An Antarctic Adventure: Exploration of the Ross Ice Shelf 1957-1958

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol 39 No 48 November 26

Notice of Forfeiture - Domestic Kansas Register 1 State of Kansas 2AMD, LLC, Leawood, KS 2H Properties, LLC, Winfield, KS Secretary of State 2jake’s Jaylin & Jojo, L.L.C., Kansas City, KS 2JCO, LLC, Wichita, KS Notice of Forfeiture 2JFK, LLC, Wichita, KS 2JK, LLC, Overland Park, KS In accordance with Kansas statutes, the following busi- 2M, LLC, Dodge City, KS ness entities organized under the laws of Kansas and the 2nd Chance Lawn and Landscape, LLC, Wichita, KS foreign business entities authorized to do business in 2nd to None, LLC, Wichita, KS 2nd 2 None, LLC, Wichita, KS Kansas were forfeited during the month of October 2020 2shutterbugs, LLC, Frontenac, KS for failure to timely file an annual report and pay the an- 2U Farms, L.L.C., Oberlin, KS nual report fee. 2u4less, LLC, Frontenac, KS Please Note: The following list represents business en- 20 Angel 15, LLC, Westmoreland, KS tities forfeited in October. Any business entity listed may 2000 S 10th St, LLC, Leawood, KS 2007 Golden Tigers, LLC, Wichita, KS have filed for reinstatement and be considered in good 21/127, L.C., Wichita, KS standing. To check the status of a business entity go to the 21st Street Metal Recycling, LLC, Wichita, KS Kansas Business Center’s Business Entity Search Station at 210 Lecato Ventures, LLC, Mullica Hill, NJ https://www.kansas.gov/bess/flow/main?execution=e2s4 2111 Property, L.L.C., Lawrence, KS 21650 S Main, LLC, Colorado Springs, CO (select Business Entity Database) or contact the Business 217 Media, LLC, Hays, KS Services Division at 785-296-4564. -

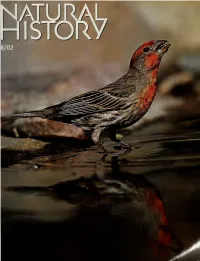

AMNH Digital Library

^^<e?& THERE ARE THOSE WHO DO. AND THOSE WHO WOULDACOULDASHOULDA. Which one are you? If you're the kind of person who's willing to put it all on the line to pursue your goal, there's AIG. The organization with more ways to manage risk and more financial solutions than anyone else. Everything from business insurance for growing companies to travel-accident coverage to retirement savings plans. All to help you act boldly in business and in life. So the next time you're facing an uphill challenge, contact AIG. THE GREATEST RISK IS NOT TAKING ONE: AIG INSURANCE, FINANCIAL SERVICES AND THE FREEDOM TO DARE. Insurance and services provided by members of American International Group, Inc.. 70 Pine Street, Dept. A, New York, NY 10270. vww.aig.com TODAY TOMORROW TOYOTA Each year Toyota builds more than one million vehicles in North America. This means that we use a lot of resources — steel, aluminum, and plastics, for instance. But at Toyota, large scale manufacturing doesn't mean large scale waste. In 1992 we introduced our Global Earth Charter to promote environmental responsibility throughout our operations. And in North America it is already reaping significant benefits. We recycle 376 million pounds of steel annually, and aggressive recycling programs keep 18 million pounds of other scrap materials from landfills. Of course, no one ever said that looking after the Earth's resources is easy. But as we continue to strive for greener ways to do business, there's one thing we're definitely not wasting. And that's time. www.toyota.com/tomorrow ©2001 JUNE 2002 VOLUME 111 NUMBER 5 FEATURES AVIAN QUICK-CHANGE ARTISTS How do house finches thrive in so many environments? By reshaping themselves. -

