Council Part B Submission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VFL Record 2014 Rnd 1B.Indd

VFL ROUND 1 SPLIT ROUND APRIL 4-6, 2014 SSolidolid sstarttart fforor HHawksawks $3.00 Photos: Shane Goss CCollingwoodollingwood 111.19-851.19-85 d NNorthorth BBallaratallarat 111.7-731.7-73 BBoxox HHillill HHawksawks 113.17-953.17-95 d WWilliamstownilliamstown 111.16-821.16-82 AFL VICTORIA CORPORATE PARTNERS NAMING RIGHTS PREMIER PARTNERS OFFICIAL PARTNERS APPROVED LICENSEES EDITORIAL Welcome to season 2014 WELCOME to what shapes as the most fascinating, exciting and anticipated Peter Jackson VFL season we’ve witnessed in many years. Last weekend the season kicked off with three games, and Peter Jackson VFL Clubs. Nearly Round 1 is completed this weekend with another six matches 50% of the new players drafted or to start the year. rookie listed by AFL Clubs last year In many ways it is a back to the future journey with traditional originated from Victoria. In the early clubs Coburg, Footscray, Richmond and Williamstown all rounds we have already seen Luke McDonald (Werribee) and entering the 2014 season as stand-alone entities. Patrick Ambrose (Essendon VFL) debut for their respective AFL clubs North Melbourne and Essendon. And, it paves the way for some games to once again be played at spiritual grounds like the Whitten Oval and Punt Road. Certainly, AFL Victoria is delighted that Peter Jackson Further facility development work that the respective clubs are Melbourne is once again the naming rights partner of the VFL committed to will result in more games being played at these and the Toyota Victorian Dealers return as a premier partner, venues in future years. -

AFL D Contents

Powering a sporting nation: Rooftop solar potential for AFL d Contents INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................................1 AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE ...................................................................................... 3 AUSTRALIAN RULES FOOTBALL TEAMS SUMMARY RESULTS ........................4 Adelaide Football Club .............................................................................................................7 Brisbane Lions Football Club ................................................................................................ 8 Carlton Football Club ................................................................................................................ 9 Collingwood Football Club .................................................................................................. 10 Essendon Football Club ...........................................................................................................11 Fremantle Football Club .........................................................................................................12 Geelong Football Club .............................................................................................................13 Gold Coast Suns ..........................................................................................................................14 Greater Western Sydney Giants .........................................................................................16 -

AFL Vic Record Week 23.Indd

VFL Round 19 TAC Cup Round 17 21 - 23 August 2015 $3.00 Tips to avoid BetRegret Gamble less than once a week Leave your debit and credit cards at home Take breaks when gambling Don’t let it lead to something bigger. Get all the tips at betregret.com.au Authorised by the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation, Melbourne. Photo: Dave Savell Features 4 5 Nick Carnell 7 Alan Hales / Peter Henderson 9 Gary Ayres Every week Editorial 3 VFL Highlights 10 VFL News 11 TAC Cup Highlights 14 TAC Cup News 15 AFL Vic News 16 Club Whiteboard 18 21 Events 23 Get Social 24 25 Draft Watch 64 Who’s playing who 34 35 Essendon vs Footscray 52 53 North Ballarat vs Calder 36 37 Collingwood vs Richmond 54 55 Oakleigh vs Geelong 38 39 Coburg vs Casey Scorpions 56 57 Bendigo vs Northern 40 41 Northern Blues vs Box Hill Hawks 58 59 Gippsland vs Sandringham 42 43 Port Melbourne vs Frankston 60 61 Western vs Dandenong 44 45 Williamstown vs Werribee 62 63 Murray vs Eastern 46 47 Sandringham vs Geelong Editor: Ben Pollard ben.pollard@afl vic.com.au Contributors: Anthony Stanguts Design & Print: Cyan Press Photos: AFL Photos (unless otherwise credited) Ikon Park, Gate 3, Royal Parade, Carlton Nth, VIC 3054 Advertising: Ryan Webb (03) 8341 6062 GPO Box 4337, Melbourne, VIC 3001 Phone: (03) 8341 6000 | Fax: (03) 9380 1076 AFL Victoria CEO: Steven Reaper www.afl vic.com.au State League & Talent Manager: John Hook High Performance Managers: Anton Grbac, Leon Harris Cover: Dion Hill in action for Coburg during the Lions’ Talent Operations Coordinator: Rhy Gieschen Round -

