Present Day Toxteth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Governors' News Spring 2010

Governor Services Courses for autumn 2015 Performance Related Pay Monday 21 September 10.00am to 12noon Ref: G15/42 or Monday 21 September 6.00pm to 8.00pm Ref: G15/43 Venue: Toxteth Annexe, Aigburth Road, L17 7BN The session will cover: The Governing Board’s responsibilities Monitoring the implementation of PRP Understanding the appeals process Presenters: Katie Smith and Kath Aistrop, School Employment Advisory Team Termly Meeting for Chairs Wednesday 23 September 6.00pm to 8.00pm Ref: G15/44 Venue: Toxteth Annexe, Aigburth Road, L17 7BN This meeting is open to Chairs, or representatives, of all Governing Bodies. Councillor Nick Small, Assistant Mayor of Liverpool & Cabinet Member - Education, Employment & Skills, Councillor Lana Orr, Mayoral Lead for Primary Schooling and Colette O’Brien, Director of Children’s Services will be present at the meeting. There will be a presentation of the Director's Items for the term followed by opportunities for discussion and questions. Cost: Free Ofsted Inspections Tuesday 29 September 6.00pm to 8.00pm Ref: G15/45 or Friday 02 October 10.00am to 12noon Ref: G15/46 Venue: Toxteth Annexe, Aigburth Road, L17 7BN The session will cover: The framework for inspections The inspection process How is Governance inspected? What will the Inspectors ask me? Presenter: Dave Cadwallader, Governor Services Officer 1 11111111 Termly Meeting for Clerks Friday 18 September 10.00am to 12noon Ref: G15/41 Venue: Toxteth Annexe, Aigburth Road, L17 7BN Our termly meeting for clerks to governing boards and/or committees includes briefings and discussion on current issues as well as an opportunity to share good practice and raise queries. -

Liverpool. (Kelly S

1 380 LIVERPOOL. (KELLY S • All"xander Bros. Llm. diamond merchants, jeweUers, silver Allan Diana (Mrs.), apartments, 102 Chatham street smiths &o. 66 Lord stnet .Allan George, coal dealer, lb'2A, Rosalind street, Kirkdale Alexander & Christie, commission merchants,& agents to the .Allan George, water inspector, 34 Horsley st. Mount Vemon North British Mercantile Insurance Co. 64 South Castle .Allan Henry, librarian Incorporated Law Society of Liver- street; T A " Consign, Liverpool " pool, 13 Union Court; res. 21 George's road Alexander Robert & Co. ship owners, I9 Tower buildings .Allan Henry, secretary The Rising Provident of Liverpool north, Water st. ; T A "Alrad, Liverpool" ; Tn 623 Limited ; res. 17 Ince avenue, Litherland Alexander & Co. cotton merchants, 142 & 144 The .Albany, Allan Henry, shipwright, 63 Gill street Oldhall street; T A " Rednaxela, Linrpool " .Allan James, assistant sec. London & Lancashire Fire Insur .Alexander .Alexander, commission agent,t. 23 Lombard ance Co. 45 Dale street; res. 13 Derby park, Rock Ferry chambers, Bixteth street .Allan James H. steam ship owner, see Allan Bros. & Co AlexanderBenjamin,grocer & provision dlr.21i-iSmithdown la. Alla.n James Henry, pharmaceutical chemist, 69 Breck road; Alexander Benjamin Graham, grocer & provision dealer, 86 Everton road & 40 William Henry street ; 139 Oakfield 146 North Hill street road, Everton & 31 West Derby rood; res. 26 Fitzclarence Alexander Chas. bookkeeper, 57 Cockburn st. Toxteth park street, Everton Alexander David, inspector of works, 45 Dorothy st.Edge hl Allan Job, furn. remover, 201 Westminster road, Kirkdale Alexander Dlonysius, mariner, 2 Vronhill st. Toxteth park .Allan John, clerk, 11 Bulwer street, Everton Alexandt:r Edward, professor of gymnastics, 116 Upper Allan John, painter, 58 Fernhill street, Toxtetb park H uskisson street Allan John, tinsmith, 3 Opie street, Everton Alexander Elias, commercial traveller, 94 Harrowby street, .Allan Joseph Barnes, shipwright, 5 Sterling street, Kirkdale Toxteth park .Allan Robert G. -

