LEGAL NEEDS دراسة حول االحتياجات القانونية in East Jerusalem في القدس الشرقية

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Effect of New Media On

SATELLITES, CITIZENS AND THE INTERNET: THE EFFECT OF NEW MEDIA ON THE POLICIES OF THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY By Creede Newton Submitted to Central European University Department of Public Policy In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Public Policy Supervisor: Miklós Haraszti CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2014 I, the undersigned……Creede Newton…………..……………….hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. To the best of my knowledge this thesis contains no material previously published by any other person except where the due acknowledgment has been made. This thesis contains no material which has been accepted as part of the requirements of any other academic degree or non-degree program, in English or in any other language. This is a true copy of the thesis, including final revisions. Date: …………9 June 2014……………………………………………. Name (printed letters): …....Creede Newton.............………………………. Signature: ……… ………Creede Newton……………………………......... CEU eTD Collection Abstract The effect of New Media in the wave of protests that swept the Arab World in 2011-2012 has generated a large body of scholarly work due to the widespread calls for democratization in a region that had been entirely under the control of authoritarian leaders for decades. However, in the wake of these protest there has been little research into what effect New Media had those countries which did not experience regime change. This paper will examine the impact of New Media on the policies of the Palestinian Authority. It will show that New Media has the potential for an increase in democratic characteristics, i.e. steps towards a more transparent government that listens to the people, even in the absence of successful democratization. -

The Politics of Israel/Palestine Thursdays 2:35-5:25 Course Location: CB 3208 (Please Confirm on Carleton Central)

PSCI 5915-W Winter 2019 Special Topics: The Politics of Israel/Palestine Thursdays 2:35-5:25 Course Location: CB 3208 (Please confirm on Carleton Central) Department of Political Science Carleton University Prof. Mira Sucharov Office: C678 Loeb [email protected] Office Hours: Weds 2:30-3:55 or by appointment. (Please do not use my voice mail. Email is the best way to reach me. [email protected]) Course Description: This course examines the politics of Israel/Palestine. It would be customary in IR and political science when studying one country or region to consider it a “case” of something. But as we will see, the politics around Israel-Palestine is in large part animated by the contestation over such classification. Is it a case of protracted conflict? A case of colonial oppression? A case of human rights violations? A case of competing nationalisms? The course will examine these competing (though not necessarily mutually-exclusive) frameworks. The course proceeds both chronologically and conceptually/thematically. Those without a basic knowledge of the case might wish to purchase a textbook to read early on. (Suggestions: those by Dowty, Smith, and Caplan.) In addition, to further explore op-ed writing (and social media engagement, especially around sensitive topics), you may want to consult my book on the topic (optional), which should be out in mid-to-late January. Mira Sucharov, Public Influence: A Guide to Op-Ed Writing and Social Media Engagement (University of Toronto Press, 2019). Books: Sucharov, The International Self (available at the Carleton bookstore). Tolan, Children of the Stone: The Power of Music in a Hard Land (the book is optional: I have included excerpts, below). -

In Search of a Viable Option Evaluating Outcomes to the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

Policy Report In Search of a Viable Option Evaluating Outcomes to the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict A report by Dr. Shira Efron and Evan Gottesman, with a foreword by Ambassador Daniel B. Shapiro Is the two-state solution still possible? Are other frameworks better or more feasible than two states? This study seeks to answer these questions through a candid and rigorous analysis. Is there another viable outcome? While the two-state model deserves to be debated on its merits, and certainly on its viability, pronouncements of this formula’s death raise the question: if not two states, then what? About the Study The two-state solution has been widely criticized from the right and the left as an idea whose time has passed and been overtaken by facts on the ground. As a result, many other models for the Israeli-Palestinian conflict have been advanced, from one-state formulas to confederation outcomes to maintaining the status quo indefinitely. How do these proposals for the Israeli-Palestinian conflict — including the recently released Trump plan — measure up against key criteria, like keeping Israel Jewish and democratic, providing security, and ensuring feasibility? Is there a model that fits the needs of both parties while being realistic in practice? This comprehensive study of potential outcomes for the Israeli-Palestinian conflict assesses the strengths and weaknesses of different plans, and trains a critical eye on whether a two-state solution is still possible, concluding that despite the heavy lift it will take to implement, a two-state outcome is not only possible but the only implementable plan that maintains Israel as Jewish and democratic. -

