Using Proximate Real Estate to Fund England's Nineteenth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flaybrick Cemetery CMP Volume2 17Dec18.Pdf

FLAYBRICK MEMORIAL GARDENS CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN VOLUME TWO: ANALYSIS DECEMBER 2018 Eleanor Cooper On behalf of Purcell ® 29 Marygate, York YO30 7WH [email protected] www.purcelluk.com All rights in this work are reserved. No part of this work may be Issue 01 reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by any means March 2017 (including without limitation by photocopying or placing on a Wirral Borough Council website) without the prior permission in writing of Purcell except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Issue 02 Patents Act 1988. Applications for permission to reproduce any part August 2017 of this work should be addressed to Purcell at [email protected]. Wirral Borough Council Undertaking any unauthorised act in relation to this work may Issue 03 result in a civil claim for damages and/or criminal prosecution. October 2017 Any materials used in this work which are subject to third party Wirral Borough Council copyright have been reproduced under licence from the copyright owner except in the case of works of unknown authorship as Issue 04 defined by the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Any January 2018 person wishing to assert rights in relation to works which have Wirral Borough Council been reproduced as works of unknown authorship should contact Purcell at [email protected]. Issue 05 March 2018 Purcell asserts its moral rights to be identified as the author of Wirral Borough Council this work under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Consultation Draft Purcell® is the trading name of Purcell Miller Tritton LLP. -

Coach Welcome Scheme

Coach welcome scheme LIVERPOOL COACH WELCOME There is secure coach parking at the Eco Coach groups can register for a special Visitor Centre alongside the park and ride Coach Welcome, which involves a personal scheme. This includes lounge, kitchen welcome to the city of Liverpool from one and shower facilities for drivers. of our enthusiastic coach hosts, the latest For more information visit www.visitsouthport.com information on what’s on, complimentary or contact Steve Christian on +44 (0)151 934 2319 maps, rest room and refreshment facilities. For drivers, there are coach drop-off WIRRAL COACH WELCOME and pick-up facilities, parking and traffic For a Mersey Ferries river cruise, park at information and refreshments. Woodside Ferry Terminal. Mersey Ferries links There are two locations: Liverpool Cathedral a number of exciting waterfront attractions in the city’s historic Hope Street Quarter, in Liverpool and Wirral, enabling you to and at Liverpool ONE bus station. create flexible days out for your group. We recommend booking at least 10 days in advance. Port Sunlight, a fascinating 19th century garden • LIVERPOOL CATHEDRAL village, is a very popular group travel destination +44 (0)151 702 7284 and home to both the Port Sunlight Museum and [email protected] Lady Lever Art Gallery. There is extensive free coach parking adjacent to the Lady Lever Art Gallery, with • LIVERPOOL ONE BUS STATION the village attractions easily accessible on foot. +44 (0)151 330 1354 [email protected] For more information about these and more visit www.visitwirral.com/visitor-info/group-travel SOUTHPORT COACH WELCOME Coach hosts are available from April to October to meet and greet coach visitors disembarking at the coach drop-off point on Lord Street, adjacent to The Atkinson. -

Student Guide to Living in Liverpool

A STUDENT GUIDE TO LIVING IN LIVERPOOL www.hope.ac.uk 1 LIVERPOOL HOPE UNIVERSITY A STUDENT GUIDE TO LIVING IN LIVERPOOL CONTENTS THIS IS LIVERPOOL ........................................................ 4 LOCATION ....................................................................... 6 IN THE CITY .................................................................... 9 LIVERPOOL IN NUMBERS .............................................. 10 DID YOU KNOW? ............................................................. 11 OUR STUDENTS ............................................................. 12 HOW TO LIVE IN LIVERPOOL ......................................... 14 CULTURE ....................................................................... 17 FREE STUFF TO DO ........................................................ 20 FUN STUFF TO DO ......................................................... 23 NIGHTLIFE ..................................................................... 26 INDEPENDENT LIVERPOOL ......................................... 29 PLACES TO EAT .............................................................. 35 MUSIC IN LIVERPOOL .................................................... 40 PLACES TO SHOP ........................................................... 45 SPORT IN LIVERPOOL .................................................... 50 “LIFE GOES ON SPORT AT HOPE ............................................................. 52 DAY AFTER DAY...” LIVING ON CAMPUS ....................................................... 55 CONTACT -

