Track Guide Updated 20 June

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eubrontes and Anomoepus Track

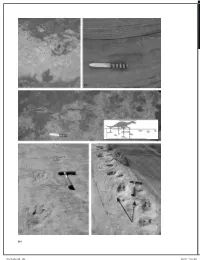

Sullivan, R.M. and Lucas, S.G., eds., 2016, Fossil Record 5. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 74. 345 EUBRONTES AND ANOMOEPUS TRACK ASSEMBLAGES FROM THE MIDDLE JURASSIC XIASHAXIMIAO FORMATION OF ZIZHONG COUNTY, SICHUAN, CHINA: REVIEW, ICHNOTAXONOMY AND NOTES ON PRESERVED TAIL TRACES LIDA XING1, MARTIN G. LOCKLEY2, GUANGZHAO PENG3, YONG YE3, JIANPING ZHANG1, MASAKI MATSUKAWA4, HENDRIK KLEIN5, RICHARD T. MCCREA6 and W. SCOTT PERSONS IV7 1School of the Earth Sciences and Resources, China University of Geosciences, Beijing 100083, China; -email: [email protected]; 2Dinosaur Trackers Research Group, University of Colorado Denver, P.O. Box 173364, Denver, CO 80217; 3 Zigong Dinosaur Museum, Zigong 643013, Sichuan, China; 4 Department of Environmental Sciences, Tokyo Gakugei University, Koganei, Tokyo 184-8501, Japan; 5 Saurierwelt Paläontologisches Museum Alte Richt 7, D-92318 Neumarkt, Germany; 6 Peace Region Palaeontology Research Centre, Box 1540, Tumbler Ridge, British Columbia V0C 2W0, Canada; 7 Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta 11455 Saskatchewan Drive, Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2E9, Canada Abstract—The Nianpanshan dinosaur tracksite, first studied in the 1980s, was designated as the type locality of the monospecific ichnogenus Jinlijingpus, and the source of another tridactyl track, Chuanchengpus, both presumably of theropod affinity. After the site was mapped in 2001, these two ichnotaxa were considered synonyms of Eubrontes and Anomoepus, respectively, the latter designation being the first identification of this ichnogenus in China. The assemblage indicates a typical Jurassic ichnofauna. The present study reinvestigates the site in the light of the purported new ichnospecies Chuanchengpus shenglingensis that was introduced in 2012. After re- evaluation of the morphological and extramorphological features, C. -

Oldest Known Dinosaurian Nesting Site and Reproductive Biology of the Early Jurassic Sauropodomorph Massospondylus

Oldest known dinosaurian nesting site and reproductive biology of the Early Jurassic sauropodomorph Massospondylus Robert R. Reisza,1, David C. Evansb, Eric M. Robertsc, Hans-Dieter Suesd, and Adam M. Yatese aDepartment of Biology, University of Toronto Mississauga, Mississauga, ON L5L 1C6, Canada; bRoyal Ontario Museum, Toronto, ON M5S 2C6, Canada; cSchool of Earth and Environmental Sciences, James Cook University, Townsville, 4811 QLD, Australia; dDepartment of Paleobiology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20013; and eBernard Price Institute for Palaeontological Research, University of the Witwatersrand, Wits 2050, Johannesburg, South Africa Edited by Steven M. Stanley, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI, and approved December 16, 2011 (received for review June 10, 2011) The extensive Early Jurassic continental strata of southern Africa clutches and recognition of the earliest known dinosaurian nesting have yielded an exceptional record of dinosaurs that includes complex at the Rooidraai locality. scores of partial to complete skeletons of the sauropodomorph Massospondylus, ranging from embryos to large adults. In 1976 an Results incomplete egg clutch including in ovo embryos of this dinosaur, Our work at the Rooidraai locality has yielded multiple in situ the oldest known example in the fossil record, was collected from clutches of eggs as well as fragmentary eggshell and bones, all from a road-cut talus, but its exact provenance was uncertain. An exca- a 2-m-thick interval of muddy siltstone 25 m from the top of the vation program at the site started in 2006 has yielded multiple in Lower Jurassic Upper Elliot Formation (“Stormberg Group,” situ egg clutches, documenting the oldest known dinosaurian Karoo Supergroup) (11). -