Scoresheet NEWSLETTER of the AUSTRALIAN CRICKET SOCIETY INC

scoresheet NEWSLETTER OF THE AUSTRALIAN CRICKET SOCIETY INC. www.australiancricketsociety.com Volume 36 / Number 1 / SUMMER 2015 Patron: Ricky Ponting AO OUR ANNUAL FOOTY LAUNCH LUNCHEON FEATURING FRANCIS BOURKE DETAILS OF THIS FANTASTIC EVENT DATE: Friday, 10 April, 2015. TIME: 12 noon for a 12.30pm start. VENUE: The Kooyong Lawn Tennis Club 489 Glenferrie Road, Kooyong. COST: $75 for members; $85 for non-members. BOOKINGS: Bookings are essential. Bookings and monies need to be in the hands of the ACS Secretary Wayne Ross at P.O. Box 4528, Langwarrin, Vic, 3910 by no later than Tuesday, 7 April 2015. Cheques should be made payable to The ACS. Wayne’s phone number is 0416 983 888. His email address is [email protected] OUR GUEST OF HONOUR e continue the array of big names as our special guests at our dynamic Kooyong Lawn Tennis Club Luncheons Wwhich launch The AFL football season. This year’s guest is a man whose name and reputation are legendary in the football world and beyond. We are thrilled to welcome this year none other than Francis Bourke, the famous Richmond premiership player and coach. Courageous, skilled, determined, Francis Bourke began his auspicious career at Tigerland weeding the outer terraces at the Punt Road Oval with a hoe. It took him all winter to complete the job. The following season he played in his first premiership team under the much-loved Tommy Hafey. Thus began the star- studded career of Francis Bourke who played in five Richmond premiership teams – 1967, 1969, 1973, 1974, and 1980. -

Sports Funding: Federal Balancing Act

Parliament of Australia Department of Parliamentary Services BACKGROUND NOTE 27 June 2013 Sports funding: federal balancing act Dr Rhonda Jolly Social Policy Section Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Part 1: Federal Government involvement in sport .................................................................................. 3 From Federation to the Howard Government.................................................................................... 3 Federation to Whitlam .................................................................................................................. 3 Whitlam: laying the foundations of a new sports system ............................................................. 4 Fraser: dealing with the Montreal ‘crisis’ ...................................................................................... 5 Figure 1: comment on Australia’s sports system in light of its unspectacular performance in Montreal ............................................................................................................ 6 Table 1: summary of sports funding: Whitlam and Fraser Governments ..................................... 8 Hawke and Keating: a sports commission, the America’s Cup and beginning a balancing act ................................................................................................................................................ 8 Basis of policy .......................................................................................................................... -

