The Power of Perception: the Failure of the Morgan Trials and the Formation of the Anti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diplomacy and the American Civil War: the Impact on Anglo- American Relations

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses, 2020-current The Graduate School 5-8-2020 Diplomacy and the American Civil War: The impact on Anglo- American relations Johnathan Seitz Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/masters202029 Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, Public History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Seitz, Johnathan, "Diplomacy and the American Civil War: The impact on Anglo-American relations" (2020). Masters Theses, 2020-current. 56. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/masters202029/56 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses, 2020-current by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Diplomacy and the American Civil War: The Impact on Anglo-American Relations Johnathan Bryant Seitz A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History May 2020 FACULTY COMMITTEE: Committee Chair: Dr. Steven Guerrier Committee Members/ Readers: Dr. David Dillard Dr. John Butt Table of Contents List of Figures..................................................................................................................iii Abstract............................................................................................................................iv Introduction.......................................................................................................................1 -

Martin Van Buren: the Greatest American President

SUBSCRIBE NOW AND RECEIVE CRISIS AND LEVIATHAN* FREE! “The Independent Review does not accept “The Independent Review is pronouncements of government officials nor the excellent.” conventional wisdom at face value.” —GARY BECKER, Noble Laureate —JOHN R. MACARTHUR, Publisher, Harper’s in Economic Sciences Subscribe to The Independent Review and receive a free book of your choice* such as the 25th Anniversary Edition of Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government, by Founding Editor Robert Higgs. This quarterly journal, guided by co-editors Christopher J. Coyne, and Michael C. Munger, and Robert M. Whaples offers leading-edge insights on today’s most critical issues in economics, healthcare, education, law, history, political science, philosophy, and sociology. Thought-provoking and educational, The Independent Review is blazing the way toward informed debate! Student? Educator? Journalist? Business or civic leader? Engaged citizen? This journal is for YOU! *Order today for more FREE book options Perfect for students or anyone on the go! The Independent Review is available on mobile devices or tablets: iOS devices, Amazon Kindle Fire, or Android through Magzter. INDEPENDENT INSTITUTE, 100 SWAN WAY, OAKLAND, CA 94621 • 800-927-8733 • [email protected] PROMO CODE IRA1703 Martin Van Buren The Greatest American President —————— ✦ —————— JEFFREY ROGERS HUMMEL resident Martin Van Buren does not usually receive high marks from histori- ans. Born of humble Dutch ancestry in December 1782 in the small, upstate PNew York village of Kinderhook, Van Buren gained admittance to the bar in 1803 without benefit of higher education. Building on a successful country legal practice, he became one of the Empire State’s most influential and prominent politi- cians while the state was surging ahead as the country’s wealthiest and most populous. -

1 Sumner, Charles. the Selected Letters of Charles Sumner. Edited

Sumner, Charles. The Selected Letters of Charles Sumner. Edited by Beverly Wilson Palmer. 2 vols. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1990. Vol. 2 Lawyers and politicians, 20 Lincoln, Seward, Sumner, Chicago convention nomination, 23-24 Law, barbarism of slavery, Lewis Tappan, 26 Crime Against Kansas speech, 29-30 Fugitive slave law, 31-32 Election, Lincoln, secession threats, 34 Seward, 37 Secession, 37ff Secession and possible civil war, 38-39 Thurlow Weed, Lincoln, Winfield Scott, 40-41 Scott, Seward, 42 John A. Andrew, no compromise, 43, 47-48 Fears compromise and surrender, 44 Massachusetts men need to stand firm, 46 Massachusetts, Buchanan, Crittenden compromise, 50-51 Personal liberty laws, 51-52 Fort Sumter, forts, 53 Virginia secession election, 54 New Mexico compromise, 55-57 Lincoln, 59 Lincoln and office seekers, 64 Seward influence, 64 Lincoln and war, 65 Northern unity, Lincoln, 69 John Lothrop Motley, 70-71 Congressional session, legislation, 71-72 Blockade, 73 Bull Run defeat, Lincoln, 74 Cameron and contrabands, 75 Lincoln, duty of emancipation, 76 William Howard Russell, Bull Run, 76-78 Slavery, Frémont, Lincoln, 79 Frémont, 80 Wendell Phillips, Sumner speech on slavery, 80 Slavery, English opinion, emancipation, Cameron, contraband order, 81-87 War, slavery, tariff, 82 Trent affair, Mason and Slidell, 85-94 Charles Stone, 95 Lieber, Stanton, Trent affair, 98 Stanton, 99 Lincoln, Chase, 100 Davis and Lincoln, 101 1 Andrew, McClellan, Lincoln, 103 Establishing territorial governments in rebel states, 103-8 Fugitive -

