Jim Story : Former Disney Feature Animation Story Artist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPA : Redesigning Animation

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. UPA : redesigning animation Bottini, Cinzia 2016 Bottini, C. (2016). UPA : redesigning animation. Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/69065 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/69065 Downloaded on 05 Oct 2021 20:18:45 SGT UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI SCHOOL OF ART, DESIGN AND MEDIA 2016 UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI School of Art, Design and Media A thesis submitted to the Nanyang Technological University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.” Paul Klee, “Creative Credo” Acknowledgments When I started my doctoral studies, I could never have imagined what a formative learning experience it would be, both professionally and personally. I owe many people a debt of gratitude for all their help throughout this long journey. I deeply thank my supervisor, Professor Heitor Capuzzo; my cosupervisor, Giannalberto Bendazzi; and Professor Vibeke Sorensen, chair of the School of Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore for showing sincere compassion and offering unwavering moral support during a personally difficult stage of this Ph.D. I am also grateful for all their suggestions, critiques and observations that guided me in this research project, as well as their dedication and patience. My gratitude goes to Tee Bosustow, who graciously -

Bruno Bozzetto

26/5/2015 www.unibg.it/static_content/presentazioneateneo/lhbozzetto.htm#conferimento Bruno Bozzetto laurea specialistica honoris causa in Teoria, tecniche e gestione delle arti e dello spettacolo a.a. 2006/2007 lectio magistralis conferimento elogio Bruno Bozzetto Lectio Magistralis Magnifico Rettore, Professori, Autorità, amici e studenti, non credo d'essere molto originale dicendo di sentirmi emozionato, e questo non solo per il grande onore che oggi mi viene reso, ma perché il mio mezzo di comunicazione sono sempre stati i disegni, e ora devo invece usare le parole... Un mezzo che, nel mio caso personale, non esiterei a definire decisamente "improprio". Proprio per questo, ben conoscendo i miei limiti, ho deciso di scrivere le mie parole e di farmi sostenere con la proiezione di qualche film. Prima di iniziare desidero però ringraziare sentitamente il Magnifico Rettore, professor Alberto Castoldi, e tutti coloro che mi hanno proposto per questa onorificenza, che rappresenta per me, per la mia professione e per tutti i collaboratori uno dei momenti più gratificanti. Desidero innanzitutto cogliere questa bella opportunità per ricordare pubblicamente la figura di mio padre Umberto, una persona straordinaria, senza il cui aiuto morale e finanziario non avrei mai potuto intraprendere questa attività. Nella vita la fortuna gioca sempre un ruolo fondamentale, e probabilmente tutti noi, se non ci fossimo trovati nel luogo giusto al momento giusto, avremmo scelto altre carriere ed altre direzioni. La mia grande fortuna è stata quella di nascere in una splendida famiglia com'era la mia, con un padre eccezionale, creativo, dinamico e soprattutto lungimirante, che ha sempre rappresentato per me, oggi come allora, una fonte inesauribile d'ispirazione, da cui ho attinto idee, spirito critico e soprattutto il coraggio di intraprendere una carriera così particolare ed a quei tempi così poco promettente. -

Guide to the Mahan Collection of American Humor and Cartoon Art, 1838-2017

Guide to the Mahan collection of American humor and cartoon art, 1838-2017 Descriptive Summary Title : Mahan collection of American humor and cartoon art Creator: Mahan, Charles S. (1938 -) Dates : 1838-2005 ID Number : M49 Size: 72 Boxes Language(s): English Repository: Special Collections University of South Florida Libraries 4202 East Fowler Ave., LIB122 Tampa, Florida 33620 Phone: 813-974-2731 - Fax: 813-396-9006 Contact Special Collections Administrative Summary Provenance: Mahan, Charles S., 1938 - Acquisition Information: Donation. Access Conditions: None. The contents of this collection may be subject to copyright. Visit the United States Copyright Office's website at http://www.copyright.gov/for more information. Preferred Citation: Mahan Collection of American Humor and Cartoon Art, Special Collections Department, Tampa Library, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida. Biographical Note Charles S. Mahan, M.D., is Professor Emeritus, College of Public Health and the Lawton and Rhea Chiles Center for Healthy Mothers and Babies. Mahan received his MD from Northwestern University and worked for the University of Florida and the North Central Florida Maternal and Infant Care Program before joining the University of South Florida as Dean of the College of Public Health (1995-2002). University of South Florida Tampa Library. (2006). Special collections establishes the Dr. Charles Mahan Collection of American Humor and Cartoon Art. University of South Florida Library Links, 10(3), 2-3. Scope Note In addition to Disney animation catalogs, illustrations, lithographs, cels, posters, calendars, newspapers, LPs and sheet music, the Mahan Collection of American Humor and Cartoon Art includes numerous non-Disney and political illustrations that depict American humor and cartoon art. -

