The Silurian of Shropshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Cabinet, 18/10/2017 12:30

Shropshire Council Legal and Democratic Services Shirehall Abbey Foregate Shrewsbury SY2 6ND Date: Tuesday, 10 October 2017 Committee: Cabinet Date: Wednesday, 18 October 2017 Time: 12.30 pm Venue: Shrewsbury Room, Shirehall, Abbey Foregate, Shrewsbury, Shropshire, SY2 6ND You are requested to attend the above meeting. The Agenda is attached Claire Porter Head of Legal and Democratic Services (Monitoring Officer) Members of Cabinet Deputy Members of Cabinet Peter Nutting (Leader) Clare Aspinall Steve Charmley (Deputy Leader) Dean Carroll Joyce Barrow Rob Gittins Lezley Picton Roger Hughes David Minnery Elliott Lynch Robert Macey Alex Phillips Nic Laurens Nicholas Bardsley Lee Chapman Steve Davenport Your Committee Officer is: Jane Palmer Senior Democratic Services Officer Tel: 01743 257712 Email: [email protected] NOTICE RE VIDEO RECORDING OF CABINET MEETINGS & REQUIREMENTS OF DATA PROTECTION ACT 1998 Cabinet meetings are video recorded by Shropshire Council and these recordings will be made available to the public via the Shropshire Council Newsroom. Images of individuals may be potentially classed as ‘personal information’ and subject to the requirements of the Data Protection Act 1998. Members of the public making a recording of the meeting are advised to seek advice on their obligations to ensure any processing of personal information complies with the Data Protection Act. Meetings video recorded by Shropshire Council may be made available to the public via the Shropshire Newsroom, or generally on the internet or other -

Proceedings of the Shropshire Geological Society , 8, 1─2

ISSN 1750-855X (Print) ISSN 1750-8568 (Online) Proceedings of the Shropshire Geological Society No. 8 1989 Contents 1. Brenchley , P.: Ordovician sediments and palaeogeography ……..………………………... 1 2. McKerrow, S.: Silurian of Shropshire …………………………………………….………... 3 3. Jones, G.: Iceland ………………………………………………..………………………..… 6 4. Gibson, S.: Field Meeting Report: Fossil fish remains in the Devil’s Hole section, near Morville, 7 led by Maggie Rowlands and Peter Tarrant 10 th April 1988 ………………………………….. 5. Powell, A.: Field Meeting Report: ‘Ice and Fire’ field weekend in Snowdonia, led by Malcolm 12 Howells and Ken Addison 14th -15 th May 1988 ..……………….…………………………….. 6. Gibson, S.: Field Meeting Report: Ordovician rocks of South Shropshire, led by Bill Dean 12th 16 June 1988 .…………………………………………………………………………………… 7. Gibson, S.: Field Meeting Report: The Talyllyn Valley, led by Warren Pratt 17th July 1988 …... 19 8. Henthorn, D.: Field Meeting Report: The Carboniferous of South Wales, led by Sue Gibson 18th 21 September 1988 …………………………………………………………………………….... 9. Scholey, J. & Ingle, D.: The New Studley Tunnel …………...………………………………… 24 10. Whittaker, A.: Deep Geology ─ Method and Results ………...………………………………… 27 11. Bradshaw, R.: Metamorphism ─ the process that turns ugly ducklings into swans ……………... 29 Available on-line: http://www.shropshiregeology.org.uk/SGSpublications Issued January 1989 Published by the Shropshire Geological Society ISSN 1750-855X (Print) ISSN 1750-8568 (Online) Ordovician sediments and palaeogeography 1 Pat Brenchley BRENCHLEY, P. (1989). -

