Zufall,William R-The Morgan Affair

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Surname First JMA# Death Date Death Location Burial Location Photo

Surname First JMA# Death date Death location Burial Location Photo (MNU) Emily R45511 December 31, 1963 California? Los Molinos Cemetery, Los Molinos, Tehama County, California (MNU) Helen Louise M515211 April 24, 1969 Elmira, Chemung County, New York Woodlawn National Cemetery, Elmira, Chemung County, New York (MNU) Lillian Rose M51785 May 7, 2002 Las Vegas, Clark County, Nevada Southern Nevada Veterans Memorial Cemetery, Boulder City, Nevada (MNU) Lois L S3.10.211 July 11, 1962 Alhambra, Los Angeles County, California Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, Los Angeles County, California Ackerman Seymour Fred 51733 November 3, 1988 Whiting, Ocean County, New Jersey Cedar Lawn Cemetery, Paterson, Passaic County, New Jersey Ackerman Abraham L M5173 October 6, 1937 Paterson, Passaic County, New Jersey Cedar Lawn Cemetery, Paterson, Passaic County, New Jersey Ackley Alida M5136 November 5, 1907 Newport, Herkimer County, New York Newport Cemetery, Herkimer, Herkimer County, New York Adrian Rosa Louise M732 December 29, 1944 Los Angeles County, California Fairview Cemetery, Salida, Chaffee County, Colorado Alden Ann Eliza M3.11.1 June 9, 1925 Chicago, Cook County, Illinois Rose Hill Cemetery, Chicago, Cook County, Illinois Alexander Bernice E M7764 November 5, 1993 Whitehall, Pennsylvania Walton Town and Village Cemetery, Walton, Delaware County, New York Allaben Charles Moore 55321 April 12, 1963 Binghamton, Broome County, New York Vestal Hills Memorial Park, Vestal, Broome County, New York Yes Allaben Charles Smith 5532 December 12, 1917 Margaretville, -

Craft Masonry in Genesee & Wyoming County, New York

Craft Masonry in Genesee & Wyoming County, New York Compiled by R.’.W.’. Gary L. Heinmiller Director, Onondaga & Oswego Masonic Districts Historical Societies (OMDHS) www.omdhs.syracusemasons.com February 2010 Almost all of the land west of the Genesee River, including all of present day Wyoming County, was part of the Holland Land Purchase in 1793 and was sold through the Holland Land Company's office in Batavia, starting in 1801. Genesee County was created by a splitting of Ontario County in 1802. This was much larger than the present Genesee County, however. It was reduced in size in 1806 by creating Allegany County; again in 1808 by creating Cattaraugus, Chautauqua, and Niagara Counties. Niagara County at that time also included the present Erie County. In 1821, portions of Genesee County were combined with portions of Ontario County to create Livingston and Monroe Counties. Genesee County was further reduced in size in 1824 by creating Orleans County. Finally, in 1841, Wyoming County was created from Genesee County. Considering the history of Freemasonry in Genesee County one must keep in mind that through the years many of what originally appeared in Genesee County are now in one of other country which were later organized from it. Please refer to the notes below in red, which indicate such Lodges which were originally in Genesee County and would now be in another county. Lodge Numbers with an asterisk are presently active as of 2004, the most current Proceedings printed by the Grand Lodge of New York, as the compiling of this data. Lodges in blue are or were in Genesee County. -

