Austerity, Affluence and Discontent, 1951-1979

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dogfen Ir Cyhoedd Mr Richard Parry Jones, BA, MA

Dogfen ir Cyhoedd Mr Richard Parry Jones, BA, MA. Prif Weithredwr – Chief Executive CYNGOR SIR YNYS MÔN ISLE OF ANGLESEY COUNTY COUNCIL Swyddfeydd y Cyngor - Council Offices LLANGEFNI Ynys Môn - Anglesey LL77 7TW Ffôn / tel (01248) 752500 Ffacs / fax (01248) 750839 RHYBUDD O GYFARFOD NOTICE OF MEETING CYNGOR YMGYNGHOROL SEFYDLOG STANDING ADVISORY COUNCIL ON AR ADDYSG GREFYDDOL (CYSAG) RELIGIOUS EDUCATION (SACRE) DYDD GWENER, 28 MEHEFIN 2013 am FRIDAY, 28 JUNE at 2.00pm 2.00 o'r gloch YSTAFELL BWYLLGOR 1, COMMITTEE ROOM 1, COUNCIL SWYDDFEYDD Y CYNGOR, LLANGEFNI OFFICES, LLANGEFNI Ann Holmes 01248 752518 Swyddog Pwyllgor Committee Officer AELODA U / MEMBERS Cynghorwyr / Councillors:- Jim Evans, W.T.Hughes, Gwilym O.Jones, R.Llewelyn Jones, Alun Mummery, Dylan Rees Yr Enwadau Crefyddol/Religious Denominations Gwag/Vacant (Yr Eglwys yng Nghymru/The Church in Wales), Gwag/Vacant (Yr Eglwys Babyddol/The Catholic Church), Stephen Francis Roe (Yr Eglwys Fethodistaidd/The Methodist Church), Mr Rheinallt Thomas (Yr Eglwys Bresbyteraidd/Presbyterian Church of Wales), Mrs Catherine Jones (Undeb y Bedyddwyr/The Baptist Union of Wales), Yr Athro Euros Wyn Jones (Undeb yr Annibynwyr Cymraeg/Union of Welsh Independents) Athrawon/Teachers Mefys Edwards (Ysgol Syr Thomas Jones), Alison Jones (Ysgol Parch.Thomas Ellis), Bethan Ll.Jones (Ysgol y Graig), Mr Martin Wise (Ysgol Uwchradd Caergybi/Holyhead High School) Aelodau Cyfetholedig/Co -Opted Members Mrs Helen Roberts (Prifysgol Bangor University) Y Parch./Rev. Elwyn Jones (Cyngor yr Ysgolion Sul/Sunday Schools Council) R H A G L E N 1 CADEIRYDD Ethol Cadeirydd i’r CYSAG. 2 IS-GADEIRYDD Ethol Is-Gadeirydd i’r CYSAG. -

Celebrating 30 Years of Inspiring Future Engineers

WELSH ENGINEERING TALENT FOR THE FUTURE EESW WELSH ENGINEERING TALENT FOR THE FUTURE EESW STEM STEM Welsh Engineering Talent for the Future Cymru Issue Welsh Engineering Talent for the FutureSeptember Cymru talent No. 23 talent2019 Issue No. 18 THE JOURNAL OF THE ENGINEERING EDUCATION SCHEME WALES September 2014 TALENIssue No. 18 THE JOURNAL OF THE ENGINEERING EDUCATTION SCHEME WALES September 2014 INSIDE ADDRESSING SHORTFALL: 3 Cardiff University plays its part WINNER: Ysgol Plasmawr's Daniel 4 Clarke – Student of the Year ProspectiVE ENgiNeeriNG stUDENts at EESW'S HeaDStart CYMRU EVENT at SwaNsea UNIVersitY F1 IN SCHOOLS: Celebrating 30 years of Another excellent year 8 for teams in Wales inspiring future engineers ow in our 30th year, the ROBERT CATER targets and our ESF funding has NEngineering Education CEO, Engineering Education Scheme been extended and is currently Scheme Wales (EESW) currently Wales secure until 2021. engages with more than 8,000 Funding from the government students per year across both continues to ensure we can primary and secondary sectors. The foundation for the development of continue to operate across the scheme has grown significantly EESW was established. whole of Wales. JagUAR challenge: since it was first established Over the years the The ESF funding allowed Engaging young minds 12 by Austin Matthews in scheme grew and us to offer a broader range of in a fun and exciting way 1989 (see page 2) with developed to experiences to a wider 11-19 age funding from the involve larger range. Royal Academy of numbers and We continued with the sixth- Engineering. worked with form industry-linked project and Mr Matthews and an increasing added a range of activities for Key two other helpers 3oyears number of Stage 3 under the umbrella of established EESW as companies. -

