Special Feature the Crisis in Yemen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cholera Outbreak Weekly AWD/Cholera Situation Report 10 – 17 November 2016

YEMEN: Cholera Outbreak Weekly AWD/Cholera Situation Report 10 – 17 November 2016 This official joint-report is based on information Yemen Cholera Taskforce, which is led by the Ministry of Health, WHO/Health Cluster, UNICEF/WASH Cluster and is supported by OCHA. Key Figures As of 17 November 2016, 90 Al Jawf Aflah Ash Shawm Khamir Kuhlan Ash Sharaf Abs Amran cases of cholera were confirmed Hajjah Al Miftah Hadramaut Ash Shahil Az Zuhr Arhab Nihm A ah Sharas in 29 districts with 8 cases of lluh ey ah Bani Qa'is HamdanBani Al Harith Marib deaths from cholera. Amanat Al AsimahBani Hushaysh Al Mahwit Ma'ain Sana'a Az Zaydiyah As Sabain n Khwlan As Salif a h n a S WHO/ MoPHP estimates that Bajil As Salif ra Al Marawi'ah Bu Al Mina Shabwah 7.6M people are at risk in 15 Al HaliAl Hudaydah Al Hawak Al MansuriyahRaymah Ad Durayhimi Dhamar governorates. iah aq l F h t A a ay y B r Y a a r h im S Al Bayda bid Za h s A total of 4,825 suspected cases A Hazm Al Udayn HubayshAl Makhadir Ibb Ash Sha'ir ZabidJabal Ra's s Ibb Ba'dan ra Qa'atabah Al Bayda City ay Hays Al Udayn uk are reported in 64 districts. JiblahAl Mashannah M Far Al Udayn Al Dhale'e M Dhi As SufalAs Sayyani a Ash Shu'ayb Al Khawkhah h a As Sabrah s Ad Dhale'e q u Al Hussein b H Al Khawkhah a Jahaf n l Abyan a A Cholera case fatality rate (CFR) h Al Azariq a h k u Mawza M TaizzJabal Habashy l A is 1.5 % Al Milah Al Wazi'iyah Lahj T u Al Hawtah Tur A b Incidence rate is 4 cases per l Bah a a h n Dar Sad Khur Maksar Al Madaribah Wa Al Arah Aden Al Mansura 10,000. -

Saudi Reaction to Bab El Mandeb Attack Draws Attention to Iranian

UK £2 www.thearabweekly.com Issue 167, Year 4 July 29, 2018 EU €2.50 ISIS’s bloody The role of the Sheikh resilience in Zayed Grand Mosque Syria and Iraq in Abu Dhabi Pages 10-11 Page 20 Saudi reaction to Bab el Mandeb attack draws attention to Iranian, Houthi threats ► Experts saw Saudi Arabia as cautioning the international community against the risks posed by Iran and its Houthi proxies, whether in Yemen or in the proximity of Saudi borders. Mohammed Alkhereiji Force commander Major-General Qassem Soleimani. “The Red Sea, which was secure, London is no longer secure with the Ameri- can presence,” Soleimani said the he pro-Iran Houthi militia day after the attacks on the tank- carried through with threats ers. “[US President Donald] Trump to disrupt maritime naviga- should know we are a nation of mar- T tion in the Red Sea with at- tyrdom and that we await him.” tacks on two very large Saudi crude The Houthis had threatened to carriers. The July 25 attack, in which hinder traffic through Bab el Man- one of the two vessels was slightly deb into the Red Sea. The Iranians damaged, seemed an attempt to warned they could block shipping increase tension in the region but in the Strait of Hormuz. only to a certain point. Despite the threats and provoca- The Iranians and their proxies tions, the Iranians admit the bluster know that more serious incidents does not mean they think they can could draw a stronger international afford a war with the United States. -