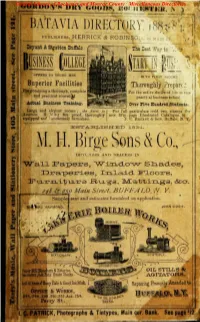

KM. H. Birge Sons & Co

Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Miscellaneous Directories S DRY GOOD^KQfjiEgTISB. \ PUBLISHERS, HERRICK & ROBINSO.s, ea Bryant & Styatton Buffalo The Lest 7,ray to \'.-: OPFEK8 TO YODNG MEN IS TO FIBST J6.COME Superior Facilities Thoroughly 'Prepare! For obtaining a thorough, complete For the active duties of life nt tins and practical course^kf practical business School. Actual Business Training. Over Five Hundred Students. Ij&rge and elegant rooms ; the finest in For full particulars send two stamps frr America. Bulging flre proof, thoroughly new fifty page Illustrated Catalogue to equipped and ; audsomely furnished. J. C. BRYANT & SON, Buffalo, N. Y. ESTABLISHED 183-i. KM. H. Birge Sons & Co., iMro.rriiRK AND DEALERS IN "Wall Papers, 'W±xi.clo-'w- Slxacies, Draperies, IxLla-xd- Floors, Fu.mitu.ra JEIXJL^S^ is/E&.'b'bi.-n.gs, &o. 248 QL 250 Main Street, BUFFALO, N. Y. sent and estiiiiates furuislied on application. I RI#.VRO HAMMOND, JOHN COON. f VI S Paper Mill Bleachers & Eotanes. OIL STILLS & SlP Smote Stacks AGITATORS. } Repairing Promptly Attendoi to. OFFICE & WORKS, 244.246.248.250.252.And.254. b To""'ro"o"o'o.B''|S- - Perry St. M I. p, PATRICK, Photographs & Tintypes, Main cor. Bank. See page '12 ; Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Miscellaneous Directories Rochester Public Library Bur Reference Book CcL Not For Circulation EAST MAIN THE LARGEST AND MOST RELIABLE WHOLESALE AND RETAIL Dry Goods & Carpet House In Western New York. Purchasing Offices in NEIV YORK, PARISH BERLIN ALL THE LATEST NOVELTIES IN BOTH LADIES' AND GENTLE- MEN'S GOODS CONSTANTLY ON HAND. -

H. Doc. 108-222

Biographies 995 Relations, 1959-1973; elected as a Republican to the Eighty- ty in 1775; retired from public life in 1793; died in fifth and to the seven succeeding Congresses (January 3, Windham, Conn., May 13, 1807; interment in Windham 1957-January 3, 1973); was not a candidate for reelection Cemetery. in 1972 to the Ninety-third Congress; retired and resided Bibliography: Willingham, William F. Connecticut Revolutionary: in Elizabeth, N.J., where she died February 29, 1976; inter- Eliphalet Dyer. Hartford: American Revolutionary Bicentennial Commission ment in St. Gertrude’s Cemetery, Colonia, N.J. of Connecticut, 1977. DYAL, Kenneth Warren, a Representative from Cali- DYER, Leonidas Carstarphen (nephew of David Patter- fornia; born in Bisbee, Cochise County, Ariz., July 9, 1910; son Dyer), a Representative from Missouri; born near attended the public schools of San Bernardino and Colton, Warrenton, Warren County, Mo., June 11, 1871; attended Calif.; moved to San Bernardino, Calif., in 1917; secretary the common schools, Central Wesleyan College, Warrenton, to San Bernardino, County Board of Supervisors, 1941-1943; Mo., and Washington University, St. Louis, Mo.; studied served as a lieutenant commander in the United States law; was admitted to the bar in 1893 and commenced prac- Naval Reserve, 1943-1946; postmaster of San Bernardino, tice in St. Louis, Mo.; served in the Spanish-American War; 1947-1954; insurance company executive, 1954-1961; mem- was a member of the staff of Governor Hadley of Missouri, ber of board of directors -

