An Evaluation of Digital Data from Virginia Archaeological Websites

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assistant Curator Job Description ……

Assistant Curator Job description ……. Background For over a century, the Whitechapel Gallery has premiered world-class artists from modern masters such as Pablo Picasso, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Frida Kahlo to contemporaries such as Sophie Calle, Lucien Freud, Sarah Lucas and Walid Raad. With beautiful galleries, exhibitions, artist commissions, collection displays, historic archives, education resources, inspiring art courses, dining room and bookshop, the newly expanded Gallery is open all year round, so there is always something free to see. The Gallery is a touchstone for contemporary art internationally, plays a central role in London’s cultural landscape and is pivotal to the continued growth of the world’s most vibrant contemporary art quarter. Exhibitions Department The Exhibitions Department realises the ambitious programme of temporary exhibitions and commissions, including the production of catalogues to accompany these events. In addition, the Department is closely involved with an MA in Curating Contemporary Art, taught jointly with London Metropolitan University. The Department consists of the Chief Curator, Curator and Head of MA Curatorial Studies, Curator, 3 x Assistant Curators, Assistant Curator – Special Projects, Archivist and Archive Curator, Head of Exhibition Design and Production, Gallery Manager and Installation Manager. Role The Assistant Curator works with a small and busy team on the realisation of projects with artists, lenders and arts institutions; delivering modern and contemporary exhibitions and commissions, including the organisation of transport and insurance; registrarial duties; and the production of catalogues. As a member of the exhibitions team, the Assistant Curator contributes ideas to the Gallery’s programme, is essential to the department's collegiate work environment and liaises with other internal departments and with the professional art world, in one of the most dynamic art environments in Europe. -

Fixing Historic Preservation: a Constructive Critique of “Significance”

Peer Reviewed Title: Fixing Historic Preservation: A Constructive Critique of "Significance" [Research and Debate] Journal Issue: Places, 16(1) Author: Mason, Randall Publication Date: 2004 Publication Info: Places Permalink: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/74q0j4j2 Acknowledgements: This article was originally produced in Places Journal. To subscribe, visit www.places-journal.org. For reprint information, contact [email protected]. Keywords: places, placemaking, architecture, environment, landscape, urban design, public realm, planning, design, research, debate, historic, preservation, contructive, critique, significance, Randall Mason Copyright Information: All rights reserved unless otherwise indicated. Contact the author or original publisher for any necessary permissions. eScholarship is not the copyright owner for deposited works. Learn more at http://www.escholarship.org/help_copyright.html#reuse eScholarship provides open access, scholarly publishing services to the University of California and delivers a dynamic research platform to scholars worldwide. Fixing Historic Preservation: A Constructive Critique of “Significance” Randall Mason The idea of “significance” is exceed- Second, once judgments are made projects that tell their particular sto- ingly important to the practice of about a site, its significance is regarded ries. The broadening of preservation historic preservation. In significance, as largely fixed. Such inertia needs to from its curatorial roots has been a preservationists pack all their theory, be overcome, and -

1. Introduction

This PDF is a simplified version of the original article published in Internet Archaeology. All links also go to the online version. Please cite this as: Nicholson, C., Fernandez, R. and Irwin, J. 2021 Digital Archaeological Data in the Wild West: the challenge of practising responsible digital data archiving and access in the United States, Internet Archaeology 58. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.58.22 Digital Archaeological Data in the Wild West: the challenge of practising responsible digital data archiving and access in the United States Christopher Nicholson, Rachel Fernandez and Jessica Irwin Summary Archaeology in the United States is conducted by a number of different sorts of entities under a variety of legal mandates that lack uniform standards for data archiving. The difficulty of accessing data from projects in which one was not directly involved indicates an apparent reluctance to archive raw data and supplemental information with digital repositories to be reused in the future. There is hope that additional legislation, guidelines from professional organisations, and educational efforts will change these practices. 1. Introduction Though we are well into the 21st century, responsible digital archiving of archaeological data in the United States is not common practice. Digital archiving of cultural resource management reports in State Historic Preservation Offices, where they are often available by request though perhaps at a cost, is common; however, digitally archiving the datasets and other supporting materials that went into the creation of those documents is not. Though a vocal minority advocates for responsible digital archiving practices (Kansa and Kansa 2013; 2018; Kansa et al. -

Federal Laws and Regulations Requiring Curation of Digital Archaeological Documents and Data

