How to Encourage Food Production in the City Published: October 2015 Version 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UWE Student Projects in St Pauls and Ashley Area 2020

UWE student projects in St Pauls and Ashley area 2020 Community led There are ongoing discussions for a proposal to form a community led Community parks: St Pauls, Interest Company (CIC) to take over and develop the parks/public green spaces in BSWN is a BME led infrastructure organisation that has Montpelier and St Pauls, Montpelier and St Werburghs from Bristol City Council. The outline brief worked extensively with BME communities and BME led St Werburghs is to investigate the green spaces and the local communities around these and put delivery organisations across the South West. BSWN forward proposals for community led inclusive parks that would support their engages with BAME people across Bristol’s communities viability going forwards with the aim of working with and for those marginalised in society due to their race or ethnicity; a discrimination that is often exacerbated by their socio-economic background and other factors of inequality such as gender, sexuality, faith, and disability. https://www.bristolpost.co.uk/news/property/five-most-family-friendly-places-1256021 Lead client Black South west Network (BSWB https://www.blacksouthwestnetwork.org/ Main contact Sibusiso Tshabalala Research Fellow BSWN Cognitive Paths [email protected] St Pauls Working with the local community, students are tasked with developing a brief and Museum: proposals for an aspirational, creative museum. A provisional site has been Black South West Network (BSWN)/Cognitive Paths Decolonising the selected but students need to think about key principles of the museum that might About Black South West Network (BSWN) museum work in another setting within St Pauls. -

Green Space in Horfield and Lockleaze

Horfield Lockleaze_new_Covers 16/06/2010 13:58 Page 1 Horfield and Lockleaze Draft Area Green Space Plan Ideas and Options Paper Horfield and Lockleaze Area Green Space Plan A spatial and investment plan for the next 20 years Horfield Lockleaze_new_Covers 09/06/2010 11:29 Page 2 Horfield and Lockleaze Draft Area Green Space Plan If you would like this Vision for Green Space in informationBristol in a different format, for example, Braille, audio CD, large print, electronic disc, BSL Henbury & Southmead DVD or community Avonmouth & Kingsweston languages, please contact Horfield & Lockleaze us on 0117 922 3719 Henleaze, Westbury-on-Trym & Stoke Bishop Redland, Frome Vale, Cotham & Hillfields & Eastville Bishopston Ashley, Easton & Lawrence Hill St George East & West Cabot, Clifton & Clifton East Bedminster & Brislington Southville East & West Knowle, Filwood & Windmill Hill Hartcliffe, Hengrove & Stockwood Bishopsworth & Whitchurch Park N © Crown Copyright. All rights reserved. Bristol City Council. Licence No. 100023406 2008. 0 1km • raising quality • setting standards • providing variety • encouraging use • Horfield Lockleaze_new_text 09/06/2010 11:42 Page 1 Ideas and Options Paper Horfield and Lockleaze Area Green Space Plan Contents Vision for Green Space in Bristol Section Page Park Page Gainsborough Square Park 8 1. Introduction 2 A city with good quality, Monks Park 9 2. Background 3 Horfield Common, including the Ardagh 10-11 attractive, enjoyable and Blake Road Open Space and 12 Rowlandson Gardens Open Space accessible green spaces which 3. Investment ideas and options to 7 Bonnington Walk Playing Fields 13 improve each open space within the area meet the diverse needs of all Dorian Road Playing Fields 14 4. -

Green Space in Ashley, Easton and Lawrence Hill

Ashley Easton Lawrence Hill AGSP_new_Covers 09/06/2010 11:24 Page 1 Ideas and Options Paper Ashley, Easton and Lawrence Hill Area Green Space Plan Ideas and Options Paper Ashley, Easton and Lawrence Hill Area Green Space Plan A spatial and investment plan for the next 20 years • raising quality • setting standards • providing variety • encouraging use • 1 Ashley Easton Lawrence Hill AGSP_new_Covers 09/06/2010 11:24 Page 2 Ideas and Options Paper Ashley, Easton and Lawrence Hill Area Green Space Plan If you would like this Vision for Green Space in informationBristol in a different format, for example, Braille, audio CD, large print, electronic disc, BSL Henbury & Southmead DVD or community Avonmouth & Kingsweston languages, please contact Horfield & Lockleaze us on 0117 922 3719 Henleaze, Westbury-on-Trym & Stoke Bishop Redland, Frome Vale, Cotham & Hillfields & Eastville Bishopston Ashley, Easton & Lawrence Hill St George East & West Cabot, Clifton & Clifton East Bedminster & Brislington Southville East & West Knowle, Filwood & Windmill Hill Hartcliffe, Hengrove & Stockwood Bishopsworth & Whitchurch Park N © Crown Copyright. All rights reserved. Bristol City Council. Licence No. 100023406 2008. 0 1km • raising quality • setting standards • providing variety • encouraging use • Ashley Easton Lawrence Hill AGSP_new_text 09/06/2010 11:18 Page 1 Ideas and Options Paper Ashley, Easton and Lawrence Hill Area Green Space Plan Contents Vision for Green Space in Bristol Section Page Park Page A city with good quality, 1. Introduction 2 Riverside Park and Peel Street Green Space 9 Rawnsley Park 10-12 attractive, enjoyable and 2. Background 3 Mina Road Park 13 accessible green spaces which Hassell Drive Open Space 14-15 meet the diverse needs of all 3. -