List of Eligible Schools for Website 2019.Xlsx

England LEA/Establishment Code School/College Name Town 873/4603 Abbey College, Ramsey Ramsey 860/4500 Abbot Beyne School Burton‐on‐Trent 888/6905 Accrington Academy Accrington 202/4285 Acland Burghley School London 307/6081 Acorn House College Southall 931/8004 Activate Learning Oxford 307/4035 Acton High School London 309/8000 Ada National College for Digital Skills London 919/4029 Adeyfield School Hemel Hempstead 935/4043 Alde Valley School Leiston 888/4030 Alder Grange School Rossendale 830/4089 Aldercar High School Nottingham 891/4117 Alderman White School Nottingham 335/5405 Aldridge School ‐ A Science College Walsall 307/6905 Alec Reed Academy Northolt 823/6905 All Saints Academy Dunstable Dunstable 916/6905 All Saints' Academy, Cheltenham Cheltenham 301/4703 All Saints Catholic School and Technology College Dagenham 879/6905 All Saints Church of England Academy Plymouth 383/4040 Allerton Grange School Leeds 304/5405 Alperton Community School Wembley 341/4421 Alsop High School Technology & Applied Learning Specialist College Liverpool 358/4024 Altrincham College Altrincham 868/4506 Altwood CofE Secondary School Maidenhead 825/4095 Amersham School Amersham 380/4061 Appleton Academy Bradford 341/4796 Archbishop Beck Catholic Sports College Liverpool 330/4804 Archbishop Ilsley Catholic School Birmingham 810/6905 Archbishop Sentamu Academy Hull 306/4600 Archbishop Tenison's CofE High School Croydon 208/5403 Archbishop Tenison's School London 916/4032 Archway School Stroud 851/6905 Ark Charter Academy Southsea 304/4001 Ark Elvin Academy -

Austerity, Affluence and Discontent: Britain, 1951-1979

Austerity, Affluence and Discontent: britain, 1951-1979 Part 2: “Never had it so good” - What factors contributed to the economic recovery in the 1950s and 1960s? Source 1: A British family in the 1960s and the consumer items that could be found in their home 2 Austerity, Affluence and Discontent, 1951-1979: Part 2 Introduction: Harold Macmillan “Never Had It So Good” Source 2: Photograph of Harold Macmillan Harold Macmillan, the Conservative Prime Minister from 1957 to 1963, made a speech to a small crowd of people at Bedford Town’s football ground on 20 July 1957. The occasion was an event to mark twenty-five years continuous service of the Colonial Secretary Lennox-Boyd. It became famous because of a certain phrase that was used. The speech was reported in The Times newspaper on 22 July: Let us be frank about it: most of our people have never had it so good. Go around the country – go to the industrial towns, go to the farms – and you will see a state of prosperity such as we have never had in my lifetime, nor indeed ever in the history of this country. The phrase “never had it so good” is often misquoted as “You’ve never had it so good,” but the idea is a very simple one – life in the United Kingdom was better in the late 1950s than it had ever been because the country was more prosperous than it had ever been. Macmillan was much more cautious about the extent to which this was true than he has been given credit for, as he used the phrase “most of our people” in this context, to qualify his judgement. -