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Introduction • 1 Rana Chhina Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World i Capt Suresh Sharma Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Rana T.S. Chhina Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India 2014 First published 2014 © United Service Institution of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author / publisher. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3 Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India Rao Tula Ram Marg, Post Bag No. 8, Vasant Vihar PO New Delhi 110057, India. email: [email protected] www.usiofindia.org Printed by Aegean Offset Printers, Gr. Noida, India. Capt Suresh Sharma Contents Foreword ix Introduction 1 Section I The Two World Wars 15 Memorials around the World 47 Section II The Wars since Independence 129 Memorials in India 161 Acknowledgements 206 Appendix A Indian War Dead WW-I & II: Details by CWGC Memorial 208 Appendix B CWGC Commitment Summary by Country 230 The Gift of India Is there ought you need that my hands hold? Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and the West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, and yielded the sons of my stricken womb to the drum-beats of duty, the sabers of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, they lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance on the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France. -

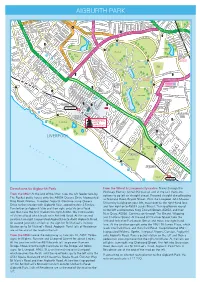

Aigburth Park

G R N G A A O A T D B N D LM G R R AIGBURTHA PARK 5 P R I R M B T 5 R LTAR E IN D D GR G 6 R 1 I Y CO O Superstore R R O 5 V Y 7 N D 2 R S E 5 E E L T A C L 4 A Toxteth Park R E 0 B E P A E D O Wavertree H S 7 A T A L S 8 Cemetery M N F R O Y T A Y E A S RM 1 R N Playground M R S P JE N D K V 9 G E L A IC R R K E D 5 OV N K R R O RW ST M L IN E O L A E O B O A O P 5 V O W IN A U C OL AD T R D A R D D O E A S S 6 P N U E Y R U B G U E E V D V W O TL G EN T 7 G D S EN A V M N N R D 1 7 I B UND A A N E 1 N L A 5 F R S V E B G G I N L L S E R D M A I T R O N I V V S R T W N A T A M K ST E E T V P V N A C Y K V L I V A T A D S R G K W I H A D H K A K H R T C N F I A R W IC ID I A P A H N N R N L L E A E R AV T D E N W S S L N ARDE D A T W D T N E A G K A Y GREENH H A H R E S D E B T B E M D T G E L M O R R Y O T V I N H O O O A D S S I T L M L R E T A W V O R K E T H W A T C P U S S R U Y P IT S T Y D C A N N R I O C H R C R R N X N R RL T E TE C N A DO T E E N TH M 9 A 56 G E C M O U 8 ND R S R R N 0 2 A S O 5 R B L E T T D R X A A L O R BE E S A R P M R Y T Y L A A C U T B D H H S M K RT ST S E T R O L E K I A H N L R W T T H D A L RD B B N I W A LA 5175 A U W I R T Y P S R R I F H EI S M S O Y C O L L T LA A O D O H A T T RD K R R H T O G D E N D L S S I R E DRI U V T Y R E H VE G D A ER E H N T ET A G L Y R EFTO XT R E V L H S I S N DR R H D E S G S O E T T W T H CR E S W A HR D R D Y T E N V O D U S A O M V B E N I O I IR R S N A RIDG N R B S A S N AL S T O T L D K S T R T S V T O R E T R E O A R EET E D TR K A D S LE T T E P E TI S N -

Liverpool Historic Settlement Study

Liverpool Historic Settlement Study Merseyside Historic Characterisation Project December 2011 Merseyside Historic Characterisation Project Museum of Liverpool Pier Head Liverpool L3 1DG © Trustees of National Museums Liverpool and English Heritage 2011 Contents Introduction to Historic Settlement Study..................................................................1 Aigburth....................................................................................................................4 Allerton.....................................................................................................................7 Anfield.................................................................................................................... 10 Broadgreen ............................................................................................................ 12 Childwall................................................................................................................. 14 Clubmoor ............................................................................................................... 16 Croxteth Park ......................................................................................................... 18 Dovecot.................................................................................................................. 20 Everton................................................................................................................... 22 Fairfield ................................................................................................................. -

Audley Family AA

This document has been produced for display on www.audleyfamilyhistory.com & www.audley.one-name.net Please feel free to distribute this document to others but please give credit to the website. This document should not be used for commercial gain Audley Family History Compiled for www.audleyfamilyhistory.com & www.audley.one-name.net Family AA Audley of Liverpool The Descendants of {AA2} Samuel Audley (the son of {A1} John Audley) who married Hannah Gerrard in 1799 Table of Contents REVISION..........................................................................................................................................................................2 SPARE TAG NUMBERS..................................................................................................................................................2 INTRODUCTION..............................................................................................................................................................2 SIMPLE FAMILY TREE (RELATIONSHIP TO OTHER AUDLEY FAMILIES)...................................................2 SIMPLE FAMILY TREE (FOR THE PARENTAGE OF {AA2} SAMUEL AUDLEY SEE THE AUDLEY FAMILY ‘A’ NARRATIVE.)...............................................................................................................................................................3 DETAILED FAMILY TREE..........................................................................................................................................12 SUPPORTING EVIDENCE............................................................................................................................................39 -