Download the Article

A couple of partially-feathered creatures about the The Outside Story size of a turkey pop out of a stand of ferns. By the water you spot a flock of bigger animals, lean and predatory, catching fish. And then an even bigger pair of animals, each longer than a car, with ostentatious crests on their heads, stalk out of the heat haze. The fish-catchers dart aside, but the new pair have just come to drink. We can only speculate what a walk through Jurassic New England would be like, but the fossil record leaves many hints. According to Matthew Inabinett, one of the Beneski Museum of Natural History’s senior docents and a student of vertebrate paleontology, dinosaur footprints found in the sedimentary rock of the Connecticut Valley reveal much about these animals and their environment. At the time, the land that we know as New England was further south, close to where Cuba is now. A system of rift basins that cradled lakes ran right through our region, from North Carolina to Nova Scotia. As reliable sources of water, with plants for the herbivores and fish for the carnivores, the lakes would have been havens of life. While most of the fossil footprints found in New England so far are in the lower Connecticut Valley, Dinosaur Tracks they provide a window into a world that extended throughout the region. According to Inabinett, the By: Rachel Marie Sargent tracks generally fall into four groupings. He explained that these names are for the tracks, not Imagine taking a walk through a part of New the dinosaurs that made them, since, “it’s very England you’ve never seen—how it was 190 million difficult, if not impossible, to match a footprint to a years ago. -

The Origin and Early Evolution of Dinosaurs

Biol. Rev. (2010), 85, pp. 55–110. 55 doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2009.00094.x The origin and early evolution of dinosaurs Max C. Langer1∗,MartinD.Ezcurra2, Jonathas S. Bittencourt1 and Fernando E. Novas2,3 1Departamento de Biologia, FFCLRP, Universidade de S˜ao Paulo; Av. Bandeirantes 3900, Ribeir˜ao Preto-SP, Brazil 2Laboratorio de Anatomia Comparada y Evoluci´on de los Vertebrados, Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales ‘‘Bernardino Rivadavia’’, Avda. Angel Gallardo 470, Cdad. de Buenos Aires, Argentina 3CONICET (Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Cient´ıficas y T´ecnicas); Avda. Rivadavia 1917 - Cdad. de Buenos Aires, Argentina (Received 28 November 2008; revised 09 July 2009; accepted 14 July 2009) ABSTRACT The oldest unequivocal records of Dinosauria were unearthed from Late Triassic rocks (approximately 230 Ma) accumulated over extensional rift basins in southwestern Pangea. The better known of these are Herrerasaurus ischigualastensis, Pisanosaurus mertii, Eoraptor lunensis,andPanphagia protos from the Ischigualasto Formation, Argentina, and Staurikosaurus pricei and Saturnalia tupiniquim from the Santa Maria Formation, Brazil. No uncontroversial dinosaur body fossils are known from older strata, but the Middle Triassic origin of the lineage may be inferred from both the footprint record and its sister-group relation to Ladinian basal dinosauromorphs. These include the typical Marasuchus lilloensis, more basal forms such as Lagerpeton and Dromomeron, as well as silesaurids: a possibly monophyletic group composed of Mid-Late Triassic forms that may represent immediate sister taxa to dinosaurs. The first phylogenetic definition to fit the current understanding of Dinosauria as a node-based taxon solely composed of mutually exclusive Saurischia and Ornithischia was given as ‘‘all descendants of the most recent common ancestor of birds and Triceratops’’. -

The First Record of Anomoepus Tracks from the Middle Jurassic of Henan Province, Central China

Historical Biology An International Journal of Paleobiology ISSN: 0891-2963 (Print) 1029-2381 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ghbi20 The first record of Anomoepus tracks from the Middle Jurassic of Henan Province, Central China Lida Xing, Nasrollah Abbassi, Martin G. Lockley, Hendrik Klein, Songhai Jia, Richard T. McCrea & W. Scott Persons IV To cite this article: Lida Xing, Nasrollah Abbassi, Martin G. Lockley, Hendrik Klein, Songhai Jia, Richard T. McCrea & W. Scott Persons IV (2016): The first record of Anomoepus tracks from the Middle Jurassic of Henan Province, Central China, Historical Biology, DOI: 10.1080/08912963.2016.1149480 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2016.1149480 Published online: 22 Feb 2016. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ghbi20 Download by: [Lida Xing] Date: 22 February 2016, At: 05:53 HISTORICAL BIOLOGY, 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2016.1149480 The first record of Anomoepus tracks from the Middle Jurassic of Henan Province, Central China Lida Xinga, Nasrollah Abbassib, Martin G. Lockleyc, Hendrik Kleind, Songhai Jiae, Richard T. McCreaf and W. Scott PersonsIVg aSchool of the Earth Sciences and Resources, China University of Geosciences, Beijing, China; bFaculty of Sciences, Department of Geology, University of Zanjan, Zanjan, Iran; cDinosaur Tracks Museum, University of Colorado Denver, Denver, CO, USA; dSaurierwelt Paläontologisches Museum, Neumarkt, Germany; eHenan Geological Museum, Henan Province, China; fPeace Region Palaeontology Research Centre, British Columbia, Canada; gDepartment of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Small, gracile mostly tridactyl tracks from the Middle Jurassic of Henan Province represent the first example Received 30 December 2015 of the ichnogenus Anomoepus from this region. -

