A Century of Noether's Theorem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

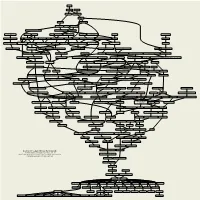

Academic Genealogy of George Em Karniadakis

Nilos Kabasilas Demetrios Kydones Elissaeus Judaeus Manuel Chrysoloras Georgios Plethon Gemistos 1380, 1393 Basilios Bessarion 1436 Mystras Guarino da Verona Johannes Argyropoulos 1408 1444 Università di Padova Vittorino da Feltre Cristoforo Landino Marsilio Ficino 1416 Università di Padova 1462 Università di Firenze Ognibene (Omnibonus Leonicenus) Bonisoli da Lonigo Theodoros Gazes Angelo Poliziano Università di Mantova 1433 Constantinople / Università di Mantova 1477 Università di Firenze Leo Outers Alessandro Sermoneta Gaetano da Thiene Moses Perez Scipione Fortiguerra Demetrios Chalcocondyles Jacob ben Jehiel Loans Rudolf Agricola Thomas à Kempis Heinrich von Langenstein 1485 Université Catholique de Louvain 1493 Università di Firenze 1452 Mystras / Accademia Romana 1478 Università degli Studi di Ferrara 1363, 1375 Université de Paris Maarten (Martinus Dorpius) van Dorp Pelope Pietro Roccabonella Nicoletto Vernia François Dubois Jean Tagault Girolamo (Hieronymus Aleander) Aleandro Janus Lascaris Matthaeus Adrianus Johann (Johannes Kapnion) Reuchlin Jan Standonck Alexander Hegius Johannes von Gmunden 1504, 1515 Université Catholique de Louvain Università di Padova Università di Padova 1516 Université de Paris 1499, 1508 Università di Padova 1472 Università di Padova 1477, 1481 Universität Basel / Université de Poitiers 1474, 1490 Collège Sainte-Barbe / Collège de Montaigu 1474 1406 Universität Wien Niccolò Leoniceno Jacobus (Jacques Masson) Latomus Desiderius Erasmus Petrus (Pieter de Corte) Curtius Pietro Pomponazzi Jacobus (Jacques -

Karl Weierstraß – Zum 200. Geburtstag „Alles Im Leben Kommt Doch Leider Zu Spät“ Reinhard Bölling Universität Potsdam, Institut Für Mathematik Prolog Nunmehr Im 74

1 Karl Weierstraß – zum 200. Geburtstag „Alles im Leben kommt doch leider zu spät“ Reinhard Bölling Universität Potsdam, Institut für Mathematik Prolog Nunmehr im 74. Lebensjahr stehend, scheint es sehr wahrscheinlich, dass dies mein einziger und letzter Beitrag über Karl Weierstraß für die Mediathek meiner ehemaligen Potsdamer Arbeitsstätte sein dürfte. Deshalb erlaube ich mir, einige persönliche Bemerkungen voranzustellen. Am 9. November 1989 ging die Nachricht von der Öffnung der Berliner Mauer um die Welt. Am Tag darauf schrieb mir mein Freund in Stockholm: „Herzlich willkommen!“ Ich besorgte das damals noch erforderliche Visum in der Botschaft Schwedens und fuhr im Januar 1990 nach Stockholm. Endlich konnte ich das Mittag- Leffler-Institut in Djursholm, im nördlichen Randgebiet Stockholms gelegen, besuchen. Dort befinden sich umfangreiche Teile des Nachlasses von Weierstraß und Kowalewskaja, die von Mittag-Leffler zusammengetragen worden waren. Ich hatte meine Arbeit am Briefwechsel zwischen Weierstraß und Kowalewskaja, die meine erste mathematikhistorische Publikation werden sollte, vom Inhalt her abgeschlossen. Das Manuskript lag in nahezu satzfertiger Form vor und sollte dem Verlag übergeben werden. Geradezu selbstverständlich wäre es für diese Arbeit gewesen, die Archivalien im Mittag-Leffler-Institut zu studieren. Aber auch als Mitarbeiter des Karl-Weierstraß- Institutes für Mathematik in Ostberlin gehörte ich nicht zu denen, die man ins westliche Ausland reisen ließ. – Nun konnte ich mir also endlich einen ersten Überblick über die Archivalien im Mittag-Leffler-Institut verschaffen. Ich studierte in jenen Tagen ohne Unterbrechung von morgens bis abends Schriftstücke, Dokumente usw. aus dem dortigen Archiv, denn mir stand nur eine Woche zur Verfügung. Am zweiten Tag in Djursholm entdeckte ich unter Papieren ganz anderen Inhalts einige lose Blätter, die Kowalewskaja beschrieben hatte. -

