Ken Jones Local History Day Held at Coalbrookdale on 20 April 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ironstone Mines of Shropshire

ISSN 1750-855X (Print) ISSN 1750-8568 (Online) The ironstone mines of Shropshire 1 Ivor Brown BROWN, I.J. (1990). The ironstone mines of Shropshire. Proceedings of the Shropshire Geological Society , 9, 7– 9. Summary of a talk describing the occurrence of ironstone within Shropshire and the methods by which it was mined. 1affiliation: Member of the Shropshire Caving and Mining Club However, investigations are currently being made to assess the safety of these areas, as some voids BACKGROUND migrate to the surface and can be a hazard. Within Shropshire ironstone occurs in the Coal The aggregate thickness of workable seams Measures sequence, mostly as nodules or cakes in increased from 2.4 m at Broseley to 21.9 m at seams in shales. The nodules vary in size and Donnington. The main ironstones worked were the frequency, with the Pennystone nodules being up Chance Pennystone, the Transpennystone, the to half a metre across and 0.15 m thick. Blackstone, the Brickmeasure, the Ballstone, the Underlying these ironstone-bearing shales is the Yellowstone, the Blueflat, the Whiteflat, the Crawstone Sandstone in which ironstone is Pennystone, and the Crawstone. Lesser seams disseminated throughout the seam. This was the included the Dunearth, the Ragged Robins and the richest source of ore, being up to 40% iron, and Poor Robins. outcropped in the banks of the River Severn. In the ironstone boom about 1837 the Abraham Darby mined it and it was the first seam Coalbrookdale Company alone had 31 mines to be worked out as it was pursued by the early producing 50,000 tons. -

Six Parishes Newsletter

SIX PARISHES NEWSLETTER for St Giles’ Church. Badger St Milburga’s Church. Beckbury` St Andrew’s Church. Ryton Rector: Rev’d Keith Hodson tel 01952 750774 Email: [email protected] Web Site: www.churches.lichfield.anglican.org/shifnal/beckbury/ Rota of Services in the 6 Parishes – September 2013 Badger Beckbury Ryton Kemberton Stockton Sutton Sunday Maddock 9.30 am 9.30 am 8.15 am 11 am Sept 1st Communion Matins Communion Communion 9.30 am 11 am 11 am Sept 8th Matins Morning Matins 9.30 am Sept 15th Morning 11 am 6.30 pm 11 am Sept 22nd Harvest Evensong Morning 9.30 am 9.30 am 11 am 6.30 pm Sept 29th Matins Communion Harvest Evensong LT Abbreviation: KH = Revd Keith Hodson; TD = Tina Dalton; LT = Local Team; PRAYER OF THE MONTH Father God, we pray for our schools and colleges at the start of the new year. Give to teachers enthusiasm to teach, and give to pupils enthusiasm to learn Especially for those beginning at a new school or university this month. For Jesus sake. Amen Next Newsletter Contributions for next month’s newsletter to either – David Tooth at Havenside, Beckbury – 01952 750324. Email – [email protected] Or Ruth Ferguson at Tarltons, Beckbury – 01952 750267 not later than 14th of this month, please. FROM THE RECTORY Photo Martyn Farnell Dear Friends, I guess that many of us born in the 1950s had summer holidays “at the seaside”. I was brought up in Warwickshire which is about as far from seaside resorts as one can get. -

