How to Lay out a Very Large Garden Indeed: Edward Kemp's Liverpool

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NACS Code Practice Name N82054 Abercromby Health Centre N82086

NACS Code Practice Name N82054 Abercromby Health Centre N82086 Abingdon Family Health Centre N82053 Aintree Park Group Practice N82095 Albion Surgery N82103 Anfield Group Practice N82647 Anfield Health - Primary Care Connect N82094 Belle Vale Health Centre N82067 Benim MC N82671 Bigham Road MC N82078 Bousfield Health Centre N82077 Bousfield Surgery N82117 Brownlow Group Practice N82093 Derby Lane MC N82033 Dingle Park Practice N82003 Dovecot HC N82651 Dr Jude’s Practice Stanley Medical Centre N82646 Drs Hegde and Jude's Practice N82662 Dunstan Village Group Practice N82065 Earle Road Medical Centre N82024 West Derby Medical Centre N82022 Edge Hill MC N82018 Ellergreen Medical Centre N82113 Fairfield General Practice N82676 Fir Tree Medical Centre N82062 Fulwood Green MC N82050 Gateacre Medical Centre N82087 Gillmoss Medical Centre N82009 Grassendale Medical Practice N82669 Great Homer Street Medical Centre N82090 Green Lane MC N82079 Greenbank Rd Surgery N82663 Hornspit MC N82116 Hunts Cross Health Centre N82081 Islington House Surgery N82083 Jubilee Medical Centre N82101 Kirkdale Medical Centre N82633 Knotty Ash MC N82014 Lance Lane N82019 Langbank Medical Centre N82110 Long Lane Medical Centre N82001 Margaret Thompson M C N82099 Mere Lane Practice N82655 Moss Way Surgery N82041 Oak Vale Medical Centre N82074 Old Swan HC N82026 Penny Lane Surgery N82089 Picton Green N82648 Poulter Road Medical Centre N82011 Priory Medical Centre N82107 Queens Drive Surgery N82091 GP Practice Riverside N82058 Rock Court Surgery N82664 Rocky Lane Medical -

Coach Welcome Scheme

Coach welcome scheme LIVERPOOL COACH WELCOME There is secure coach parking at the Eco Coach groups can register for a special Visitor Centre alongside the park and ride Coach Welcome, which involves a personal scheme. This includes lounge, kitchen welcome to the city of Liverpool from one and shower facilities for drivers. of our enthusiastic coach hosts, the latest For more information visit www.visitsouthport.com information on what’s on, complimentary or contact Steve Christian on +44 (0)151 934 2319 maps, rest room and refreshment facilities. For drivers, there are coach drop-off WIRRAL COACH WELCOME and pick-up facilities, parking and traffic For a Mersey Ferries river cruise, park at information and refreshments. Woodside Ferry Terminal. Mersey Ferries links There are two locations: Liverpool Cathedral a number of exciting waterfront attractions in the city’s historic Hope Street Quarter, in Liverpool and Wirral, enabling you to and at Liverpool ONE bus station. create flexible days out for your group. We recommend booking at least 10 days in advance. Port Sunlight, a fascinating 19th century garden • LIVERPOOL CATHEDRAL village, is a very popular group travel destination +44 (0)151 702 7284 and home to both the Port Sunlight Museum and [email protected] Lady Lever Art Gallery. There is extensive free coach parking adjacent to the Lady Lever Art Gallery, with • LIVERPOOL ONE BUS STATION the village attractions easily accessible on foot. +44 (0)151 330 1354 [email protected] For more information about these and more visit www.visitwirral.com/visitor-info/group-travel SOUTHPORT COACH WELCOME Coach hosts are available from April to October to meet and greet coach visitors disembarking at the coach drop-off point on Lord Street, adjacent to The Atkinson. -