Whigs and Democrats Side-By-Side

The Campaign of 1840: William Henry Harrison and Tyler, Too — http://edsitement.neh.gov/view_lesson_plan.asp?id=553 Background for the Teacher After the debacle of the one-party presidential campaign of 1824, a new two-party system began to emerge. Strong public reaction to perceived corruption in the vote in the House of Representatives, as well as the popularity of Andrew Jackson, allowed Martin Van Buren to organize a Democratic Party that resurrected a Jeffersonian philosophy of minimalism in the federal government. This new party opposed the tendencies of National Republicans such as John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay to invest more power in the federal government. Van Buren built a political machine to support Jackson in the 1828 election. Van Buren’s skills helped give the Democrats a head start on modern-style campaigning and a clear advantage in organization. The Democrats defeated the National Republicans in 1828 and 1832. The Democrats maintained their hold on the presidency when they bested the Whigs—a union of former National Republicans, Antimasons, and some states’ rights advocates—in 1836. But a major economic depression in 1837 finally gave the Whigs their best chance to occupy the White House. They faced Andrew Jackson’s political organizer, vice-president, and handpicked successor, President Martin Van Buren, who was vying for a second term. By the time forces were readying themselves for the election of 1840, both Democrats and Whigs understood how to conduct effective campaigns. In an election that would turn out an astounding 80 percent of a greatly expanded electorate, the parties were learning to appeal to a wide range of voters in a variety of voting blocks, a vast change from the regionally based election of 1824. -

Abraham Lincoln Papers

Abraham Lincoln papers From Sydney H. Gay to [John G. Nicolay], September 17, 1864 New York, Sept. 17 1864 1 My Dear Sir— I write you at the suggestion of Mr. Wilkerson to state a fact or two which possibly you may make use of in the proper quarter. 1 Samuel Wilkeson was Washington bureau chief of the New York Tribune. Formerly an ally of Thurlow Weed, Wilkeson at this time was in the camp of Horace Greeley. 2 The recent changes in the N. Y. Custom House have been made at the demand of Thurlow Weed. 3 4 This is on the authority of a statement made by Mr. Nicolay to Surveyor Andrews & Genl. Busteed. Now Andrews refuses to resign, & if he is removed he will publish the facts substantiated by oath & 5 correspondence. It will go to the country that Mr. Lincoln removed from office a man of whom he thought so well that he promised to give him anything he asked hereafter, provided he would enable the President now to accede to the demands of the man who, outside of this state, is universally beleived to be the most infamous political scoundrel that ever cursed any country, & in the state is without influence with the party which he has publicly denounced & abandoned. Mr. Lincoln ought to know immediately that such is the attitude which he will occupy before the people if he persists in this matter. Andrews will defend himself, & I know, from a consultation with some of the leading men in the party here, to-day, that he will be upheld & justified in it, be the consequences what they may. -