Crown & Anchor Vaults, Bishops Castle TBA 8.30PM Broseley

Bell & Talbot, Bridgnorth Ashleys Café Bar, Shrewsbury Full Circle Festival Sunday Afternoon Acoustics with DJ Bex 9PM Secret Location within the Hills BBC Shropshire Introducing Charlie Grass 3PM-5PM Bull Inn, Shrewsbury (near to Presteigne) 96.0FM 8PM 8PM Tim Barret Evening Session 9PM The Essentials Moishes Bagel, The Destroyers, Dun Cow, Shrewsbury Cooper & Davis My Baby, Lori campbell, The Harp Hotel, Albrighton Indie Doghouse Festival Drayton Centre, Market Drayton Harp Hotel, Albrighton Housmans, Church Stretton Crown & Anchor Vaults, Bishops Castle Remi Harris Trio, Black Rapids & Anchor Inn, Shrewsbury Apex Jazz & Swing Band 1PM Bell & Talbot, Bridgnorth Hole In The Wall, Shrewsbury The Henry Girls 7.45PM £12.50 Jack Cotterill 8.30PM Dan Walsh 8PM Open Jam 8.30PM Little Rumba, Your Dad, Company My Left Foot 9PM Diamond Geezers 9PM The Rainbreakers EP launch + Two Faced Fighting Cocks, Stottesdon nr Bridgnorth of Fools, Little Loon and Cloudier Boars Head, Shrewsbury The Friars, Bridgnorth Tom & The Bootleg Beatles 9PM Sunday Session Open Mic 5PM The Shakespear, Newport White Lion, Bridgnorth Bull Inn, Shrewsbury Boat Inn, Jackfield nr Ironbridge Skies + many more entertainers. Stage 2 9PM Wayne Martin Blues Band 9.30PM Loggerheads, Shrewsbury The Friars, Bridgnorth Open Mic 8PM Bridgnorth Folk Night 8.30PM Open Mic Irish Music Night 8PM Midday - Midnight Britannia Inn, Shrewsbury The George, Bridgnorth Reid, Smith & Jones 9PM Robin Taylor 7PM Wheatsheaf, High Street Shrewsbury Eighty Six’d, ironbridge Adults £30 / 5-14yrs £15 -

Welcome to the Telford T50 50 Mile Trail

WELCOME TO THE TELFORD T50 50 MILE TRAIL This new 50 mile circular walking route was created in 2018 to celebrate Telford’s 50th anniversary as a New Town. It uses existing footpaths, tracks and quiet roads to form one continuous trail through the many different communities, beautiful green spaces and heritage sites that make Telford special. The Telford T50 50 Mile Trail showcases many local parks, nature reserves, woods, A 50 MILE TRAIL FOR EVERYONE TO ENJOY pools and open spaces. It features our history and rich industrial heritage. We expect people will want to explore this Fifty years ago, Telford’s Development Plan wonderful new route by starting from the set out to preserve a precious legacy of green space closest to where they live. green networks and heritage sites and allow old industrial areas to be reclaimed by wild The route is waymarked throughout with nature. This walk celebrates that vision of a magenta 'Telford 50th Anniversary' logo. interesting and very special places left for everyone to enjoy. The Trail was developed The Trail begins in Telford Town Park, goes by volunteers from Wellington Walkers are down to Coalport and Ironbridge then on Welcome, the Long Distance Walkers through Little Wenlock to The Wrekin, that Association, Walking for Health Telford & marvellous Shropshire landmark. It then Wrekin, Ironbridge Gorge Walking Festival continues over The Ercall nature reserve and Telford & East Shropshire Ramblers. through Wellington, Horsehay and Oakengates to Lilleshall, where you can www.telfordt5050miletrail.org.uk walk to Newport via The Hutchison Way. After Lilleshall it goes through more areas of important industrial heritage, Granville Country Park and back to The Town Centre. -

The National Way Point Rally Handbook

75th Anniversary National Way Point Rally The Way Point Handbook 2021 Issue 1.4 Contents Introduction, rules and the photographic competition 3 Anglian Area Way Points 7 North East Area Way Points 18 North Midlands Way Points 28 North West Area Way Points 36 Scotland Area Way Points 51 South East Way Points 58 South Midlands Way Points 67 South West Way Points 80 Wales Area Way Points 92 Close 99 75th Anniversary - National Way Point Rally (Issue 1.4) Introduction, rules including how to claim way points Introduction • This booklet represents the combined • We should remain mindful of guidance efforts of over 80 sections in suggesting at all times, checking we comply with on places for us all to visit on bikes. Many going and changing national and local thanks to them for their work in doing rules, for the start, the journey and the this destination when visiting Way Points • Unlike in normal years we have • This booklet is sized at A4 to aid compiled it in hope that all the location printing, page numbers aligned to the will be open as they have previously pdf pages been – we are sorry if they are not but • It is suggested you read the booklet on please do not blame us, blame Covid screen and only print out a few if any • This VMCC 75th Anniversary event is pages out designed to be run under national covid rules that may still in place We hope you enjoy some fine rides during this summer. Best wishes from the Area Reps 75th Anniversary - National Way Point Rally (Issue 1.4) Introduction, rules including how to claim way points General -