3 Restocking with Salmon, Trout and Freshwater Fish 80

North West fisheries report 2002 Item Type monograph Publisher Environment Agency North West Download date 07/10/2021 13:25:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/24896 I www.environment-agency.gov.uk • North West Fisheries Report 2002 Published by: Environment Agency Richard Fairclough House Knutsford Road Warrington WA4 1HG Tel: 01925 653999 Fax: 01925 415961 ISBN: 1844322076 © Environment Agency All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any other means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Environment Agency. NORTH WEST FISHERIES REPORT 2002 Contents Page Note on organisational changes 2 North West Region Fisheries and Recreation staff 3 Regional Fisheries Ecology, Recreation Advisory Committee 5 Consultative association contacts 6 Introduction 7 North Area Annual Report for 2002 Team report: South-West Cumbria 8 Team report: Eden 12 Team report: West Cumbria 14 Projects 15 Central Area Annual Report for 2002 Team reports 17 Projects 20 Survey reports 28 South Area annual report for 2002 Team reports 34 Survey reports 39 Projects 42 Note on Organisational Changes In the past year the Environment Agency has undergone major organisational changes. The area teams were previously organised in relation to work areas, e.g. we had an Area Fisheries Ecology and Recreation Manager, and a Fisheries team in each of our area offices. Since October 1, 2002 the old 'functional' structure has gone and the work is now split along geographic lines. The three areas now have two or more Environment Managers who are responsible for delivery of all Agency work (e.g. -

Coach Welcome Scheme

Coach welcome scheme LIVERPOOL COACH WELCOME There is secure coach parking at the Eco Coach groups can register for a special Visitor Centre alongside the park and ride Coach Welcome, which involves a personal scheme. This includes lounge, kitchen welcome to the city of Liverpool from one and shower facilities for drivers. of our enthusiastic coach hosts, the latest For more information visit www.visitsouthport.com information on what’s on, complimentary or contact Steve Christian on +44 (0)151 934 2319 maps, rest room and refreshment facilities. For drivers, there are coach drop-off WIRRAL COACH WELCOME and pick-up facilities, parking and traffic For a Mersey Ferries river cruise, park at information and refreshments. Woodside Ferry Terminal. Mersey Ferries links There are two locations: Liverpool Cathedral a number of exciting waterfront attractions in the city’s historic Hope Street Quarter, in Liverpool and Wirral, enabling you to and at Liverpool ONE bus station. create flexible days out for your group. We recommend booking at least 10 days in advance. Port Sunlight, a fascinating 19th century garden • LIVERPOOL CATHEDRAL village, is a very popular group travel destination +44 (0)151 702 7284 and home to both the Port Sunlight Museum and [email protected] Lady Lever Art Gallery. There is extensive free coach parking adjacent to the Lady Lever Art Gallery, with • LIVERPOOL ONE BUS STATION the village attractions easily accessible on foot. +44 (0)151 330 1354 [email protected] For more information about these and more visit www.visitwirral.com/visitor-info/group-travel SOUTHPORT COACH WELCOME Coach hosts are available from April to October to meet and greet coach visitors disembarking at the coach drop-off point on Lord Street, adjacent to The Atkinson. -

Student Guide to Living in Liverpool

A STUDENT GUIDE TO LIVING IN LIVERPOOL www.hope.ac.uk 1 LIVERPOOL HOPE UNIVERSITY A STUDENT GUIDE TO LIVING IN LIVERPOOL CONTENTS THIS IS LIVERPOOL ........................................................ 4 LOCATION ....................................................................... 6 IN THE CITY .................................................................... 9 LIVERPOOL IN NUMBERS .............................................. 10 DID YOU KNOW? ............................................................. 11 OUR STUDENTS ............................................................. 12 HOW TO LIVE IN LIVERPOOL ......................................... 14 CULTURE ....................................................................... 17 FREE STUFF TO DO ........................................................ 20 FUN STUFF TO DO ......................................................... 23 NIGHTLIFE ..................................................................... 26 INDEPENDENT LIVERPOOL ......................................... 29 PLACES TO EAT .............................................................. 35 MUSIC IN LIVERPOOL .................................................... 40 PLACES TO SHOP ........................................................... 45 SPORT IN LIVERPOOL .................................................... 50 “LIFE GOES ON SPORT AT HOPE ............................................................. 52 DAY AFTER DAY...” LIVING ON CAMPUS ....................................................... 55 CONTACT -