Lower Westwood Farm Stetton Westwood, Much Wenlock, Shropshire, TF13 6DF

3 The Square Church Stretton Shropshire SY6 6DA www.samuelwood.co.uk . Lower Westwood Farm Stetton Westwood, Much Wenlock, Shropshire, TF13 6DF A substantial 3 Reception/4 Bedroomed Stone Farm House with a separate 2 Bedroomed Cottage. Set in a glorious location, with approximately 2 acres of grounds and useful outbuildings/stables and far-reaching views, at the end of a "no through" lane, yet only 2 miles from the centre of Much Wenlock. House EPC Rating E. Cottage EPC Rating E. Guide Price £725,000 t: 01694 722723 e: [email protected] Lower Westwood Farm, Stretton Westwood, Much Wenlock, Shropshire, TF13 6DF Lower Westwood Farm Is a property the Agents have no Master Bedroom Suite With Large Dressing Area with fitted hesitation in recommending for a viewing. Situated approximately 2 wardrobes and radiator. Windows to front and rear, leading through miles from the thriving, medieval town of Much Wenlock with an to a most superb: excellent range of shops, schooling, public houses etc, yet located in a very quiet and peaceful position, surrounded by open fields. Bathroom With roll top claw and ball bath. Walk in shower with The Main House has delightful accommodation, briefly, of 3 glazed screen. WC and twin hand basins with cupboard under. Oak Reception Rooms with 4 Bedrooms, including a superb Master flooring and period radiator. Bedroom with Ensuite and Dressing Room. The separate cottage is . a lovely single storage barn conversion with a large Living Room, fitted Kitchen, Bathroom and 2 Bedrooms. This could be used for holiday accommodation or for a relative. -

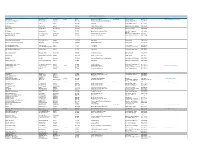

Placement Contact Lists from 2019

Placement Contact Lists FROM 2019 Placement Placement Address1 Placement Address 2 Town Postcode Occupational Area Type of Business Contact Telephone No. Email Address 3D Hair Studio 50 West Street St Georges Telford TF2 9 Hairdressers assistant Hairdressers Deborah Heaney 07813 712610 [email protected] 7 Sence Event Management The Town House Oswestry SY11 1AQ Business Admin/Professional Management Charlotte Gwynne (Event 01691 670027 Manager) 7 Valley Transport Unit 29 Shifnal TF11 8SD Transport Glenys Hillman - Owner 01952 461991 A H Griffiths 11 Bull Ring Ludlow SY8 1AD Retail / Customer Service Matthew Sylvester - Manager 01584 872141 A Ryan & Son 60 High Street Much Wenlock TF13 6AE Retail / Customer Service Sue Ryan - Manager 01952 727409 A T Browns Hortonwood 50 Telford TF1 7GZ Motor Vehicle & Associated Trade Dave Price - Operations 01952 605331 Manager A Walters Electrician Contractor 62 Longden Road Shrewsbury SY3 7HG Plant and Tool Hire/ Contractor Mike Davis- Operations Director 01743 247850 Aardvark Books Ltd The Bookery Bucknell SY7 0DH Retail / Customer Service Sarah Swinson (Director) 01547 530744 Abacus Day Nursery (Newport) 38 St Mary's Street Newport TF10 7AB Educational Leanne Nolan 01952 813652 Abbey Veterinary Centre (Shawbury) High Ridge Shrewsbury SY4 4NW Working With Animals Tracie Howells 01939 250655 ABC Day Nursery (Hadley) Crescent Road Telford TF1 5JU Educational Emma Burrows 01952 387190 ABC Day Nursery (Hoo Farm) Hoo Farm Animal kingdom, Telford TF6 6DJ Educational Lucy Holbrook - Manager 01952 -

Apr., Vol. 23 No. 1

I- - u .D a E ~ taJ %.. #,c ", C ., Col u fa ., E ~ 0 U taJ > ~ • . 0 0 a .- - 0 '"a- Col taJ -- .. .. '" Q, ~ -c E 0 .c taJ u I jQ % ~ ~ ~ d(iU. A Few Words from the Editors Greetings! It is a brilliantly sunny day in San Francisco. It's just past the Spring Equinox, most ofthe fruit trees have flowered, and our morris teams are madly learning dances and setting up gigs for May and June. A firring time [0 be typesetting a morris newslerrer, even if the main subject is the winter version! In this issue, as promised, we are publishing the typescripts from two of rhe rhree ralks given ar "Border Morris-Roors and Revival." This workshop was presented on February 29rh, 1992, bur rhe talks have nor been published before. Sreve Cunio, our contacr in the UK for these papers, has provided us with a descriprion of the workshop, which is on rhe nexr page. Roy Dommen's ralk did a lot ro ser rhe historical background of Border morris. We have added some annotarions (which appear in brackets), to clarifY a few acronyms, etc., thar may be obscure to Ameri can audiences, bur have otherwise left rhe rexr prerty much as ir was presented. He also showed some drawings of Border kirs, which we will nor reproduce here; if you are interesred, we suggesr you acquire Dave Jones' book, The Roots o/Welsh Border Morris. John Kirkparrick's piece bears some resemblance to his article, "Bor dering on the Insane," which we reprinted in the last AMN. -