Sports Surfaces and Facilities Advisory Services and Solutions

Sports Surfaces and Facilities Advisory Services and Solutions smartconnection.net.au A Connected Team of Smart Collaborators with One Vision To provide quality outcomes, facilities and solutions which assist our clients to grow participation in sport and active recreation Innovation Through Collaboration Innovation [in¦nov|ation] Noun transformation · metamorphosis · breakthrough · new measures · new methods · modernization · novelty · newness · creativity · originality · ingenuity · inspiration · inventiveness · a shake up Collaboration [col|lab¦or|ation ] Noun the action of working with someone to produce or create something Vision [vi·sion ] Noun foresight - the capacity to envisage future market trends and plan accordingly; Goal, a desired result Our Goal Share innovation through collaboration to support our clients’ vision by creating, transforming and enhancing perceptions from products, processes and outputs to outcomes that inspire future generations Who We Are Smart Connection Consultancy and our Collaborators offer an innovative and cohesive approach that deliver outcomes to enhance the experience of participation in physical activity, recreation and sport in local communities. The Smart Team supports our clients on all aspects of planning, procuring, installing, managing and maintaining sports surfaces and associated facilities. Sports surfaces include natural, hybrid and synthetic, as well as rubber and hard surfaces. Smart Connection Consultancy are the Technical Consultants for the Australian Rugby Union, the National Rugby League, AFL (NSW/ ACT) and Football NSW for Synthetic Surfaces. Since 2010 Smart Connection Consultancy has been at the forefront of $50m of synthetic sports turf being produced in Australia for local government, including 28 football pitches, including 5 with cricket wickets, 2 AFL ovals, 2 Rugby Union Fields and markings for 1 Rugby League field. -

VFL Record Rnd 8.Indd

VFL ROUND 8 JUNE 1-2, 2013 $3.00 CCaseyasey bbackack oonn ttrackrack Casey back on track WWilliamstownilliamstown 330.27.2070.27.207 d BBendigoendigo 55.2.32.2.32 Photos: Damian Visentini BBoxox HHillill HHawksawks 117.12.1147.12.114 d NNorthorth BBallaratallarat 114.7.914.7.91 Photos: Jenny Owens Give exit fees the boot. And lock-in contracts the hip and shoulder. AlintaAlinta EnerEnergy’sgy’s Fair GGoo 1155 • NoNo lock-inlock-in contractscontracts • No exitexit fees • 15%15% off your electricity usageusage* forfor as lonlongg as you continue to be on this planplan 18001800 46 2525 4646 alintaenergy.com.aualintaenergy.com.au *15% off your electricity usage based on Alinta Energy’s published Standing Tariffs for Victoria. Terms and conditionsconditions apply.apply. NNotot avaavailableilable wwithith sosolar.lar. EDITORIAL Positive start to Championships IT was a most encouraging start by the two Victorian teams in the opening round of the NAB AFL U18 Championships last weekend. Vic Country trekked to the Top End and returned with a into football annually in both the 100-point plus win against Northern Territory while Vic development and maintenance of Metro posted a 40-point win against Queensland from its facilities. match in the Brisbane suburb of Yeronga at AFL Qld The Forum will enhance our collective understanding of headquarters. Both sides are proudly ‘Powered by Milk’. each other’s needs and plans in the areas of participation Whilst there are many games to go, early indications are and the development of facilities for the 240,000 that this year’s Victorian teams will once again demonstrate participants in Victorian football. -

Annual Report 2011-12 Partners Contents

, Annual Report 2011-12 Partners Contents About Reclink Australia 3 Why We Exist 4 What We Do 5 Growth and Challenge 6 Corporate Governance 7 Research and Evaluation 8 Transformational Links 9 Community Partners 10 State Reports 11 Our Networks 18 Events 20 Our Activities 22 Our Members 24 Donated by Gratitude 30 Participant Stories 32 Design and production by Print donated by Midway Colour Reclink Australia Staff/Contact Us 34 Digital proofs and plates donated by Paper stock donated by The Type Factory BJ Ball Papers Photos by Glenn Hester Photography and Peter Monagle Our Mission Respond. Rebuild. Reconnect. We seek to give all participants the power of purpose. About Reclink Australia Reclink Australia is a charitable organisation whose mission is to provide sport and arts activities to enhance the lives of people experiencing disadvantage. Targeting some of the community’s most vulnerable and isolated people – those who are experiencing mental illness, disability, homelessness, substance abuse issues, addictions and social and economic hardship – Reclink Australia has facilitated cooperative partnerships with a network of over 490 member agencies committed to encouraging participation in physical and artistic activity in a population group very under-represented in mainstream sport and recreational programs and associations. We believe that sport and the arts will become accepted as a primary approach to improving the lives of those experiencing homelessness, drug and alcohol addiction and socio-economic disadvantage. Those tackling social isolation and disadvantage will seek out Reclink Australia knowing that participating in our activities will change their lives for the better. More than 9500 activities were conducted this year across Reclink Australia’s 21 networks. -