Hayao Miyazaki: Exploring the Early Work of Japan’S Greatest Animator

Greenberg, Raz. "Bringing It All Together: Studio Ghibli." Hayao Miyazaki: Exploring the Early Work of Japan’s Greatest Animator. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018. 107– 126. Animation: Key Films/Filmmakers. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 1 Oct. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501335976.ch-005>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 1 October 2021, 09:34 UTC. Copyright © Raz Greenberg 2018. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. C h a p t e r 5 B RINGING IT A LL T OGETHER : S TUDIO G HIBLI Several months aft er the Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind manga started its run in 1982, Miyazaki was hired, along with his colleagues Isao Takahata, Yasuo Ō tsuka, and Yoshifumi Kond ō , to take part in the production of Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland . Th e ambitious American/Japanese coproduction adapted the classic comic strip by cartoonist and animation pioneer Winsor McCay about a boy who, each night, goes on a strange adventure in his dreams. McCay’s work had many fans on both sides of the Pacifi c: in fact, the project was initiated by Japanese producer Yutaka Fujioka, the president of Tokyo Movie Shinsha, the studio that previously employed Miyazaki and Takahata on Moomins , the Panda! Go Panda! fi lms, and the Lupin productions. Many other notable fi gures have been involved with diff erent stages of the production including Jean Giraud, renowned science fi ction author Ray Bradbury, and screenwriter Chris Columbus (future director of the early Harry Potter fi lms). -

OFF-RAMP Saturday 12-1 P.M.; Sunda with J Support All the Great Programming on KPCC, Including Off-Ramp

OFF-RAMP Saturday 12-1 p.m.; Sunda with J Support all the great programming on KPCC, including Off-Ramp. SHARE THIS: Facebook (16) Twitter (8) Google+ Email Print 1 Comments Add your comments Listen Now [5 min 17 sec] • Download Off-Ramp Charles Solomon reviews The Animation Show of Shows Off Ramp animation critic Charles Solomon | Off-Ramp | January 9th, 2013, 10:33am Frédéric Back Still from "The Man Who Planted Trees" (1987) by Frédéric Back. Almost since the art form began, there's been a split between animation as a studio product and animation as a vehicle for individual expression. The enormous succe features and TV shows has kept the work of the major animation studios uppermost in the minds of American audiences recently. But beginning with the pioneer cartoonist and filmmaker Winsor McCay - - back in the early 1900's -- independent artists have treated animation as an art as personal, flexible and immediate as painting or sculpture. Their work is an entirely different vision of what an animated film can be, as the new DVD box set The Animation Show of Shows richly proves. Volume 3 just came out. The artists who create these films may teach or support themselves with other jobs or work at a government-sponsored body, like the National Film Board of Canada. Some are students, and some are professionals pursuing their visions in their spare time. They're united by a commitment to the art of animation. M any of the films in Show of Shows use techniques that are too impractical or personal for large scale production. -

Animation for Extremely Smart Grownups of All Ages

Animation for Extremely Smart Grownups of All Ages Prof. Russell Merritt Summer 2018 [email protected] Thursdays 1-3 University Hall Room 150 Week 1 [June 7]: The Language of Animation, from Slash and Tear to Chroma Keys Home Screening Ben Sharpsteen and Hamilton Luske, Pinocchio (Disney/ R.K.O. Radio, 1940) 90 mins. Chuck Jones, Duck Amuck (WB, 1953) 7 mins. Readings: OLLI Animation Glossary; Thomas & Johnston; Paul Week 2 [June 14]: How to Make a Cartoon Look Good: Art Nouveau, Art Deco, and Surrealism, and Cartoon Modern Home Screening Lotte Reiniger, Die Abenteuer des Prinzen Achmed [The Adventures of Prince Achmed] (Comenius Film, 1926). 65 mins/ 80 mins. Anthony Gross & Hector Hoppin Joie de Vivre (Paris, 1934) 9 mins. Len Lye, Rainbow Dance (GPO Film Unit for GPO Savings Bank, 1936) 4 mins Tex Avery, Paging Miss Glory (WB, 1936) 7 mins. Robert Cannon, Gerald McBoing Boing (UPA, 1951) 8 mins. Reading: “Magic Horse;” “Fisherman;” Wollen; Lye; Kepes Week 3 [June 21]: Political Parables and Animated Notebooks Home Viewings Norman McLaren, Neighbours (NFBC, 1952) Montreal, 8 mins. Jiři Trnka, The Hand [Ruka] (Krátký Film, 1965) Prague, 18 mins. Frédéric Back, Crac! (Production Societé Radio-Canada, 1981) Ville de Québec, 14 mins. Piotr Dumala, Freedom of the Leg ( Se-Ma-For, 1989) Łódź 10 mins. Jan Švankmajer, Rakvickárna [The Coffin House/ Punch and Judy] (Krátký Film, 1966) Prague, 10 mins. Yuri Norstein, Tale of Tales (Russia: Soyuzmultfilm, 1979) 30 mins. Readings: Russett & Starr; Lawrence; Kitson Week 4 [June 28]: Wired Animation Home Screening Henry Selick, Coraline (Laika/ Pandemonimum, 2009) 1 1 hr 40 mins [and, if you have time] Suzie Templeton, Peter and the Wolf (Poland/ U.K., 2008) 30 mins. -