Stand Alone End of Year Report Final

Shelter Cluster Yemen ShelterCluster.org 2019 Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter SHELTER CLUSTER End Year Report Shelter Cluster Yemen Foreword Yemeni people continue to show incredible aspirations and the local real estate market and resilience after ve years of conict, recurrent ood- environmental conditions: from rental subsidies ing, constant threats of famine and cholera, through cash in particular to prevent evictions extreme hardship to access basic services like threats to emergency shelter kits at the onset of a education or health and dwindling livelihoods displacement, or winterization upgrading of opportunities– and now, COVID-19. Nearly four shelters of those living in mountainous areas of million people have now been displaced through- Yemen or in sites prone to ooding. Both displaced out the country and have thus lost their home. and host communities contributed to the design Shelter is a vital survival mechanism for those who and building of shelters adapted to the Yemeni have been directly impacted by the conict and context, resorting to locally produced material and had their houses destroyed or have had to ee to oering a much-needed cash-for-work opportuni- protect their lives. Often overlooked, shelter inter- ties. As a result, more than 2.1 million people bene- ventions provide a safe space where families can tted from shelter and non-food items interven- pause and start rebuilding their lives – protected tions in 2019. from the elements and with the privacy they are This report provides an overview of 2019 key entitled to. Shelters are a rst step towards achievements through a series of maps and displaced families regaining their dignity and build- infographics disaggregated by types of interven- ing their self-reliance. -

YEMEN: Health Cluster Bulletin. 2016

YEMEN: HEALTH CLUSTER BULLETIN DECEMBER 2016 Photo credit: Qatar Red Crescent 414 health facilities Highlights operationally supported in 145 districts o From the onset of the AWD/cholera outbreak on 6 October until 20 December 406 surgical, nutrition and 2016, a cumulative number of 11,664 mobile teams in 266 districts AWD/Cholera cases and 96 deaths were reported in 152 districts. Of these, 5,739 97 general clinical and (49%) are women, while 3,947 (34%) are trauma interventions in 73 children below 5 years.* districts o The total number of confirmed measles cases in Yemen from 1 Jan to 19 December 541 child health and nutrition 2016 is 144, with 1,965 cases pending lab interventions in 323 districts confirmation.** o A number of hospitals are reporting shortages in fuel and medicines/supplies, 341 communicable disease particularly drugs for chronic illnesses interventions in 229 districts including renal dialysis solutions, medicines for kidney transplant surgeries, diabetes 607 gender and reproductive and blood pressure. health interventions in 319 o The Health Cluster and partners are working districts to adopt the Cash and Voucher program on 96 water, sanitation and a wider scale into its interventions under hygiene interventions in 77 the YHRP 2017, based on field experience districts by partners who had previously successfully implemented reproductive health services. 254 mass immunization interventions in 224 districts *WHO cholera/AWD weekly update in Yemen, 20 Dec 2016 ** Measles/Rubella Surveillance report – Week 50, 2016, WHO/MoPHP PAGE 1 Situation Overview The ongoing conflict in Yemen continues to undermine the availability of basic social services, including health services. -

Yemen Country Office

Yemen Country Office Humanitarian Situation Report ©UNICEF Yemen/2020 Reporting Period: 1 – 31 March 2021 © UNICEF/2021/Yemen Situation in Numbers (OCHA, 2021 Humanitarian Needs Overview) Highlights 11.3 million • The humanitarian situation in Ma’rib continued to be of concern, and with various children in need of waves of violence during the reporting period, the situation showed no signs of humanitarian assistance improvement. People’s lives remained to be impacted every day by fighting, and thousands were being displaced from their homes and displacement sites. Conflict continued as well as in Al Hodeidah, Taizz, and Al Jawf. 20.7 million • In March, 30,317 IDPs were displaced, with the majority of displacement waves people in need coming from Ma’rib, Al Hodeidah, Taizz and Al-Jawf, as internal displacement within governorates towards safer districts increased. • The Rapid Response Mechanism (RRM) reached an additional 3,500 newly displaced 1.58 million families, 2,200 families of which were in Ma’rib (24,500 individuals). Beneficiaries children internally displaced received RRM kits that included food, family basic hygiene kits, and female dignity kits. (IDPs) • As of 5 April 2021, there were 4,798 COVID-19 officially confirmed cases in Yemen, with 946 associated deaths and 1,738 recovered cases (resulting in a 19.7 per cent confirmed fatality rate). 382 suspected cases were health workers, or 4.78 per cent of the total cases. Funding Status UNICEF’s Response and Funding Status 2021 Appeal: $576.9M SAM Admission 15% n Funding status -

