Frederick S. Litten a Mixed Picture Drawn Animation/Live Action Hybrids

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPA : Redesigning Animation

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. UPA : redesigning animation Bottini, Cinzia 2016 Bottini, C. (2016). UPA : redesigning animation. Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/69065 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/69065 Downloaded on 05 Oct 2021 20:18:45 SGT UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI SCHOOL OF ART, DESIGN AND MEDIA 2016 UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI School of Art, Design and Media A thesis submitted to the Nanyang Technological University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.” Paul Klee, “Creative Credo” Acknowledgments When I started my doctoral studies, I could never have imagined what a formative learning experience it would be, both professionally and personally. I owe many people a debt of gratitude for all their help throughout this long journey. I deeply thank my supervisor, Professor Heitor Capuzzo; my cosupervisor, Giannalberto Bendazzi; and Professor Vibeke Sorensen, chair of the School of Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore for showing sincere compassion and offering unwavering moral support during a personally difficult stage of this Ph.D. I am also grateful for all their suggestions, critiques and observations that guided me in this research project, as well as their dedication and patience. My gratitude goes to Tee Bosustow, who graciously -

John Stamos Helps Inspire Youngsters on WE

August 10 - 16, 2018 2 x 2" ad 2 x 2" ad John Stamos H K M F E D A J O M I Z A G U 2 x 3" ad W I X I D I M A G G I O I R M helps inspire A N B W S F O I L A R B X O M Y G L E H A D R A N X I L E P 2 x 3.5" ad C Z O S X S D A C D O R K N O youngsters I O C T U T B V K R M E A I V J G V Q A J A X E E Y D E N A B A L U C I L Z J N N A C G X on WE Day R L C D D B L A B A T E L F O U M S O R C S C L E B U C R K P G O Z B E J M D F A K R F A F A X O N S A G G B X N L E M L J Z U Q E O P R I N C E S S John Stamos is O M A F R A K N S D R Z N E O A N R D S O R C E R I O V A H the host of the “Disenchantment” on Netflix yearly WE Day Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Bean (Abbi) Jacobson Princess special, which Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 Luci (Eric) Andre Dreamland ABC presents Merchandise High-End 2 x 3" ad Elfo (Nat) Faxon Misadventures King Zog (John) DiMaggio Oddballs 1 x 4" ad Friday. -

Bruno Bozzetto

26/5/2015 www.unibg.it/static_content/presentazioneateneo/lhbozzetto.htm#conferimento Bruno Bozzetto laurea specialistica honoris causa in Teoria, tecniche e gestione delle arti e dello spettacolo a.a. 2006/2007 lectio magistralis conferimento elogio Bruno Bozzetto Lectio Magistralis Magnifico Rettore, Professori, Autorità, amici e studenti, non credo d'essere molto originale dicendo di sentirmi emozionato, e questo non solo per il grande onore che oggi mi viene reso, ma perché il mio mezzo di comunicazione sono sempre stati i disegni, e ora devo invece usare le parole... Un mezzo che, nel mio caso personale, non esiterei a definire decisamente "improprio". Proprio per questo, ben conoscendo i miei limiti, ho deciso di scrivere le mie parole e di farmi sostenere con la proiezione di qualche film. Prima di iniziare desidero però ringraziare sentitamente il Magnifico Rettore, professor Alberto Castoldi, e tutti coloro che mi hanno proposto per questa onorificenza, che rappresenta per me, per la mia professione e per tutti i collaboratori uno dei momenti più gratificanti. Desidero innanzitutto cogliere questa bella opportunità per ricordare pubblicamente la figura di mio padre Umberto, una persona straordinaria, senza il cui aiuto morale e finanziario non avrei mai potuto intraprendere questa attività. Nella vita la fortuna gioca sempre un ruolo fondamentale, e probabilmente tutti noi, se non ci fossimo trovati nel luogo giusto al momento giusto, avremmo scelto altre carriere ed altre direzioni. La mia grande fortuna è stata quella di nascere in una splendida famiglia com'era la mia, con un padre eccezionale, creativo, dinamico e soprattutto lungimirante, che ha sempre rappresentato per me, oggi come allora, una fonte inesauribile d'ispirazione, da cui ho attinto idee, spirito critico e soprattutto il coraggio di intraprendere una carriera così particolare ed a quei tempi così poco promettente. -