Caledi, Cyfoeth Ac Anniddigrwydd, 1951-1979

Caledi, Cyfoeth ac Anniddigrwydd, 1951-1979 Rhan 6: “Y gymdeithas wâr” – newid agwedd at awdurdod yn yr 1950au a’r 1960au Ffynhonnell 1 : Gorymdaith CND o Aldermaston i Lundain yn 19601 1 Andrew Marr, A History of Modern Britain (Llundain, 2009), tudalen 293. 2 Caledi, Cyfoeth ac Anniddigrwydd, 1951-1979: Rhan 6 A ddaeth y DU yn ‘gymdeithas fwy goddefol’ yn yr 1950au a’r 1960au? Agweddau tuag at gymdeithas Wrth ysgrifennu yn The Labour Case a gyhoeddwyd yn 1959, dywedodd yr AS Llafur Roy Jenkins, ‘Mae angen i’r Wladwriaeth wneud llai i gyfyngu ar ryddid personol’.2 Mae llawer o bobl wedi ystyried yr 1960au yn y DU fel cyfnod pan enillodd pobl Prydain lawer mwy o ryddid personol a chyfnod pan roedden nhw’n gallu symud y tu hwnt i gredoau a gwerthoedd cyfyngol yr adeg cyn y rhyfel. Credwyd bod ymlacio’r rheolyddion ar fywydau pobl yn yr 1960au wedi creu ‘cymdeithas fwy goddefol’, gan roi mwy o ryddid personol i bobl. Roedd y rhyddid newydd hwn yn berthnasol i nifer o agweddau gwahanol ar fywydau pobl. 1) Priodas, Teulu a Rhyw Enghreifftiau o weithgarwch y llywodraeth a arweiniodd at newid agweddau tuag at ryw a phriodas yn yr 1960au: sicrhawyd bod y bilsen atal cenhedlu ar gael i fenywod ar y Gwasanaeth Iechyd Gwladol, • i fenywod priod yn 1961 ac i bob menyw yn 1967; fe wnaeth Deddf Cynllunio Teulu 1967 sefydlu gwasanaethau cyngor atal cenhedlu roedd Deddf Erthyliadau 1967 yn gwneud erthyliad yn gyfreithlon pe bai dau feddyg yn • cytuno bod iechyd corfforol neu feddyliol y fam mewn perygl neu pe byddai’r plentyn yn cael ei eni ag anabledd corfforol neu feddyliol difrifol roedd Deddf Diwygio Ysgariad 1969 yn caniatáu ysgariad pe bai’r cwpl wedi byw ar • wahân am ddwy flynedd ac roedd y ddau eisiau ysgariad, neu pe bai’r cwpl wedi byw ar wahân am bum mlynedd a dim ond un person oedd eisiau dod â’r briodas i ben. -

A Report on Ysgol Uwchradd Caergybi Caergybi Ynys Mon LL65

A report on Ysgol Uwchradd Caergybi Caergybi Ynys Mon LL65 1NP Date of inspection: February 2012 by Estyn, Her Majesty’s Inspectorate for Education and Training in Wales During each inspection, inspectors aim to answer three key questions: Key Question 1: How good are the outcomes? Key Question 2: How good is provision? Key Question 3: How good are leadership and management? Inspectors also provide an overall judgement on the school’s current performance and on its prospects for improvement. In these evaluations, inspectors use a four-point scale: Judgement What the judgement means Many strengths, including significant Excellent examples of sector-leading practice Many strengths and no important areas Good requiring significant improvement Strengths outweigh areas for Adequate improvement Important areas for improvement Unsatisfactory outweigh strengths The report was produced in accordance with Section 28 of the Education Act 2005. Every possible care has been taken to ensure that the information in this document is accurate at the time of going to press. Any enquiries or comments regarding this document/publication should be addressed to: Publication Section Estyn Anchor Court Keen Road Cardiff CF24 5JW or by email to [email protected] This and other Estyn publications are available on our website: www.estyn.gov.uk © Crown Copyright 2012: This report may be re-used free of charge in any format or medium provided that it is re-used accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the report specified. A report on Ysgol Uwchradd Caergybi February 2012 Context Ysgol Uwchradd Caergybi is an 11-18 mixed English-medium comprehensive school maintained by Isle of Anglesey local authority. -

Engaging Girls in Engineering Careers Should Be at the Very Top of Our Agenda Says EESW