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs: New Perspectives on Production, Reception, Legacy

Holliday, Christopher, and Chris Pallant. "Introduction: Into the burning coals." Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs: New Perspectives on Production, Reception, Legacy. Ed. Chris Pallant and Christopher Holliday. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2021. 1–22. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 30 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501351198-005>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 30 September 2021, 04:44 UTC. Copyright © Chris Pallant and Christopher Holliday 2021. You may share this work for non- commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 1 Introduction: Into the burning coals Christopher Holliday and Chris Pallant The wicked woman uttered a curse, and she became so frightened, so frightened, that she did not know what to do. At fi rst she did not want to go to the wedding, but she found no peace. She had to go and see the young queen. When she arrived she recognized Snow-White, and terrorized, she could only stand there without moving. Then they put a pair of iron shoes into burning coals. They were brought forth with tongs and placed before her. She was forced to step into the red-hot shoes and dance until she fell down dead. 1 To undertake a scholarly project on the Wonderful World of Disney, in particular one focused on the historical, cultural and artistic signifi cance of its celebrated cel-animated feature fi lm Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (David Hand, 1937), is an endeavour that often feels like jumping headlong ‘into burning coals’. -

22 VII. the New Golden Age Then Something Wonderful Happened. Just When Everything Was Looking As Grim As It Could for the Art O

VII. The New Golden Age Then something wonderful happened. Just when everything was looking as grim as it could for the art of animation, technology came to the rescue. Here was an art form born only because technology made it possible, almost died when the human costs in time and effort became too high, and now was rescued by technology again. The computer age saved animation. Since computers first came on the scene in the 50s, there have been people who have tried to create machinery and programs to make animation faster, easier and cheaper to both make and distribute. From machines like copiers and scanners, to computers that can draw and render, to the distribution of animation by cable, Internet, phones, tablets and video games - as one character says, “To infinity and beyond” - animation has been totally reborn. As the old animators of the Golden Age were dying off, the new technologies created a huge demand for the old craft. Fortunately, many of the old men were able to pass on their skills to a younger generation, which has helped the quality of today's animation meet and exceed the animation of the Golden Age. In 1985, Girard and Maciejewski at OSU publish a paper describing the use of inverse kinematics and dynamics for animation.! The first live-action film to feature a complete computer-animated character is released, "YOUNG SHERLOCK HOLMES."! Ken Perlin at NYU publishes a paper on noise functions for textures. He later applied this technique to add realism to character animations. In 1986, "A GREEK TRAGEDY" wins the Academy Award. -

Frederick S. Litten a Mixed Picture Drawn Animation/Live Action Hybrids

Frederick S. Litten A Mixed Picture drawn animation/live action hybrids worldwide from the 1960s to the 1980s In 1977, Bruno Edera suggested that full-length animated films had entered “a new „Golden Age‟” (Edera, 93), with directors working in “new modes of cinema”, including what he called “films in mixed media” (ibid., 14), otherwise often described as “mixed” or “hybrid” animation. Combining animation and live action is about as old as animation itself, or to be more pre- cise, as the perception of animation as something distinctly separate from live action (Crafton, 9). It can be found, to give just two early examples, in Sculpteur Moderne (France, 1908) by Segundo de Chomón, where live action and clay animation are presented, or in Winsor McCay‟s Little Nemo (USA, 1911), which combined live action and drawn animation. Yet, as a genre, hybrid animation has not been studied much from a historical point of view. In his recent book Animating Space, for example, J. P. Telotte is concerned with hybrid animation, but mostly from the United States. Moreover, the period between two of the acknowledged masterpieces and commercial successes of their kind – Mary Poppins (USA, 1964) and Who Framed Roger Rabbit (USA, 1988) – is covered in less than two lines (Te- lotte, 180). This paper will, in contrast to Telotte, focus on feature films (60 minutes and longer) and TV series combining drawn animation and live action which were produced in various coun- tries from the 1960s to the 1980s.1 It will propose first a descriptive classification scheme us- ing examples from the United States and Great Britain, assuming these are known best and are easiest to access internationally. -