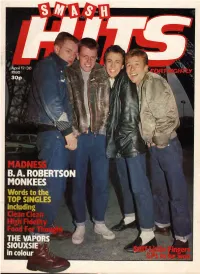

Smash Hits Volume 33

FORTNIGHTLY March 6-19 1980 i: fcMrstfjg i TH LYING LIZARDS .;! albums STS EDMUNDS )ur GRRk/£V£t/HlfLK HATES 7EEJM THAT TVf^ itav UGLYMONSTERS/ ^A \ / ^ / AAGHi. IF THERE'S ONE THING THATMAKES HULK REALLYAM6RY, IT'S PEOPLE WHO DON'T LOOK AFTER THEIRT€€TH! HULK GOES MAD UNLESS PEOPLE CLEAN THEIR TEETH THOROUGHLY EVERY DAY (ESPECIALLY LAST THING ATNIGHT). HE GOES SSRSfRK IFTHEY DON'T VISITTHE DENTIST REGULARLY! IF YOU D0N7 LOOKAFTER YOUR TEETH, SOMEBODY MAY COME BURSTING INTO YOUR HOUSE IN A TERRIBLE TEMPER AND IT WON'T BE THE MamAM...... 1 ! IF YOU WOULD LIKE A FREE COLOUR POSTER COPY OF THIS ADVERTISEMENT, FlU IN THE COUPON AND RETURN IT TO: HULK POSTER P.O BOX 1, SUDBURY, SUFFOLK COlO 6SL. tAeE(PUASETICKTHEAPPROPRIATEBOir)UNDERI3\Z\i3-l7\3lSANDOVER\JOFFERCLOSESONAPRIL30THmO.AUOW2SDAYSFORDELIVERY(sioaMPmisniA5l}l SH 1 uNAME ADDRESS X. i ^i J4 > March 6-19 1980 Vol 2 No. 5 Phew! Talk about moving ANIMATION mountains — we must have The Skids 4 shifted about six Everests' worth of paper this fortnight, what with ALABAMA SONG your voting forms and Walt David Bowie 4 Jabsco entries. With a bit of luck we'll have the poll results ready SPACE ODDITY forthe next issue but you'll find David Bowie 5 our Jabsco winners on page 26 of this issue. There's also an CUBA incredibly generous Ska Gibson Brothers 8 competition on page 24, not to mention our BIG NEWS! Turn to ALL NIGHT LONG the inside back page and find out Rainbow 14 what we mean . I'VE DONE EVERYTHING FOR YOU Sammy Hagar 14 Managing Editor HOT DOG Nick Logan Shakin' Stevens 17 Editor HOLDIN' -

The Damned Don't You Wish Press Release.Indd

PRESS RELEASE The Damned: Don’t You Wish That We Were Dead (15) RELEASE DATE On Blu-ray and DVD 29 May 2017 On Digital 22 May 2017 KEY TALENT INFORMATION Starring • David Vanian (lead singer, The Damned) • Captain Sensible (guitar/vocals, The Never mind the Sex Pistols… Damned) • Rat Scabies (drummer, The Damned) here’s The Damned! • Lemmy (Motorhead) • Mick Jones (The Clash) Fast Sell: • Steve Diggle (The Buzzcocks) • Chrissie Hynde (The Pretenders) A rip-roaring, hellraising account of one of the fi rst and • Chris Stein and Clem Burke (Blondie) greatest punk bands, The Damned, who ripped up the • Jon Moss (Culture Club) 70s music scene, fell apart in chaos, reformed and are still • Duff McKagan (Guns ‘N’ Roses) touring today 40 years strong! This joins Lemmy, The Filth • Glen Matlock (Sex Pistols) and the Fury and Anvil as a gleefully riotous, must watch • Nick Mason (Pink Floyd) rock-doc! • Ian MacKaye (Fugazi, Minor Threat) • Jesse Hughes (Eagles of Death Metal) From the co-director of Lemmy, featuring Chrissie Hynde, • Dexter Holland (The Off spring) Mick Jones, Lemmy, and members of Pink Floyd, Black Flag, • Jack Grisham (T.S.O.L) Guns ‘N’ Roses, Sex Pistols, Fugazi, Blondie, The Buzzcocks • David Gahan (Depeche Mode) and many more! • Don Letts • Billy Idol Synopsis: Director The story of the long-ignored pioneers of punk: The • Wes Orshoski (Lemmy) Damned. CONTACT/ORDER MEDIA The long-ignored pioneers of punk, The Damned started out as trailblazers on London’s 70s punk rock scene, being Thomas Hewson - [email protected] the fi rst British punk band to release a single, the immortal New Rose in 1976. -