Halloweierstrass

Happy Hallo WEIERSTRASS Did you know that Weierestrass was born on Halloween? Neither did we… Dmitriy Bilyk will be speaking on Lacunary Fourier series: from Weierstrass to our days Monday, Oct 31 at 12:15pm in Vin 313 followed by Mesa Pizza in the first floor lounge Brought to you by the UMN AMS Student Chapter and born in Ostenfelde, Westphalia, Prussia. sent to University of Bonn to prepare for a government position { dropped out. studied mathematics at the M¨unsterAcademy. University of K¨onigsberg gave him an honorary doctor's degree March 31, 1854. 1856 a chair at Gewerbeinstitut (now TU Berlin) professor at Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universit¨atBerlin (now Humboldt Universit¨at) died in Berlin of pneumonia often cited as the father of modern analysis Karl Theodor Wilhelm Weierstrass 31 October 1815 { 19 February 1897 born in Ostenfelde, Westphalia, Prussia. sent to University of Bonn to prepare for a government position { dropped out. studied mathematics at the M¨unsterAcademy. University of K¨onigsberg gave him an honorary doctor's degree March 31, 1854. 1856 a chair at Gewerbeinstitut (now TU Berlin) professor at Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universit¨atBerlin (now Humboldt Universit¨at) died in Berlin of pneumonia often cited as the father of modern analysis Karl Theodor Wilhelm Weierstraß 31 October 1815 { 19 February 1897 born in Ostenfelde, Westphalia, Prussia. sent to University of Bonn to prepare for a government position { dropped out. studied mathematics at the M¨unsterAcademy. University of K¨onigsberg gave him an honorary doctor's degree March 31, 1854. 1856 a chair at Gewerbeinstitut (now TU Berlin) professor at Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universit¨atBerlin (now Humboldt Universit¨at) died in Berlin of pneumonia often cited as the father of modern analysis Karl Theodor Wilhelm Weierstraß 31 October 1815 { 19 February 1897 sent to University of Bonn to prepare for a government position { dropped out. -

Classics in Mathematics Richard Courant· Fritz John Introduction To

Classics in Mathematics Richard Courant· Fritz John Introduction to Calculus and Analysis Volume I Springer-V erlag Berlin Heidelberg GmbH Richard Courant • Fritz John Introd uction to Calculus and Analysis Volume I Reprint of the 1989 Edition Springer Originally published in 1965 by Interscience Publishers, a division of John Wiley and Sons, Inc. Reprinted in 1989 by Springer-Verlag New York, Inc. Mathematics Subject Classification (1991): 26-XX, 26-01 Cataloging in Publication Data applied for Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Courant, Richard: Introduction to calcu1us and analysis / Richard Courant; Fritz John.- Reprint of the 1989 ed.- Berlin; Heidelberg; New York; Barcelona; Hong Kong; London; Milan; Paris; Singapore; Tokyo: Springer (Classics in mathematics) VoL 1 (1999) ISBN 978-3-540-65058-4 ISBN 978-3-642-58604-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-58604-0 Photograph of Richard Courant from: C. Reid, Courant in Gottingen and New York. The Story of an Improbable Mathematician, Springer New York, 1976 Photograph of Fritz John by kind permission of The Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences, New York ISSN 1431-0821 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved. whether the whole or part of the material is concemed. specifically the rights of trans1ation. reprinting. reuse of illustrations. recitation. broadcasting. reproduction on microfilm or in any other way. and storage in data banks. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted onlyunder the provisions of the German Copyright Law of September 9.1965. in its current version. and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer-Verlag. Violations are Iiable for prosecution under the German Copyright Law. -

