Tourist Marriage in Yemen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cholera Outbreak Weekly AWD/Cholera Situation Report 10 – 17 November 2016

YEMEN: Cholera Outbreak Weekly AWD/Cholera Situation Report 10 – 17 November 2016 This official joint-report is based on information Yemen Cholera Taskforce, which is led by the Ministry of Health, WHO/Health Cluster, UNICEF/WASH Cluster and is supported by OCHA. Key Figures As of 17 November 2016, 90 Al Jawf Aflah Ash Shawm Khamir Kuhlan Ash Sharaf Abs Amran cases of cholera were confirmed Hajjah Al Miftah Hadramaut Ash Shahil Az Zuhr Arhab Nihm A ah Sharas in 29 districts with 8 cases of lluh ey ah Bani Qa'is HamdanBani Al Harith Marib deaths from cholera. Amanat Al AsimahBani Hushaysh Al Mahwit Ma'ain Sana'a Az Zaydiyah As Sabain n Khwlan As Salif a h n a S WHO/ MoPHP estimates that Bajil As Salif ra Al Marawi'ah Bu Al Mina Shabwah 7.6M people are at risk in 15 Al HaliAl Hudaydah Al Hawak Al MansuriyahRaymah Ad Durayhimi Dhamar governorates. iah aq l F h t A a ay y B r Y a a r h im S Al Bayda bid Za h s A total of 4,825 suspected cases A Hazm Al Udayn HubayshAl Makhadir Ibb Ash Sha'ir ZabidJabal Ra's s Ibb Ba'dan ra Qa'atabah Al Bayda City ay Hays Al Udayn uk are reported in 64 districts. JiblahAl Mashannah M Far Al Udayn Al Dhale'e M Dhi As SufalAs Sayyani a Ash Shu'ayb Al Khawkhah h a As Sabrah s Ad Dhale'e q u Al Hussein b H Al Khawkhah a Jahaf n l Abyan a A Cholera case fatality rate (CFR) h Al Azariq a h k u Mawza M TaizzJabal Habashy l A is 1.5 % Al Milah Al Wazi'iyah Lahj T u Al Hawtah Tur A b Incidence rate is 4 cases per l Bah a a h n Dar Sad Khur Maksar Al Madaribah Wa Al Arah Aden Al Mansura 10,000. -

Arabs at the Crossroads: Political Identity and Nationalism

Book Review of Hilal Khashan's Arabs at the Crossroads: Political Identity and Nationalism (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2000), The Arab World Geographer/Le Géographe du monde arabe 3(2):141-147, 2000. In the book Arabs at the Crossroads, Hilal Khashan, an associate professor of political science at the American University of Beirut, provides a vivid description of Arab political performance since the decline of the Ottoman Empire in the nineteenth century and the subsequent formal abrogation of the Islamic Caliphate in 1924 amidst rising European colonialism and Zionism. The book is small (149 pages of text) but concise and well written. Despite raising some very controversial issues, Khashan has combined the coolness of scholarship with intellectual rigor and political concern. His dispassionate perspective is refreshing and makes the book unapologetically independent and provocative. The book consists of nine chapters mostly focused on Arab political experience during the twentieth century. Chapter 1 examines the roots of the identity crisis in the Arab world, especially the ways in which “nineteenth-century reformers disturbed the Arab mind by sowing distrust in the Ottoman empire, without securing a tenable ideological alternative to that religious state and to Islam which it embodied” (page 1). Chapter 2 discusses the birth and the universalization of the European nation-state model of secular nationalism and its many incomplete versions in non-Western cultures, particularly in Muslim countries where “the clash between ethnocentrism and religion seems to resolve itself to the detriment of the former, without the latter emerging as a clear victor” (page 24). While this is a brilliant description of how modern Arab identity seems to swing constantly from Arab nationalism to Islamic identity and back, it stops short of an in-depth theoretical analysis of what constitutes the essence of identity in the Arab world. -