Student Guide to Living in Liverpool

A STUDENT GUIDE TO LIVING IN LIVERPOOL www.hope.ac.uk 1 LIVERPOOL HOPE UNIVERSITY A STUDENT GUIDE TO LIVING IN LIVERPOOL CONTENTS THIS IS LIVERPOOL ........................................................ 4 LOCATION ....................................................................... 6 IN THE CITY .................................................................... 9 LIVERPOOL IN NUMBERS .............................................. 10 DID YOU KNOW? ............................................................. 11 OUR STUDENTS ............................................................. 12 HOW TO LIVE IN LIVERPOOL ......................................... 14 CULTURE ....................................................................... 17 FREE STUFF TO DO ........................................................ 20 FUN STUFF TO DO ......................................................... 23 NIGHTLIFE ..................................................................... 26 INDEPENDENT LIVERPOOL ......................................... 29 PLACES TO EAT .............................................................. 35 MUSIC IN LIVERPOOL .................................................... 40 PLACES TO SHOP ........................................................... 45 SPORT IN LIVERPOOL .................................................... 50 “LIFE GOES ON SPORT AT HOPE ............................................................. 52 DAY AFTER DAY...” LIVING ON CAMPUS ....................................................... 55 CONTACT -

Liverpool City Region Visitor Economy Strategy to 2020

LiverpooL City region visitor eConomy strategy to 2020 oCtober 2009 Figures updated February 2011 The independent economic model used for estimating the impact of the visitor economy changed in 2009 due to better information derived about Northwest day visitor spend and numbers. All figures used in this version of the report have been recalibrated to the new 2009 baseline. Other statistics have been updated where available. Minor adjustments to forecasts based on latest economic trends have also been included. All other information is unchanged. VisiON: A suMMAry it is 2020 and the visitor economy is now central World Heritage site, and for its festival spirit. to the regeneration of the Liverpool City region. it is particularly famous for its great sporting the visitor economy supports 55,000 jobs and music events and has a reputation for (up from 41,000 in 2009) and an annual visitor being a stylish and vibrant 24 hour city; popular spend of £4.2 billion (up from £2.8 billion). with couples and singles of all ages. good food, shopping and public transport underpin Liverpool is now well established as one of that offer and the City region is famous for its europe’s top twenty favourite cities to visit (39th friendliness, visitor welcome, its care for the in 2008). What’s more, following the success of environment and its distinctive visitor quarters, its year as european Capital of Culture, the city built around cultural hubs. visitors travel out continued to invest in its culture and heritage to attractions and destinations in other parts of and destination marketing; its decision to use the City region and this has extended the length the visitor economy as a vehicle to address of the short break and therefore increased the wider economic and social issues has paid value and reach of tourism in the City region. -

4 4A Liverpool

Valid from 19 January 2020 Bus timetable Liverpool ONE- 4 4A Dingle/Sefton Park circulars These services are provided by Merseytravel LIVERPOOL CITY CENTRE Liverpool ONE Bus Station Kings Parade DINGLE Park Hill Road TOXTETH Croxteth Road (4) SEFTON PARK Greenbank Lane MOSSLEY HILL HOSPITAL Ullet Road DINGLE Park Hill Road Kings Parade LIVERPOOL CITY CENTRE Liverpool ONE Bus Station www.merseytravel.gov.uk What’s changed? Times are changed on Route 4. The 0900 Route 4 journey from Liverpool One Bus Station is rerouted and renumbered as route 4A, the times are subsequently changed. The Route 4A journey departing Liverpool One at 1500 is retimed along the route. All other 4A journeys remain unaltered. Any comments about this service? If you’ve got any comments or suggestions about the services shown in this timetable, please contact the bus company who runs the service: Peoplesbus Customer Service Centre, PO Box 57, Liverpool, Merseyside, L9 8YX 0151 523 4010 Contact us at Merseytravel: By e-mail [email protected] By phone 0151 330 1000 In writing PO Box 1976, Liverpool, L69 3HN Need some help or more information? For help planning your journey, call us between 0800 - 2000, 7 days a week on 0151 330 1000 You can visit one of our Travel Centres across the Merseytravel network to get information about all public transport services. To find out opening times, phone us on 0151 330 1000. Our website contains lots of information about public transport across Merseyside. You can visit our website at www.merseytravel.gov.uk Bus services may run to different timetables during bank and public holidays, so please check your travel plans in advance. -