A New Sauropodomorph Ichnogenus from the Lower Jurassic of Sichuan, China Fills a Gap in the Track Record

Historical Biology An International Journal of Paleobiology ISSN: 0891-2963 (Print) 1029-2381 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ghbi20 A new sauropodomorph ichnogenus from the Lower Jurassic of Sichuan, China fills a gap in the track record Lida Xing, Martin G. Lockley, Jianping Zhang, Hendrik Klein, Daqing Li, Tetsuto Miyashita, Zhongdong Li & Susanna B. Kümmell To cite this article: Lida Xing, Martin G. Lockley, Jianping Zhang, Hendrik Klein, Daqing Li, Tetsuto Miyashita, Zhongdong Li & Susanna B. Kümmell (2016) A new sauropodomorph ichnogenus from the Lower Jurassic of Sichuan, China fills a gap in the track record, Historical Biology, 28:7, 881-895, DOI: 10.1080/08912963.2015.1052427 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2015.1052427 Published online: 24 Jun 2015. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 95 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 2 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ghbi20 Download by: [University of Alberta] Date: 23 October 2016, At: 09:07 Historical Biology, 2016 Vol. 28, No. 7, 881–895, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2015.1052427 A new sauropodomorph ichnogenus from the Lower Jurassic of Sichuan, China fills a gap in the track record Lida Xinga*, Martin G. Lockleyb, Jianping Zhanga, Hendrik Kleinc, Daqing Lid, Tetsuto Miyashitae, Zhongdong Lif and Susanna B. Ku¨mmellg aSchool of the Earth Sciences and Resources, China University -

Dinotracks.Indb 358 1/22/16 11:23 AM Dinosaur Tracks in Eolian Strata: New Insights Into Track Formation, Walking Kinetics and Trackmaker Behavior 18

358 DinoTracks.indb 358 1/22/16 11:23 AM Dinosaur Tracks in Eolian Strata: New Insights into Track Formation, Walking Kinetics and Trackmaker Behavior 18 David B. Loope and Jesper Milàn Dinosaur tracks are abundant in wind-blown hooves of the bison deformed soft, laminated sediment – the Mesozoic deposits, but the nature of loose eolian sand perfect medium to preserve recognizable tracks. The next makes it difficult to determine how they are preserved. This windstorm buried the tracks. Today, the thick cover of grasses also raises the questions: Why would dinosaurs be walking protects the land surface so well that there are no soft, lami- around in dune fields in the first place? And, if they did go nated sediments for cattle to step on. And, if any tracks were, there, why would their tracks not be erased by the next wind somehow, to get formed, no moving sediment would be avail- storm? able to bury them. Mesozoic eolian sediments around the world, which have been the focus of a number of case studies Introduction in recent years, preserve the tracks of dinosaurs that walked on actively migrating sand dunes. This chapter summarizes Most dunes today form only in deserts and along shore- the known occurrences of dinosaur tracks in Mesozoic eo- lines – the only sandy land surfaces that are nearly devoid of lian strata and discusses their unique modes of preservation plants. Normally plants slow the wind at the ground surface and the anatomical and behavioral information about the enough that sand will not move even when the plant cover trackmakers that can be deduced from them. -

The Anatomy and Phylogenetic Relationships of Antetonitrus Ingenipes (Sauropodiformes, Dinosauria): Implications for the Origins of Sauropoda