Virtual SN Health Cluster Zoom Meeting for Ibb & Taiz (OC) 13Th September, 2020

Virtual SN Health Cluster Zoom Meeting for Ibb & Taiz (OC) 13th September, 2020. Date: Sunday, 13th September,2020. Venue: Virtual Zoom Time: 10:00 AM Agenda Discussion Action Point/ Comments • Welcoming the health partners • Review of the last meeting action point Communic COVID-19 International, Regional & National Updates: • SNHC to share IU able Globally: mapping to the diseases’ • Confirmed:45,428,731 partners Situation • Total Deaths:1,185,721deaths(CFR=2.6%) • Partners to share Updates & • USA:8,852,730 the current Response • India:8,137,119 support to DTC. • Brazil:5,494,376 • UNICEF to follow EMRO: up vaccination • Confirmed:3,086,153 activities in As • Total Deaths:78,504 (CFR=2.5%) Saddah to scale up • Iran:612,772 the vaccination • Iraq:472,630 rate • KSA:347,282 • Pakistan:332,993 Yemen: • 2013 confirmed case reported in southern & eastern governorates to WHO. • 583 death • Decreasing in reported cases • The highest reported from Hadramout, Taiz ,Aden, Shabwah& Lahj Governorates • Increase in testing cases in Al Mukala & Sayon NCPHL https://covid19.who.int/ Ibb Gov. Epidemiological Updates • Cholera: The cumulative figures in IBB Governorate from 1 January to 30 Oct 2020 The cumulative figures in IBB Governorate from 1 January to 30 Oct 2020 Number Of Cases:19802 Deaths:12 Lab confirmed Cases: 2 CFR:0.06% Mainly in Females (10290 case)=60% The main reporting districts are: • Ibb • Yarim • As Saddah • As Sabrah • Jiblah • Dhi As Sufal • Al Makhadir • Hubaysh • Al Mashannah • Ar Radmah • Al Udayn Distribution of Suspected Cholera -

安全理事会 Distr.: General 30 March 2021 Chinese Original: English

联合国 S/2021/304 安全理事会 Distr.: General 30 March 2021 Chinese Original: English 2021 年 3 月 29 日也门常驻联合国代表给安全理事会主席的信 奉我国政府指示,谨随函转递关于胡塞民兵与恐怖主义组织之间合作协调情 况的报告(见附件)。* 请向安全理事会成员提供本信及其附件,供他们进行重要的审议工作,并将 本信及其附件作为安理会文件分发为荷。 常驻代表 大使 阿卜杜拉·阿里·法迪勒·萨阿迪(签名) * 仅以来件所用语文分发。 21-04250 (C) 070421 090421 *2104250* S/2021/304 2021 年 3 月 29 日也门常驻联合国代表给安全理事会主席的信的附件 [原件:阿拉伯文和英文] Republic of Yemen Central Agency for Political Security National Security Service Report on cooperation and coordination between the Houthi militia and terrorist organizations 2/24 21-04250 S/2021/304 Contents Executive summary:………………………………………………………………………………………………...6 Introduction: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………..…8 First: The goals of Houthi fallacies and allegations……...………………………………………………………8 Second: Evidence that refutes the fallacies and claims of the Houthi militia:………………………………...9 Multiple photos of the Al-Farouq School building (primary, secondary) (Al-Farouq Institute) in Karry - Marib Governorate…..….………………………………………………………………………………………..……….10 Third: The relationship of the Houthi militia with terrorist organizations…….……………………………11 A- Intelligence security cooperation: ……………………………………………………………………………12 B- The release of the organization’s operatives through premeditated escape operations:...………………13 Fourth: Some Evidence of the Relationship between the Houthi Militia and Al-Qaeda Terrorist Organization:………………………………………………………………………………………………………20 Fifth: Smuggling of Weapons and Drugs:……………………………………………………………………….20 Sixth: Military Cooperation …………………………………………………………………………………..…21 -

Yemen: Diphtheria & Cholera Response

Yemen: Diphtheria & Cholera Response Emergency Operations Center Situation Report No.19 As of 27 January 2018 1.1 Diphtheria Highlights Suspected Cholera Cases • According to MoPHP (27 January 2018), there are 849 probable diphtheria cases, including 56 associated deaths, in 143 districts among 19 governorates. • The most affected governorates are Ibb (371) and Al Hudaydah (116). Case Fatality Ratio (CFR) is 6.6%. Children under the 5 years of age represent 19% of probable cases and 36% of deaths. • Contacts traced by district RRTs in 10 governorates: 1303 (up to week 52), and 796 (weeks 1-3). • Weekly admissions to DIUs: 560 (up to week 52), 89 (week 1), and 63 (week 2). • Diphtheria Anti-Toxin (DAT) distributed per governorate: 1000 doses received in country (December 2017), with an additional 300 doses (January 2018). • Laboratory: Training on laboratory diagnosis; WHO brought reagents for culture; 17 of 47 samples collected tested positive for Albert stain and/or Gram Stain. Lab-Confirmed Cases • Penta/Td vaccination campaign strategy: Thirty-eight (38) districts with more than one case in the last 4 weeks are considered 1st priority; with a targeted number of 1,444,595 (between 6 weeks of age and 7 years of age to be vaccinated with Penta) and 1,265,771 (between > 7 years of age and 15 years of age to be vaccinated with Td) beneficiaries. Age groups of probable cases, as 0f 27 January 2018 Probable Diphtheria cases Diphtheria Deaths 1.2 Diphtheria Outbreak Response: 1.2.1 Vaccination Vaccination (Penta), November 2017 o 8,500 children (between 6 weeks of age and < 5 years of age) in the 3 most affected villages of Saddah and Yarim districts of Ibb Governorate. -

