Footprint {Compendium}

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shines Bright at SCA Östrand 24

ENGLISH Magazine of Pulp & Paper // No. 38 / 2-2018 Södra Cell – IDEAS ANDRITZ & Zero Fossile Fuels // 34 Digital Twin // 48 Novimpianti // 56 HELIOS shines bright at SCA Östrand 24 New member of the ANDRITZ GROUP: Xerium Technologies, Inc. CONTENTS HELIOS SHINES BRIGHT 05 Management Message 44 We Need to Protect ... // UPM Schongau AT SCA ÖSTRAND 06 News 48 IDEAS Digital Twin // TechNews 08 Taking Control // Henan Tianbang 52 Small Steps ... // Braviken Mill Cover Story // 24 14 Cutting Edge // CETI 54 Pulp Trends // Market Trend 18 Fiber GPS™ // Performance Boosters 56 Mutual Respect // ANDRITZ & Novimpianti 22 New Innovation EvoDry™ // Key Equipment 61 Technology Outlook // ANDRITZ Automation 24 SCA Östrand // Helios 62 Orders & Start-ups 34 Zero Fossile Fuels // Södra Cell Mörrum 64 Did You Know That … 38 A Day in the Life of ... // Ilkka Poikolainen AUGMENTED REALITY CONTENT To view videos, illustrations and picture galleries in a more direct and lively way, we added augmented reality to several articles! Download our ANDRITZ AR APP on our website or in the AppStore/PlayStore! SCAN THE MARKED PAGES AND EXPERIENCE THE ENHANCED CONTENT. 08 14 Engineered Success – Vision becoming reality The common thread of “Engineered Success” runs throughout this issue of the SPECTRUM magazine. First of all, we are delighted to bring you coverage of some major recent projects ANDRITZ has been involved in, for instance SCA Östrand’s “Helios”, our cover story, has seen the doubling of capacity of its softwood kraft pulp mill in Sundsvall, northern Sweden. As well, the delivery and installation of the new evaporation plant at Södra Cell’s Mörrum mill, Sweden, which is assisting the Södra group in its ambitious sustainability targets. -

Paper, Paperboard and Wood Pulp Markets, 2010-2011 Chapter 8

UNECE/FAO Forest Products Annual Market Review, 2010-2011 __________________________________________________________ 71 8 Paper, paperboard and woodpulp markets, 2010-2011 Lead Author, Peter Ince Contributing Authors, Eduard Akim, Bernard Lombard, Tomas Parik and Anastasia Tolmatsova Highlights • Paper and paperboard output rebounded along with overall industrial production in both Europe and the United States, but has not yet fully recovered to the peak levels of 2007-2008. • Generally more robust market conditions prevailed from 2010 to early 2011, with higher consumption and prices for most pulp, paper and paperboard commodities. • Prices reached a plateau by late 2010 and may have peaked in a cycle that began with rebound from the global financial crisis of 2008-2009; but prices still remained high in early 2011. • The Russian Federation is seeing an almost complete recovery of pulp and paper output to the levels that preceded the global financial crisis of 2008-2009. • European pulp, paper and paperboard output rebounded in 2010 after declining in 2008-2009, but the production levels before the crisis have not yet been reached. • Similarly, US production of pulp, paper and paperboard all rebounded from the sharp declines of 2008-2009, but production levels in 2010-2011 remained below previous cyclical peak levels. • A major project to expand use of larch was initiated in the Russian Federation, while wood pellet output and wood energy use also expanded in the Russian pulp and paper industry. • The market rebound coincides with expanding industry interest in the contributions of paper and paperboard products to green and sustainable development. • Green and sustainable product features such as use of renewable resources and product recyclability help support sustainability initiatives and an evolving symbiotic relationship between pulp and paper market development and the green economy. -