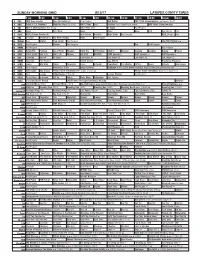

Sunday Morning Grid 8/13/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 8/13/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Bull Riding 2017 PGA Championship Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Triathlon From Kailua-Kona, Hawaii. IAAF World Championships 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Invitation to Fox News Sunday News Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program The Pink Panther ›› 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program The Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Cooking Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bali (TVG) Bali (TVG) Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ KCET Special Å KCET Special Å KCET Special Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Central Liga MX (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Recuerda y Gana Juego Estrellas Gladiator ››› (2000, Drama Histórico) Russell Crowe, Joaquin Phoenix. -

Der Prozess Der Deutschen Wiedervereinigung Aus Der Sicht Der Angelsächsischen Partner, Dem Vereinigten Königreich Und Den Vereinigten Staaten Von Amerika

1 Dissertation Der Prozess der deutschen Wiedervereinigung aus der Sicht der angelsächsischen Partner, dem Vereinigten Königreich und den Vereinigten Staaten von Amerika von Jörg Beck betreut durch Herrn Professor Dr. Hermann Hiery Lehrstuhl für Neueste Geschichte an der Universität Bayreuth Zweitkorrektor: Professor Dr. Jan-Otmar Hesse 2 Zum sehr großen Dank für die extrem starke Unterstützung an meine Mutter Frau Ilse Beck 3 Vorwort Die Dissertation „Der Prozess der Deutschen Wiedervereinigung aus der Sicht der angelsächsischen Partnerstaaten, dem Vereinigten Königreich und den Vereinigten Staaten von Amerika“ an der Kulturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Bayreuth wurde begutachtet von Herrn Professor Dr. Hermann Hiery, Inhaber des Lehrstuhls für Neueste Geschichte an der Kulturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Bayreuth und Herrn Professor Dr. Jan-Otmar Hesse, Inhaber des Lehrstuhls für Wirtschafts- und Sozialgeschichte an der Kulturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Bayreuth. Die Dissertation wurde am 15. November 2017 angenommen. Jörg Beck Bayreuth, 24. Juli 2019 4 5 Inhaltsverzeichnis Seite Einleitung 8 A Problembereich und Fragestellungen 8 B Zum Forschungsinteresse der Kapitel im Einzelnen 9 C Forschungsstand 12 C 1 Forschungsstand in der Sekundärliteratur 12 C 2 Überblick und Kritik der verwendeten Quellen 15 Methodik 25 Materialzugang 25 Der Prozess der deutschen Wiedervereinigung aus der Sicht der angelsächsischen Partner, dem Vereinigten Königreich und den Vereinigten Staaten von Amerika 29 1 Das -

'Duncanville' Is A

Visit Our Showroom To Find The Perfect Lift Bed For You! February 14 - 20, 2020 2 x 2" ad 300 N Beaton St | Corsicana | 903-874-82852 x 2" ad M-F 9am-5:30pm | Sat 9am-4pm milesfurniturecompany.com FREE DELIVERY IN LOCAL AREA WA-00114341 The animated, Amy Poehler- T M O T H U Q Z A T T A C K P Your Key produced 2 x 3" ad P U B E N C Y V E L L V R N E comedy R S Q Y H A G S X F I V W K P To Buying Z T Y M R T D U I V B E C A N and Selling! “Duncanville” C A T H U N W R T T A U N O F premieres 2 x 3.5" ad S F Y E T S E V U M J R C S N Sunday on Fox. G A C L L H K I Y C L O F K U B W K E C D R V M V K P Y M Q S A E N B K U A E U R E U C V R A E L M V C L Z B S Q R G K W B R U L I T T L E I V A O T L E J A V S O P E A G L I V D K C L I H H D X K Y K E L E H B H M C A T H E R I N E M R I V A H K J X S C F V G R E N C “War of the Worlds” on Epix Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Bill (Ward) (Gabriel) Byrne Aliens Place your classified Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 Helen (Brown) (Elizabeth) McGovern (Savage) Attack ad in the Waxahachie Daily Light, Merchandise High-End 2 x 3" ad Catherine (Durand) (Léa) Drucker Europe Midlothian Mirror and Ellis Mustafa (Mokrani) (Adel) Bencherif (Fight for) Survival County Trading1 Post! x 4" ad Deal Merchandise Word Search Sarah (Gresham) (Natasha) Little (H.G.) Wells Call (972) 937-3310 Run a single item Run a single item priced at $50-$300 priced at $301-$600 for only $7.50 per week for only $15 per week 6 lines runs in The Waxahachie Daily Light, ‘Duncanville’ is a new Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Trading2 x 3.5" Post ad and online at waxahachietx.com All specials are pre-paid. -