Lockleaze Neighbourhood Trust a Community Hub for Lockleaze

Lockleaze Neighbourhood Trust A community hub for Lockleaze April 2016 – March 2019 Final Strategic and Operational Plan 0 Contents 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................ 2 2. BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................................. 5 3. OUR VISION, MISSION, SERVICES AND VALUES ........................................................................................ 14 4. STRATEGIC PRIORITIES 2016 -2019 ........................................................................................................... 15 5. OPERATIONAL PLAN 2016-2019 ............................................................................................................... 16 APPENDIX 1 LOCKLEAZE RESIDENTS VIEWS ...................................................................................................... 22 APPENDIX 2 LOCKLEAZE DATA .......................................................................................................................... 24 APPENDIX 3 LIST OF CURRENT AND POTENTIAL NEW ACTIVITIES AT THE HUB AND CAMERON CENTRE ....... 26 APPENDIX 4 PARTNERSHIP DIAGRAM .............................................................................................................. 28 APPENDIX 5 PROPOSED ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURE AND STAFF ROLES .................................................... 29 APPENDIX 6 INCOME AND EXPENDITURE 2015 -

Great News for the CATT

GreatGreat newsnews forfor thethe CATTCATT BusBus Left -- LisaLisa GilbertGilbert fromfrom the the Mede Mede Sprint, Sprint, Dave ParryParry fromfrom thethe CATTCATT community community bus bus and NigelNigel BarrettBarrett fromfrom LawrenceLawrence Weston Weston Community TransportTransport The bid isis aa collaborationcollaboration between between CATT CATT community community bus, bus, the SprintSprint CommunityCommunity Transport Transport in in Knowle Knowle and and Lawrence Lawrence Weston CommunityCommunity Transport. Transport. The new fundingfunding starts starts on on 1st 1st July July 2017 2017 and and services services will will continue as usual. continue as usual. HWCP encouraged the CATT bus members to have their HWCP encouraged the CATT bus members to have their say on the council’s proposals, which included removing say on the council’s proposals, which included removing the use of bus passes on community transport. the use of bus passes on community transport. After consultation, the council decided to allow people to After consultation, the council decided to allow people to continue to use their bus passes on community transport. CATTcontinue bus to useusers their love bus their passes bus on community transport. TheCATT CATT bus bus users has nearlylove their 600 active bus members using the bus. LastThe CATTyear the bus CATT has nearly bus surveyed 600 active its membersusers and usingnearly the 60% bus. responded,Last year the CATTwhich bus is surveyeda very highits users response and nearly rate. 60% Theresponded, -

Breastfeeding Friendly Places Public Transport Citywide

The Bristol Breastfeeding Welcome Scheme: Breastfeeding Friendly Places Since June 2008 over 300 venues; cafes, restaurants, visitor attractions and community venues have joined the Bristol Breastfeeding Welcome scheme to support mothers to breastfeed when they are out and about with their babies. Public Transport First Bus Bristol was welcomed to the scheme in June 2010 and became the first bus company in the country to become breastfeeding friendly. Bristol Community Ferry Boats were welcomed to the scheme in February 2018. 44 The Grove, Bristol, BS1 4RB. Citywide Breastfeeding mothers are welcome at: • Health premises that include; hospitals, health centres, GP surgeries, community clinics and child health clinics. • Bristol City Council premises that include; children’s centres, libraries, museums, leisure centres, swimming pools and various other council buildings and facilities. Page | 1 Public Health Bristol 5 March 2019 Contents NORTH BRISTOL ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Avonmouth ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Horfield ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Bishopston .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Southmead -

Bristol Radical History Group

Bristol Radical History Group www.brh.org.uk ~ [email protected] Remembering The Real WW1 [email protected] - www.network23.org/realww1/ Bristol’s Conscientious Objectors Data Vrs. 1.1 - 27/04/2015 Bristol Radical History Group Bristol’s Conscientious Objectors Data: Ver. 1.0 About This Data Below are the names of 47 men from Bristol who were imprisoned from 1916 onwards as conscientious objectors. You may recognise a family member among them. If you do we would like to hear from you – we want to find out the background of these men and learn about their experiences during and after the war. The list of names is unlikely to be comprehensive. If you know of other men who were imprisoned for opposing the war please let us know. The names appear in two separate alphabetically ordered sections. Searching this file With this file open in your browser or Adobe Acrobat Reader press the ‘Ctrl’ key and the ‘F’ key (‘Cmd’ and ‘F’ on a Mac) simultaneously. This will open a search box, the location of which will depend on the browser you are using but it is normally top left or bottom right. www.brh.org.uk Page 2 [email protected] Bristol Radical History Group Bristol’s Conscientious Objectors Data: Ver. 1.0 Section 1 - Toleration or Persecution The first section lists 23 names from a document in the Central Library (entitled Toleration or Persecution). These men were imprisoned by August 1916. We have some address details for them. Where possible using the 1911 Census data we have been able to link them to specific house numbers and even found occupations and ages. -

