for renormalizing career achievement metrics, one that is par- ticularly tailored for common seasonal performance metrics, which are often aggregated into summary career metrics – despite the fact that many player careers span different eras. Remarkably, we find that the method applied to comprehensive Major League Baseball and National Basketball Association player data preserves the overall functional form of the distribution of career achievement, both at the season and career level. As such, subsequent re-ranking of the top-50 all-time records in MLB and the NBA using renormalized metrics indicates reordering at the local rank level, as opposed to bulk reordering by era. -

Michael Jordan: a Biography

Michael Jordan: A Biography David L. Porter Greenwood Press MICHAEL JORDAN Recent Titles in Greenwood Biographies Tiger Woods: A Biography Lawrence J. Londino Mohandas K. Gandhi: A Biography Patricia Cronin Marcello Muhammad Ali: A Biography Anthony O. Edmonds Martin Luther King, Jr.: A Biography Roger Bruns Wilma Rudolph: A Biography Maureen M. Smith Condoleezza Rice: A Biography Jacqueline Edmondson Arnold Schwarzenegger: A Biography Louise Krasniewicz and Michael Blitz Billie Holiday: A Biography Meg Greene Elvis Presley: A Biography Kathleen Tracy Shaquille O’Neal: A Biography Murry R. Nelson Dr. Dre: A Biography John Borgmeyer Bonnie and Clyde: A Biography Nate Hendley Martha Stewart: A Biography Joann F. Price MICHAEL JORDAN A Biography David L. Porter GREENWOOD BIOGRAPHIES GREENWOOD PRESS WESTPORT, CONNECTICUT • LONDON Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Porter, David L., 1941- Michael Jordan : a biography / David L. Porter. p. cm. — (Greenwood biographies, ISSN 1540–4900) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-313-33767-3 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-313-33767-5 (alk. paper) 1. Jordan, Michael, 1963- 2. Basketball players—United States— Biography. I. Title. GV884.J67P67 2007 796.323092—dc22 [B] 2007009605 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2007 by David L. Porter All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2007009605 ISBN-13: 978–0–313–33767–3 ISBN-10: 0–313–33767–5 ISSN: 1540–4900 First published in 2007 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. -

2015-16 South Alabama Men's Basketball

www.USAJaguars.com 2015-16 @SouthAlaMBK SOUTH ALABAMA MEN’S BASKETBALL Game 2 • South Alabama Jaguars (1-0) at North Carolina State Wolfpack (0-1) November 15, 2015 • 5 p.m. CST • PNC Arena (19,700) • Raleigh, N.C. • Legends Classic South Alabama Quick Facts THE COACHES 2015-16 Schedule School Name ........................University of South Alabama South Alabama Matthew Graves (Butler, 1998) Date Opponent Result/Time Location ............................................................... Mobile, Ala. Record at USA: 24-41 (3rd year) 11/13 AUBURN-MONTGOMERY W 88-68 Founded ............................................................................1963 Overall Record: Same 11/15 at North Carolina State# 5 p.m. CST Enrollment .....................................................................16,462 President ..........Dr. Tony G. Waldrop (North Carolina ‘74) N.C. State Mark Gottfried (Alabama, 1987) 11/19 at LSU# 8 p.m. Athletics Director ....Dr. Joel Erdmann (S. Dakota St. ‘86) Record at NCST: 92-53 (4th year) 11/23 vs. Belmont# 3 p.m. CST National Affi liation .....................................NCAA Division I Overall Record: 370-208 (19th year) 11/24 vs. Kenn. State/IUPUI# 2/4:30 p.m. CST Conference .................................................................Sun Belt 11/28 at Denver 3 p.m. CST Home Court ..................................Mitchell Center (10,000) LAST GAME 11/30 SPRING HILL 7:05 p.m. Nickname.....................................................................Jaguars South Alabama rallied from a fi rst-half defi cit to defeat Auburn- 12/5 at Middle Tennessee 5 p.m. School Colors .......................................Blue, Red and White Montgomery 88-68. North Carolina State fell 85-68 at home to Wil- 12/14 SOUTHERN MISS 7:05 p.m. liam & Mary. 12/18 at Samford 7 p.m. • Coaching Staff • 12/22 RICE 7:05 p.m. -

2013-14 Men's Basketball Records Book

Award Winners Division I Consensus All-America Selections .................................................... 2 Division I Academic All-Americans By School ..................................................... 8 Division I Player of the Year ..................... 10 Divisions II and III Players of the Year ................................................... 12 Divisions II and III First-Team All-Americans by School ....................... 13 Divisions II and III Academic All-Americans by School ....................... 15 NCAA Postgraduate Scholarship Winners by School................................... 17 2 2013-14 NCAA MEN'S BASKETBALL RECORDS - DIVISION I CONSENSUS ALL-AMERICA SELECTIONS Division I Consensus All-America Selections 1917 1930 By Season Clyde Alwood, Illinois; Cyril Haas, Princeton; George Charley Hyatt, Pittsburgh; Branch McCracken, Indiana; Hjelte, California; Orson Kinney, Yale; Harold Olsen, Charles Murphy, Purdue; John Thompson, Montana 1905 Wisconsin; F.I. Reynolds, Kansas St.; Francis Stadsvold, St.; Frank Ward, Montana St.; John Wooden, Purdue. Oliver deGray Vanderbilt, Princeton; Harry Fisher, Minnesota; Charles Taft, Yale; Ray Woods, Illinois; Harry Young, Wash. & Lee. 1931 Columbia; Marcus Hurley, Columbia; Willard Hyatt, Wes Fesler, Ohio St.; George Gregory, Columbia; Joe Yale; Gilmore Kinney, Yale; C.D. McLees, Wisconsin; 1918 Reiff, Northwestern; Elwood Romney, BYU; John James Ozanne, Chicago; Walter Runge, Colgate; Chris Earl Anderson, Illinois; William Chandler, Wisconsin; Wooden, Purdue. Steinmetz, Wisconsin;