BATAVIA SUBJECT LISTING ARTISTS/G-L Cont

BATAVIA SUBJECT LISTING ARTISTS/G-L Cont. Long, Sharon Letter “A” Luplow, Eric AGRICULTURE ARTISTS/M-Z AIRPLANE, DIRIGIBLE MacPherson, Thomas Mager, Kay AMBULANCE SERVICE Mahaney, George ANIMALS/PETS & WILD Maniace, John Marmo, Chuck TH ANNIVERSARY/ 50 1965 McPherson, John ANNIVERSARY/ 75TH 1990 Meisner, Joyce Miconi, Michael TH ANNIVERSARY/ 100 2015 CITY Morasco, Alyssa ANNIVERSARY/ 100TH 1902 TOWN Munford, Virginia Nigro-Hill, Shirley TH ANNIVERSARY/ 200 2001 TOWN Pardee, Mrs. F. C. ARCHEOLOGY Putnam, R. Josiah Reilly, Patrick ARSENAL Reisdorf, Karen ARTISTS/A-F Rindo, Robert & Carol Askins, Willie Schirm, David Beers, Thom Shultz, Eric Buckman, Jolene Skelton, Mary Burr, Patricia Slivinski, Stanley Carmichael, Don VonKramer, Esther Creps, Gerald Walker, Sean D’Agostino, Robert Ware, Richard DeFelice, Cindy Whalen, Joseph Del Plato, Vincenzo Wozniak, Judy Dentino, Colin Yasses, Henry Dicarlo, Rosa ARTISTS, SOCIETY OF/Thru 2010 Dumuhosky, Rob Edwards, George ARTISTS, SOCIETY OF/2011- Embroli, Enrico ARTISTS, SOCIETY OF/Pamphlets Feary, Kevin AUTHORS ARTISTS/GENERAL AWARDS ARTISTS/G-L Garver, Walt Letter “B” Gemperlein, Elizabeth BALLOONING Gluck, Lorraine Graczyk, Carolyn BANKING /BANK OF BATAVIA Hammon, Kevin BANKING/BANK OF GENESEE, #1 (Genesee Trust) Hayes, Rosalind Hilchey, Dorothy BANKING/BANK OF GENESEE, #2 (Genesee Trust) Hodgins, John BANKING/GENERAL/- 2014 Judd, Mrs. Milo Bank of Castile Kelsey, Anna Citifinancial Koert, Bernadine ESL Federal Credit Union Kuchera, John Five Star Langen, Peter Genesee County Savings & Loan LeClear, Thomas Hudson City Bancorp BANKING/GENERAL/-2014 Cont. BUSINESS/AGRICULTURAL IMPLEMENTS HSBC Agway Key Cedar St. Sales & Rental Legend Group Central Tractor Lockport Savings Corcoran’s Custom Services LPL Financial Country Lawn & Garden M & T Day & Perkins Marine Midland Geer Farm Services Inc. -

History of Batavia 1801 to 2015

HISTORY OF BATAVIA 1801 TO 2015 Larry Dana Barnes Batavia City Historian 2015 Dedication This book is dedicated to future Batavians who may read this publication years into the future. May they find it both interesting and useful. Author . Larry Dana Barnes is the current historian for the City of Batavia, New. York, a position . mandated by State law. Bom on October 19, 1940 in Dansville; New York, he grew up in . Jamestown. He is a graduate of Jamestown High School,Jamestown Community College, Harpur College, State University of Iowa, and, most recently, Genesee Community College. The author taught courses in psychology while serving on the faculty of Mohawk Valley Community College in Utica, New York from 1966 to 1968 and then at Genesee Community College from· 1968 until his retirement in 2005. After earning an associate's degree from G.C.C.; he also taught courses in industrial model-making. Although formally educated primarily in the field of psychology, the author had along-term interest in history prior to being appointed as the Batavia City Historian in 2008. In addition to being the City Historian, he has served as President of the landmark Society of Genesee County, is a member of the Batavia Historic Preservation Commission, and works as a volunteer in the Genesee County History Department. He also belongs to the Genesee County Historians . Association, Government Appointed Historians of Western New York, and the Association of Public Historians of New York State. The author is married to. Jerianne Louise Barnes, his wife ofSO years and a retired public school librarian who operated a genealogical research service prior to herretirement. -