Shifnal Crime

SHIFNAL CRIME Rural Watch – East Shropshire .Rural News from around the Patch A full and thorough investigation is underway following an armed robbery at a bank in Madeley, Telford this afternoon (Monday 20 March) The offence happened at approximately 3pm when a person, entered Lloyd's Bank on the High Street in Madeley. The individual produced what appeared to be a gun, although whether it was real or an imitation gun is unknown, and demanded money before leaving on foot. Nobody was injured in the incident and witnesses and staff have been provided initial support by the investigating officers. The suspect is described as medium build and approximately 5'10" tall. They were dressed all in dark clothing but believed to be wearing black and white trainers. The suspect was carrying a black holdall and they had their face covered during the offence. Superintendent Tom Harding said: "We understand that this crime will be very concerning to the local community and I would reassure you that such a crime is unusual for the Telford area. We will have additional patrols in the Madeley area for the next few days to offer support to the community and identify any further witnesses. I have allocated a significant number of officers to this investigation to ensure we identify and arrest the suspect as soon as possible. To assist us in this I would ask that, as this was a busy time of day in the centre of the town, that anyone who has seen anything suspicious in around the High-Street area this afternoon, or has any other information relating to this serious offence, please call West Mercia Police on 101 quoting incident number 411s of 20 March. -

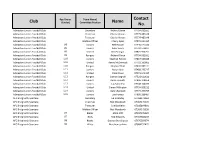

Team and Contact List

Age Group Team Name/ Contact Club Name (Under) Committee Position No. Admaston Juniors Football Club Secretary Richard Owen 07794 932661 Admaston Juniors Football Club Chairman Charlie Viccars 07779 485149 Admaston Juniors Football Club Treasurer Charlie Viccars 07779 485149 Admaston Juniors Football Club Welfare Officer Cherry Syass 07875 521364 Admaston Juniors Football Club U8 Juniors Neil Harper 07446 947335 Admaston Juniors Football Club U9 Juniors Peter Lewis 07794 576877 Admaston Juniors Football Club U9 United Ben Stringer 07825 912251 Admaston Juniors Football Club U9 Rangers Richard Owen 07794 932661 Admaston Juniors Football Club U10 Juniors Stephen Pollock 07817 563665 Admaston Juniors Football Club U10 United Kenny McDermott 07793 160005 Admaston Juniors Football Club U10 Rangers Clayton Elliott 07833 087111 Admaston Juniors Football Club U11 Juniors Aaron Hale 07488 233717 Admaston Juniors Football Club U11 United Dale Oliver 07971 543427 Admaston Juniors Football Club U11 Rangers Damon Bagnall 07521 620610 Admaston Juniors Football Club U12 Juniors Jamie Howells 07496 178659 Admaston Juniors Football Club U13 Juniors Jay Sahadew 07748 144076 Admaston Juniors Football Club U13 United Simon Millington 07734 858212 Admaston Juniors Football Club U14 Juniors Gary Chadwick 07779 299754 Admaston Juniors Football Club U15 Juniors Lee Harvey 07890 388467 AFC Bridgnorth Spartans Secretary Ed Hobbday 07968273163 AFC Bridgnorth Spartans Chairman Rob Woodcock 07984149999 AFC Bridgnorth Spartans Treasurer Sue Boadella 07815804601 AFC Bridgnorth Spartans Welfare Officer Rob Woodcock 07984149999 AFC Bridgnorth Spartans U7 Blacks Mark Clift 07817195029 AFC Bridgnorth Spartans U7 Reds Rob Edwards 07557383259 AFC Bridgnorth Spartans U8 Blacks Duncan Brassington 07970283674 AFC Bridgnorth Spartans U8 White Matthew Jenkins 07884252425 Age Group Team Name/ Contact Club Name (Under) Committee Position No. -