Widnes Appleton Village, Widnes

Service Name Address Postcode Monday 31st May 2021 Opening Hours Appleton Village Pharmacy - Widnes Appleton Village, Widnes WA8 6EQ 12:00- 14:00 Asda Pharmacy - West Lane - Runcorn West Lane, Runcorn WA7 2PY 09:00- 18:00 Asda Pharmacy - Widnes Road - Widnes Widnes Road, Widnes WA8 6AH 09:00- 18:00 Boots - Widnes Shopping Park - Widnes Unit 7, Widnes Shopping Park, High Street, Widnes WA8 7TN 10:00- 16:00 Tesco In Store Pharmacy - Ashley Retail Park - Widnes Ashley Gateway Retail Park, Lugsdale Road, Widnes WA8 7YT 09:00- 18:00 ASDA Pharmacy - Huyton Lane - Huyton 54-56 Huyton Lane, Huyton, Merseyside L36 7TX 09:00- 18:00 Boots - Cables Retail Park - Prescot Unit D, Block 4, Cables Retail Park, Prescot, Merseyside L34 5NQ 09:00- 18:00 Kingsway Pharmacy - Kingsway Parade - Huyton Ground Floor Shop, 5 Kingsway Parade, Huyton, Liverpool L36 2QA 10:00- 16:00 Tesco Instore Pharmacy - Cables Retail Park - Prescot Cables Retail Park, Steley Way, Prescot L34 5NQ 09:00- 18:00 Tops Pharmacy - Glovers Brow - Kirkby Units 5-6 Glovers Brow, Kirkby L32 2AE 14:00- 16:00 ASDA Pharmacy - Breck Road - Everton Breck Road, Everton, Liverpool L5 6PX 09:00- 18:00 ASDA Pharmacy - Smithdown Road - Wavertree 126 Smithdown Road, Wavertree, Liverpool L15 3JR 09:00- 18:00 ASDA Pharmacy - Speke Hall Road - Hunts Cross Unit 20, Hunts Cross Shopping Centre, Speke Hall Road, Hunts L24 9WA 09:00- Cross, Liverpool 18:00 ASDA Pharmacy - Utting Avenue - Walton Utting Avenue, Walton, Liverpool L4 9XU 09:00- 18:00 Boots - Church Street - Liverpool 9-11 Church Street, Liverpool -

Liverpool District Local Integrated Risk Management Plan 2010/2011

APPENDIX B (CFO/057/10) Liverpool District Local Integrated Risk Management Plan 2010/2011 Contents 1. Foreword 2. Our Purpose, Aims and Core Values 3. Introduction 4. Liverpool’s Story of Place 5. Our Plans to Reduce Risk and to Address Local Priorities in Liverpool • Liverpool Community Gyms • Liverpool East Community Garden • Street Based Teams • Liverpool South Speke Community Gardens • Neighbourhood Firefighters • TAG Rugby • Healthy Watch • Generic Action Point - Fitness and Health • Generic Action Point – Corporate Social Responsibility • Generic Action Point - Carbon Footprint • Generic Action Point – Equality and Diversity 6. Conclusion 7. Appendix A Merseyside Fire & Rescue Service Local Performance Indicators. 8. Appendix B Liverpool Local Area Priority National Indicators 9. Appendix C Merseyside Fire & Rescue Service Liverpool District Management Structure. Contact Information Liverpool Management Team Position Name Email Contact District Manager Dave Mottram [email protected] 0151 296 4714 District Manager Richard Davis [email protected] 0151 296 4622 NM East Kevin Johnson NM South Ken Ross NM SouthCentral Sara Lawton NM North+City Paul Murphy NM Alt Valley Kevin Firth Liverpool 1st Rob Taylor Liverpool Fire Stations Station Address Contact 10 – Kirkdale Studholme Street, Liverpool, L20 8EQ 0151 296 5375 11 – City Centre St Anne Street, Liverpool, L3 3DS 0151 296 6250 12 – Low Hill West Derby Road, Liverpool, L6 2AE 0151 296 5415 13 – Allerton Mather Avenue, Allerton, Liverpool, L18 6HE 0151 296 -