Animation Stagnation Or: How America Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Mouse by Billy Tooma

Animation Stagnation or: How America Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Mouse by Billy Tooma With all the animated flms that come out reason behind this is that Disney just keeps these days, it can actually be somewhat difcult putting out one hit after another and audiences to distinguish a Disney-made one from the expect perfection each time. Unfortunately, for others, seeing as how the competition tries on a the company that has made Mickey Mouse a consistent basis to copy the style that Walt Disney household name for over 90 years, that isn’t the himself unofcially trademarked as far back as case. Even though people are showing up to the the late 1920s. Te very thought that something cinemas, they aren’t doing it because they expect is being put out by Disney can lead to biased to see a screen gem. Tey’re doing it because appeal. In 1994, Warner Bros. had produced an it’s felt that they owe something, possibly their animated feature entitled Tumbelina. In one childhood, to Disney. But, does that mean of its frst test screenings, the overall audience people are being foolish for constantly shelling consensus was low, discouraging the executives out money to see a Disney animated flm every because they felt theirs was as fne a product as year or so? Te answer is ‘no,’ because Disney their competition. In an unprecedented move, was able to gain such an early monopoly on Warner Bros. stripped their logo from the flm’s the industry that it allowed them to prevent opening and replaced it with the Disney one. -

Self Advocacy Speakout January 2021

SELF ADVOCACY SPEAKOUT January 2021 Why I Love to Bake My Kent State JoUrney By Anja Calior By Olivia Parker I love to bake all things from cookies to Since COVID-19 happened, I could not cakes and everything in between. Why, attend the day program like I used to, so I you ask? It's because it smells so good started attending Kent State University in and I just get so much joy out of it! It's also Trumbull County. I do this virtually through nice to bake for others, especially when they Siffrin Academy and I love it. My teacher's aren't expecting it. name is Lauren and she is so amazing and fun. The One of my favorite desserts to bake was the black cherry tart activities that we have done so far include chair yoga, I made in my culinary class when I was in school. They were money management, attend book club, discussed self- really yummy! However, I can think of lots of desserts that I advocacy, history, grammar, science, and sign language. like to make. I also love to come up with all sorts of different We've also discussed movies and worked on math skills. I ways to decorate my desserts. I would really like to have a have a lot of friends that attend Siffrin Academy with me. I job as a baker/decorator. wouldn't want to go anywhere else to learn. I'm looking I need some adaptions to make baking safe for me such as a forward to attending classes on campus next year. -

PROGRAM NOTES Disney in Concert: Around the World Quincy Symphony Orchestra September 29, 2019 Quincy, IL Notes by Dr

PROGRAM NOTES Disney in Concert: Around the World Quincy Symphony Orchestra September 29, 2019 Quincy, IL Notes by Dr. Paul Borg We begin our season with a generous offering of music from the films of the Walt Disney Company [Walt Disney Productions until 1986]. When Walt Disney died in 1966, the corporation continued his inspired and successful animated-film output. Although not all of nearly 200 animations, live-action films, television series, documentaries, or videos are equally memorable, everyone today has heard many of the songs associated with the films, whether from viewing the films, listening to recordings, or in live concerts such as this one. In the late 1920s and 30s films had newly been furnished with recorded sound, giving motion pictures real-time spoken dialogue among the characters as well as music that could entertain with songs embedded in the storyline. Music could also be employed to enhance or evoke a particular emotion--think the spooky two-note shark approach in Jaws or the "screeching" of the knife in the shower scene of Psycho. Walt Disney and his brother Roy extended these sound element to animated cartoons, short at first (Steamboat Willie) and eventually feature length (Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs). Disney's intent to continue a series of fairy tale animations was interrupted by the Second World War, during which he and his collaborators produced a series of training and propaganda films, even using Donald Duck in some comical short sketches. After the war, Disney turned his vision to television and then his entertainment parks, starting with Disneyland in 1955. -