Surname First JMA# Death Date Death Location Burial Location Photo

Surname First JMA# Death date Death location Burial Location Photo (MNU) Emily R45511 December 31, 1963 California? Los Molinos Cemetery, Los Molinos, Tehama County, California (MNU) Helen Louise M515211 April 24, 1969 Elmira, Chemung County, New York Woodlawn National Cemetery, Elmira, Chemung County, New York (MNU) Lillian Rose M51785 May 7, 2002 Las Vegas, Clark County, Nevada Southern Nevada Veterans Memorial Cemetery, Boulder City, Nevada (MNU) Lois L S3.10.211 July 11, 1962 Alhambra, Los Angeles County, California Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, Los Angeles County, California Ackerman Seymour Fred 51733 November 3, 1988 Whiting, Ocean County, New Jersey Cedar Lawn Cemetery, Paterson, Passaic County, New Jersey Ackerman Abraham L M5173 October 6, 1937 Paterson, Passaic County, New Jersey Cedar Lawn Cemetery, Paterson, Passaic County, New Jersey Ackley Alida M5136 November 5, 1907 Newport, Herkimer County, New York Newport Cemetery, Herkimer, Herkimer County, New York Adrian Rosa Louise M732 December 29, 1944 Los Angeles County, California Fairview Cemetery, Salida, Chaffee County, Colorado Alden Ann Eliza M3.11.1 June 9, 1925 Chicago, Cook County, Illinois Rose Hill Cemetery, Chicago, Cook County, Illinois Alexander Bernice E M7764 November 5, 1993 Whitehall, Pennsylvania Walton Town and Village Cemetery, Walton, Delaware County, New York Allaben Charles Moore 55321 April 12, 1963 Binghamton, Broome County, New York Vestal Hills Memorial Park, Vestal, Broome County, New York Yes Allaben Charles Smith 5532 December 12, 1917 Margaretville, -

Craft Masonry in Genesee & Wyoming County, New York

Craft Masonry in Genesee & Wyoming County, New York Compiled by R.’.W.’. Gary L. Heinmiller Director, Onondaga & Oswego Masonic Districts Historical Societies (OMDHS) www.omdhs.syracusemasons.com February 2010 Almost all of the land west of the Genesee River, including all of present day Wyoming County, was part of the Holland Land Purchase in 1793 and was sold through the Holland Land Company's office in Batavia, starting in 1801. Genesee County was created by a splitting of Ontario County in 1802. This was much larger than the present Genesee County, however. It was reduced in size in 1806 by creating Allegany County; again in 1808 by creating Cattaraugus, Chautauqua, and Niagara Counties. Niagara County at that time also included the present Erie County. In 1821, portions of Genesee County were combined with portions of Ontario County to create Livingston and Monroe Counties. Genesee County was further reduced in size in 1824 by creating Orleans County. Finally, in 1841, Wyoming County was created from Genesee County. Considering the history of Freemasonry in Genesee County one must keep in mind that through the years many of what originally appeared in Genesee County are now in one of other country which were later organized from it. Please refer to the notes below in red, which indicate such Lodges which were originally in Genesee County and would now be in another county. Lodge Numbers with an asterisk are presently active as of 2004, the most current Proceedings printed by the Grand Lodge of New York, as the compiling of this data. Lodges in blue are or were in Genesee County. -

1 Russell, William Howard. William Howard Russell's Civil War: Private

Russell, William Howard. William Howard Russell’s Civil War: Private Diary and Letters, 1861-1862. Edited by Martin Crawford. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1992. London, voyage to the United States, 3 South Carolina diplomat, secessionist, going home, war and possible blockade, 3-4 Lincoln, Olmsted book on slavery, 5 Americans refuse to pray for the royal family, 9 American women, 10 New York, 16ff Republicans, the South, Sumter, 17 Horatio Seymour, 17 Washington, 22ff Willard’s Hotel, 22 Seward, Lincoln, 22 Chaos opinions in New York, 23-25 George Bancroft, Horatio Seymour, Horace Greeley, August Belmont, James Gordon Bennett, 25 Dinner with Lincoln and cabinet, 28 Dinner, Chase, Douglas, Smith, Forsyth, 29 Seward, 31 Wants to know about expeditions to forts and pledges to Seward he could keep information secret, 32 Portsmouth and Norfolk, 36 Naval officer Goldsboro, 37 Charleston, Fort Sumter, 39 Report to Lord Lyons, Charleston, Beauregard, Moultrie, Sumter, 42-43 Seeks to have letters forward to Lord Lyons, 46 Complains of post office and his dispatches, 50 Montgomery, Wigfall, Jefferson Davis, Judah Benjamin, 52 Mobile, 53 Slaves, customs house, 55 Fort Pickens, Confederate determination, Bragg, 56-57 Wild Confederate soldiers, 58 Slidell, 62 Crime in New Orleans, jail, 63-64 New Orleans, traveling on Sunday, 65-66 Louisiana plantation, slaves, overseer, 67-70 Plantation, 71 Chicago Tribune, Harper’s Weekly, 74 Terrible war that will end in compromise, south is strong, 75-76 Winfield Scott vs. Jefferson Davis, 76-77 Deplores -