A Study of Ballstone and the Associated Beds in the Wenlock

193 A STUDY OF BALLSTONE AND 'ToHE ASSOCI ATED BEDS IN THE WENLOCK LIME STONE OF SHROPSHIRE. By MISS M. C. CROSFIELD and MISS M. S. JOHNSTON. WITH NOTE ON SOME REEF-STRUCTURES IN GOTLAND. By F. A. BATHER, D.S., F.R.S. [Read March 61h, 1914.1 PAGE I.-Introduction 193 I I.-Historical Summar.y. • . • . 19+ IlL-General Description of the Wenlock Limestone of Shropshire and Herefordshire . 196 j V.-Description of dallrlouf .. 199 V.-Description 'of the Associated Beds . • 202 VI.-Selected Qua'lries and Faunal Notes. .•... 203 VIL-Comparison of the Wenlock Limestone of Wenlock Edge with that of other Areas in England ...•.. 210 VII I.-Comparison of Ballstone with Similar Structures in Pala-ozoic Limestones ... 212 IX.-Sllmm,iry.-Conclllsions. ... .. 22 I Appendix.-Note on Some Reef-Structures in Gotland . 225 I.-INTRODUCTION. HE Wenlock Limestone of Wenlock Edge and the adjoining T district is intimately known to most geologists, but there are certain features developed in these beds to which we would direct further attention. No geologist who has visited the region can have failed to notice the peculiar lenticular structure which the limestone assumes in certain parts. In an evenly-bedded limestone an irregular ball-shaped or lenticular mass of unstratified limestone is found to occur, which a closer inspection reveals to be crowded with fossils. This development of the limestone has received from the Shropshire quarrymen the name of ballstone. Ori our first visit our attention was at once arrested by these structures, and we have in consequence made a study of these beds with the hope of satisfying ourselves as to the causes which have produced them. -

INHIGEO Annual Record No

ISSN 1028-1533 International Commission on the History of Geological Sciences INHIGEO ANNUAL RECORD I No. 46 Covering activitiesI generally in 2013 Issued in 2014 INHIGEO is A Commission of the International Union of Geological Sciences & An affiliate of the International Union of the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology Compiled and Edited by Wolf Mayer INHIGEO Editor Printed in Canberra on request Available at www.inhigeo.org 1 | Page 2 | Page CONTENTS INHIGEO Annual Record No. 46 (Published in May 2014 covering events generally in 2013) INHIGEO BOARD 7 MESSAGES TO MEMBERS President‘s Message: Kenneth L. Taylor 8 Secretary-General‘s Report: Barry Cooper 9 Editor’s Message: Wolf Mayer 10 INHIGEO 2014 – Asilomar, California, United States 12 INHIGEO 2015 – Beijing 13 INHIGEO 2016 – Cape Town 13 LATER INHIGEO CONFERENCES 14 OTHER INHIGEO BUSINESS NOTICES Liaison with other IUGS Commissions and Task Groups 14 INHIGEO Affiliated Association category 15 INHIGEO Virtual Bibliography 16 A message encouraging INHIGEO members to join HESS 18 INHIGEO CONFERENCE AND EXCURSION REPORTS Report on the INHIGEO Meeting, Manchester, United Kingdom, 22-27 July 2013 19 Pre-congress Field Trip: The Silurian of ‘Siluria’ and the Idea of a Palaeozoic Era 24 Intra-congress trip: Buxton Spar and Buxton Spa 28 Post-congress fieldtrip: Ruskin’s Geology 30 International Congress of the History of Science, Technology and Medicine – Manchester 2013 34 MANCHESTER MANIFESTO 36 3 | Page OTHER CONFERENCE REPORTS Past, present and future of human connections to the Antarctic 37 CONFERENCES OF INTEREST The BSHS Annual Conference, 6 July 2014, at the University of St Andrews. -