Palestine's Ongoing Nakba

al majdal DoubleDouble IssueIssue No.No. 39/4039/40 BADIL Resource Center Resource BADIL quarterly magazine of (Autumn(Autumn 20082008 / WinterWinter 2009)2009) BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights jjabaliyaabaliya a wwomanoman wearswears a bellbell carriescarries a light callscalls searchessearches by Suheir Hammad through madness of deir yessin calls for rafah for bread orange peel under nails blue glass under feet gathers children in zeitoun sitting with dead mothers she unearths tunnels and buries sun onto trauma a score and a day rings a bell she is dizzy more than yesterday less than tomorrow a zig zag back dawaiyma back humming suba back shatilla back ramleh back jenin back il khalil back il quds Palestine's all of it all underground in ancestral chests she rings a bell promising something she can’t see faith is that faith is this all over the land under the belly of wind she perfumed the love of a burning sea Ongoing concentrating refugee camp crescent targeted red NNakbaakba a girl’s charred cold face dog eaten body angels rounded into lock down shelled injured shock weapons for advancing armies clearing forests sprayed onto a city o sage tree human skin contact explosion these are our children Double Issue No. 39/40 (Autumn 2008 / Winter 2009) Winter / 2008 (Autumn 39/40 No. Issue Double she chimes through nablus back yaffa backs shot under spotlight phosphorous murdered libeled public relations public quarterly magazine quarterly relation a bell fired in jericho rings through blasted windows a woman Autumn 2008 / Winter 2009 1 carries bones in bags under eyes disbelieving becoming al-Majdal numb dumbed by numbers front and back gaza onto gaza JJaffaaffa 1948....Gaza1948....Gaza 20082008 for gaza am sorry gaza am sorry she sings for the whole powerless world her notes pitch perfect the bell a death toll BADIL takes a rights-based approach to the Palestinian refugee issue through research, advocacy, and support of community al-Majdal is a quarterly magazine of participation in the search for durable solutions. -

Of Palestine’S Ongoing Nakba

Badil 2011 Desk-Calendar - Available in English and Arabic. This year’s calendar is titled “Rights in Principle – Rights in Practice: 20 years of processing peace”. It includes photos and information on the root causes of ongoing forced displacement and dispossession of Palestinians, an assessment of 20 years of failed peace diplomacy and civil society-led efforts to hold Israel accountable for its systematic abuse of the rights of the Palestinian people. Relevant historic dates and events are marked for each month of the year, as well as information about some of the specific aspects of Palestine’s ongoing Nakba. BADIL Working Paper No.11 Issue No. 45 (Winter 2010) Principles & Mechanisms to Hold Business Accountable for al majdal quarterly magazine of Human Rights Abuses - Potential Avenues to Challenge Corporate Involvement in Israel’s Oppression of the Palestinian People - Available BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights in English and Arabic, 70 pages. By Yasmine Gado Available! Now The mechanisms available within the existing legal and economic framework to advance corporate accountability for human rights abuses, and for their conduct in other areas of social concern, generally fall into three categories: (1) domestic law: regulation and litigation under state domestic legal systems; (2) international law: binding international law governing corporate complicity in international crimes and non-binding international norms on the issue of business and human rights; and (3) market forces: socially responsible investment funds, shareholder activism, consumer boycotts, etc. This article summarizes the latest developments in each of these areas. Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons 2008-2009 - Available in English and Arabic, 215 pages. -

THE POLITICAL MAPPING of PALESTINE Linda Elizabeth

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository THE POLITICAL MAPPING OF PALESTINE Linda Elizabeth Quiquivix A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Geography Chapel Hill 2012 Approved by: Altha J. Cravey Banu Gökariksel John Pickles Alvaro Reyes Sara Smith Jonathan Weiler ABSTRACT LINDA QUIQUIVIX: The Political Mapping of Palestine (Under the direction of Altha J. Cravey) Debates on the Israel-Palestinian conflict abound. Insofar as these discussions focus on what peace between Israelis and Palestinians might look like, they often resort to what the map should look like. Motivated by concerns over how cartographic practices have become uncritically adopted by the Palestinian movement since the advent of the “peace process,” this dissertation critically examines the map’s role in producing the conflict, in hindering a liberatory politics, and in maintaining the current impasse. This study is largely structured as a genealogy of Palestine’s maps from the nineteenth- century to the present—an array of mappings produced by a multitude of actors: colonial, religious, nationalist, statist, diasporic and revolutionary, both from above and from below. These historical-political excavations are theoretically grounded within the literature on critical cartography, the production of space, and feminist political geography. They are examined empirically through archival research, ethnographic methods, and discourse analysis. This study’s theoretical intervention highlights the map’s production of Palestine as a space of ownership and control. -