Stand Alone End of Year Report Final

Shelter Cluster Yemen ShelterCluster.org 2019 Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter SHELTER CLUSTER End Year Report Shelter Cluster Yemen Foreword Yemeni people continue to show incredible aspirations and the local real estate market and resilience after ve years of conict, recurrent ood- environmental conditions: from rental subsidies ing, constant threats of famine and cholera, through cash in particular to prevent evictions extreme hardship to access basic services like threats to emergency shelter kits at the onset of a education or health and dwindling livelihoods displacement, or winterization upgrading of opportunities– and now, COVID-19. Nearly four shelters of those living in mountainous areas of million people have now been displaced through- Yemen or in sites prone to ooding. Both displaced out the country and have thus lost their home. and host communities contributed to the design Shelter is a vital survival mechanism for those who and building of shelters adapted to the Yemeni have been directly impacted by the conict and context, resorting to locally produced material and had their houses destroyed or have had to ee to oering a much-needed cash-for-work opportuni- protect their lives. Often overlooked, shelter inter- ties. As a result, more than 2.1 million people bene- ventions provide a safe space where families can tted from shelter and non-food items interven- pause and start rebuilding their lives – protected tions in 2019. from the elements and with the privacy they are This report provides an overview of 2019 key entitled to. Shelters are a rst step towards achievements through a series of maps and displaced families regaining their dignity and build- infographics disaggregated by types of interven- ing their self-reliance. -

On Conservation and Development: the Role of Traditional Mud Brick Firms in Southern Yemen*

On Conservation and Development: The Role of Traditional Mud Brick Firms in Southern Yemen* Deepa Mehta Graduate School of Architecture, Planning & Preservation** Columbia University in the City of New York New York, NY 10027, USA [email protected] ABSTRACT A study of small and medium enterprises that make up the highly specialized mud brick construction industry in southern Yemen reveals how the practice has been sustained through closely-linked regional production chains and strong firm inter-relationships. Yemen, as it struggles to grow as a nation, has the potential to gain from examining the contribution that these institutions make to an ancient building practice that still continues to provide jobs and train new skilled workers. The impact of these firms can be bolstered through formal recognition and capacity development. UNESCO, ICOMOS, and other conservation agencies active in the region provide a model that emphasizes architectural conservation as well as the concurrent development of the existing socioeconomic linkages. The primary challenge is that mud brick construction is considered obsolete, but evidence shows that the underlying institutions are resilient and sustainable, and can potentially provide positive regional policy implications. Key Words: conservation, planning, development, informal sector, capacity building, Yemen, mud brick construction. * Paper prepared for GLOBELICS 2009: Inclusive Growth, Innovation and Technological Change: education, social capital and sustainable development, October 6th – -

Prisons in Yemen

[PEACEW RKS [ PRISONS IN YEMEN Fiona Mangan with Erica Gaston ABOUT THE REPORT This report examines the prison system in Yemen from a systems perspective. Part of a three-year United States Institute of Peace (USIP) rule of law project on the post-Arab Spring transition period in Yemen, the study was supported by the International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Bureau of the U.S. State Department. With permission from the Yemeni Ministry of Interior and the Yemeni Prison Authority, the research team—authors Fiona Mangan and Erica Gaston for USIP, Aiman al-Eryani and Taha Yaseen of the Yemen Polling Center, and consultant Lamis Alhamedy—visited thirty-seven deten- tion facilities in six governorates to assess organizational function, infrastructure, prisoner well-being, and security. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Fiona Mangan is a senior program officer with the USIP Governance Law and Society Center. Her work focuses on prison reform, organized crime, justice, and security issues. She holds degrees from Columbia University, King’s College London, and University College Dublin. Erica Gaston is a human rights lawyer with seven years of experience in programming and research in Afghanistan on human rights and justice promotion. Her publications include books on the legal, ethical, and practical dilemmas emerging in modern conflict and crisis zones; studies mapping justice systems and outcomes in Afghanistan and Yemen; and thematic research and opinion pieces on rule of law issues in transitioning countries. She holds degrees from Stanford University and Harvard Law School. Cover photo: Covered Yard Area, Hodeida Central. Photo by Fiona Mangan. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors alone. -