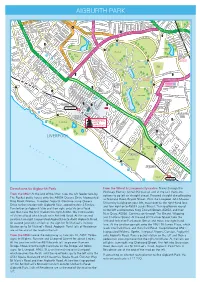

Aigburth Park

G R N G A A O A T D B N D LM G R R AIGBURTHA PARK 5 P R I R M B T 5 R LTAR E IN D D GR G 6 R 1 I Y CO O Superstore R R O 5 V Y 7 N D 2 R S E 5 E E L T A C L 4 A Toxteth Park R E 0 B E P A E D O Wavertree H S 7 A T A L S 8 Cemetery M N F R O Y T A Y E A S RM 1 R N Playground M R S P JE N D K V 9 G E L A IC R R K E D 5 OV N K R R O RW ST M L IN E O L A E O B O A O P 5 V O W IN A U C OL AD T R D A R D D O E A S S 6 P N U E Y R U B G U E E V D V W O TL G EN T 7 G D S EN A V M N N R D 1 7 I B UND A A N E 1 N L A 5 F R S V E B G G I N L L S E R D M A I T R O N I V V S R T W N A T A M K ST E E T V P V N A C Y K V L I V A T A D S R G K W I H A D H K A K H R T C N F I A R W IC ID I A P A H N N R N L L E A E R AV T D E N W S S L N ARDE D A T W D T N E A G K A Y GREENH H A H R E S D E B T B E M D T G E L M O R R Y O T V I N H O O O A D S S I T L M L R E T A W V O R K E T H W A T C P U S S R U Y P IT S T Y D C A N N R I O C H R C R R N X N R RL T E TE C N A DO T E E N TH M 9 A 56 G E C M O U 8 ND R S R R N 0 2 A S O 5 R B L E T T D R X A A L O R BE E S A R P M R Y T Y L A A C U T B D H H S M K RT ST S E T R O L E K I A H N L R W T T H D A L RD B B N I W A LA 5175 A U W I R T Y P S R R I F H EI S M S O Y C O L L T LA A O D O H A T T RD K R R H T O G D E N D L S S I R E DRI U V T Y R E H VE G D A ER E H N T ET A G L Y R EFTO XT R E V L H S I S N DR R H D E S G S O E T T W T H CR E S W A HR D R D Y T E N V O D U S A O M V B E N I O I IR R S N A RIDG N R B S A S N AL S T O T L D K S T R T S V T O R E T R E O A R EET E D TR K A D S LE T T E P E TI S N -

Liverpool Historic Settlement Study

Liverpool Historic Settlement Study Merseyside Historic Characterisation Project December 2011 Merseyside Historic Characterisation Project Museum of Liverpool Pier Head Liverpool L3 1DG © Trustees of National Museums Liverpool and English Heritage 2011 Contents Introduction to Historic Settlement Study..................................................................1 Aigburth....................................................................................................................4 Allerton.....................................................................................................................7 Anfield.................................................................................................................... 10 Broadgreen ............................................................................................................ 12 Childwall................................................................................................................. 14 Clubmoor ............................................................................................................... 16 Croxteth Park ......................................................................................................... 18 Dovecot.................................................................................................................. 20 Everton................................................................................................................... 22 Fairfield ................................................................................................................. -

Reconstructing Public Housing Liverpool’S Hidden History of Collective Alternatives