A Century of Mathematics in America, Peter Duren Et Ai., (Eds.), Vol

Garrett Birkhoff has had a lifelong connection with Harvard mathematics. He was an infant when his father, the famous mathematician G. D. Birkhoff, joined the Harvard faculty. He has had a long academic career at Harvard: A.B. in 1932, Society of Fellows in 1933-1936, and a faculty appointmentfrom 1936 until his retirement in 1981. His research has ranged widely through alge bra, lattice theory, hydrodynamics, differential equations, scientific computing, and history of mathematics. Among his many publications are books on lattice theory and hydrodynamics, and the pioneering textbook A Survey of Modern Algebra, written jointly with S. Mac Lane. He has served as president ofSIAM and is a member of the National Academy of Sciences. Mathematics at Harvard, 1836-1944 GARRETT BIRKHOFF O. OUTLINE As my contribution to the history of mathematics in America, I decided to write a connected account of mathematical activity at Harvard from 1836 (Harvard's bicentennial) to the present day. During that time, many mathe maticians at Harvard have tried to respond constructively to the challenges and opportunities confronting them in a rapidly changing world. This essay reviews what might be called the indigenous period, lasting through World War II, during which most members of the Harvard mathe matical faculty had also studied there. Indeed, as will be explained in §§ 1-3 below, mathematical activity at Harvard was dominated by Benjamin Peirce and his students in the first half of this period. Then, from 1890 until around 1920, while our country was becoming a great power economically, basic mathematical research of high quality, mostly in traditional areas of analysis and theoretical celestial mechanics, was carried on by several faculty members. -

Foundations of Geometry

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2008 Foundations of geometry Lawrence Michael Clarke Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Geometry and Topology Commons Recommended Citation Clarke, Lawrence Michael, "Foundations of geometry" (2008). Theses Digitization Project. 3419. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/3419 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Foundations of Geometry A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Mathematics by Lawrence Michael Clarke March 2008 Foundations of Geometry A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Lawrence Michael Clarke March 2008 Approved by: 3)?/08 Murran, Committee Chair Date _ ommi^yee Member Susan Addington, Committee Member 1 Peter Williams, Chair, Department of Mathematics Department of Mathematics iii Abstract In this paper, a brief introduction to the history, and development, of Euclidean Geometry will be followed by a biographical background of David Hilbert, highlighting significant events in his educational and professional life. In an attempt to add rigor to the presentation of Geometry, Hilbert defined concepts and presented five groups of axioms that were mutually independent yet compatible, including introducing axioms of congruence in order to present displacement. -

Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach Emigration Of

Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach Report No. 51/2011 DOI: 10.4171/OWR/2011/51 Emigration of Mathematicians and Transmission of Mathematics: Historical Lessons and Consequences of the Third Reich Organised by June Barrow-Green, Milton-Keynes Della Fenster, Richmond Joachim Schwermer, Wien Reinhard Siegmund-Schultze, Kristiansand October 30th – November 5th, 2011 Abstract. This conference provided a focused venue to explore the intellec- tual migration of mathematicians and mathematics spurred by the Nazis and still influential today. The week of talks and discussions (both formal and informal) created a rich opportunity for the cross-fertilization of ideas among almost 50 mathematicians, historians of mathematics, general historians, and curators. Mathematics Subject Classification (2000): 01A60. Introduction by the Organisers The talks at this conference tended to fall into the two categories of lists of sources and historical arguments built from collections of sources. This combi- nation yielded an unexpected richness as new archival materials and new angles of investigation of those archival materials came together to forge a deeper un- derstanding of the migration of mathematicians and mathematics during the Nazi era. The idea of measurement, for example, emerged as a critical idea of the confer- ence. The conference called attention to and, in fact, relied on, the seemingly stan- dard approach to measuring emigration and immigration by counting emigrants and/or immigrants and their host or departing countries. Looking further than this numerical approach, however, the conference participants learned the value of measuring emigration/immigration via other less obvious forms of measurement. 2892 Oberwolfach Report 51/2011 Forms completed by individuals on religious beliefs and other personal attributes provided an interesting cartography of Italian society in the 1930s and early 1940s. -