Women and Peacebuilding in Yemen: Challenges and Opportunities by Najwa Adra

Expert Analysis November 2013 Women and peacebuilding in Yemen: challenges and opportunities By Najwa Adra Executive summary This expert analysis explores hurdles facing and opportunities available to Yemeni women in light of UN Security Council Resolution 1325’s guidelines. Yemen is rich in social capital with norms that prioritise the protection of women, but internal and external stresses pose serious threats to women’s security. Despite these hurdles, Yemeni women continue to participate in nation building. In 2011 women led the demonstrations that ousted the previous regime. At 27%, women’s representation and leadership in the current National Dialogue Conference is relatively inclusive. Their calls for 30% women’s participation in all levels of government have passed despite the opposition of religious extremists and the Yemeni Socialist Party. To provide the best guarantee of women’s security in Yemen, international agencies must, firstly, pressure UN member states to desist from escalat- ing conflicts in Yemen, and secondly, prioritise development over geopolitical security concerns. Literate women with access to health care and marketable skills can use their participatory traditions to build a new Yemeni nation. United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 (UNSCR government headed by Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi, Yemen’s 1325) has succeeded in inserting discussion of women’s former vice-president. A National Dialogue Conference concerns into Security Council discourse. Its charge to (NDC) composed of representatives from established increase representation for women at all levels of peace- political parties, including that of the former president, building and include gender perspectives in programming youth, women, and marginalised groups, has been charged and support have led to national action plans and success- with developing a framework for a new Yemeni state. -

Common Misconceptions and Stereotypes About the Middle East

Common Misconceptions and Stereotypes about the Middle East The Middle East does not have clear-cut boundaries. There are cross-cultural connections that stretch from North Africa through Western Asia into Central Asia. The most basic map of the Middle The Middle East is a clearly defined East includes Bahrain, Cyprus, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, the Palestinian Territories, Qatar, Saudi place. Arabia, Syria, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. People in the Middle East live as nomads. Very few people in the Middle East live as nomads. The Middle East is quite urbanized and has some of the oldest cities in the world. There is nothing but desert and oil in 60% of the region’s population lives in major cities such as the Middle East. Damascus, Istanbul and Cairo. Ancient Middle Eastern kingdoms such as Sumer, Babylon and Egypt were all cradles for western The Middle East and the Islamic World civilization. are the same. Everyone in the Middle East speaks There is more than desert and oil in the Middle East. The geography of the Middle East is diverse and includes everything from fertile Arabic. river deltas and forests, to mountain ranges and arid plateaus. Some Everyone in the Middle East is Muslim. countries in the Middle East are oil rich, while others have little or no All Arabs are Muslim. oil reserves. Violence in the Middle East is The Middle East and the Islamic World are not the same. While inevitable. Islam first developed in the Arabian Peninsula and Arabic is its Everyone in the Middle East hates the liturgical language, the majority of the world’s Muslims are not Arab and live outside the Middle East. -

“The Sorrows of Egypt,” Revisited in Knowledge He Sought Years Idol Masses

A HOOVER INSTITUTION ESSAY on A us strateGIC vision in A CHANGING WORLD “The Sorrows of Egypt,” Revisited SAMUEL TADROS The sorrow of Egypt is made of entirely different material: the steady decline of its public life, the inability of an autocratic regime and of the middle class from which this regime issues to rid the country of its dependence on foreign handouts, to transmit to the vast underclass the skills needed for the economic competition of nations; to take the country beyond its endless alternations between glory and self-pity. (Fouad Ajami, “The Sorrows of Egypt”) In his authoritative 1995 essay “The Sorrows of Egypt,”1 Fouad Ajami, with the knowledge and experience of someone who had known Egypt intimately, and the spirit and pen of a poet who had come to love the place, attempted to delve deeply into what ailed the ancient land. The essay moved masterfully from the political to the social and Islamism and the International Order International the and Islamism from the religious to the economic, weaving an exquisite tapestry of a land of sorrows. This was not the first time that Ajami had approached Egypt. The country his generation had grown up knowing was the Egypt of promise and excitement, where Gamal Abdel Nasser’s towering presence and deep voice had captivated millions of Arabic speakers. Ajami had been one of those young men. He had made the pilgrimage to Damascus, watching and cheering as Nasser made his triumphant entry into the city in 1958, crowned as the idol of the Arabs by adoring masses. -