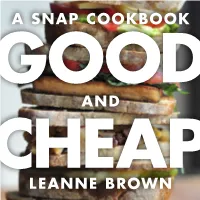

Good and Cheap – a SNAP Cookbook by Leanne Brown

A SNAP COOKBOOK GOOD AND CHEap LEANNE BROWN Introduction ....................5 Salad ...............................................28 Broiled Eggplant Salad ....................................29 Kale Salad ......................................................30 Taco Salad ......................................................32 Text, recipes, design, Beet and Chickpea Salad ................................33 and photographs by Tips .......................................................6 Cold and Spicy Noodles ..................................34 Leanne Brown, in Apple-Broccoli Salad .......................................36 fulfillment of a final project for a master’s degree in food studies at New York University. Pantry Basics .................8 Soup ..................................................37 I am indebted to Corn Soup .....................................................38 other cooks whose Butternut Squash Soup ..................................40 recipes have guided Dal ................................................................42 me, and all those Methods .....................................9 friends, professors, and classmates who supported me. Snacks and Small This book is distributed Staples .........................................10 under a Creative Tortillas .........................................................11 Bites ..................................................43 Commons Attribution Rotis ..............................................................12 IDEAS Yogurt Smash! ..................................... -

HALF PRICE HALF €24 .99 PRICE Was €49.99 €17 .49 Was €34.99 Super Tailspin See Page Tigger * 6

2010 Autumn / Winter Catalogue See page Singing Orchestra * 20 HALF PRICE HALF €24 .99 PRICE was €49.99 €17 .49 was €34.99 Super Tailspin See page Tigger * 6 See Scalextric Micro page HALF 21 Rally Masters * PRICE Sleepy €39 .99 Igglepiggle * was €79.99 HALF See PRICE page 69 €24 .99 was €49.99 See Take Along page HALF 31 PRICE Police Station * €29 .99 was €59.99 HALF See PRICE page Fairy-Tastic 42 Princess * €10 .99 was €21.99 * While stocks last REAL VALUE from a REAL TOYSHOP Welcome to the 2010 Toymaster Autumn/Winter catalogue Toymaster is a national association of locally owned specialist toy shops who combine to bring you real service and real value. This catalogue off ers just a small selection of our huge range of your children’s favourite toys. Our prices are always competitive and our friendly, knowledgeable staff are on hand to help and advise. We hope that you enjoy looking through this year’s catalogue and we look forward to welcoming you at your local Toymaster store very soon. The items illustrated in this catalogue are subject to availability and may not be carried by all Toymaster stores. All sizes quoted are approximate. The prices shown in this catalogue only apply in the store(s) listed on the reverse. Where higher prices are quoted, these have been charged at selected Toymaster outlets for at least 28 days in the preceding 6 months. Prices are applicable until 30th November 2010, subject to circumstances beyond our control. (Please be aware that all retail prices do not include any EMC charges). -