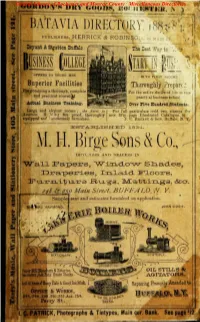

KM. H. Birge Sons & Co

Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Miscellaneous Directories S DRY GOOD^KQfjiEgTISB. \ PUBLISHERS, HERRICK & ROBINSO.s, ea Bryant & Styatton Buffalo The Lest 7,ray to \'.-: OPFEK8 TO YODNG MEN IS TO FIBST J6.COME Superior Facilities Thoroughly 'Prepare! For obtaining a thorough, complete For the active duties of life nt tins and practical course^kf practical business School. Actual Business Training. Over Five Hundred Students. Ij&rge and elegant rooms ; the finest in For full particulars send two stamps frr America. Bulging flre proof, thoroughly new fifty page Illustrated Catalogue to equipped and ; audsomely furnished. J. C. BRYANT & SON, Buffalo, N. Y. ESTABLISHED 183-i. KM. H. Birge Sons & Co., iMro.rriiRK AND DEALERS IN "Wall Papers, 'W±xi.clo-'w- Slxacies, Draperies, IxLla-xd- Floors, Fu.mitu.ra JEIXJL^S^ is/E&.'b'bi.-n.gs, &o. 248 QL 250 Main Street, BUFFALO, N. Y. sent and estiiiiates furuislied on application. I RI#.VRO HAMMOND, JOHN COON. f VI S Paper Mill Bleachers & Eotanes. OIL STILLS & SlP Smote Stacks AGITATORS. } Repairing Promptly Attendoi to. OFFICE & WORKS, 244.246.248.250.252.And.254. b To""'ro"o"o'o.B''|S- - Perry St. M I. p, PATRICK, Photographs & Tintypes, Main cor. Bank. See page '12 ; Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Miscellaneous Directories Rochester Public Library Bur Reference Book CcL Not For Circulation EAST MAIN THE LARGEST AND MOST RELIABLE WHOLESALE AND RETAIL Dry Goods & Carpet House In Western New York. Purchasing Offices in NEIV YORK, PARISH BERLIN ALL THE LATEST NOVELTIES IN BOTH LADIES' AND GENTLE- MEN'S GOODS CONSTANTLY ON HAND. -