Stanford Stanford

Stanford_Covers:1 tracking migration.fall.04 10/12/07 10:08 AM Page 1 Carol Lam ’85 on Life After the DOJ Stanford University Non-profit ReputationDefender: A 1L Makes Time for a Startup Stanford Law School Organization Crown Quadrangle U.S. Postage Paid 559 Nathan Abbott Way Palo Alto, CA STANFORD Stanford, CA 94305-8610 Permit No. 28 STANFORD LAWYER FALL 2007 ISSUE 77 77 77 LAWYER FALL 2007 ISSUE FALL FALL 2007 ISSUE FALL AT THE TIPPING POINT TODAY’S CHANGING BUSINESS OF LAW Stanford_Covers:1 tracking migration.fall.04 10/12/07 10:08 AM Page 2 gatheringsSTANFORD From the Dean LAWYER BY LARRY KRAMER ISSUE 77/VOL. 42/NO. 1 Richard E. Lang Professor of Law and Dean MOST DEANS (INCLUDING THIS ONE) USE THESE INTRODUCTORY LETTERS TO Editor PRIME READERS FOR ACHIEVEMENTS CELEBRATED IN THE PAGES THAT FOLLOW. kudos SHARON DRISCOLL The object is less to challenge than to instill a sense of anticipation and pride. This letter is [email protected] different. The focus of this issue is the state of our profession. And that is a worrisome topic. • I Associate Dean for Communications to and Public Relations have occasionally remarked, though only in small settings before today, that the state of the legal MICHAEL ARRINGTON ’95, founder of TechCrunch, appeared as 22 on Business 2.0’s list, SABRINA JOHNSON profession brings to mind Rome, circa A.D. 300. On the surface, it looks grander and more “The 50 Who Matter Now,” printed in July. [email protected] magnificent than ever, but the foundation may be about to collapse. -

PETER BOUCKAERT '97 at Stanford Law School

anf yer Ifyou have been appointed to the bench recently, we want to know about it! n October 1999, Stanford Law School unveiled its Judiciary Atrium in an effort to pay tribute to the more than 300 alumni I who had served or were serving on the bench. The display is housed in Crown Quadrangle, on the first floor of EI.R. Hall, the Law School's classroom building, and is available for students, faculty, alumni, and visitors to view at any time. The atrium is updated at the end of each summer to reflect new appointments to state supreme and superior courts, federal district and appellate courts, international and tribal courts, and the United States Supreme Court. If you, or a fellow alumnus/a, have been appointed to any of these courts and do not appear in the atrium, please contact Karen Lindblom, Assistant Director of Development, Stewardship, at 650/723-3085 for information about how to be included in this permanent recognition piece. SUMMER 2002 / ISSUE 63 -,0 ents Features 12 WOMEN, LEADERSHIP, AND STANFORD LAW SCHOOL 13 The women who graduate from Stanford Law School go on to reach the pinnacles of their profession. A conference and celebration at the Law School considered steps that can be taken to help others follow this path, 16 CHARMING THE LAW SCHOOL Sheila Spaeth, the widow of the late Dean Carl Spaeth, did not write any scholarly papers or lecture to a class ofsrudents, But her warmth and kindness endeared her to a generation ofStanford Law graduates and helped turn the School into a powerhouse. -

The Fallout of the 2015 Israeli Elections. Interview with Diana Buttu

PAL PAPERS April 2015 The Fallout of the 2015 Israeli Elections: Diana Buttu Reflects on the Impact of the Elections on the Question of Palestine and Steps on how to Proceed Forward Chris Whitman: My first question is what are Zionist Camp, and say “ok they believe in SOME your overall impressions of the elections? Palestinian rights, but not full rights,” you are then looking at around 100 seats, out of 120. Diana Buttu: I am not at all surprised by how So that leaves a spectrum of 20 seats, that’s all, things worked out. I think the only thing that 1/6 of the population who believes that there surprised me were the initial polls that were should be equal rights for Palestinians...whether indicating that the Zionist Camp was doing better that is in the form of two states, or the form of than they ended up doing. This is also no surprise equality, this is the landscape that we are looking because, it is not just a question of whether at now. This isn’t some scenario where Likud just Likud managed to garner the highest number of parachuted in from nowhere. There has been a seats but it is important to look at the spectrum very steady march and shift to the right over the of where the votes actually went...who got seats course of the past 15-20 years, maybe more, and and who didn’t get seats, to get a perspective again not just a shift to the right, but the extreme of what Israel as a country is now looking like. -