Implications for Understanding the Role of Affect in Mathematical Thinking

Mathematicians and music: Implications for understanding the role of affect in mathematical thinking Rena E. Gelb Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2021 © 2021 Rena E. Gelb All Rights Reserved Abstract Mathematicians and music: Implications for understanding the role of affect in mathematical thinking Rena E. Gelb The study examines the role of music in the lives and work of 20th century mathematicians within the framework of understanding the contribution of affect to mathematical thinking. The current study focuses on understanding affect and mathematical identity in the contexts of the personal, familial, communal and artistic domains, with a particular focus on musical communities. The study draws on published and archival documents and uses a multiple case study approach in analyzing six mathematicians. The study applies the constant comparative method to identify common themes across cases. The study finds that the ways the subjects are involved in music is personal, familial, communal and social, connecting them to communities of other mathematicians. The results further show that the subjects connect their involvement in music with their mathematical practices through 1) characterizing the mathematician as an artist and mathematics as an art, in particular the art of music; 2) prioritizing aesthetic criteria in their practices of mathematics; and 3) comparing themselves and other mathematicians to musicians. The results show that there is a close connection between subjects’ mathematical and musical identities. I identify eight affective elements that mathematicians display in their work in mathematics, and propose an organization of these affective elements around a view of mathematics as an art, with a particular focus on the art of music. -

Professor Richard Courant (1888 – 1972)

Professor Richard Courant (1888 – 1972) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Courant Field: Mathematics Institutions: University of Göttingen University of Münster University of Cambridge New York University Alma mater: University of Göttingen Doctoral advisor: David Hilbert Doctoral students: William Feller Martin Kruskal Joseph Keller Kurt Friedrichs Hans Lewy Franz Rellich Known for: Courant number Courant minimax principle Courant–Friedrichs–Lewy condition Biography: Courant was born in Lublinitz in the German Empire's Prussian Province of Silesia. During his youth, his parents had to move quite often, to Glatz, Breslau, and in 1905 to Berlin. He stayed in Breslau and entered the university there. As he found the courses not demanding enough, he continued his studies in Zürich and Göttingen. Courant eventually became David Hilbert's assistant in Göttingen and obtained his doctorate there in 1910. He had to fight in World War I, but he was wounded and dismissed from the military service shortly after enlisting. After the war, in 1919, he married Nerina (Nina) Runge, a daughter of the Göttingen professor for Applied Mathematics, Carl Runge. Richard continued his research in Göttingen, with a two-year period as professor in Münster. There he founded the Mathematical Institute, which he headed as director from 1928 until 1933. Courant left Germany in 1933, earlier than many of his colleagues. While he was classified as a Jew by the Nazis, his having served as a front-line soldier exempted him from losing his position for this particular reason at the time; however, his public membership in the social-democratic left was a reason for dismissal to which no such exemption applied.[1] After one year in Cambridge, Courant went to New York City where he became a professor at New York University in 1936. -