2019 Sarasota-Manatee Jewish Community Study V

Sponsored in part by 2019 a grant from: Cohen Center Authors: Matthew Boxer Jewish Community Study Matthew A. Brookner Eliana Chapman A socio-demographic portrait of the Jewish Janet Krasner Aronson community in Sarasota-Manatee © 2019 Brandeis University Maurice and Marilyn Cohen Center for Modern Jewish Studies www.brandeis.edu/cmjs The Jewish Federation of Sarasota-Manatee https://www.jfedsrq.org/ The Cohen Center for Modern Jewish Studies (CMJS), founded in 1980, is dedicated to providing independent, high-quality research on issues related to contemporary Jewish life. The Cohen Center is also the home of the Steinhardt Social Research Institute (SSRI). Established in 2005, SSRI uses innovative research methods to collect and analyze socio- demographic data on the Jewish community. Jewish Federation Acknowledgments It is with pride and a sense of accomplishment that we present the findings of our 2019 Jewish Community Study. The Jewish Federation of Sarasota-Manatee has a vision to build a vibrant, inclusive, engaged Jewish community. To realize this vision, our leadership felt strongly that we must better understand the demographics of our Jewish community and the attitudes and needs of its residents. To address this, our Federation invested in a comprehensive study of our local Jewish community. This study will significantly impact the strategy and work of our Federation, helping us to better understand communal needs so that we can allocate our precious resources for maximum impact. The results are especially important and timely as we embark on a project to reimagine our 32-acre Larry Greenspon Family Campus for Jewish Life on McIntosh Road. -

Reading Resources E.O.C. Reading

Reading Resources for E.O.C. Reading SOL Paired Passages New SOL Question Formats Reading and Thinking Resources Inference Comprehension Resources Literature Resources State Testing Resources Developed by High School Reading Specialists Loudoun County Public Schools March 2013 Page 1 of 245 Purpose This booklet is designed for LCPS High School English Teachers and Reading Specialists to use during classroom instruction as we prepare our 11th grade students for the upcoming spring E.O.C. Reading SOL. The Virginia Department of Education has changed the format and content of the E.O.C. Reading SOL test. The new test will contain paired passages and newly formatted questions. Students will be expected to read and to compare nonfiction, fiction, or a poem focused on the same topic. Students will answer questions about the paired passages and will be expected to answer questions comparing the content, style, theme, purpose, and intended audience for both passages. The paired passages in this booklet are literature selections from various state released E.O.C. Reading tests. The LCPS High School Reading Specialists wrote test questions for these passages using the new released VA DOE question formats. In addition, the High School Reading Specialists contributed helpful reading and literature tips that can be used during classroom instruction to prepare our students. High School Reading Specialists Loudoun County Public Schools Page 2 of 245 These Loudoun County Public High School Reading Specialists put forth time and effort to create this resource booklet for teachers and students. Dr. Dianne Kinkead, LCPS Reading Supervisor K-12 Jane Haugh, Ph.D. -

All Choked Up

All Choked Up H EAVY TR AFFIC, D IR TY AIR AN D TH E R ISK TO N EW YO R K ER S M AR C H 2007 Acknowledgments Environmental Defense would like to thank the following funders for making this work possible: Gilbert and Ildiko Butler Foundation, Surdna Foundation, The New York Community Trust, The Scherman Foundation and the High Meadows Fellows Program. The following staff contributed to this report: Dr. John Balbus MD, Mel Peffers, Michael Replogle, Peter Black, Andy Darrell, Ramon Cruz, Carol Rosenfeld, Tom Elson and Sarah Barbrow. Thanks also to Dr. Jonathan Levy, Harvard School of Public Health, for his help with the health portion of the report and his permission to discuss his research here. Thanks also to Ann Seligman, for writing and outreach, and Monica Bansal, for assistance with mapping. Cover photo: Ian Britton @ FreeFoto.com Figures 1 & 2: Lisa Paruch Our mission Environmental Defense is dedicated to protecting the environmental rights of all people, including the right to clean air, clean water, healthy food and flourishing ecosystems. Guided by science, we work to create practical solutions that win lasting political, economic and social support because they are nonpartisan, cost-effective and fair. © 2007 Environmental Defense Printed on 80% recycled paper (60% post consumer), processed chlorine free. The report is available online at www.allchokedup.org. ii Executive summary New York is a city of superlatives. It’s America’s oldest big city and a place that’s constantly reinventing itself. It’s a place where millions of people raise their families and build careers, a destination spot for tourists and immigrants from around the world, and a cultural and financial center.