Inter-Agency Joint Cash Study: Market Functionality and Community Perception of Cash Based Assistance

INTER-AGENCY JOINT CASH STUDY: MARKET FUNCTIONALITY AND COMMUNITY PERCEPTION OF CASH BASED ASSISTANCE YEMEN REPORT DECEMBER 2017 Inter-Agency Joint Cash Study - 2017 Cash and Market Working Group Partners The following organisations contributed to the production of this report, as members of the Cash and Market Working Group for Yemen (CMWG) 1 Inter-Agency Joint Cash Study - 2017 Cover Image: OCHA/ Charlotte Cans, Sana’a, June 2015. https://ocha.smugmug.com/Countries/Yemen/General-views-Sanaa/i-CrmGpCB About REACH REACH facilitates the development of information tools and products that enhance the capacity of aid actors to make evidence-based decisions in emergency, recovery and development contexts. All REACH activities are conducted through inter-agency aid coordination mechanisms. For more information, you can write to our in-country office: [email protected]. You can view all our reports, maps and factsheets on our resource centre: reachresourcecentre.info, visit our website at reach-initiative.org, and follow us @REACH_info 2 Inter-Agency Joint Cash Study - 2017 SUMMARY Since 2015, conflict in Yemen has left 3 million people displaced and over half of the population food insecure, and has destroyed much of the country’s infrastructure1. As of July 2017, much of the population had lost their primary source of income, 46% lacked access to a free improved water source2, and an outbreak of cholera had become the largest in modern history.3 The Cash and Market Working Group (CMWG) estimated that in 2016, cash transfer programmes were conducted in 22 governorates across Yemen; however, it found little evidence to determine which method of financial assistance is the most suitable in the context of Yemen. -

Bibliographic Annual in Speech Communication 1973

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 088 129 CS 500 620 AUTHOR Kennicott, Patrick C., Ed. TITLE Bibliographic Annual in Speech Communication 1573. INSTITUTION Speech Communication Association, New York, N.Y. PUB DATE 74 NOTE 267p. AVAILABLE FROM Speech. Communication Association, Statler Hiltcn Hotel, New York, N. Y. 10001 ($8.00). EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$12.60 DESCRIPTORS *Behavioral Science Research; *Bibliographies; *Communication Skills; Doctoral Theses; Literature Reviews; Mass Media; Masters Theses; Public Speaking; Research Reviews (Publications); Rhetoric; *Speech Skills; *Theater Arts IDENTIFIERS Mass Communication; Stagecraft ABSTRACT This volume contains five subject bibliographies for 1972, and two lists of these and dissertations. The bibliographies are "Studies in Mass Communication," "Behavioral Studies in Communication," "Rhetoric and Public Address," "Oral Interpretation," and "Theatrical Craftsmanship." Abstracts of many of the doctcral disertations produced in 1972 in speech communication are arranged by subject. ALso included in a listing by university of titles and authors of all reported masters theses and doctoral dissertaticns completed in 1972 in the field. (CH) U S Ol l'AerVE NT OF MEAL.TH r DUCA ICON R ,Stl. I, AWE NILIONAt. INST I IUI EOF E DOCA I ION BIBLIOGRAPHIC ANNUAL CO IN CD SPEECH COMMUNICATION 1973 STUDIES IN MASS COMMUNICATION: A SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY, 1972 Rolland C. Johnson BEHAVIORAL STUDIES IN COMMUNICATION, 1972 A SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY Thomas M. Steinfatt A SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF RHETORIC AND PUBLIC ADDRESS, 1972 Harold Mixon BIBLIOGRAPHY OF STUDIES IN ORAL INTERPRETATION, 1972 James W. Carlsen A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF THEATRICAL CRAFTSMANSHIP, 1972. r Christian Moe and Jay E. Raphael ABSTRACTS OF DOCTORAL DISSERTATIONS IN THE FIELD OF SPEECH COMMUNICATION, 1972. -