Six Parishes Newsletter

SIX PARISHES NEWSLETTER for St Giles’ Church. Badger St Milburga’s Church. Beckbury St Andrew’s Church. Ryton Rector: Rev’d Keith Hodson tel 01952 750774 Email: [email protected] Web Site: http://www.beckburygroupministry.org.uk Rota of Services in the 6 Parishes – October 2016 Badger Beckbury Ryton Kemberton Stockton Sutton Sunday Maddock 9.30am 9.30am 11am 6.30pm Oct 2nd Communion Morning Communion Evening KH (trad) Worship KH (new) Worship TD LT 9.30am 3pm 11am Oct 9th Communion Pets Service Harvest KH (trad) KH KH 9.30am 6.30pm 11am Oct 16th Matins Evensong Harvest KH KH KH 9.30am 5pm 11am 11am Oct 23rd Matins Evensong Morning Morning KH 1662 Worship Worship KH KH TD 10.30am Oct 30th All Saints KH KH - Revd Keith Hodson; TD - Tina Dalton; LT - Local Team PRAYER OF THE MONTH God, whose farm is all creation, take the gratitude we give. Take the finest of our harvest, crops we grow that we may live. Amen Contributions for next month’s newsletter to either – David Tooth at Havenside, Beckbury – 01952 750324. Email - [email protected] Or Ruth Ferguson at Tarltons, Beckbury – 01952 750267 not later than 14th of this month, please. FROM THE RECTORY Dear friends, The fields in our countryside show that harvest is nearly finished, with some fields left with stubble, some ploughed, while one or two have the new green growth of autumn sown cereals. We are in our harvest season at the local churches: one thanksgiving service already at Beckbury, and Stockton and Sutton Maddock in October. -

Ton Constantine, Shrewsbury, SY5 6RD

3 Lower Longwood Cottages, Eaton Constantine, Shrewsbury, SY5 6RD 3 Lower Longwood Cottages a semi- detached property situated just outside Eaton Constantine with stunning views of the landscape. It has two bedrooms, one reception room, kitchen and bathroom. Externally there is large lawned garden and off-road parking. The property is available to let now. Viewings by appointment with the Estate Office only and can be conducted in person or by video. Semi- Detached Off Road Parking Two Bedrooms Available immediately One Reception Room Large Garden To Let: £695 per Calendar Month reasons unconnected with the above, then your Situation and Amenities holding deposit will be returned within 7 days. Market Town of Shrewsbury 8 miles. New Town of Telford 10 miles. The Wrekin part of Insurance Shropshire Hills AONB 6 miles. Christ Church C Tenants are required to insure their own of E Primary, Cressage 3.5 miles. Buildwas contents. Academy 5 miles. Village shops within 5 miles and Shrewsbury and Telford offer supermarkets Smoking and chain stores. Wellington Train Station 8 Smoking is prohibited inside the property. miles, M54 motorway junction 5 miles. Please note all distances are approximate. Pets Pets shall not be kept at the property without the Description prior written consent of the landlord. All requests 3 Lower Longwood Cottages is a two bedroom will be considered and will be subject to separate semi-detached property with accommodation rental negotiation. briefly comprising of; Ground floor an entrance hallway, Bathroom including shower cubicle, Council Tax sink, heated towel rail and vinyl flooring, Kitchen For Council Tax purposes the property is banded which includes fitted wall and base units with B within the Shropshire County Council fitted worktops, tiled splashbacks, stainless steel authority. -