Holmen Paper Magazine Study

THE FUTURE OF MAGAZINES MARKET STUDY BY HOLMEN PAPER With the past decades’ rapid digital evolution, print media in almost all forms has taken a step back. As a company selling printing paper, Holmen Paper has observed and experienced this decline first hand. Newspapers was the first segment that suffered a rapid decrease in readers and is, as a result, no longer the largest end-use segment for graphical paper. Instead magazines now hold that position. Hence the future of the magazine market is crucial to the future of graphical paper. This is why we decided to conduct this study, where we look at how publishers meet the new challenges, how pricing is affected and how the readers demands are changing. TABLE OF CONTENTS MARKET SELLING PRICE 3 OVERVIEW 13 VS ADVERTISING How is the magazine market developing? What sets the price of a magazine? SHIFT IN MILLENNIALS’ BUSINESS READING 7 MODELS 16 HABITS Are the publishers’ changes radical enough? What does this group want in a printed magazine? Understanding where the magazine market is heading, helps you to gain insights and make sound future business decisions. This study therefore starts by looking at the current state of the magazine market, including historic developments as well as forecasted development. It then proceeds to look at the market from a publisher’s perspective, based on qualitative interviews with European publishers. The outcome is an extensive summary of the challenges that many publishers are experiencing, but also how they adapt their business models to to overcome them. The study also includes a thorough analysis of a large number of consumer magazines, where attributes such as price versus advertising density are investigated. -

Magazine Recycling May Boom As New Technology Increases

Magazine Recycling May Boom as New Technology Increases Magazine publishers have long been locked in editorial and financial competition with their media brethren - newspapers. But in at least one respect, the competi- tion hasn’t even been close. While environmentalists and state legislatures have been successfulty exerting pres- sure on newspapers to print ever-more copies on recyc- led paper, the magazine in- dustry has largely escaped unscathed. That seem to be about to change. While newspaper publish- ers have been under regula- tory and consumer pressure for several years to concen- trate their attention on re- cycling efforts, their maga- stock into paper. zine counterparts are only newsprint become available. There is a great deal of beginning to feel the heat, Flotation technology, still interest,” said Rod Edwards, since until only recently has being developed in the U.S., is vice president of the Ameri- it been feasible to recycle now in use in only a handful can Paper Institute’s paper- most glossy magazine of mills around the country. board group. “Magazine stock back into reuse. That number is headed for a publishers, distributors and FUTURE DEMAND. The mar- steep incline, and soon. wholesalers are all being ket for recycled magazine The flotation system is a asked leading questions on stock has existed for years, deinking system that has where they stand on recycl- but it has been limited to been used for a long time ing ethics. And this, in my uses in the paperboard in- in Europe and Japan. It is a opinion, comes up faster dustry, which has employed substitute for the long-stand- and faster to the surface recycled magazine paper in ing washing procedure used since Earth Day.” producing boxes and home- by U.S. -

Evaluation & Improvement of Surface Properties of Newsprint

G C C EVALUATION & IMPROVEMENT OF SURFACE PROPERTIES OF NEWSPRINT ,,- MANUFACTURED FROM RECYCLED c FIBERS (CESS PROJECT) L (. C <, ( L \. f \ , ( CENTRAL PULP & PAPER RESEARCH INSTITUTE SAHARANPUR - 247001 (U.P.) EVALUATION & IMPROVEMENT OF SURFACE PROPERTIES OF NEWSPRINT MANUFACTURED FROM RECYCLED FIBERS (CESS PROJECT) Based on the work of Dr. Y. V. Sood, P.C. Pande Sanjay Tyagi, R. Neethikumar, Arti Pandey, Nisha, Indranil Payra, Renu Tyagi, T. Johri, & Shobit Marwah CENTRAL PULP & PAPER RESEARCH INSTITUTE SAHARANPUR - 247001 (U.P.) ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The authors are thankful to Dr. T. K. Roy, Officiating Director, Central Pulp & Paper Research Institute for useful technical discussions during the preparation of the final report. The management of Central Pulp & Paper Research Institute is thankful to the management of MIs Rolex Paper Mills Ltd., MIs Ajanta Paper Mills Ltd., MIs Sri Ramdas Paper Boards Pvt Ltd., MIs Sreen Sri Papers Ltd., MIs Nelsun Paper Mills Ltd., MIs Cosboard Industries Ltd., MIs Shakumbhari Straw Products Ltd., MIs Pragati Papers Ltd. & MIs Delta Paper Mills Ltd. for their cooperation during the course of the investigation of this project. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Due to lack of suitable fibrous raw material, India for the last few decades -has been importing about 50% (±10 %) of its requirement of newsprint. The scenario is slowly changing as the recycling of waste paper is gaining momentum and this substantially improve the production of indigenous newsprint and reduce the imports in near future~At present, a large number of small and medium paper mills based on waste paper are manufacturing newsprint. Only few of these mills are able to meet the minimum quality standard. -