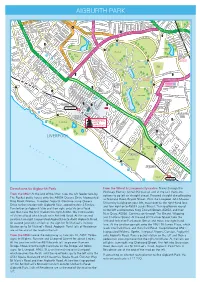

Aigburth Park

G R N G A A O A T D B N D LM G R R AIGBURTHA PARK 5 P R I R M B T 5 R LTAR E IN D D GR G 6 R 1 I Y CO O Superstore R R O 5 V Y 7 N D 2 R S E 5 E E L T A C L 4 A Toxteth Park R E 0 B E P A E D O Wavertree H S 7 A T A L S 8 Cemetery M N F R O Y T A Y E A S RM 1 R N Playground M R S P JE N D K V 9 G E L A IC R R K E D 5 OV N K R R O RW ST M L IN E O L A E O B O A O P 5 V O W IN A U C OL AD T R D A R D D O E A S S 6 P N U E Y R U B G U E E V D V W O TL G EN T 7 G D S EN A V M N N R D 1 7 I B UND A A N E 1 N L A 5 F R S V E B G G I N L L S E R D M A I T R O N I V V S R T W N A T A M K ST E E T V P V N A C Y K V L I V A T A D S R G K W I H A D H K A K H R T C N F I A R W IC ID I A P A H N N R N L L E A E R AV T D E N W S S L N ARDE D A T W D T N E A G K A Y GREENH H A H R E S D E B T B E M D T G E L M O R R Y O T V I N H O O O A D S S I T L M L R E T A W V O R K E T H W A T C P U S S R U Y P IT S T Y D C A N N R I O C H R C R R N X N R RL T E TE C N A DO T E E N TH M 9 A 56 G E C M O U 8 ND R S R R N 0 2 A S O 5 R B L E T T D R X A A L O R BE E S A R P M R Y T Y L A A C U T B D H H S M K RT ST S E T R O L E K I A H N L R W T T H D A L RD B B N I W A LA 5175 A U W I R T Y P S R R I F H EI S M S O Y C O L L T LA A O D O H A T T RD K R R H T O G D E N D L S S I R E DRI U V T Y R E H VE G D A ER E H N T ET A G L Y R EFTO XT R E V L H S I S N DR R H D E S G S O E T T W T H CR E S W A HR D R D Y T E N V O D U S A O M V B E N I O I IR R S N A RIDG N R B S A S N AL S T O T L D K S T R T S V T O R E T R E O A R EET E D TR K A D S LE T T E P E TI S N -

Liverpool Historic Settlement Study

Liverpool Historic Settlement Study Merseyside Historic Characterisation Project December 2011 Merseyside Historic Characterisation Project Museum of Liverpool Pier Head Liverpool L3 1DG © Trustees of National Museums Liverpool and English Heritage 2011 Contents Introduction to Historic Settlement Study..................................................................1 Aigburth....................................................................................................................4 Allerton.....................................................................................................................7 Anfield.................................................................................................................... 10 Broadgreen ............................................................................................................ 12 Childwall................................................................................................................. 14 Clubmoor ............................................................................................................... 16 Croxteth Park ......................................................................................................... 18 Dovecot.................................................................................................................. 20 Everton................................................................................................................... 22 Fairfield ................................................................................................................. -