Schedule of Appeals As at Committee 17 November 2020

Committee and date Southern Planning Committee 17 November 2020 SCHEDULE OF APPEALS AS AT COMMITTEE 17 NOVEMBER 2020 LPA reference 19/00860/VRA106 Appeal against Refusal Committee or Del. Decision Delegated Appellant Mr Tristan Ralph Proposal Variation of Section 106 for planning application number 13/01696/FUL Location The Old Chapel, Stretton Westwood, Much Wenlock Shropshire, TF13 6DF Date of appeal 19/08/2020 Appeal method Written representations Date site visit Date of appeal decision 14/10/2020 Costs awarded Appeal decision Dismissed LPA reference 18/03355/FUL Appeal against Refusal Committee or Del. Decision Committee Appellant Longville Arms Limited Proposal Change of use of former public house to residential (resubmission of 17/01687/FUL) Location Longville Arms, Longville In the Dale, Much Wenlock Shropshire TF13 6DT Date of appeal 25.08.2020 Appeal method Written representations Date site visit Date of appeal decision 16.10.20 Costs awarded Appeal decision Allowed Contact: Tim Rogers (01743) 258773 Planning Committee – 17 November 2020 Schedule of Appeals and Appeals Decisions LPA reference 19/04826/FUL Appeal against Refusal Committee or Del. Decision Delegated Appellant Mr John Williams Proposal Erection of two split level dwellings Location Proposed Residential Development Land South Of The Hawthorns, Orchard Lane, Hanwood, Shrewsbury, Shropshire Date of appeal 25.08.2020 Appeal method Written Representations Date site visit Date of appeal decision 16.10.20 Costs awarded Appeal decision Dismissed LPA reference 17/04421/FUL Appeal against Refusal Committee or Del. Decision Committee Appellant Mr Wiggin Proposal Erection of two detached dwellings with detached open fronted double garages Location Land East Of The School House, Hopton Cangeford Shropshire Date of appeal 20.02.20 Appeal method Written representations Date site visit Date of appeal decision 23.10.20 Costs awarded Appeal decision Dismissed LPA reference 20/02036/PMBPA Appeal against Refusal Committee or Del. -

Annual Report 2019

Strettons Area Community Wildlife Group Annual Report 2019 www.shropscwgs.org.uk [email protected] Strettons Area Community Wildlife Group Contents 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 1.1 Community Wildlife Groups (CWGs) .......................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Strettons Area Community Wildlife Group ................................................................................................ 3 2. Survey Activities and Results .................................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Butterflies ................................................................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Stretton Wetlands ...................................................................................................................................... 8 2.3 Crayfish Survey 2019 ................................................................................................................................ 10 2.4 Estimating the Red Grouse Population on The Long Mynd ..................................................................... 13 2.5 Curlews, Lapwings and Other Birds Survey .............................................................................................. 17 2.6 Swifts in the -

Ken Jones Local History Day Held at Coalbrookdale on 20 April 2013

TRANSACTIONS OF THE WREKIN LOCAL STUDIES FORUM 2013 Proceedings of the Ken Jones Local History Day held at Coalbrookdale on 20 April 2013 Wrekin Local Studies Forum TRANSACTIONS OF THE WREKIN LOCAL STUDIES FORUM 2013 Contents Editorial … … … … … … 2 Ken Jones, his life and work ~ John Powell … … 3 Holywell Lane revisited ~ Barrie Trinder … … 8 Methodism in Telford, with particular reference to Ken Jones ~ John Lenton … … 12 Coal to the Power Station: the role of the railway ~ Neil Clarke ... … 24 Copyright – WLSF and contributors Ken at the Friends of the Ironbridge Gorge Museum 40th anniversary celebrations at Blists Hill in 2009 EDITORIAL The Forum The Wrekin Local Studies Forum exists to bring together organisations and individuals interested in local studies in and around Telford & Wrekin. It is a fully constituted group that meets quarterly to share and receive information, expertise and resources and to plan joint ventures. There is currently a mailing list of over 30 contacts representing local history, family history and reminiscence groups, civic societies, museums, archives, libraries, colleges and the local authority, and of these 18 are active members. The Forum aims to promote and encourage local studies in the area by organising exhibitions, day events and conferences, working with other organisation to widen access to resources and publishing bi-annual leaflets to advertise the interests and meetings of member societies. The Transactions To further the aims of the Forum, the Transactions presents selected local studies papers resulting from talks given at member-societies’ meetings and day conferences and from research undertaken by individual members. This issue of the Transaction is devoted entirely to the proceedings of the Ken Jones Local History Day. -