Yemen – Crisis Info December 2018

YEMEN – CRISIS INFO DECEMBER 2018 HODEIDAH On 18 September, a new offensive was launched by SELC backed forces to retake Hodeidah from Ansar Allah control after a new round of peace negotiations failed in Geneva. In mid- September, SELC-backed forces moved towards the eastern side of Hodeidah, with daily clashes partially blocking the main Hodeidah-Sanaa road and raising fears of a siege around the city. Clashes erupted on multiple occasions near the biggest hospital of the city (Al Thawrah). In August/September, a further depreciation of the Yemeni Riyal led to further increases in the price of commodities, while shortages of fuel and cooking gas were also reported. It is estimated that more than half of the 600,000 inhabitants of Hodeidah left the city, towards Sanaa, Ibb and Hajjah. In October, we also observed the return of some of them to the city due to the deteriorating economic conditions. In early October, MSF started working at Al Salakhanah hospital, northeast of the city. Teams rehabilitated the emergency room and operating theatres so as to be able to provide emergency medical and surgical care in case fighting reached new areas of the city. There is a need for healthcare, particularly trauma and surgical care. From 1 November, a stronger offensive was launched by SELC-backed forces, with deployment of troops on the ground and battles getting very close to Al Salakhana hospital, where MSF teams are working. Al Salakhana hospital remains one of only three open and operational public hospitals in the area. Al Thawrah hospital, the main public health facility in the city, is still operational but threatened by fighting and rapidly moving frontlines. -

“The Situation Needs Us to Be Active” Youth Contributions to Peacebuilding in Yemen

“The situation needs us to be active” Youth contributions to peacebuilding in Yemen December 2019 “ The situation needs us to be active” Youth contributions to peacebuilding in Yemen December 2019 Acknowledgements This paper was written by Kate Nevens, Marwa Baabbad and Jatinder Padda. They would like to thank the youth interviewees for their generous contributions of time and knowledge, as well as everyone who took the time to read and comment on earlier versions of the paper. The paper was edited by Léonie Northedge and Madeline Church, copyedited by Martha Crowley and designed by Jane Stevenson. The paper was funded by the European Commission and the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Cover photo – A young Yemeni woman stands in an abandoned building in Sana’a. © Jehad Mohammed © Saferworld, December 2019. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without full attribution. Saferworld welcomes and encourages the utilisation and dissemination of the material included in this publication. Contents Executive summary i 1 Introduction 1 2 The changing roles of youth activists: 3 a revolution and a stalled transition 3 Fight, flight or adapt: the impact of conflict 5 on activism Limited movement and ability to meet 8 Direct targeting of youth activists 8 Rising costs, loss of income and fewer resources 9 Increasing social divisions and problems engaging 9 with local authorities Strains on mental health and psychological 10 well-being 4 “The situation needs us to be active”: 13 How Yemeni youth are working towards peace “Driving peace” 14 Humanitarian relief and community organising 15 Art, peace messaging and peace education 16 Psychosocial support 17 Social entrepreneurship 18 Human rights monitoring 19 Influencing local authorities, local mediation 20 and conflict resolution Differences across locations 21 The role of Yemeni diaspora 21 5 Conclusion 25 A boy cycles past graffiti in Sana’a. -