Losing and Winning

Losing and Winning THE CRAFT AND SCIENCE OF POLITICAL CAMPAIGNS 1 There are three people that I want to acknowledge tonight because if it wasn’t for them, we would not be here . whenever the history is written about Alabama politics, remember those names, Giles Perkins,distribute Doug Turner and Joe Trippi. —DEMOCRATIC US SENATOR-ELECTor DOUG JONES CREDITED HIS UPSET VICTORY TO HIS CAMPAIGN MANAGERS IN A NATIONALLY TELEVISED VICTORY SPEECH ON THE EVENING OF DECEMBER 12, 2017.1 post, olitical campaigns are like new restaurants: Most of them will fail. Of the Pmore than 140 campaign managers we interviewed for this book, nearly all had lost elections—and many of them more than once. Even the most experienced and successful campaign manager can lose unexpectedly and even spectacularly. Consider the case of a campaign manager we will call “TW.” For three decades, he managed his candidate—his client and his best friend—rising from the New Yorkcopy, legislature, to the governor’s mansion, and on to the US Senate.2 Along the way, TW had worked for other candidates who were nominated for or won the presidency.3 TW’s skills as a campaign manager had earned him national renown and a very comfortable living. He was the undisputed American political notwizard behind the curtain. Now at the peak of his craft, TW was in Chicago at the Republican Party’s nominating convention. His client of thirty years was the front-runner to win the nomination. TW was so certain of the result that he had sent his candidate out of Do the country on a preconvention tour of European capitals. -

H. Doc. 108-222

Biographies 995 Relations, 1959-1973; elected as a Republican to the Eighty- ty in 1775; retired from public life in 1793; died in fifth and to the seven succeeding Congresses (January 3, Windham, Conn., May 13, 1807; interment in Windham 1957-January 3, 1973); was not a candidate for reelection Cemetery. in 1972 to the Ninety-third Congress; retired and resided Bibliography: Willingham, William F. Connecticut Revolutionary: in Elizabeth, N.J., where she died February 29, 1976; inter- Eliphalet Dyer. Hartford: American Revolutionary Bicentennial Commission ment in St. Gertrude’s Cemetery, Colonia, N.J. of Connecticut, 1977. DYAL, Kenneth Warren, a Representative from Cali- DYER, Leonidas Carstarphen (nephew of David Patter- fornia; born in Bisbee, Cochise County, Ariz., July 9, 1910; son Dyer), a Representative from Missouri; born near attended the public schools of San Bernardino and Colton, Warrenton, Warren County, Mo., June 11, 1871; attended Calif.; moved to San Bernardino, Calif., in 1917; secretary the common schools, Central Wesleyan College, Warrenton, to San Bernardino, County Board of Supervisors, 1941-1943; Mo., and Washington University, St. Louis, Mo.; studied served as a lieutenant commander in the United States law; was admitted to the bar in 1893 and commenced prac- Naval Reserve, 1943-1946; postmaster of San Bernardino, tice in St. Louis, Mo.; served in the Spanish-American War; 1947-1954; insurance company executive, 1954-1961; mem- was a member of the staff of Governor Hadley of Missouri, ber of board of directors -

Chapter Twenty-Five “This Damned Old House” the Lincoln Family In

Chapter Twenty-five “This Damned Old House” The Lincoln Family in the Executive Mansion During the Civil War, the atmosphere in the White House was usually sober, for as John Hay recalled, it “was an epoch, if not of gloom, at least of a seriousness too intense to leave room for much mirth.”1 The death of Lincoln’s favorite son and the misbehavior of the First Lady significantly intensified that mood. THE WHITE HOUSE The White House failed to impress Lincoln’s other secretaries, who disparaged its “threadbare appearance” and referred to it as “a dirty rickety concern.”2 A British journalist thought it beautiful in the moonlight, “when its snowy walls stand out in contrast to the night, deep blue skies, but not otherwise.”3 The Rev. Dr. Theodore L. Cuyler asserted that the “shockingly careless appearance of the White House proved that whatever may have been Mrs. Lincoln’s other good qualities, she hadn’t earned the compliment which the Yankee farmer paid to his wife when he said: ‘Ef my wife haint got an ear fer music, she’s got an eye for dirt.’”4 The north side of the Executive 1 John Hay, “Life in the White House in the Time of Lincoln,” in Michael Burlingame, ed., At Lincoln’s Side: John Hay’s Civil War Correspondence and Selected Writings (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2000), 134. 2 William O. Stoddard, Inside the White House in War Times: Memoirs and Reports of Lincoln’s Secretary ed. Michael Burlingame (1880; Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000), 41; Helen Nicolay, Lincoln’s Secretary: A Biography of John G.