THE ANATOMY AND PHYLOGENETIC RELATIONSHIPS OF ANTETONITRUS INGENIPES (SAUROPODIFORMES, DINOSAURIA): IMPLICATIONS FOR THE ORIGINS OF SAUROPODA Blair McPhee A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Science, University of the Witwatersrand, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science. Johannesburg, 2013 i ii ABSTRACT A thorough description and cladistic analysis of the Antetonitrus ingenipes type material sheds further light on the stepwise acquisition of sauropodan traits just prior to the Triassic/Jurassic boundary. Although the forelimb of Antetonitrus and other closely related sauropododomorph taxa retains the plesiomorphic morphology typical of a mobile grasping structure, the changes in the weight-bearing dynamics of both the musculature and the architecture of the hindlimb document the progressive shift towards a sauropodan form of graviportal locomotion. Nonetheless, the presence of hypertrophied muscle attachment sites in Antetonitrus suggests the retention of an intermediary form of facultative bipedality. The term Sauropodiformes is adopted here and given a novel definition intended to capture those transitional sauropodomorph taxa occupying a contiguous position on the pectinate line towards Sauropoda. The early record of sauropod diversification and evolution is re- examined in light of the paraphyletic consensus that has emerged regarding the ‘Prosauropoda’ in recent years. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I would like to express sincere gratitude to Adam Yates for providing me with the opportunity to do ‘real’ palaeontology, and also for gladly sharing his considerable knowledge on sauropodomorph osteology and phylogenetics. This project would not have been possible without the continued (and continual) support (both emotionally and financially) of my parents, Alf and Glenda McPhee – Thank you. -

GUIDE to the HITCHCOCK FAMILY PAPERS Scope and Content Note the Hitchcock Family Papers Have Been Received As Gifts by the Pocum

GUIDE TO THE HITCHCOCK FAMILY PAPERS Scope and Content Note The Hitchcock Family Papers have been received as gifts by the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association from several sources over many years. The collection numbers just over 400 items, and date between 1731 and 1979. The papers are those of and relating to the descendants of Luke [d. 1659] and Elizabeth (Gibbons) Hitchcock [d. 1696] of Wethersfield, Connecticut, through their sons John and Luke. The number that accompanies names in the notes below refers to the number assigned to the individual by George Sheldon in genealogical notes on the Hitchcock family in the second volume of his History of Deerfield [1895]. Many of the following biographical notes were selected from that source and from The Genealogy of the Hitchcock Family, compiled and published by Mrs. Edward Hitchcock, Jr. [Amherst, Mass., 1894]. Biographical Notes and Description of Series John Hitchcock4, son of Deacon John2 and Hannah (Chapin) Hitchcock, was born in Springfield, Mass., on April 13, 1670. On September 24, 1691 he married Mary Ball of Springfield and the couple had 11 children, one of whom is mentioned below. He received two shares of the township granted to survivors of the Falls Fight [Turners Falls, Mass.,1676] and their descendants and bequeathed them to his son John. He died in 1751, his widow in 1760. He is represented by four items: deeds to land in Brookfield and Springfield, Mass., dated 1731, a copy of his will, dated December 12, 1750, an account relating to the sale of his estate. Samuel Hitchcock7, son of Ensign John4 and Mary (Ball) Hitchcock, was born in Springfield, Mass., on June 9, 1717. -

The Early Jurassic Ornithischian Dinosaurian Ichnogenus Anomoepus

19 The Early Jurassic Ornithischian Dinosaurian Ichnogenus Anomoepus Paul E. Olsen and Emma C. Rainforth nomoepus is an Early Jurassic footprint genus and 19.2). Because skeletons of dinosaur feet were not produced by a relatively small, gracile orni- known at the time, he naturally attributed the foot- A thischian dinosaur. It has a pentadactyl ma- prints to birds. By 1848, however, he recognized that nus and a tetradactyl pes, but only three pedal digits some of the birdlike tracks were associated with im- normally impressed while the animal was walking. The pressions of five-fingered manus, and he gave the name ichnogenus is diagnosed by having the metatarsal- Anomoepus, meaning “unlike foot,” to these birdlike phalangeal pad of digit IV of the pes lying nearly in line with the axis of pedal digit III in walking traces, in combination with a pentadactyl manus. It has a pro- portionally shorter digit III than grallatorid (theropod) tracks, but based on osteometric analysis, Anomoepus, like grallatorids, shows a relatively shorter digit III in larger specimens. Anomoepus is characteristically bi- pedal, but there are quadrupedal trackways and less common sitting traces. The ichnogenus is known from eastern and western North America, Europe, and southern Africa. On the basis of a detailed review of classic and new material, we recognize only the type ichnospecies Anomoepus scambus within eastern North America. Anomoepus is known from many hundreds of specimens, some with remarkable preservation, showing many hitherto unrecognized details of squa- mation and behavior. . Pangea at approximately 200 Ma, showing the In 1836, Edward Hitchcock described the first of what areas producing Anomoepus discussed in this chapter: 1, Newark we now recognize as dinosaur tracks from Early Juras- Supergroup, eastern North America; 2, Karoo basin; 3, Poland; sic Newark Supergroup rift strata of the Connecticut 4, Colorado Plateau. -