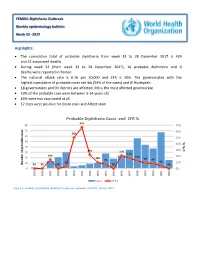

Probable Diphtheria Cases and CFR % 67% 80 70%

YEMEN: Diphtheria Outbreak Weekly epidemiology bulletin Week 52 -2017 Highlights: The cumulative total of probable diphtheria from week 33 to 29 December 2017 is 429 and 42 associated deaths. During week 52 (from week 33 to 29 December 2017), 16 probable diphtheria and 0 deaths were reported in Yemen. The national attack rate is 0.16 per 10,000 and CFR is 10%. The governorates with the highest cumulative of probable cases are Ibb (53% of the cases) and Al Hudeydah. 18 governorates and 90 districts are affected. Ibb is the most affected governorate. 50% of the probable case were between 5-14 years old 63% were not vaccinated at all. 17 tests were positive for Gram stain and Albert stain Probable Diphtheria Cases and CFR % 67% 80 70% 70 60% 50% 60 50% 50 40% 40 22% 30% CFR, % 30 21% 17% 14% 13% 20% 20 10% 7% 9% 8% 3% 4% 10% Numberof probablecases 10 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0 0% W34 W37 W38 W39 W40 W41 W42 W43 W44 W45 W46 W47 W48 W49 W50 W51 W52 W33 Cases CFR% Figure 1: number of probable diphtheria cases per epiweek, and CFR, Yemen, 2017 Geographical distribution of cases and deaths The most affected governorates are Ibb (53.9%) and Al hudaydah . Ibb has the highest attak rate (0,75 per 10 000), followed by Aden (0.30 per 10000). The highest cumulative number of deaths is in Ibb. Governorate Cases Population AR/10000 Death CFR% Ibb 226 3017004 0.75 13 6% Al Hudaydah 50 3315812 0.15 11 22% Aden 29 955022 0.30 2 7% Amran 24 1173542 0.20 3 13% Sana'a 23 1497466 0.15 0 0% Dhamar 20 2064534 0.10 2 10% Taizz 13 3056222 0.04 4 31% Hajjah 12 2442558 0.05 2 17% Amanat Al Asimah 10 2964094 0.03 0 0% Al Mahwit 4 749974 0.05 1 25% Sa'ada 4 959746 0.04 1 25% Abyan 4 583242 0.07 2 50% Lahj 3 1028118 0.03 0 0% Al Bayda 2 770358 0.03 0 0% Marib 2 368613 0.05 0 0% Hadramaut 1 1468311 0.01 0 0% Raymah 1 622106 0.02 0 0% Al Jawf 1 589320 0.02 1 100% Total 429 27626042 0.16 42 10% Table 1: Number of probable diphtheria cases and deaths, AR and CFR, per governorate, Yemen, week 33- 52, 2017 In Ibb governorates, As saddah and Yareem districts are the most affected. -

Women in Conflict Resolution and Peacebuilding in Yemen

RESEARCH PAPER WOMEN IN CONFLICT RESOLUTION AND PEACEBUILDING IN YEMEN MAHA AWADH AND NURIA SHUJA’ADEEN EDITED BY SAWSAN AL- REFAEI JANUARY 2019 © 2019 UN Women. All rights reserved. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of UN Women, the United Nations or any of its affiliated organizations. About this research paper This Research Paper was commissioned by UN Women in Yemen About the authors This paper was written by Ms. Maha Awadh and Ms. Nuria Shuja’adeen and edited by Dr. Sawsan Al-Refaei. ISBN: 978-1-63214-152-1 Suggested Citation: Awadh, M. and Shuja’adeen, N., (2019). “Women in Conflict Resolution and Peacebuilding in Yemen”. Nahj Consulting, Yemen: UN Women. Design: DammSavage Inc. RESEARCH PAPER WOMEN IN CONFLICT RESOLUTION AND PEACEBUILDING IN YEMEN MAHA AWADH AND NURIA SHUJA’ADEEN EDITED BY SAWSAN AL- REFAEI DECEMBER 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY 2 4. STORIES OF YEMENI WOMEN, CONFLICT AND PEACEBUILDING 30 4.1 SANA’A 30 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS 5 4.2 MAREB 33 4.3 SHEBWAH 34 4.4 AL-JAWF 35 LEXICON OF YEMENI ARABIC TERMINOLOGY 6 4.5 AL-BAYDHA 37 4.6 AL-DHALE’ 38 4.7 38 FOREWORD 9 TAIZ 4.8 ADEN 40 4.9 HADHRAMAWT 41 1. INTRODUCTION 10 1.1 Background on Women and Conflict in Yemen 10 CONCLUSIONS AND LESSONS LEARNED 43 1.2 Status of Women and the Impact of Conflict 12 1.3 Impact of Conflict on Gender Roles and Norms 15 1.4 Women’s Role in Decision-Making and Peacebuilding 17 APPENDIX A.