International Commission on the History of Geological Sciences

ISSN 1028-1533 International Commission on the History of Geological Sciences INHIGEO ANNUAL RECORD I No. 46 Covering activitiesI generally in 2013 Issued in 2014 INHIGEO is A Commission of the International Union of Geological Sciences & An affiliate of the International Union of the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology Compiled and Edited by Wolf Mayer INHIGEO Editor Printed in Canberra on request Available at www.inhigeo.org 1 | P a g e INSIDE COVER (Please scroll down) 2 | P a g e CONTENTS INHIGEO Annual Record No. 46 (Published in May 2014 covering events generally in 2013) INHIGEO BOARD 7 MESSAGES TO MEMBERS President‘s Message: Kenneth L. Taylor 8 Secretary-General‘s Report: Barry Cooper 9 Editor’s Message: Wolf Mayer 10 INHIGEO 2014 – Asilomar, California, United States 12 INHIGEO 2015 – Beijing 13 INHIGEO 2016 – Cape Town 13 LATER INHIGEO CONFERENCES 14 OTHER INHIGEO BUSINESS NOTICES Liaison with other IUGS Commissions and Task Groups 14 INHIGEO Affiliated Association category 15 INHIGEO Virtual Bibliography 16 A message encouraging INHIGEO members to join HESS 18 INHIGEO CONFERENCE AND EXCURSION REPORTS Report on the INHIGEO Meeting, Manchester, United Kingdom, 22-27 July 2013 19 Pre-congress Field Trip: The Silurian of ‘Siluria’ and the Idea of a Palaeozoic Era 24 Intra-congress trip: Buxton Spar and Buxton Spa 28 Post-congress fieldtrip: Ruskin’s Geology 30 International Congress of the History of Science, Technology and Medicine – Manchester 2013 34 MANCHESTER MANIFESTO 36 3 | P a g e OTHER CONFERENCE REPORTS Past, present and future of human connections to the Antarctic 37 CONFERENCES OF INTEREST The BSHS Annual Conference, 6 July 2014, at the University of St Andrews. -

Business Rate Relief and Council Tax Discretionary Discount Policy

Appendix A 2018 Business Rate Relief and Council Tax Discretionary Discount Policy PHIL WEIR – REVENUES AND BENEFITS SERVICE MANAGER SHROPSHIRE COUNCIL | Revenues and Benefits Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………………………….……......2 Background Information…………………………………………………………………………….………..2 Discretionary Charitable Top-Up Relief…………………………………………….................................3 Guidance…………………………………………………………………………………………………….……….3 Community Amateur Sports Clubs……………………………………………………………….……...3 Charity Shops…………………………………………………………………………………………….………...3 Financial Implications………………………………………………………………………………….…….…3 Approved Relief in Shropshire…………………………………………………………………….……….3 Discretionary Relief for Charities…………………………………………………………………………….………4 Guidance………………………………………………………………………………………………………….….4 Financial Implications……………………………………………………………………………………….….4 Approved Relief in Shropshire………………………………………………………………………….….4 Sports Clubs…………………………………………………………………………………………………….…..5 Social Enterprises………………………………………………………………………………………………...5 Rural Discretionary Relief………………………………………………………………………………………………..6 Guidance……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..6 Financial Implications…………………………………………………………………………………………..6 Approved Relief in Shropshire……………………………………………………………………………..6 Hardship Relief…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………7 Financial Implications…………………………………………………………………………………………..7 Options………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..7 Local Discounts………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..7 Financial Implications…………………………………………………………………………………………..7