EESW EESW EESW STEM STEM talentWelsh Engineering Talent for the Future Cymru talentWelsh Engineering Talent for the Future Cymru STEM Issue No. 18 THE JOURNAL OF THE ENGINEERING EDUCATION SCHEME WALES SeptemberIssue No.2014 21 talentWelshWELSH Engineering ENGINEERINGIssue No. 18 Talent TALENTTHE JOURNAL FOR for OF THE THE the FUTURE ENGINEERING Future EDUCATION SCHEMEC WyALESmSeptemberru September 2017 2014 Issue No. 18 THE JOURNAL OF THE ENGINEERING EDUCATION SCHEME WALES September 2014 Tachyon Texas team Falcon Force team Engaging girls in engineering careers should be at the very top of our agenda says EESW There is a well-documented However, 39% of girls who At sixth-form level, the where girls show themselves to will represent Wales in the shortage of engineers in the Author's name were asked what subjects they barrier to taking up careers be high achievers. international final to be held UK. The Royal Academy of Where they are from enjoyed at school nominated in engineering is still the In each of the last three in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Engineering and Engineering design and technology, relatively low number of years, all-girl teams from You can read more about these UK, among others, have current engineering workforce computing and information females pursuing maths and Wales have won through amazing teams on page 6 and 7. conducted research that clearly in the UK: at only 9%, this is the technology. science at A-level. to the UK national finals A quote from the Tachyon highlights the shortfall. lowest percentage of female This research shows a strong However, lower down the age of the F1 Challenge. -

Remote Desktop Redirected Printer

England LEA/Establishment Code School/College Name Town 320/4001 Rushcroft Foundation School London 886/5425 The Malling School West Malling 935/4606 Ipswich Academy Ipswich 892/6906 Nottingham University Samworth Academy Nottingham 813/4002 Humber UTC Scunthorpe 816/8300 Askham Bryan College York 886/5458 Pent Valley Technology College Folkestone 879/8005 City College Plymouth Plymouth 886/5456 Northfleet Technology College Gravesend 350/6907 Kearsley Academy Bolton 343/8001 Southport College Southport 335/4057 Brownhills School Walsall 340/8002 Knowsley Community College Liverpool 909/4002 Energy Coast UTC Workington 881/4013 Sir Charles Kao Utc Harlow 887/8014 MidKent College Gillingham 371/4021 Armthorpe Academy Doncaster 358/4016 Wellacre Technology Academy Manchester 935/8003 Suffolk New College Ipswich 928/4010 Daventry UTC Daventry 886/4013 St Edmund's Catholic School Dover 860/5402 Stafford Manor High School Stafford 825/4002 The E-Act Burnham Park Academy Slough 885/8007 Heart of Worcestershire College Redditch 921/8000 The Isle of Wight College Newport 825/4067 The Mandeville School Aylesbury 861/4712 Ormiston Horizon Academy Stoke on Trent 881/6909 The Basildon Upper Academy Basildon 879/4000 UTC Plymouth Plymouth 891/4008 Kirkby College Nottingham 866/4000 UTC Swindon Swindon 309/4001 Tottenham UTC London 206/4000 Tech City College London 310/8002 Stanmore College Stanmore 884/4027 Earl Mortimer College and Sixth Form Centre Leominster 886/4012 The Leigh UTC Dartford 886/4065 The Holmesdale School Snodland 850/8600 Totton -

School Name DCSF School Code UCAS School Code Post Code

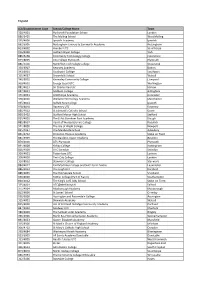

Contextual Data - Education Indicators for the 2014 admissions cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications Notes: 1. A 'WP Flag' (Widening Participation Flag) is produced if you meet the geo-demographic indicator or if you have been in care for more than three months. An additional contextual flag, a 'WP Plus Flag', is produced if you also meet at least one of the education indicators. 2. The education indicators are based on the combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 3. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does meet an education indicator. 4. 'No' in both columns means that a candidate from this school does not meet an education indicator. 5. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for that particular level of study. 6. Where both levels of study are reported as N/A, the school has not been included in this list. For a list of schools with no available data, please email [email protected]. For further information please refer to our website: www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata School Name DCSF School UCAS School Post Code School Level 2 School Level 3 Code Code Education Education Indicator Indicator Abbey Christian Brothers Grammar School 5420059 14099 BT34 2QN No No Abbey Christian Brothers Grammar School -