1 INTRO Welcome to Biographies in Mathematics Brought to You From

INTRO Welcome to Biographies in Mathematics brought to you from the campus of the University of Texas El Paso by students in my history of math class. My name is Tuesday Johnson and I'll be your host on this tour of time and place to meet the people behind the math. EPISODE 1: EMMY NOETHER There were two women I first learned of when I started college in the fall of 1990: Hypatia of Alexandria and Emmy Noether. While Hypatia will be the topic of another episode, it was never a question that I would have Amalie Emmy Noether as my first topic of this podcast. Emmy was born in Erlangen, Germany, on March 23, 1882 to Max and Ida Noether. Her father Max came from a family of wholesale hardware dealers, a business his grandfather started in Bruchsal (brushal) in the early 1800s, and became known as a great mathematician studying algebraic geometry. Max was a professor of mathematics at the University of Erlangen as well as the Mathematics Institute in Erlangen (MIE). Her mother, Ida, was from the wealthy Kaufmann family of Cologne. Both of Emmy’s parents were Jewish, therefore, she too was Jewish. (Judiasm being passed down a matrilineal line.) Though Noether is not a traditional Jewish name, as I am told, it was taken by Elias Samuel, Max’s paternal grandfather when in 1809 the State of Baden made the Tolerance Edict, which required Jews to adopt Germanic names. Emmy was the oldest of four children and one of only two who survived childhood. -

Emmy Noether, Greatest Woman Mathematician Clark Kimberling

Emmy Noether, Greatest Woman Mathematician Clark Kimberling Mathematics Teacher, March 1982, Volume 84, Number 3, pp. 246–249. Mathematics Teacher is a publication of the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM). With more than 100,000 members, NCTM is the largest organization dedicated to the improvement of mathematics education and to the needs of teachers of mathematics. Founded in 1920 as a not-for-profit professional and educational association, NCTM has opened doors to vast sources of publications, products, and services to help teachers do a better job in the classroom. For more information on membership in the NCTM, call or write: NCTM Headquarters Office 1906 Association Drive Reston, Virginia 20191-9988 Phone: (703) 620-9840 Fax: (703) 476-2970 Internet: http://www.nctm.org E-mail: [email protected] Article reprinted with permission from Mathematics Teacher, copyright March 1982 by the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. All rights reserved. mmy Noether was born over one hundred years ago in the German university town of Erlangen, where her father, Max Noether, was a professor of Emathematics. At that time it was very unusual for a woman to seek a university education. In fact, a leading historian of the day wrote that talk of “surrendering our universities to the invasion of women . is a shameful display of moral weakness.”1 At the University of Erlangen, the Academic Senate in 1898 declared that the admission of women students would “overthrow all academic order.”2 In spite of all this, Emmy Noether was able to attend lectures at Erlangen in 1900 and to matriculate there officially in 1904. -

Fundamental Theorems in Mathematics

SOME FUNDAMENTAL THEOREMS IN MATHEMATICS OLIVER KNILL Abstract. An expository hitchhikers guide to some theorems in mathematics. Criteria for the current list of 243 theorems are whether the result can be formulated elegantly, whether it is beautiful or useful and whether it could serve as a guide [6] without leading to panic. The order is not a ranking but ordered along a time-line when things were writ- ten down. Since [556] stated “a mathematical theorem only becomes beautiful if presented as a crown jewel within a context" we try sometimes to give some context. Of course, any such list of theorems is a matter of personal preferences, taste and limitations. The num- ber of theorems is arbitrary, the initial obvious goal was 42 but that number got eventually surpassed as it is hard to stop, once started. As a compensation, there are 42 “tweetable" theorems with included proofs. More comments on the choice of the theorems is included in an epilogue. For literature on general mathematics, see [193, 189, 29, 235, 254, 619, 412, 138], for history [217, 625, 376, 73, 46, 208, 379, 365, 690, 113, 618, 79, 259, 341], for popular, beautiful or elegant things [12, 529, 201, 182, 17, 672, 673, 44, 204, 190, 245, 446, 616, 303, 201, 2, 127, 146, 128, 502, 261, 172]. For comprehensive overviews in large parts of math- ematics, [74, 165, 166, 51, 593] or predictions on developments [47]. For reflections about mathematics in general [145, 455, 45, 306, 439, 99, 561]. Encyclopedic source examples are [188, 705, 670, 102, 192, 152, 221, 191, 111, 635].