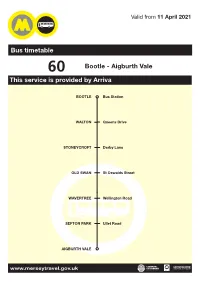

60 Bootle - Aigburth Vale This Service Is Provided by Arriva

Valid from 11 April 2021 Bus timetable 60 Bootle - Aigburth Vale This service is provided by Arriva BOOTLE Bus Station WALTON Queens Drive STONEYCROFT Derby Lane OLD SWAN St Oswalds Street WAVERTREE Wellington Road SEFTON PARK Ullet Road AIGBURTH VALE www.merseytravel.gov.uk What’s changed? From Bootle to Aigburth, Mondays-Fridays and Saturdays journeys have minor time changes. The last journey from Bootle Bus Station on Saturday is now half an hour later at 2315. Aigburth to Bootle service hasn’t changed. Any comments about this service? If you’ve got any comments or suggestions about the services shown in this timetable, please contact the bus company who runs the service: Arriva North West 73 Ormskirk Road, Aintree, Liverpool, L9 5AE 0344 800 44 11 or contact us at Merseytravel: By e-mail [email protected] By phone 0151 330 1000 In writing PO Box 1976, Liverpool, L69 3HN Need some help or more information? For help planning your journey, call 0151 330 1000, open 0800-2000, 7 days a week. You can visit one of our Travel Centres across the Merseytravel network to get information about all public transport services. To find out opening times, phone us on 0151 330 1000. Our website contains lots of information about public transport across Merseyside. You can visit our website at www.merseytravel.gov.uk Bus services may run to different timetables during bank and public holidays, so please check your travel plans in advance. Large print timetables We can supply this timetable in another format, such as large print. -

Casualties of the AUXILIARY TERRITORIAL SERVICE

Casualties of the AUXILIARY TERRITORIAL SERVICE From the Database of The Commonwealth War Graves Commission Casualties of the AUXILIARY TERRITORIAL SERVICE. From the Database of The Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Austria KLAGENFURT WAR CEMETERY Commonwealth War Dead 1939-1945 DIXON, Lance Corporal, RUBY EDITH, W/242531. Auxiliary Territorial Service. 4th October 1945. Age 22. Daughter of James and Edith Annie Dixon, of Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire. 6. A. 6. TOLMIE, Subaltern, CATHERINE, W/338420. Auxiliary Territorial Service. 14th November 1947. Age 32. Daughter of Alexander and Mary Tolmie, of Drumnadrochit, Inverness-shire. 8. C. 10. Belgium BRUGGE GENERAL CEMETERY - Brugge, West-Vlaanderen Commonwealth War Dead 1939-1945 MATHER, Lance Serjeant, DORIS, W/39228. Auxiliary Territorial Service attd. Royal Corps of Sig- nals. 24th August 1945. Age 23. Daughter of George L. and Edith Mather, of Hull. Plot 63. Row 5. Grave 1 3. BRUSSELS TOWN CEMETERY - Evere, Vlaams-Brabant Commonwealth War Dead 1939-1945 EASTON, Private, ELIZABETH PEARSON, W/49689. 1st Continental Group. Auxiliary Territorial Ser- vice. 25th December 1944. Age 22. X. 27. 19. MORGAN, Private, ELSIE, W/264085. 2nd Continental Group. Auxiliary Territorial Service. 30th Au- gust 1945. Age 26. Daughter of Alfred Henry and Jane Midgley Morgan, of Newcastle-on-Tyne. X. 32. 14. SMITH, Private, BEATRICE MARY, W/225214. 'E' Coy., 1st Continental Group. Auxiliary Territorial Service. 14th November 1944. Age 25. X. 26. 12. GENT CITY CEMETERY - Gent, Oost-Vlaanderen Commonwealth War Dead 1939-1945 FELLOWS, Private, DORIS MARY, W/76624. Auxiliary Territorial Service attd. 137 H.A.A. Regt. Royal Artillery. 23rd May 1945. Age 21. -