Public Document Pack Mr Richard Parry Jones, MA

Public Document Pack Mr Richard Parry Jones, MA. Prif Weithredwr/Chief Executive CYNGOR SIR YNYS MÔN ISLE OF ANGLESEY COUNTY COUNCIL Swyddfeydd y Cyngor - Council Offices LLANGEFNI Ynys Môn - Anglesey LL77 7TW Ffôn / tel (01248) 752500 Ffacs / fax (01248) 750839 RHYBUDD 0 GYFARFOD NOTICE OF MEETING CYNGOR YMGYNGHOROL SEFYDLOG AR STANDING ADVISORY COUNCIL ON ADDYSG GREFYDDOL (CYSAG) RELIGIOUS EDUCATION (SACRE) DYDD GWENER, 28 MEHEFIN 2013 am 2.00 FRIDAY, 28 JUNE 2013 at 2.00 pm o’r gloch yn prynhawn YSFTAFELL BWYLLGOR 1, SWYDDFEYDD Y COMMITTEE ROOM 1, COUNCIL OFFICES, CYNGOR, LLANGEFNI LLANGEFNI Ann Holmes 01248 752518 Swyddog Pwyllgor Committee Officer MEMBERS Cynghorwyr / Councillors: Jim Evans, W.T.Hughes, Gwilym O.Jones, R.Llewelyn Jones, Alun Mummery, Dylan Rees Yr Enwau Crefyddol / Religious Denominations Gwag/Vacant (Yr Eglwys yng Nghymru/The Church in Wales), Gwag/Vacant (Yr Eglwys Babyddol/The Catholic Church), Stephen Francis Roe (Yr Eglwys Fethodistaidd/The Methodist Church), Mr Rheinallt Thomas (Yr Eglwys Bresbyteraidd/Presbyterian Church of Wales),Mrs Catherine Jones (Undeb y Bedyddwyr/The Baptist Union of Wales), Yr Athro Euros Wyn Jones (Undeb yr Annibynwyr Cymraeg/Union of Welsh Independents) Athrawon/Teachers Mefys Edwards (Ysgol Syr Thomas Jones), Alison Jones (Ysgol Parch.Thomas Ellis), Bethan Ll.Jones (Ysgol y Graig), Mr Martin Wise (Ysgol Uwchradd Caergybi/Holyhead High School) Aelodau Cyfetholedig/Co-Opted Members Mrs Helen Roberts (Prifysgol Bangor University) Y Parch./Rev. Elwyn Jones (Cyngor yr Ysgolion Sul/Sunday Schools Council) A G E N D A 1 CHAIRPERSON To elect a Chairperson for the SACRE. 2 VICE-CHAIRPERSON To elect a Vice-Chairperson for the SACRE. -

Summary 2016.Xlsx

England LEA/School Code School Name Town 928/2022 DSLV E‐ACT Academy Daventry 840/4000 The North Durham Academy Stanley 909/4000 The Whitehaven Academy Cumbria 371/4000 Ash Hill Academy Doncaster 830/4000 Swanwick Hall School Alfreton 892/4000 Nottingham Girls' Academy Nottingham 928/4000 Weston Favell Academy Northampton 331/4000 Barr's Hill School and Community College Coventry 333/4000 Ormiston Forge Academy Cradley Heath 335/4000 Black Country UTC Walsall 926/4000 Nicholas Hamond Academy Swaffham 206/4000 Tech City College London 317/4000 Forest Academy Ilford 319/4000 Carshalton Boys Sports College Carshalton 825/4000 Chiltern Hills Academy Chesham 931/4000 Banbury Academy Banbury 868/4000 Desborough College Maidenhead 921/4000 Sandown Bay Academy Sandown 938/4000 Chichester High School for Boys Chichester 886/4000 St Augustine Academy Maidstone 887/4000 The Hundred of Hoo Academy Rochester 837/4000 LeAF Studio Bournemouth 878/4000 The Axe Valley Community College Axminster 879/4000 UTC Plymouth Plymouth 933/4000 Frome Community College Frome 880/4000 Torquay Academy Torquay 803/4000 Abbeywood Community School Bristol 865/4000 Abbeyfield School Chippenham 341/4001 Childwall Sports & Science Academy Liverpool 380/4001 Buttershaw Business and Enterprise College Bradford 831/4001 Merrill Academy Derby 830/4001 Alfreton Grange Arts College Alfreton 891/4001 Retford Oaks Academy Retford 855/4001 King Edward VII Science and Sport College Coalville 925/4001 University Academy Holbeach Spalding 928/4001 The Parker E‐ACT Academy Daventry 893/4001