Bifurculapes Hitchcock 1858: a Revision of the Ichnogenus

Document généré le 28 sept. 2021 10:48 Atlantic Geology Bifurculapes Hitchcock 1858 a revision of the ichnogenus Patrick R. Getty Volume 52, 2016 Résumé de l'article Les caractéristiques qui différencient la piste d’arthropode Bifurculapes des URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/ageo52art10 ichnogenres Lithographus et Copeza similaires sont la position, la disposition et l’orientation des traces à l’intérieur de la série. Parmi les cinq espèces de Aller au sommaire du numéro Bifurculapes originalement décrites, seules Bifurculapes laqueatus et Bifurculapes scolopendroideus sont ici reconnues. Les trois autres ichnoespèces sont considérées comme nomina dubia ou comme synonymes subjectifs plus Éditeur(s) récents de Bifurculapes laqueatus. Les deux nouveaux spécimens trouvés dans la formation du Jurassique précoce d’East Berlin dans le bassin de Hartford, à Atlantic Geoscience Society Holyoke, au Massachusetts, représentent seulement la seconde présence sans équivoque de l’ichnogenre à l’extérieur du bassin de Deerfield. À l’heure ISSN actuelle, Bifurculapes n’est associé qu’au Jurassique précoce. 0843-5561 (imprimé) [Traduit par la redaction] 1718-7885 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Getty, P. R. (2016). Bifurculapes Hitchcock 1858: a revision of the ichnogenus. Atlantic Geology, 52, 247–255. All rights reserved © Atlantic Geology, 2016 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. -

Bbm:978-94-017-9597-5/1.Pdf

Index A Arenicolites isp . , 21 , 46 , 64 , 70 , 85 , 88 Abarenicola pacifi ca , 105 Aristopentapodiscus , 373 Acanthichnus , 454 Artichnus , 21 , 43 , 93 Acropentapodiscus , 373 Artichnus pholeoides , 9 4 Acunaichnus dorregoensis , 390 Asaphoidichnus , 454 Ademosynidae , 195 Asencio Formation , 344 Adephagan beetles , 201 Asiatoceratodus , 238 Agua de la Peña Group , 192 Asteriacites , 9 , 21 , 43 , 44 , 66 Alcyonidiopsis , 280 , 283 Asteriacites lumbricalis , 42 , 67 Allocotichnus , 454 Asterosoma , 21 , 46 , 47 , 52 , 63 , 65 , 68 , 69 , 76 , Ameghinichnus , 372 , 373 78 , 85 , 89 , 95 Ameghinichnus patagonicu s , 372 Asterosoma coxii , 5 2 Amphibiopodiscus , 373 Asterosoma ludwigae , 5 2 Anachalcos mfwangani , 346 Asterosoma radiciformis , 5 2 Anchisauripus , 6 , 8 Asterosoma striata , 5 2 Ancorichnus , 4 5 Asterosoma surlyki , 5 2 Angulata Zone , 7 , 11 Atreipus , 6 , 8 , 147 Angulichnus , 454 Australopithecus , 413 Anomoepus , 6–8 Australopiths , 411 Anthropoidipes ameriborealis , 437 Avolatichnium , 192 Anyao Formation , 198 Azolla ferns , 202 Apatopus , 5 , 6 , 146 Arachnomorphichnus , 454 Arachnostega , 21 , 45 , 46 , 49 , 61 B Aragonitermes teruelensis , 335 Baissatermes lapideus , 335 Arariperhinus monnei , 335 Baissoferidae , 211 , 216 Archaeonassa , 34 , 62 , 223 , 454 Balanoglossites , 4 6 Archaeonassa fossulata , 192 Barberichnus bonaerensis , 304 Archeoentomichnus metapolypholeos , 320 Barrancapus , 5 Archosaur trackways , 6 Bathichnus paramoudrae , 8 0 Archosaurs , 137 , 138 , 140 , 143 , 145–147 , 160 Batrachopus , 6