Exhibit 24. Visual Impacts.Pdf

EXCELSIOR ENERGY CENTER Case No. 19-F-0299 1001.24 Exhibit 24 Visual Impacts Contents Exhibit 24: Visual Impacts ............................................................................................................. 1 24(a) Visual Impact Assessment ............................................................................................ 1 (1) Character and Visual Quality of the Existing Landscape ........................................... 2 (2) Visibility of the Project ................................................................................................ 6 (3) Visibility of Aboveground Interconnections and Roadways ....................................... 9 (4) Appearance of the Facility Upon Completion ........................................................... 10 (5) Lighting .................................................................................................................... 12 (6) Photographic Overlays and LOS ............................................................................. 12 (7) Nature and Degree of Visual Change from Construction ......................................... 20 (8) Nature and Degree of Visual Change from Operation ............................................. 20 (9) Measures to Mitigate for Visual Impacts .................................................................. 24 (10) Description of Visual Resources to be Affected ....................................................... 26 24(b) Viewshed Analysis ..................................................................................................... -

H. Doc. 108-222

1406 Biographical Directory Fifty-third, and Fifty-fourth Congresses (March 4, 1891- Ill., and again engaged in banking; died in Evanston, Ill., March 3, 1897); was not a candidate for renomination in October 2, 1916; interment in Maple Hill Cemetery, Char- 1896; resumed the practice of law and also engaged in bank- lotte, Mich. ing in Sardis; retired from active business pursuits in 1912; died in Sardis, Miss., July 6, 1913; interment in Rosehill LACEY, John Fletcher, a Representative from Iowa; Cemetery. born in New Martinsville, Va. (now West Virginia), May 30, 1841; moved to Iowa in 1855 with his parents, who KYLE, Thomas Barton, a Representative from Ohio; settled in Oskaloosa; attended the common schools and pur- born in Troy, Miami County, Ohio, March 10, 1856; attended sued classical studies; engaged in agricultural pursuits; the public schools and Dartmouth College, Hanover, N.H.; learned the trades of bricklaying and plastering; enlisted studied law; was admitted to the bar in 1884 and com- in Company H, Third Regiment, Iowa Volunteer Infantry, menced practice in Troy; elected prosecuting attorney of in May 1861 and afterward served in Company D, Thirty- Miami County in 1890; president of the board of education third Regiment, Iowa Volunteer Infantry, as sergeant major, of Troy; mayor of Troy; elected as a Republican to the Fifty- and as lieutenant in Company C of that regiment; promoted seventh and Fifty-eighth Congresses (March 4, 1901-March to assistant adjutant general; studied law; was admitted 3, 1905); was an unsuccessful candidate for renomination to the bar in 1865 and commenced practice in Oskaloosa, in 1904; resumed the practice of his profession in Troy, Iowa; member of the Iowa house of representatives in 1870; Ohio, where he died on August 13, 1915; interment in River- elected city councilman in 1880; served one term as city side Cemetery. -

H. Doc. 108-222

Biographies 2097 renomination; was appointed a commissioner to adjust the Hanover County, N.C.; clerk of a court of equity 1858-1861; claims of the Choctaw Indians in 1837; elected as a Demo- delegate to the Constitutional Union National Convention crat to the Twenty-sixth Congress (March 4, 1839-March at Baltimore in 1860; engaged in newspaper work; edited 3, 1841); unsuccessful candidate for reelection in 1840 to the Wilmington Daily Herald in 1860 and 1861; served as the Twenty-seventh Congress; moved to Trenton, N.J., and lieutenant colonel of the Third Cavalry, Forty-first North resumed the practice of law; delegate to the State constitu- Carolina Regiment, during the Civil War; elected as a Demo- tional convention in 1844; appointed chief justice of the su- crat to the Forty-second and to the three succeeding Con- preme court of New Jersey in 1853, but declined; appointed gresses (March 4, 1871-March 3, 1879); chairman, Com- Minister to Prussia on May 24, 1853, and served until Au- mittee on Post Office and Post Roads (Forty-fifth Congress); gust 10, 1857; again resumed the practice of law; delegate unsuccessful candidate for reelection in 1878 to the Forty- to the peace convention held in Washington, D.C., in 1861 sixth Congress; resumed the practice of law and also en- in an effort to devise means to prevent the impending war; gaged in literary pursuits; editor of the Charlotte Journal- reporter of the supreme court of New Jersey 1862-1872; Observer in 1881 and 1882; delegate to the Democratic Na- commissioner of the sinking fund of New Jersey from 1864 tional Conventions in 1880 and 1896; mayor of Wilmington until his death; died in Trenton, N.J., November 18, 1873; 1898-1904; died in Wilmington, N.C., March 17, 1912; inter- interment in the cemetery of the First Reformed Dutch ment in Oakdale Cemetery. -