THE AMATEUR FOOTBALLER the JOURNAL of the VICTORIAN AMATEUR FOOTBALL ASSOCIATION May 28Th, 2005 Price: $2.00 Vol

VAFA RNd 7 05.qxd 30/5/05 8:02 AM Page 1 Inside the VAFA The Big V Cometh! At this time of year, chances are the mystery gentleman sitting in the grandstand furiously scribbling notes is not an opposition spy or media scribe. At VAFA grounds from A Section to D4, selectors have been doing the rounds trying to formulate teams for one of four representative matches that will take place in the upcoming weeks. In two Saturday’s time (Queen’s Birthday), the VAFA takes on the Southern Football League for the Cystic Fibrosis Community Cup. Formerly known as the St Kilda Community Cup, it features players predominantly from C Section downwards with a sprinkling from A & B Section. Traditionally, the Amateurs have held the wood on their bayside counterparts, though they have always been tight games. George Voyage is looking for his fourth straight win over the SFL and says “there is a real winning feel among the group”. “We have a group of spotters and selectors who ensure that everyone is seen in action before selection”, Voyage said. “It really is a wonderful opportunity for the boys”. Although the side has been hit hard by injuries (particularly Al Parton, who has broken his arm), it will be strengthened by several A & B Section players, several of which (Mark Liddell, Pete Harrison and Andy Cultrera) have wreaked havoc on the SFL in years past. As a curtain raiser to the game, the VAFA has implemented a new initiative, a North v South Under 19 game, which will hopefully see each Under 19 team represented. -

APPENDIX C VHR Recommendations

APPENDIX C VHR recommendations LOVELL CHEN C 1 C 2 LOVELL CHEN ASSESSMENT OF CULTURAL HERITAGE SIGNIFICANCE AND EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR RECOMMENDATION TO THE HERITAGE COUNCIL NAME ST KILDA ROAD LOCATION MELBOURNE and SOUTHBANK and ST KILDA, MELBOURNE CITY, PORT PHILLIP CITY VHR NUMBER: PROV H2359 CATEGORY: HERITAGE PLACE HERITAGE OVERLAY PARTLY IN CITY OF MELBOURNE, SOUTH MELBOURNE PRECINCT (HO5) FILE NUMBER: FOL/16/513 HERMES NUMBER: 198047 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR RECOMMENDATION TO THE HERITAGE COUNCIL: That St Kilda Road be included as a Heritage Place in the Victorian Heritage Register under the Heritage Act 1995 [Section 32 (1)(a)]. TIM SMITH Executive Director Recommendation Date: 13 May 2016 Name: St Kilda Road Hermes Number: 198047 Page | 1 EXTENT OF NOMINATION The whole of the road known as St Kilda Road, being the road reserve extending from Princes Bridge, Melbourne in the north, to the intersection with Henry Street, Melbourne in the south. It includes the roadway, medians, garden beds, kerbing, plane trees (Platanus ×acerifolia) and elm trees (Ulmus procera), and footpaths. The Edmund Fitzgibbon Memorial, located in the south-eastern median at the intersection of St Kilda Road and Linlithgow Avenue is nominated as a feature. The nominated area abuts the Princes Bridge VHR extent (H1447), but does not include it. The nomination does not include properties abutting the road reserve. Existing registrations within the nominated area It is noted that three existing registrations are included within the nominated area (Tram Shelter H1867, Tram Shelter H1868 and Tram Shelter H1869). Name: St Kilda Road Hermes Number: 198047 Page | 2 RECOMMENDED REGISTRATION DRAFT ONLY: NOT ENDORSED BY THE HERITAGE COUNCIL All of the place shown hatched on Diagram 2359 encompassing all of the road reserve for St Kilda Road beginning from the northern boundary of Alexandra Avenue to a line drawn from the south western corner of Lot 5 on Lodged Plan 33497 (649 St Kilda Road) perpendicular to the alignment of St Kilda Road. -