Reconstructing Public Housing Liverpool’s hidden history of collective alternatives Reconstructing Public Housing Liverpool’s hidden history of collective alternatives Reconstructing Public Housing Matthew Thompson LIVERPOOL UNIVERSITY PRESS First published 2020 by Liverpool University Press 4 Cambridge Street Liverpool L69 7ZU Copyright © 2020 Matthew Thompson The right of Matthew Thompson to be identified as the author of this book has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication data A British Library CIP record is available ISBN 978-1-78962-108-2 paperback eISBN 978-1-78962-740-4 Typeset by Carnegie Book Production, Lancaster An Open Access edition of this book is available on the Liverpool University Press website and the OAPEN library. Contents Contents List of Figures ix List of Abbreviations x Acknowledgements xi Prologue xv Part I Introduction 1 Introducing Collective Housing Alternatives 3 Why Collective Housing Alternatives? 9 Articulating Our Housing Commons 14 Bringing the State Back In 21 2 Why Liverpool of All Places? 27 A City of Radicals and Reformists 29 A City on (the) Edge? 34 A City Playing the Urban Regeneration Game 36 Structure of the Book 39 Part II The Housing Question 3 Revisiting -

Using Proximate Real Estate to Fund England's Nineteenth Century

Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes An International Quarterly ISSN: 1460-1176 (Print) 1943-2186 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tgah20 Using proximate real estate to fund England’s nineteenth century pioneering urban parks: viable vehicle or mendacious myth? John L. CromptonJOHN L. CROMPTON To cite this article: John L. CromptonJOHN L. CROMPTON (2019): Using proximate real estate to fund England’s nineteenth century pioneering urban parks: viable vehicle or mendacious myth?, Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes, DOI: 10.1080/14601176.2019.1638164 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14601176.2019.1638164 Published online: 25 Jul 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 23 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tgah20 Using proximate real estate to fund England’s nineteenth century pioneering urban parks: viable vehicle or mendacious myth? john l. crompton It could reasonably be posited that large public urban parks are one of Parliament which was a cumbersome and costly method.1 There were only England’s best ideas and one of its most widely adopted cultural exports. two alternatives. First, there were voluntary philanthropic subscription cam- They were first conceived, nurtured and implemented in England. From paigns that, for example, underwrote Victoria Park which opened in Bath in there they spread to the other UK countries, to the USA, to Commonwealth 1830; Queen’s Park, Philips Park and Peel Park in the Manchester area in the nations, and beyond. -

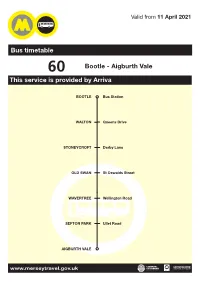

60 Bootle - Aigburth Vale This Service Is Provided by Arriva

Valid from 11 April 2021 Bus timetable 60 Bootle - Aigburth Vale This service is provided by Arriva BOOTLE Bus Station WALTON Queens Drive STONEYCROFT Derby Lane OLD SWAN St Oswalds Street WAVERTREE Wellington Road SEFTON PARK Ullet Road AIGBURTH VALE www.merseytravel.gov.uk What’s changed? From Bootle to Aigburth, Mondays-Fridays and Saturdays journeys have minor time changes. The last journey from Bootle Bus Station on Saturday is now half an hour later at 2315. Aigburth to Bootle service hasn’t changed. Any comments about this service? If you’ve got any comments or suggestions about the services shown in this timetable, please contact the bus company who runs the service: Arriva North West 73 Ormskirk Road, Aintree, Liverpool, L9 5AE 0344 800 44 11 or contact us at Merseytravel: By e-mail [email protected] By phone 0151 330 1000 In writing PO Box 1976, Liverpool, L69 3HN Need some help or more information? For help planning your journey, call 0151 330 1000, open 0800-2000, 7 days a week. You can visit one of our Travel Centres across the Merseytravel network to get information about all public transport services. To find out opening times, phone us on 0151 330 1000. Our website contains lots of information about public transport across Merseyside. You can visit our website at www.merseytravel.gov.uk Bus services may run to different timetables during bank and public holidays, so please check your travel plans in advance. Large print timetables We can supply this timetable in another format, such as large print.