Anti-Masonic Period 1826 Thru Civil

SECTION 4 Section 4 Anti-Masonic Period = 1826 thru Civil War 269 TWO FACES Fig. 1 — The 9/11/1826 abduction and murder of Royal Arch Mason William Morgan triggered the Anti-Masonic Movement. Complete story is in two new chapters in the 3rd edition of Scarlet and Beast, Vol. 1, chps. 13-14; The Morgan Affair Triggers the Anti-Masonic Movement and the American Masonic Civil War. 13O Royal Arch Mason (renounced) CAPTAIN WILLIAM MORGAN Murdered by Freemasons in 1826 for Revealing the Secrets of Freemasonry 10,000 Famous Freemasons, by 33O William R. Denslow, reports, "His disappearance gave rise to the Anti-Masonic party, 141 Anti-Masonic newspapers in the U.S.A., and almost killed Freemasonry in America." 270 SECTION 4 Figure 2 — This book contains court transcripts of testimonies given by named witnesses to the abduction & murder of William Morgan. First published in 1965 and reprinted in 1974. It is now out of print. It contains the court records, transcripts, and testimonies of witnesses to the abduction and Masonic murder of William Morgan. You can read the entire story in Scarlet and the Beast, Vol. 1, 3rd edition, chapter 13. 271 TWO FACES Fig. 3 — Aug. 9, 1826 an advertisement was inserted in a paper printed in Canandaigua. Copy below. The message is only for Masons to understand. Read the decoded message in Scarlet and the Beast, Vol. 1, 3rd ed., ch. 13. Figure 4 — Abduction of Captain William Morgan by Masons Great Kidnapping Furor took place in 1826 over the disappearance of William Morgan, a renegade Mason who was supposedly abducted and then killed by Masons. -

The Anti-Masonic Party in the United States: 1826-1843

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Political History History 1983 The Anti-Masonic Party in the United States: 1826-1843 William Preston Vaughn North Texas State University Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Vaughn, William Preston, "The Anti-Masonic Party in the United States: 1826-1843" (1983). Political History. 13. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_political_history/13 The Antimasonic Party This page intentionally left blank The Antimasonic Party in the United States 1826-1843 WILLIAM PRESTON VAUGHN mE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Copyright © 1983 by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2009 The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress. ISBN 978-0-8131-9269-7 (pbk: acid-free paper) This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials. -

The Eighth Decade

1871-1880 The Eighth Decade Overview Batavia’s location on major railroad lines began to pay off in the eighth decade. The first manufacturing plant attracted by superior access to railroads, the Wiard Plow Company, moved to Batavia in 1876. More information about this company is in the following section titled, “Factories/industries.” The community continued to experience significant growth. According to the Federal census, by 1880 there were 4,845 residents (“Genesee County Information,” Richmond Memorial Library, online, accessed 3 January 2014). This was an increase of nearly 1,000 persons over a period of 10 years. NOTE: In this chapter, the two preceding ones, and the chapter that follows, alert readers may often notice citations for a source with a publication date that seemingly precedes the events for which the citations are given. That source is “William Seaver, A Historic Sketch of the Village of Batavia (Batavia, N.Y.: William Seaver & Son, 1849).” The dates at issue are those for 1850 and later. As mentioned in the introduction to this book, there are two publications in the local history collection of the Richmond Memorial Library with the above author, title, publisher, and date. However, one is actually the work of David Seaver, son of William Seaver, who was updating his late father’s work at the time of his own death in 1892. In order to distinguish between these two publications, the numerals “1” and “2” follow the author’s stated name in the citations. 1: Infrastructure In the eighth decade, the streets in Batavia were still unpaved.