TAC Record Rnd 16.Indd

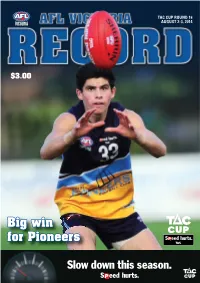

TAC CUP ROUND 16 AUGUST 2-3, 2014 $3.00 BBigig wwinin fforor PPioneersioneers CCalderalder CCannonsannons 112.13.852.13.85 d OOakleighakleigh CChargershargers 66.11.47.11.47 Photos: Dave Savell Calder Cannons 12.13.85 d Oakleigh Chargers 6.11.47 DDandenongandenong SStingraystingrays 99.10.64.10.64 d SSandringhamandringham DDragonsragons 22.10.22.10.22 AFL VICTORIA CORPORATE PARTNERS NAMING RIGHTS PREMIER PARTNERS OFFICIAL PARTNERS APPROVED LICENSEES EDITORIAL Big few weeks ahead in the race for a finals spot Eleven doesn’t fi t into eight nor does twelve or for that matter, thirteen, but these are the current scenarios as the Peter Jackson VFL season enters the business end of the home and away season. With four home and away rounds remaining in the 2014 The fi ght for a fi nals berth will provide an additional season, no fewer than 13 clubs still have a mathematical incentive of the next few weeks for not only the players chance of fi nishing in the eight and participating in the and their clubs, but also for members and supporters to VFL Legendairy fi nals series. attend games to lend their vocal support. It is not only a battle for clubs making the eight, but also The race for the TAC Cup fi nals is also intense with all those clubs within it that are jostling for a top four fi nish. clubs mathematically still in the race to play fi nals. A top four fi nish can bring the coveted double chance and What provides added interest to the fi nal few rounds of the possibility of a home fi nal in the opening week. -

Melbourne Cricket Ground's Smart Stadium Strategy

Melbourne Cricket Ground’s Smart Stadium Strategy Kyoto, Japan to Melbourne Cricket GOOGLE MAP Ground, Melbourne, GOES HERE Australia MCG Overview • The Melbourne Cricket Club (MCC) was established in 1838 and has 126,000 members and over 230,000 on the waiting list making it one of the largest sporting Clubs in the world. • The MCC is responsible for managing one of the world’s largest sporting stadiums, the Melbourne Cricket Ground (MCG). • The MCG was established in 1853 and attracts over 3.5 million patrons per year and has a capacity in excess of 100,000 patrons. • The MCG is one of the busiest stadiums in the world with over 90 event days and 1,500 non-event day functions annually. • The MCG is surrounded by Yarra Park, 32 hectares of park land which the MCC also manages. Smart Stadium Strategy – why • Theming and branding for home teams • Fan engagement • Operational efficiencies • Commercial opportunities Smart Stadium: Stage 1 v Smart Stadium Stage 2 Queue Management / Artificial Intelligence (AI) • Turns crowds into queue science • Fan visibility of wait times • Empower fans to make decisions at a glance • New directional information • Even out the crowd, new operational data • Even out the crowd, new operational data New MCG App • Research backed • Do 5 things really well • Remove pain / friction in the stadium • Make the experience more seamless • Focus on customer service • Even out the crowd new operational data Data/IT Security • ISO27001 certified, framework to protect our information assets • Protect fans information when