Federal Laws and Regulations Requiring Curation of Digital Archaeological Documents and Data Cultural Heritage Partners, PLLC Prepared for: Arizona State University October 25th, 2012 © 2012 Arizona State University. All rights reserved. This report by Cultural Heritage Partners, PLLC describes and analyzes federal requirements for the access to and long-term preservation of digital archaeological data. We conclude that the relevant federal laws, regulations, and policies mandate that digital archaeological data generated by federal agencies must be deposited in an appropriate repository with the capability of providing appropriate long-term digital curation and accessibility to qualified users. Federal Agency Responsibilities for Preservation and Access to Archaeological Records in Digital Form Federal requirements for appropriate management of archaeological data are set forth in the National Historic Preservation Act (“NHPA”), the Archaeological Resources Protection Act (“ARPA”), the regulations regarding curation of data promulgated pursuant to those statutes (36 C.F.R. 79), and the regulations promulgated by the National Archives and Records Administration (36 C.F.R. 1220.1-1220.20) that apply to all federal agencies. We discuss each of these authorities in turn. Statutory Authority: Maintenance of Archaeological Data Archaeological data can be generated from many sources, including investigations or studies undertaken for compliance with the NHPA, ARPA, and other environmental protection laws. The NHPA was adopted in 1966, and strongly -

Digital Preservation Workflows for Museum Imaging Environments

The 11th International Symposium on Virtual Reality, Archaeology and Cultural Heritage VAST (2010) A. Artusi, M. Joly, D. Pitzalis, G. Lucet, and A. Ribes (Editors) Digital preservation workflows for museum imaging environments Michael Ashley1 1 Cultural Heritage Imaging, San Francisco, California, USA From: Principles and Practices of Robust, Photography-based Digital Imaging Techniques for Museums. Contributors: Mark Mudge, Carla Schroer, Graeme Earl, Kirk Martinez, Hembo Pagi, Corey Toler-Franklin, Szymon Rusinkiewicz, Gianpaolo Palma, Melvin Wachowiak, Michael Ashley, Neffra Matthews, Tommy Noble, Matteo Dellepiane. Edited by Mark Mudge and Carla Schroer, Cultural Heritage Imaging. The 11th International Symposium on Virtual Reality, Archaeology and Cultural Heritage VAST (2010) A. Artusi, M. Joly, D. Pitzalis, G. Lucet, and A. Ribes (Editors) This is a pre-print copy of a paper that is currently under review. Please respect the intellectual property of the authors and the efforts of the publishers and reviewers until its publication. If you find any errors that need modification please contact the author at [email protected]. Meanwhile this pdf is distributed to interested readers under a Creative Commons 3.0 license. M. Ashley / Digital Preservation Workflows For Museum Imaging Environments Digital preservation workflows for museum imaging environments Michael Ashley1 1 Cultural Heritage Imaging, San Francisco, California, USA Abstract We discuss and demonstrate practical digital preservation frameworks that protect images throughout the entire production life-cycle. Using off the shelf and open source software coupled with a basic understanding of metadata, it is possible to produce and manage high value digital representations of physical objects that are born archive- ready and long-term sustainable. -

Introducticn Tc Ccnservoticn

introducticntc ccnservoticn UNITED NATTONSEDUCATIONA],, SCIEIilIIFTC AND CULTIJRALOROANIZATTOII AN INIRODUCTION TO CONSERYATIOI{ OF CULTURAT PROPMTY by Berr:ar"d M. Feilden Director of the Internatlonal Centre for the Preservatlon and Restoratlon of Cultural Property, Rome Aprll, L979 (cc-ig/ws/ttt+) - CONTENTS Page Preface 2 Acknowledgements Introduction 3 Chapter* I Introductory Concepts 6 Chapter II Cultural Property - Agents of Deterioration and Loss . 11 Chapter III The Principles of Conservation 21 Chapter IV The Conservation of Movable Property - Museums and Conservation . 29 Chapter V The Conservation of Historic Buildings and Urban Conservation 36 Conclusions ............... kk Appendix 1 Component Materials of Cultural Property . kj Appendix 2 Access of Water 53 Appendix 3 Intergovernmental and Non-Governmental International Agencies for Conservation 55 Appendix k The Conservator/Restorer: A Definition of the Profession .................. 6? Glossary 71 Selected Bibliography , 71*. AUTHOR'S PREFACE Some may say that the attempt to Introduce the whole subject of Conservation of Cultural Propety Is too ambitious, but actually someone has to undertake this task and it fell to my lot as Director of the International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cxiltural Property (ICCROM). An introduction to conservation such as this has difficulties in striking the right balance between all the disciplines involved. The writer is an architect and, therefore, a generalist having contact with both the arts and sciences. In such a rapidly developing field as conservation no written statement can be regarded as definite. This booklet should only be taken as a basis for further discussions. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In writing anything with such a wide scope as this booklet, any author needs help and constructive comments. -