YEMEN: Health Cluster Bulletin. 2016

YEMEN: HEALTH CLUSTER BULLETIN DECEMBER 2016 Photo credit: Qatar Red Crescent 414 health facilities Highlights operationally supported in 145 districts o From the onset of the AWD/cholera outbreak on 6 October until 20 December 406 surgical, nutrition and 2016, a cumulative number of 11,664 mobile teams in 266 districts AWD/Cholera cases and 96 deaths were reported in 152 districts. Of these, 5,739 97 general clinical and (49%) are women, while 3,947 (34%) are trauma interventions in 73 children below 5 years.* districts o The total number of confirmed measles cases in Yemen from 1 Jan to 19 December 541 child health and nutrition 2016 is 144, with 1,965 cases pending lab interventions in 323 districts confirmation.** o A number of hospitals are reporting shortages in fuel and medicines/supplies, 341 communicable disease particularly drugs for chronic illnesses interventions in 229 districts including renal dialysis solutions, medicines for kidney transplant surgeries, diabetes 607 gender and reproductive and blood pressure. health interventions in 319 o The Health Cluster and partners are working districts to adopt the Cash and Voucher program on 96 water, sanitation and a wider scale into its interventions under hygiene interventions in 77 the YHRP 2017, based on field experience districts by partners who had previously successfully implemented reproductive health services. 254 mass immunization interventions in 224 districts *WHO cholera/AWD weekly update in Yemen, 20 Dec 2016 ** Measles/Rubella Surveillance report – Week 50, 2016, WHO/MoPHP PAGE 1 Situation Overview The ongoing conflict in Yemen continues to undermine the availability of basic social services, including health services. -

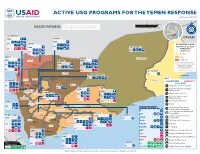

USG Yemen Complex Emergency Program

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS FOR THE YEMEN RESPONSE Last Updated 02/12/20 0 50 100 mi INFORMA Partner activities are contingent upon access to IC TI PH O A N R U G SAUDI ARABIA conict-aected areas and security concerns. 0 50 100 150 km N O I T E G U S A A D ID F /DCHA/O AL HUDAYDAH IOM AMRAN OMAN IOM IPs SA’DAH ESTIMATED FOOD IPs SECURITY LEVELS IOM HADRAMAWT IPs THROUGH IPs MAY 2020 IPs Stressed HAJJAH Crisis SANA’A Hadramawt IOM Sa'dah AL JAWF IOM Emergency An “!” indicates that the phase IOM classification would likely be worse IPs Sa'dah IPs without current or planned IPs humanitarian assistance. IPs Source: FEWS NET Yemen IPs AL MAHRAH Outlook, 02/20 - 05/20 Al Jawf IP AMANAT AL ASIMAH Al Ghaedha IPs KEY Hajjah Amran Al Hazem AL MAHWIT Al Mahrah USAID/OFDA USAID/FFP State/PRM Marib IPs Hajjah Amran MARIB Agriculture and Food Security SHABWAH IPs IBB Camp Coordination and Camp Al Mahwit IOM IPs Sana'a Management Al Mahwit IOM DHAMAR Sana'a IPs Cash Transfers for Food Al IPs IPs Economic Recovery and Market Systems Hudaydah IPs IPs Food Voucher Program RAYMAH IPs Dhamar Health Raymah Al Mukalla IPs Shabwah Ataq Dhamar COUNTRYWIDE Humanitarian Coordination Al Bayda’ and Information Management IP Local, Regional, and International Ibb AD DALI’ Procurement TA’IZZ Al Bayda’ IOM Ibb ABYAN IOM Al BAYDA’ Logistics Support and Relief Ad Dali' OCHA Commodities IOM IOM IP Ta’izz Ad Dali’ Abyan IPs WHO Multipurpose Cash Assistance Ta’izz IPs IPs UNHAS Nutrition Lahij IPs LAHIJ Zinjubar UNICEF Protection IPs IPs WFP Ready-to-Use Therapeutic Food IOM Al-Houta ADEN FAO Refugee and Migrant Assistance IPs Aden IOM UNICEF Risk Management Policy and Practice Shelter and Settlements IPs WFP SOCOTRA DJIBOUTI, ETHIOPIA, U.S.