LIVERPOOL, (COURT • Gibbon Wm

GIB LIVERPOOL, (COURT • GibBon Wm. H. Manor ho. Elm rd. Seafortb Given John Cecil M.D. Farloe, Elmsley road, Golding Alfred, 57 Litherland pk. Litherland GibBon Wm.R. 8 Amery gro. High. Tranmere,B Mossley hill Golding George, Chesterlie, .l'_renton road Gick John, 9 Caithness drive, Liscard Gjersiie Lorentz, 5 Brook road, W1ilton west, Higher Tranmere, B Giddings Miss, 6 Gardner road, Tue-Brook Gladding James, 128 Chatham street Golding George, Preston, Cheshire Gierson Richard M. 1615 Lodge la.Toxteth pk Gladstone Arthur Robertson J.P. Conrthey, Golding Miss, o Arundel avenue, Toxteth pk Gitford P. 4 Sonth Hill grove, Toxteth park Broad Green Golding Richard, 64 Falkner street 0 Gilbert Albert Edward, Lyndale, Woodend Gladstone Hugh Wm. o Meadowst.N.Brightn Golding T.V. Hesketh park, S~uthport park, Grassendale Gladstone Mrs. 21 Alton road, B Goldingay William, 9 Wright st. Egremont Gilbert Frank, The Allands, Liverpool road, Gladstone Richd. Fras. Courthey, Brorl.d Grn Gold,.;traw William, 27 Orrelllane, Walton Great Crll:'by Gladstone Robert, 21 Alton road, Oxton, B Goldsworth Wm.lll) MO!'cow dri.Stoneycroft Gilbert John, 35 Kremlin drive, Stonycroft GladstoneRbt. Woolton vale, Vale rd.Lit. Wltn Goldsworthy Capt.A.1 Rudgrave sq.Egremnt Gilbert John George, 26 Rawlins st. }<'airfield Gladstone Robertson, Norris green, Broad Goldsworthy George, 21 Lisc:ud gro. Liscard Gilbert Miss :M:ary E. 2 Walmer rd. Waterloo lane, West Derby Goldsworthy Thomas, 2 Baroda villas, Sea. GilbertMrs.1Eversley vls.Meadw st.NwBrghn Gladstone Thomas7 Chislehurst, Woodhey bank road, North Egremont Gilbert Mrs. J. A. 5 Higher par. New Brightn road, Bebington Goll Jn. -

How to Get to Liverpool Hope University

Issue 1 Spring 2012 The Merseyside Transport Partnership Transport Merseyside The D E This guide has been funded by the Department of Transport through the Local Sustainable Transport Fund. www.LetsTravelWise.org L P C A Y P C E E R R P R N I (Hope Park) (Hope N O T E D University Liverpool Hope Liverpool www.LetsTravelWise.org to learn more. more. learn to www.LetsTravelWise.org How to get to to get to How adult cycle skills and maintenance training sessions. Visit sessions. training maintenance and skills cycle adult details of organised rides and local bike shops and free and shops bike local and rides organised of details including route maps covering the whole of Merseyside, of whole the covering maps route including There are many opportunities to help cyclists on their way, their on cyclists help to opportunities many are There and lockers. lockers. and the locations of local train stations and cycle shelters shelters cycle and stations train local of locations the on the frequency of bus routes is displayed, along with with along displayed, is routes bus of frequency the on cycling options available at Hope Park campus. Information campus. Park Hope at available options cycling This guide shows all public transport and recommended and transport public all shows guide This you money. you journey a week helps to improve fitness and could save save could and fitness improve to helps week a journey Using public transport, walking or cycling for just one just for cycling or walking transport, public Using The campus is situated in a leafy suburb of Liverpool just four miles from the city centre, where traditional architecture sits beside contemporary buildings and facilities Liverpool Hope University wants to improve access to make it easier to travel to and from our campuses. -