Deaccessioning Done Right by Jennifer Holt, Curator, Will Rogers Memorial Museums, Claremore

technical bulletin Deaccessioning done right by Jennifer Holt, Curator, Will Rogers Memorial Museums, Claremore Oklahoma Museums eaccessioning is the process used to ered; private sales can be problematic due to Association Dremove permanently an object from a transparency and accountability issues. The Technical Bulletin #47 museum’s collection or to document the rea- use of all proceeds should comply with the Published January sons for an involuntary removal of an object professional ethics and the law. from such a collection. The deaccession- 2009 ing process is used only when accessioned Procedures should be developed along with objects are at issue. Deaccessioning should policies. Deaccession check lists should not be viewed as a routine way to manage follow policy parameters. The registrar/col- indiscriminate collecting. The first rule is lection manager/curator should oversee the Back issues of techni- careful, focused collecting. process and maintain permanent records of cal bulletins published all deaccessions. by the Oklahoma There are a number of reasons why a mu- seum may be prompted to consider deacces- Problems may arise with the deaccession of Museums Associa- sioning. The condition of the object may be an object. The title to the object may be in- tion are available free so bad that it threatens other objects in the complete. Restrictions may have been placed to members. For a collection. A collection may contain unneces- on deaccessioning the object when donated. complete list of tech- sary duplicates. These dupes take resources Other issues that may appear include pri- nical bulletin topics, that could be used for new objects. -

Selection in Web Archives: the Value of Archival Best Practices

WITTENBERG: SELECTION IN WEB ARCHIVES Selection in Web Archives: The Value of Archival Best Practices Jamie Wittenberg, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, United States of America Abstract: The abundance of valuable material available online has mobilized the development of preservation initiatives at collecting institutions that aim to capture and contextualize web content. Web archiving selection criteria are driven by the limitations inherent in harvesting technologies. Observing core archival principles like provenance and original order when establishing collection development policies for web content will help to ensure that archives continue to assure the authenticity of the materials they steward. Keywords: Web Archives; Archival Theory; Digital Libraries; Internet Content; Selection and Appraisal Introduction The abundance of valuable material available online has mobilized the development of preservation initiatives at collecting institutions that aim to capture and contextualize web content. Methodologies for web collection practices are institution and collection-specific. Among institutions charged with preserving cultural heritage, web archiving has become commonplace. However, the disparity between institutional selection and appraisal criteria reveals the absence of standardization for web archive establishment. The Australian web archive, for example, accessions content that it evaluates as having long-term research value. The Library of Congress web archive, represented by its Minerva team, established a collection -

GRIIDC Compendium of Online Data Management Training Resources

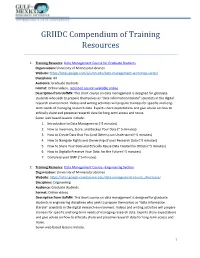

GRIIDC Compendium of Training Resources 1. Training Resource: Data Management Course for Graduate Students Organization: University of Minnesota Libraries Website: https://sites.google.com/a/umn.edu/data-management-workshop-series/ Disciplines: All Audience: Graduate students Format: Online videos, recorded session available online Description from UofMN: This short course on data management is designed for graduate students who seek to prepare themselves as “data information literate” scientists in the digital research environment. Videos and writing activities will prepare trainees for specific and long- term needs of managing research data. Experts share expectations and give advice on how to ethically share and preserve research data for long-term access and reuse. Seven web based lessons include: 1. Introduction to Data Management (~5 minutes) 2. How to Inventory, Store, and Backup Your Data (~ 5 minutes) 3. How to Create Data that You (and Others) can Understand (~5 minutes) 4. How to Navigate Rights and Ownership of your Research Data (~9 minutes) 5. How to Share Your Data and Ethically Reuse Data Created by Others (~5 minutes) 6. How to Digitally Preserve Your Data for the Future (~5 minutes) 7. Complete your DMP (~5 minutes) 2. Training Resource: Data Management Course –Engineering Section Organization: University of Minnesota Libraries Website: https://sites.google.com/a/umn.edu/data-management-course_structures/ Disciplines: Engineering Audience: Graduate students Format: Online videos Description from UofMN: This short course on data management is designed for graduate students in engineering disciplines who seek to prepare themselves as “data information literate” scientists in the digital research environment. Videos and writing activities will prepare trainees for specific and long-term needs of managing research data. -