Smash Hits Volume 36

4pril 17-30 ^ 1980 m 30p 1 4. \ t, i% \ '."^.iiam 1 \ # »^» r ,:?^ ) ^ MARNF B. A. ROBERTSON NONKEES THE originals/ The Atlantic Masters — original soul music from the Atlantic label. Ten seven inch E.P.s, each with four tracks and at least two different artists. Taken direct from the original master tapes. Re-cut, Re-issued, Re-packaged. £1.60^ 11168 2 SMASH HITS April 17-30 1980 Vol 2 No. 8 WILL I HOLD IT right there! Now before WHAT DO WITHOUT YOU? you all write in saying how come Lene Lovich 4 there's only four of Madness on CLEAN CLEAN the cover, we'll tell ya. That heap of metalwork in the background The Buggies 5 IS none other than the Eiffel DAYDREAM BELIEVER Tower and the other trois {that's i'our actual French) scarpered off The Monkees 7 up it instead of having their photo MODERN GIRL taken. Now you know why Sheena Easton 8 they're called Madness! More nuttiness can be found on pages SILVER DREAM RACER 12 and 13, and other goodies in David Essex 14 this issue include another chance to win a mini-TV on the I'VE NEVER BEEN IN LOVE crossword, a binder offer for all Suzi Quatro 15 your back issues of Smash Hits CHECK OUT THE GROOVE (page 36), another token towards Mandging Editor your free set of badges (page 35) Nick Logan Bobby Thurston 19 and our great Joe Jackson SEXY EYES competition featuring a chance to Editor himself! (That's Dr. Hook 22 meet the man on Ian Cranna page 28). -

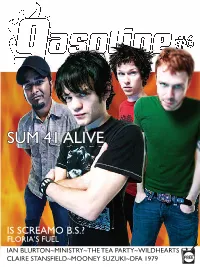

Sum 41 Alive

SSUMUM 4411 AALIVELIVE IS SCREAMO B.S.? FLORIA’S FUEL IAN BLURTON~MINISTRY~THE TEA PARTY~WILDHEARTS CLAIRE STANSFIELD~MOONEY SUZUKI~DFA 1979 THE JERRY CAN The summer is the season of rock. Tours roll across the coun- try like mobile homes in a Florida hurricane. The most memo- rable for this magazine/bar owner were the Warped Tour and Wakestock, where such bands as Bad Religion, Billy Talent, Alexisonfire, Closet Monster, The Trews and Crowned King had audiences in mosh-pit frenzies. At Wakestock, in Wasaga Beach, Ont., Gasoline, Fox Racing, and Bluenotes rocked so hard at their two-day private cottage party that local authorities shut down the stage after Magneta Lane and Flashlight Brown. Poor Moneen didn't get to crush the eardrums of the drunken revellers. That was day one! Day two was an even bigger party with the live music again shut down. The Reason, Moneen and Crowned King owned the patio until Alexisonfire and their crew rolled into party. Gasoline would also like to thank Chuck (see cover story) and other UN officials for making sure that the boys in Sum41 made it back to the Bovine for another cocktail, despite the nearby mortar and gunfire during their Warchild excursion. Nice job. Darryl Fine Editor-in-Chief CONTENTS 6 Lowdown News 8 Ian Blurton and C’mon – by Keith Carman 10 Sum41 – by Karen Bliss 14 Floria Sigismondi – by Nick Krewen 16 Alexisonfire and “screamo” – by Karen Bliss 18 Smash it up – photos by Paula Wilson 20 Whiskey and Rock – by Seth Fenn 22 Claire Stansfield – by Karen Bliss 24 Tea Party – by Mitch Joel -