Using Proximate Real Estate to Fund England's Nineteenth Century

Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes An International Quarterly ISSN: 1460-1176 (Print) 1943-2186 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tgah20 Using proximate real estate to fund England’s nineteenth century pioneering urban parks: viable vehicle or mendacious myth? John L. CromptonJOHN L. CROMPTON To cite this article: John L. CromptonJOHN L. CROMPTON (2019): Using proximate real estate to fund England’s nineteenth century pioneering urban parks: viable vehicle or mendacious myth?, Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes, DOI: 10.1080/14601176.2019.1638164 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14601176.2019.1638164 Published online: 25 Jul 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 23 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tgah20 Using proximate real estate to fund England’s nineteenth century pioneering urban parks: viable vehicle or mendacious myth? john l. crompton It could reasonably be posited that large public urban parks are one of Parliament which was a cumbersome and costly method.1 There were only England’s best ideas and one of its most widely adopted cultural exports. two alternatives. First, there were voluntary philanthropic subscription cam- They were first conceived, nurtured and implemented in England. From paigns that, for example, underwrote Victoria Park which opened in Bath in there they spread to the other UK countries, to the USA, to Commonwealth 1830; Queen’s Park, Philips Park and Peel Park in the Manchester area in the nations, and beyond. -

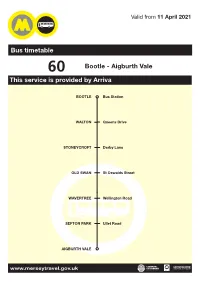

60 Bootle - Aigburth Vale This Service Is Provided by Arriva

Valid from 11 April 2021 Bus timetable 60 Bootle - Aigburth Vale This service is provided by Arriva BOOTLE Bus Station WALTON Queens Drive STONEYCROFT Derby Lane OLD SWAN St Oswalds Street WAVERTREE Wellington Road SEFTON PARK Ullet Road AIGBURTH VALE www.merseytravel.gov.uk What’s changed? From Bootle to Aigburth, Mondays-Fridays and Saturdays journeys have minor time changes. The last journey from Bootle Bus Station on Saturday is now half an hour later at 2315. Aigburth to Bootle service hasn’t changed. Any comments about this service? If you’ve got any comments or suggestions about the services shown in this timetable, please contact the bus company who runs the service: Arriva North West 73 Ormskirk Road, Aintree, Liverpool, L9 5AE 0344 800 44 11 or contact us at Merseytravel: By e-mail [email protected] By phone 0151 330 1000 In writing PO Box 1976, Liverpool, L69 3HN Need some help or more information? For help planning your journey, call 0151 330 1000, open 0800-2000, 7 days a week. You can visit one of our Travel Centres across the Merseytravel network to get information about all public transport services. To find out opening times, phone us on 0151 330 1000. Our website contains lots of information about public transport across Merseyside. You can visit our website at www.merseytravel.gov.uk Bus services may run to different timetables during bank and public holidays, so please check your travel plans in advance. Large print timetables We can supply this timetable in another format, such as large print. -

The Stoke Poges Society 2020

2020 Membership Application Programme of Events 2020 (Cont.) * Saturday Windsor & Eton Discover how beer is made - 18 July Brewery Tour one of Britain’s oldest Membership fee is only £8.00 traditions 16:00 Self Drive per annum. This entitles you to attendance at all Society events. Saturday Stoke Poges, Visit our stand at the 127th 25 July Wexham & Annual Show in the grounds Valuing our past… for the future 12:30 Fulmer of the Stoke Poges School, Horticultural Rogers Lane Non-members are welcome to Society The Stoke Poges Society attend an event for a fee of £2.00 Tuesday Prop House Trip Down Memory Lane 18 August Café, unless otherwise stated. Tell your story of village 14:00– 16:00 Pinewood memories The aim of the Society is the Nurseries SL3 6NB Open to all preservation and study of all matters Please make your cheque payable relating to the history and * Tuesday Members Only Private Tour of this development of Stoke Poges; to to: “The Stoke Poges Society” and 8 September Stoke Park sumptuous Hotel followed by refreshments collate and preserve archive material 13:30 Visit complete the form overleaf and and artefacts, and to make it return to: * Thursday The Annual Stoke Park Dinner available for members and other 15 October Stoke Poges Our Guest of Honour is The Society Dinner Countess Howe SSStJ DL interested parties. 19:00 3 course dinner with a glass Jane Wall of wine followed by tea/coffee www.bucksinfo.net/ TSPS Membership Secretary Tuesday stoke-poges-society 24 November St Andrews Talk on 143 Vine Road Youth Hall Fulmer Research