This Is Norske Skog in Words and Numbers

This is Norske Skog in words and numbers. Norske Skog is a leading Norwegian industrial company which focu- ses on these core areas: printing paper for newspapers and maga- zines, bleached sulphate pulp, and wood-based building materials. The Group has about 5,800 employees, and its operating income in 1996 was NOK 13,265 million. 78% of its income came from export markets, primarily in Europe, but also in the US and the Far East. The Group operates 23 companies in Norway, one mill in Austria and one in France. Its activities are organized in fourAreas: Paper, Fibre, Building Materials and Resources. In printing paper, Norske Skog is one of the world's leading suppliers, with capacity of 2.3 million tonnes in a market that totals about 50 million tonnes. Norske Skog is the third largest manufactu- rer of printing paper in Europe, and the world's fifth largest news- print producer. The pulp sold by the Group is used in the production of printing paper, fine paper and tissue. Norske Skog Bygg AS is Norway's largest producer of building materials: sawn timber for building purposes, board for the building and furniture industries, and flooring products. Since its foundation in 1962, Norske Skog has grown rapidly through mergers with other companies, and major investments in new mills, both in Norway and abroad. Since 1990 the Group has in- creased its printing paper capacity by one million tonnes, or just over 70%. Norske Skog has a sound financial basis, with total assets of NOK 16,623 million, and an equity capital ratio of 45,9%. -

Introduction to Stock Prep Refining Introduction to Stock Prep Refining 2016 Edition

Introduction to Stock Prep Refining Introduction to Stock Prep Refining 2016 Edition Table of Contents Page 1. Introduction . 3 2. Trees, Wood and Fiber . 4 3. Pulping for Paper & Paperboard Manufacturing . 8 4. Structure of Paper & Role of Refining . 11 5. Pulp Quality Measurements . 14 6. Paper Quality Measurements . 17 7. Theory of Refining: i) Qualitative Analysis . 20 ii) Quantitative Analysis . 23 8. Refiner Plate Selection: i) Correct Amount of Refining (Specific Energy Input) . 25 ii) Correct Intensity of Refining (Specific Edge Load) . 27 9. Flow Considerations in a Stock Preparation Refiner . 30 10. Conclusion . 31 Appendix A – No load power in a stock prep refiner . 32 Appendix B – Flow considerations in a stock prep refiner . 34 Appendix C – Case study and sample calculations . 40 2 1. Introduction The purpose of this manual is to present an easy to understand description of the stock preparation refin- ing process. Useful methods for analyzing the process will be presented, together with guidelines for the proper selection of refiner fillings and operation of refiners. It is difficult to learn about pulp refining without first knowing something about the overall process of papermaking. This introductory manual will provide a very brief discussion of the process of converting trees into finished paper products. To include such a broad scope of information requires a certain degree of simplification. Nevertheless, the big picture is very helpful when considering pulp refining applications, identifying process problems and recognizing the real economic opportunities of an optimized system. The refining technologist must learn how to select refiner fillings and operate refiners so as to optimize the performance of the paper being produced using available raw materials. -