Razorcake Issue #25 As A

ot too long ago, I went to visit some relatives back in Radon, the Bassholes, or Teengenerate, during every spare moment of Alabama. At first, everybody just asked me how I was my time, even at 3 A.M., was often the only thing that made me feel N doing, how I liked it out in California, why I’m not mar- like I could make something positive out of my life and not just spend N it mopping floors. ried yet, that sort of thing. You know, just the usual small talk ques- tions that people feel compelled to ask, not because they’re really For a long time, records, particularly punk rock records, were my interested but because they’ll feel rude if they don’t. Later on in the only tether to any semblance of hope. Growing up, I was always out of day, my aunt started talking to me about Razorcake, and at one point place even among people who were sort of into the same things as me. she asked me if I got benefits. It’s probably a pretty lame thing to say, but sitting in my room listen- I figured that it was pretty safe to assume that she didn’t mean free ing to Dillinger Four or Panthro UK United 13 was probably the only records and the occasional pizza. “You mean like health insurance?” time that I ever felt like I wasn’t alone. “Yeah,” she said. “Paid vacation, sick days, all that stuff. But listening to music is kind of an abstract. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

Language Relationships. the Net Three Chapters Focus On

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 204 794 CS 206 501 AUTHOR Kroll, Barry M.,, rd.: Vann, Roberta J., Ed. TTTLE Exploring Speaking-Writing Pelationships: Connections and Contrasts. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. DEPORT NO ISBN-0-8101-1609-3 PUB DATE 91 NOTE 247p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Pd., Urbana, IL 61801(Stock No. 16493, $9.95 member, $12.45 non-member). BOBS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Developmental Stages: English (Second Language) : Hearing Impairments: *Language Acquisition: Literature Reviews: *Oral Language; *Relationship: *Research Methodology: Social vnvironment: *Speech Communication: speech Skills: *Teaching Methods: *writing (Composition): Writing Skills: Written Language ABSTRACT The 13 chapters \in this volume explore what is known and what still needs to be learned about the complex relationships between speaking and writing. The',first chapter in thebook provides a detailed overview of linguistic studies of oral and written language relationships. The net three chapters focuson the relationships between children,os oral and written language skillsand what these relationships imply about the teaching of writingand reading. Chapters five and six consider oral and written'language in a societal context, while chapters seven, eight, and nineare concerned with methodological issues in the study of speaking-writing telatiorships, each suggestira a way to broaden the understandingof these relationships. The next, two chapters broaden the understanding of oral-written relationships\by considering two specialgroups of dividuals who often struggle\ to learn English--speakers of other languages, and the profoundly deaf. The final two chapters focuson pedagogy, such as integrating speaking and writing ina business communications course. -

Virus 23, 1989

Contents Replicating New Strains Page 4 Jonathan Levine Interview By Bruce Fletcher Page 5 . ,A Toxic G,uide .from Greenpeace Page 15 Brain machines By Belinda Atkinson Page 22 William Gibson biography By Tom Maddox Page 24 ZING, ZANG A Comic from Brad Lambert Page 26 William Gibson Interview By Darren Wershler Henry Page 28 The Two Sides of Tom Maddox By Bruce Fletcher Page 36 Now I Lay Me .. Down To Sleep Fiction by Bruce Fletcher Page 40 Molester A poem by Yassin 80ga Page 44 Frank Ogden: Laws of the Future Page 45 Television Magick By T. o. P.Y. U.S. Page 48 The A.D.'o.S.A. recommends Page 58 Clippings Page 64 Virus 23, 1989. C\O BOX 46 G)Share-Right 1989 RED DEER, ALBERTA, You may reproduce this material if your recipients may also reproduce it. CANADA. T4N 5E7. Front cover: Video-Head - Donald David. PAGE4 VIRUS 23, ISSUE 0 eplicating new Reality begins with the human mind. The human nervous system filters, categorizes and distorts the external universe until the individual can truly be said to create the world in which they live. The process of enculturation by itself usually creates the reality in which most people live. Thought is imposed by the cultural environment. Values, beliefs and even behavioral paradigms are detcnnincd by the social status quo. People live in a shared illusory reality, a consensual hallucination, without realizing its true nature, thereby abscond ing themselves of all personal responsibility. They believe they know truth. Individuals have the potent.ial to control these illusions, foster individual thought and promote rapid changes within the existing socio-cultural mileau.