August 2012, No. 44

In 2011, the project members took part in excavations at East Chisenbury, recording and analysing material exposed by badgers burrowing into the Late Bronze Age midden, in the midst of the MoD’s estate on Salisbury Plain. e season in 2012 at Barrow Clump aims to identify the extent of the Anglo-Saxon cemetery and to excavate all the burials. is positive and inspiring example of the value of archaeology has recently been recognised at the British Archaeological Awards with a special award for ‘Project of special merit’. You will find two advertising flyers in this mailing. Please consider making a gi of member - ship to a friend or relative for birthday, Christmas or graduation. Details of subscription rates appear in the notices towards the end of this Newsletter. FROM OUR NEW PRESIDENT David A. Hinton Professor David Hinton starts his three-year term as our President in October, when Professor David Breeze steps down. To follow David Breeze into the RAI presidency is daunting; his easy manner, command of business and ability to find the right word at the right time are qualities that all members who have attended lectures, seminars and visits, or been on Council and committees, will have admired. Our affairs have been in very safe hands during a difficult three years. In the last newsletter, David thanked the various people who have helped him in that period, and I am glad to have such a strong team to support me in turn. ere will be another major change in officers; Patrick Ottaway has reached the end of his term of editorship, and has just seen his final volume, 168, of the Archaeological Journal through the press; he has brought in a steady stream of articles that have kept it in the forefront of research publication. -

Methods in Digital Archaeology and Cultural Heritage Katy Meyers Emery

Methods in Digital Archaeology and Cultural Heritage Katy Meyers Emery Increasingly over the last decade, anthropologists have looked to digital tools as a way to improve their interpretations, engage with the public and other professionals, collaborate with other disciplines, develop new technology to improve the discipline and more. Due to the increasing importance of digital, it is important that current students become equipped with the skills and confidence necessary to creatively and thoughtfully apply digital tools to cultural heritage questions. With that in mind, this course is not a lecture- it is an open discussion and development course where students will learn digital tools by using and making them. This course will provide students with an introduction to digital tools in archaeology, from using social media to engage with communities to developing their own online projects to preserve, protect, share and engage with cultural heritage and archaeology. Course Goals: 1. Understand and articulate the benefits and challenges of digital methods within archaeology and cultural heritage management 2. Critically use digital methods to engage with the public and archaeological community online to promote cultural and archaeological heritage and preservation (ex. Blogging, Twitter, Digital Mapping, etc) 3. Leverage digital tools to create a digital project focused on archaeology or cultural heritage Texts: All reading material for this course will be provided online, although students may need to request or find their own reading material related to a historic site for their final project. **This syllabus was designed based on a course that I helped develop and teach over summer 2014, a Mobile Cultural Heritage Informatics class I assisted in during summer 2011, and my years as a Cultural Heritage Informatics Initiative fellow. -

Art: Authenticity, Restoration, Forgery

UCLA Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press Title Art: Authenticity, Restoration, Forgery Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5xf6b5zd ISBN 978-1-938770-08-1 Author Scott, David A. Publication Date 2016-12-01 Data Availability The data associated with this publication are within the manuscript. Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California READ ONLY/NO DOWNLOADS Art: Art: Authenticity, Restoration, ForgeryRestoration, Authenticity, Art: Forgery Authenticity, Restoration, Forgery David A. Scott his book presents a detailed account of authenticity in the visual arts from the Palaeolithic to the postmodern. The restoration of works Tof art can alter the perception of authenticity, and may result in the creation of fakes and forgeries. These interactions set the stage for the subject of this book, which initially examines the conservation perspective, then continues with a detailed discussion of what “authenticity” means, and the philosophical background. Included are several case studies that discuss conceptual, aesthetic, and material authenticity of ancient and modern art in the context of restoration and forgery. • Scott Above: An artwork created by the author as a conceptual appropriation of the original Egyptian faience objects. Do these copies possess the same intangible authenticity as the originals? Photograph by David A. Scott On front cover: Cast of author’s hand with Roman mask. Photograph by David A. Scott MLKRJBKQ> AO@E>BLILDF@> 35 MLKRJBKQ> AO@E>BLILDF@> 35 CLQPBK IKPQFQRQB LC AO@E>BLILDV POBPP CLQPBK IKPQFQRQB LC AO@E>BLILDV POBPP CIoA Press READ ONLY/NO DOWNLOADS Art: Authenticity, Restoration, Forgery READ ONLY/NO DOWNLOADS READ ONLY/NO DOWNLOADS Art: Authenticity, Restoration, Forgery David A.