The Silurian of Shropshire

ISSN 1750-855X (Print) ISSN 1750-8568 (Online) The Silurian of Shropshire 1 Stuart McKerrow McKERROW, S. (1989). The Silurian of Shropshire. Proceedings of the Shropshire Geological Society , 8, 3─5. The account of a lecture describing the Silurian sediments, palaeoenvironments and stratigraphy of Shropshire. 1affiliation: Oxford University BACKGROUND EARLY SILURIAN Silurian rocks outcrop in Shropshire in an area In the Welsh Borderlands of Shropshire can be around the Shelve Inlier ─ west of the Longmynd seen the strongest effects of early Ashgill folding ─ and to the east of the Longmynd, an area and the late Ashgill drop in sea level, caused by running above and below Wenlock Edge. The water being entrapped at the polar caps. Ordovician rocks of the Shelve Inlier had been After this initial drop in sea level it rose again folded and have a parallel strike, whereas the world-wide and there is evidence of a gradual Silurian are flat-lying. spread of the sea from Wales across Shropshire If the contact between the Ordovician and into the Midlands during the Llandovery. As this Silurian sequences is traced towards the north- sea spreads we find evidence of various kinds of west it can be seen that the folding took place in fossil. The two most useful being graptolites in the early Ashgill. Also, just as the Longmynd the deep water and brachiopods in shallower plateau stands out today as a feature, so it water. probably did in former times also, at least during Graptolites are very useful as they show rapid the early Silurian: the Llandovery. -

B4380 Buildwas Speed Management Feasibility Report March 2017

B4380 Buildwas Speed Management Feasibility Report March 2017 Report Reference: 1076162 Prepared by: 2nd Floor, Shirehall Abbey Foregate Shrewsbury SY2 6ND Contents 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 2 Site Description .................................................................................................... 2 3 Site Observations...………………….………………………………………………..…5 4 Personal Injury Collision (PIC) and Speed data…….……………………………..... 7 5 Conclusions and Recommendations..…………………………………………..……..8 Version Date Detail Prepared By Checked By Approved By March Issue Feasibility Report D Ross D Davies PF Williams 2017 This Report is presented to Shropshire Council in respect of the B4380 Buildwas Speed Management Feasibility Study and may not be used or relied on by any other person or by the client in relation to any other matters not covered specifically by the scope of this Report. Notwithstanding anything to the contrary contained in the report, Mouchel Limited is obliged to exercise reasonable skill, care and diligence in the performance of the services required by Shropshire Council and Mouchel Limited shall not be liable except to the extent that it has failed to exercise reasonable skill, care and diligence, and this report shall be read and construed accordingly. This report has been prepared by Mouchel Limited. No individual is personally liable in connection with the preparation of this Report. By receiving this Report and acting on it, the client or any other person accepts that no individual is personally liable whether in contract, tort, for breach of statutory duty or otherwise. 2 B4380 Buildwas Speed Management March 2017 1 Introduction 1.1 Buildwas village is situated on the B4380 road (between Shrewsbury and Ironbridge) close to its junction with the A4169 Ironbridge Bypass. -

History Notes Tileries, Caughley to Coalport Walks

Caughley China Works Broseley Tileries In 1772 Thomas Turner of Worcester came to Caughley Tile making in Broseley goes back along way, A 'tyle house' (kiln) was mentioned along with Ambrose Gallimore, a Staffordshire potter, as being on ‘priory land’ in 1545. High quality local clays were mined alongside to extend a factory that had been in existence there for coal and iron and by the C19th, and as cities grew there was a huge market for about 15 years. Known as the Salopian Porcelain bricks, roof and floor tiles. Said to have been established in 1760, in operation Manufactory the Caughley works made some of the from at least 1828, by 1838 the Broseley Tileries were the largest works in the finest examples of C18th English Porcelain, now highly Broseley and Jackfield area. By 1870 the firm produced tessellated and encaustic sought after by collectors. Turner used underglaze floor tiles as well as roof and plain floor tiles. Broseley Tileries were operated by printing to make tea and dessert sets and other wares. the Onions family until 1877 when they sold them to a new company, Broseley Printing from copperplate engravings enabled designs Tileries Co Ltd. Another works close by was the Dunge Brick and Tile Works , it to be mass produced at low cost by a ceramic transfer ceased manufacture in 1903. In 1889 the area's leading manufacturers of roof Look for the monument at process, alongside the expensive hand painted the site of the Caughley tiles, which for some years had been known by the generic name 'Broseley Tiles', porcelain.