Press Release

Press release 19 November 2014 New product reduces newsprint capacity Holmen Paper is launching a new product in the SC segment in spring 2015, which will reduce the company’s production of newsprint. “This new initiative will quickly bring about a significant change in newsprint volumes,” comments sales and marketing director Karolina Svensson. Intensive preparations are under way on PM 53 at Braviken Paper Mill outside Norrköping, Sweden, for the conversion work that is scheduled to begin at the end of January next year. PM 53 is Braviken’s largest machine, with an annual capacity of 310 000 tonnes for the current product mix. The machine produces Holmen NEWS (newsprint) and Holmen XLNT – the uncoated magazine paper that makes up Holmen Paper’s single biggest product family. It is the production of newsprint for export outside the Nordic region that is going to be reduced when the new product is introduced next year. “We are predicting a rapid rise in volumes for the new product,” says Karolina Svensson. “The aim is to achieve an annualised running rate for production and sales of more than 100 000 tonnes by the end of 2015. “We’ll be reducing the production of newsprint at a corresponding rate, and in the longer term we’ll only keep the volumes to supply our local markets in Scandinavia.” Holmen Paper judges that its own measures, combined with previously announced capacity closures elsewhere in the market, will considerably improve capacity utilisation for newsprint in 2015. For more information, please contact: Jonas Lindell, Communications Manager, tel. +46 (0)70-323 20 13 E-mail [email protected] This is information that Holmen AB is obliged to disclose under the Swedish Securities Market Act and the Swedish Financial Instruments Trading Act. -

Forest Paperboard Paper Wood Products Renewable Energy the Year in Brief 3 Holmen in Brief CEO’S Message 4

Forest Paperboard Paper Wood Products Renewable Energy The year in brief 3 Holmen in brief CEO’s message 4 Strategy and targets 6 Forest 10 Paperboard 12 Paper 14 Forest Wood Products 16 Active and sustainable forestry is Renewable Energy 18 conducted on over a million hectares A sustainable business 20 of productive forest land owned by Holmen. The annual harvest amounts Environment 22 to 3 million cubic metres. Employees 24 UN Sustainable Development Goals 26 Corporate governance report 28 Paperboard Risk management 32 Paperboard in the premium consumer Shareholder information 36 packaging segment. Production, which takes place at one Swedish Financial statements 38 and one UK mill, amounts to 0.5 million tonnes a year. Notes 44 Proposed appropriation of profits 66 Auditor’s report 67 Review of Sustainability Report 69 Paper Board of Directors 70 Paper for magazines, books and Group management 72 advertising. The two Swedish mills produce a combined total Key figures 73 of 1 million tonnes per year. Ten-year review, finance 74 Five-year review, sustainability 76 Definitions, glossary and references 78 Wood Products Calendar 79 Wood products for the joinery and construction industries. The annual production at three The Board of Directors and the CEO of Holmen Aktiebolag (publ.), corporate sawmills amounts to just under identity number 556001-3301, submit their annual report for the parent 1 million cubic metres. The company and the Group for the 2018 financial year. The annual report com- prises the administration report (pages 2–3, 8–9, 23–24, 28–37, 66, 70–71) by-products are used in the and the financial statements, together with the notes and supplementary Group’s paperboard and information (pages 38–65). -

Holmen's Year-End Report 2014

Holmen’s year-end report 2014 Quarter Full year SEKm 4-14 3-14 4-13 2014 2013 Net turnover 4 011 3 956 3 938 15 994 16 231 Operating profit excl. items affecting comparability 472 522 338 1 734 1 209 Operating profit 22 522 338 1 284 1 069 Profit after tax -4 385 230 907 711 Earnings per share, SEK -0.1 4.6 2.7 10.8 8.5 Return on equity, % 0.0 7.4 4.5 4.3 3.4 Cash flow before investing activities 414 738 444 2 176 2 011 Debt/equity ratio 0.28 0.29 0.29 0.28 0.29 . Operating profit, excluding items affecting comparability, for 2014 was SEK 1 734 million (2013: 1 209). The improvement in profit is due to higher prices for printing paper and sawn timber, a weaker Swedish krona and reduced production costs for paperboard. Operating profit for the fourth quarter, excluding items affecting comparability, amounted to SEK 472 million, which was SEK 50 million lower than in the third quarter owing mainly to seasonally higher staff and energy costs. Operating profit for 2014 after items affecting comparability amounted to SEK 1 284 million (1 069). In the fourth quarter, an impairment of SEK 450 million was recorded for Braviken Sawmill, which is reported as an item affecting comparability. Profit after tax amounted to SEK 907 million (711), which corresponds to earnings per share of SEK 10.8 (8.5). Excluding items affecting comparability, profit after tax amounted to SEK 1 258 million (820) and earnings per share was SEK 15.0 (9.8). -