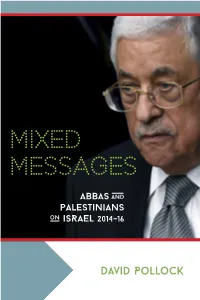

Mixed Messages

MIXED MESSAGES ABBAS and palestinians on isRael 2014–16 David Pollock David Pollock MIXED MESSAGES ABBAS and palestinians on isRael 2014–16 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY WWW.WASHINGTONINSTITUTE.ORG The opinions expressed in this Policy Focus are those of the author and not necessarily those of The Washington Institute, its Board of Trustees, or its Board of Advisors. Policy Focus 144, April 2016 All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ©2016 by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy The Washington Institute for Near East Policy 1111 19th Street NW, Suite 500 Washington, DC 20036 Design: 1000colors Photo: Mahmoud Abbas, February 2016 (REUTERS/Franck Robichon/Pool) CONTENTS Acknowledgments | v Introduction | vii 1: Themes in PA Messaging | 1 2: PA Messaging: Chronology | 23 3: PA Messaging and Palestinian Public Opinion, 2014–15 | 43 4: Policy Implications | 65 Notes | 71 About the Author | 82 ILLUSTRATIONS FIGS. 1–7: Internet Examples of Mixed Messaging | vi FIG. 8: Poll Response on Palestinian National Goal | 51 FIG. 9: Poll Response on Maintaining a Ceasefire | 53 FIG. 10: Poll Response on Top Priorities | 57 FIG. 11: Poll Response on Negotiating a Two-State Solution | 59 FIG. 12: Poll Response on Palestinian Ability to Work in Israel | 60 FIG. 13: Poll Response on “Two States for Two Peoples” | 63 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude for outstanding research sup- port from a great team of young scholars, in particular Catherine Cleve- land, Gavi Barnhard, and Adam Rasgon. -

DISCUSSION PAPER Formalising Apartheid

DISCUSSION PAPER Formalising Apartheid: Israel’s Proposed Annexation of the West Bank Elif Zaim DISCUSSION PAPER Formalising Apartheid: Israel’s Proposed Annexation of the West Bank Elif Zaim Formalising Apartheid: Israel’s Proposed Annexation of the West Bank © TRT WORLD RESEARCH CENTRE ALL RIGHTS RESERVED WRITTEN BY Elif Zaim PUBLISHER TRT WORLD RESEARCH CENTRE August 2020 TRT WORLD İSTANBUL AHMET ADNAN SAYGUN STREET NO:83 34347 ULUS, BEŞİKTAŞ İSTANBUL / TURKEY TRT WORLD LONDON PORTLAND HOUSE 4 GREAT PORTLAND STREET NO:4 LONDON / UNITED KINGDOM TRT WORLD WASHINGTON D.C. 1819 L STREET NW SUITE 700 20036 WASHINGTON DC www.trtworld.com researchcentre.trtworld.com The opinions expressed in this discussion paper represent the views of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the TRT World Research Centre. 4 Formalising Apartheid: Israel’s Proposed Annexation of the West Bank Introduction enjamin Netanyahu began For many Palestinians who have felt a sense of his fifth term in office as the abandonment by Arab states, formal annexa- longest-serving Prime Min- tion means an end to their remaining hopes for ister this year after three self-determination and the establishment of an inconclusive elections. His independent state. While there are arguments most widely debated elec- that the move would finally bury the two-state Btion pledge has been the annexation of the il- solution, which envisages an independent Pal- legal Israeli settlements in the occupied West estinian state alongside Israel on pre-1967 bor- Bank. While July 1st was supposed to be the ders with a shared capital of Jerusalem, calls beginning of the process, the date has passed are growing to create one democratic state with without any action. -

Beyond Chutzpah: on the Misuse of Anti-Semitism and the Abuse of History (2005)

BEYOND CHUTZPAH Beyond Chutzpah On the Misuse of Anti-Semitism and the Abuse of History UPDATED EDITION WITH A NEW PREFACE NORMAN G. FINKELSTEIN UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles University of California Press, one of the most distin- guished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California © 2005, 2008 by Norman G. Finkelstein First Paperback edition, 2008 isbn 978-0-520-24989-9 The Library of Congress has cataloged the earlier edition of this book as follows: Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Finkelstein, Norman G. Beyond chutzpah : on the misuse of anti-semitism and the abuse of history / Norman G. Finkelstein. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn: 0-520-24598-9 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Arab-Israeli conflict. 2. Palestinian Arabs— Crimes against. 3. Dershowitz, Alan M. Case for Israel. 4. Zionism. 5. Human rights—Palestine. I. Title. ds119.7.f544 2005 323.1192'7405694—dc22 2005000117 Manufactured in the United States of America 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 10987654321 This book is printed on New Leaf EcoBook 50, a 100% recycled fiber of which 50% is de-inked post- consumer waste, processed chlorine-free. EcoBook 50 is acid-free and meets the minimum requirements of ansi/astm d5634-01 (Permanence of Paper).