The Stoke Poges Society 2020

2020 Membership Application Programme of Events 2020 (Cont.) * Saturday Windsor & Eton Discover how beer is made - 18 July Brewery Tour one of Britain’s oldest Membership fee is only £8.00 traditions 16:00 Self Drive per annum. This entitles you to attendance at all Society events. Saturday Stoke Poges, Visit our stand at the 127th 25 July Wexham & Annual Show in the grounds Valuing our past… for the future 12:30 Fulmer of the Stoke Poges School, Horticultural Rogers Lane Non-members are welcome to Society The Stoke Poges Society attend an event for a fee of £2.00 Tuesday Prop House Trip Down Memory Lane 18 August Café, unless otherwise stated. Tell your story of village 14:00– 16:00 Pinewood memories The aim of the Society is the Nurseries SL3 6NB Open to all preservation and study of all matters Please make your cheque payable relating to the history and * Tuesday Members Only Private Tour of this development of Stoke Poges; to to: “The Stoke Poges Society” and 8 September Stoke Park sumptuous Hotel followed by refreshments collate and preserve archive material 13:30 Visit complete the form overleaf and and artefacts, and to make it return to: * Thursday The Annual Stoke Park Dinner available for members and other 15 October Stoke Poges Our Guest of Honour is The Society Dinner Countess Howe SSStJ DL interested parties. 19:00 3 course dinner with a glass Jane Wall of wine followed by tea/coffee www.bucksinfo.net/ TSPS Membership Secretary Tuesday stoke-poges-society 24 November St Andrews Talk on 143 Vine Road Youth Hall Fulmer Research -

Liverpool History Society Newsletter No 14, Winter 2005-6

Liverpool History Society Newsletter No 14, Winter 2005-6 Newsletter No 14 Winter 2005-06 Reg Charity HISTORY SOCIETY NoNo 1093736 1093736 Editorial Although editorial material in this Newsletter is usually anonymous, an exception is made now because what follows are my thoughts alone, and not necessarily those of other members of the LHS Committee. During October, I attended a conference on “Liverpool and Transatlantic Slavery, organised by the Historic Society of Lancashire & Cheshire and National Museums Liverpool. One friend, when asked whether he would be attending, said he would not because he was a bit fed up with Liverpool continually beating its breast about the Slave Trade. A little while later, while reading the story of a fugitive slave from Maryland who fled to Liverpool in 1850 to escape America’s Fugitive Slave Law and was less than well received, an- other friend asked me whether Liverpool was really that bad?” These two comments seem to express two ex- tremes of attitude towards what is, inescapably, a fundamental part of Liverpool’s history and past prosper- ity - its involvement in the Slave Trade itself, and with goods produced by the victims of that trade & their descendants. At another conference, this time on “Poverty and Experience”, held at Edge Hill College and again organised by the HSLC, two of the speakers very vividly described the poverty experienced by some Liverpool families in years gone by. Although an obvious one, I have not been able to escape the thought of just how deeply these experiences of deprivation must have etched themselves, on the minds, not only of those who went through them, but also on those of their descendants, ‘even unto the third and fourth generation’, not least be- cause of how for both slaves and poor, prosperity and conspicuous consumption were so evident not very far away. -

Raaf Personnel Serving on Attachment in Royal Air Force Squadrons and Support Units

Cover Design by: 121Creative Lower Ground Floor, Ethos House, 28-36 Ainslie Pl, Canberra ACT 2601 phone. (02) 6243 6012 email. [email protected] www.121creative.com.au Printed by: Kwik Kopy Canberra Lower Ground Floor, Ethos House, 28-36 Ainslie Pl, Canberra ACT 2601 phone. (02) 6243 6066 email. [email protected] www.canberra.kwikkopy.com.au Compilation Alan Storr 2006 The information appearing in this compilation is derived from the collections of the Australian War Memorial and the National Archives of Australia. Author : Alan Storr Alan was born in Melbourne Australia in 1921. He joined the RAAF in October 1941 and served in the Pacific theatre of war. He was an Observer and did a tour of operations with No 7 Squadron RAAF (Beauforts), and later was Flight Navigation Officer of No 201 Flight RAAF (Liberators). He was discharged Flight Lieutenant in February 1946. He has spent most of his Public Service working life in Canberra – first arriving in the National Capital in 1938. He held senior positions in the Department of Air (First Assistant Secretary) and the Department of Defence (Senior Assistant Secretary), and retired from the public service in 1975. He holds a Bachelor of Commerce degree (Melbourne University) and was a graduate of the Australian Staff College, ‘Manyung’, Mt Eliza, Victoria. He has been a volunteer at the Australian War Memorial for 21 years doing research into aircraft relics held at the AWM, and more recently research work into RAAF World War 2 fatalities. He has written and published eight books on RAAF fatalities in the eight RAAF Squadrons serving in RAF Bomber Command in WW2.