Animation Fandom in North America and East Asia from 1906–2010 By

Animating Transcultural Communities: Animation Fandom in North America and East Asia from 1906–2010 By Sandra Annett A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of English, Film, and Theatre University of Manitoba Winnipeg © 2011 Sandra Annett Abstract This dissertation examines the role that animation plays in the formation of transcultural fan communities. A ―transcultural fan community‖ is defined as a group in which members from many national, cultural, and ethnic backgrounds find a sense of connection across difference, engaging with each other through a mutual interest in animation while negotiating the frictions that result from their differing social and historical contexts. The transcultural model acts as an intervention into polarized academic discourses on media globalization which frame animation as either structural neo-imperial domination or as a wellspring of active, resistant readings. Rather than focusing on top-down oppression or bottom-up resistance, this dissertation demonstrates that it is in the intersections and conflicts between different uses of texts that transcultural fan communities are born. The methodologies of this dissertations are drawn from film/media studies, cultural studies, and ethnography. The first two parts employ textual close reading and historical research to show how film animation in the early twentieth century (mainly works by the Fleischer Brothers, Ōfuji Noburō, Walt Disney, and Seo Mitsuyo) and television animation in the late twentieth century (such as The Jetsons, Astro Boy and Cowboy Bebop) depicted and generated nationally and ethnically diverse audiences. -

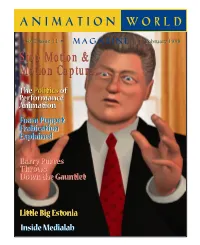

Stop Motion & Motion Capture Stop Motion

VolVol 22 IssueIssue 1111 February 1998 Stop Motion & Motion Capture The Politics of Performance Animation FoamFoam PuppetPuppet FrabicationFrabication ExplainedExplained BarryBarry Purves Purves ThrowsThrows DownDown thethe GauntletGauntlet Little Big Estonia InsideInside MedialabMedialab Table of Contents February, 1998 Vol. 2, No. 11 4 Editor’s Notebook Animation and its many changing faces... 5 Letters: [email protected] STOP-MOTION & MOTION-CAPTURE 6 Who’s Data Is That Anyway? Gregory Peter Panos, founding co-director of the Performance Animation Society, describes a new fron- tier of dilemmas, the politics of performance animation. 9 Boldly Throwing Down the Gauntlet In our premier issue, acclaimed stop-motion animator Barry J.C. Purves shared his sentiments on the coming of the computer. Now Barry’s back to share his thoughts on the last two years that have been both exhilarating and disappointing for him. 14 A Conversation With... In a small, quiet cafe, motion-capture pioneer Chris Walker and outrageous stop-motion animator Corky Quakenbush got together for lunch and discovered that even though their techniques may appear to be night and day, they actually have a lot in common. 21 At Last, Foam Puppet Fabrication Explained! How does one build an armature from scratch and end up with a professional foam puppet? Tom Brierton is here to take us through the steps and offer advice. 27 Little Big Estonia:The Nukufilm Studio On the 40th anniversary of Estonia’s Nukufilm, Heikki Jokinen went for a visit to profile the puppet ani- mation studio and their place in the post-Soviet world. 31 Wallace & Gromit Spur Worldwide Licensing Activity Karen Raugust takes a look at the marketing machine behind everyone’s favorite clay characters, Wallace & Gromit. -

The Animated Movie Guide

THE ANIMATED MOVIE GUIDE Jerry Beck Contributing Writers Martin Goodman Andrew Leal W. R. Miller Fred Patten An A Cappella Book Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Beck, Jerry. The animated movie guide / Jerry Beck.— 1st ed. p. cm. “An A Cappella book.” Includes index. ISBN 1-55652-591-5 1. Animated films—Catalogs. I. Title. NC1765.B367 2005 016.79143’75—dc22 2005008629 Front cover design: Leslie Cabarga Interior design: Rattray Design All images courtesy of Cartoon Research Inc. Front cover images (clockwise from top left): Photograph from the motion picture Shrek ™ & © 2001 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Photograph from the motion picture Ghost in the Shell 2 ™ & © 2004 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Mutant Aliens © Bill Plympton; Gulliver’s Travels. Back cover images (left to right): Johnny the Giant Killer, Gulliver’s Travels, The Snow Queen © 2005 by Jerry Beck All rights reserved First edition Published by A Cappella Books An Imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 1-55652-591-5 Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 For Marea Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction ix About the Author and Contributors’ Biographies xiii Chronological List of Animated Features xv Alphabetical Entries 1 Appendix 1: Limited Release Animated Features 325 Appendix 2: Top 60 Animated Features Never Theatrically Released in the United States 327 Appendix 3: Top 20 Live-Action Films Featuring Great Animation 333 Index 335 Acknowledgments his book would not be as complete, as accurate, or as fun without the help of my ded- icated friends and enthusiastic colleagues.