Forest and Paper Industry

FOREST AND PAPER INDUSTRY A mature industry that has done much to clean up its act. http://individual.utoronto.ca/abdel_rahman/paper/fpmp.html What are the primary environmental issues concerning the forest and paper industry? 1. Sustainability of forest resources: trees + habitats + species + water 2. Clean paper making: transportation to and from paper mill energy consumption water usage bleaching and other chemicals 3. Paper consumption: Can it be reduced? 4. Recycling of used paper and cardboard energy, chemicals recycling vs. incineration 5. Alternatives to wood for paper? Alternatives to paper itself? 1 www.automation.com/sitepages/pid1988.php Paper is a commodity: low design, near impossibility of changing the product itself huge amounts → huge impact nonetheless Paper accounts for 2.5% of industrial production 2.0% of world trade Paper consumption is related to population and to wealth 2 Source: Earth Trends, 2005 data So, we consume more paper than others. Why? Hint: Paper consumption is highly correlated with wealth. 3 For a wide range of countries Zoom on the less wealthy countries (bottom left of previous plot) 4 Look at historical data: GNP is about the only factor affecting paper consumption. Paper Task Force, © Force, Task Paper Fund defense Environmental 1995 5 Think of making useful by-products along the way. http://www.agenda2020.org/Tech/Biorefinery/IFPB_research.htm 6 1. Forest logging A tree = 25% branches and bark 75% trunk wood → logs Wood log = 27% lignin (glue) 73% fiber (what goes into paper) Every tree requires 130 gallons (490 L) of water for growth 50 gallons (189 L) of water for processing into paper The production of 1 metric ton of paper requires 17 trees (in average) 24 trees for white office paper, 12 trees for newsprint 25 m3 of water 10,061 kWh of electricity 680 gallons (2.57 m3) of oil 7 1 ton of uncoated virgin (non-recycled) printing and office paper uses 24 trees 1 ton of 100% virgin (non-recycled) newsprint uses 12 trees A "pallet" of copier paper (20-lb. -

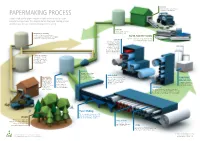

Papermaking PROCESS to Separate the Component Fibres

PULPING Paper for recycling is dissolved into pulp PAPERMAKING PROCESS to separate the component fibres. Today’s high quality papers require a highly technical and accurate manufacturing process. This diagram details the paper making process and illustrates the use of wood and paper for recycling. DE-INKING Adhesives and ink are removed MECHANICAL PULPING using a flotation process. Woodchips are ground to separate the fibres. Pulps are used to make high volume commodity printing PAPER FOR RECYCLING products such as newsprint and magazine paper. Paper for recycling is an important material COATING for the pulp and paper industry. In the coating process, coating color is spread onto the paper surface. The coating colour contains pigments, binding agents, and various additives. Coating the paper several times often improve its printing properties. High-grade printing paper is coated up to 3 times. CHEMICAL PULPING The woodchips are cooked to remove lignin. Burning of the process by-products enables the whole pulping process to be energy self-sufficient. HEADBOX The headbox squirts a mixture of water and fibre through a thin horizontal slit across the WIRE SECTION DE-BARKING machine’s width onto an endless The water is then removed on this FINISHING AND CHIPPING CLEANING moving wire mesh. wire section. Here the fibres starts Bark which cannot be The fibres are then washed; to spread and consolidate into a REELS AND SHEETS used for papermaking screened and dried. thin mat. This process is called The papers are then wound into is stripped from the a reel or cut into sheets, ready The pulp is ready to be “sheet formation”.