The Equity Report October 2020

Equity Project 2019-20 Removing Barriers to Access at a City Farm in Bristol Exploring the barriers to access to urban farms for diverse communities, and presenting possible solutions Manu Maunganidze, Rhian Grant and Esme Worrell October 2020 Funded by Space to Connect - a partnership between The Co-op Foundation and the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. CONTENTS Foreword ............................................................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction and context ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Some notes on language ................................................................................................................................ 4 Space to Connect funding .............................................................................................................................. 4 Background of SWCF and Urban farming in general ..................................................................................... 4 What is St Werburghs City Farm? .................................................................................................................. 5 What is SWCF doing well? ............................................................................................................................. 5 Need for research ......................................................................................................................................... -

Lord Mayor's Diary W/C 20 July 2015

Bristol City Council Lord Mayor’s diary for weeks beginning December 4th and December 11th 2017 Please note that the Lord Mayor’s diary is subject to change at short notice. Monday December 4th • Full Council Pre Agenda Meeting –City Hall • LMCA Fundraising Sleigh Ride Tuesday December 5th • Brunelcare Carol Service – Christ the Servant Church Stockwood • St Peter’s Hospice - Light up a Life Service – Bristol Cathedral • Avon Youth – Lawrence Weston • Fishponds Brownies and Guides Wednesday December 6th • ‘Christmas At Home’ – Mansion House • Henleaze Christmas festival – Henleaze Road • Julian Trust Carol Service – 16 Little Bishop Street Thursday December 7th • Citizenship Ceremony – Old Council House • Romanian Reception and Art Exhibition – 1 Redland Road • University of Bristol Alumni Awards Friday December 8th • Bristol Plays Music Carol Service – Bristol Cathedral • The wizard of Oz – Redmaids High School Saturday December 9th • Muddy madness Race - Mojo Active Centre Almondsbury • Life Univercecity Awards – Old Fishponds Library Sunday December 10th • Dr Whites Charity Christmas Event • Freemasons Carols and Dinner – Lord Mayors Chapel / Freemason Hall • BRACE Carol Service – St John the Baptist Church • Guild of Guardians Carol Service and Supper – Lord Mayor’s Chapel • RYMA Awards – Passenger Shed Monday December 11th • Bristol Underprivileged Children’s Charity – Marriot Royal Hotel • Lord Mayors Children’s Appeal Carol Concert Tuesday December 12th • Full Council Pre Meet – City Hall • Alderman’s Christmas Lunch - Royal Marriot -

Bristol Archaeological Research Group 4

ISSN 0144 6576 □ ISSUE No. 2 1981 BRISTOLARCHAEOLOGICAL RESEARCH GROUP 4 ...... GI oucestershire SITE LOCATION PLAN \ ·"' ......·-, . 0 mil.. 5 I I,, ,1 ' '· ,, I I 0 kilamelres 8 I. \. .-. ,,,, ' I 'I •. I .... Avon ·-----\ ' -Jf WESTBURY - _ \ .-. I' MARSHFIELD ' ,I , * I , -Jf REDCLIFFE WRAXALL ;* I ; * I BEDMINSTER 'I I... - - - _, 'I I ·' *KELSTON ! ' I • ....\ ,/~-;- ' ,. - . ' Wilts. I. - . ' _.,,. .... -·•• ,., ....... -· - ·' .,,... I·"' \ ,·-·- ,,,, I ' Somerset I ,, -· ,I ·- · ......--· BARGCOMMITTEE 1981-82 Chairman D Dawson Vice-chairman ••...........••... R Knight Secretary •••......••.. T Coulson Membership Secretary •.... Mrs J Harrison Treasurer •••.........• J Russell Special Publications Editor .. L Grinsell Review Editor .••....••••. R Iles Secretary for Associates •.••. S Reynolds Fieldwork Advisor ••.. M Ponsford Parish Survey Organiser .. Mrs M Campbell Publicity Officer .• Mrs P Belsey Miss E Sabin, M Dunn, R Williams, J Seysell, A Parker, M Aston, Mrs M Ashley BARGMEMBERSHIP Ordinary members ...•.•.••.•• £4.00 Joint (husband and wife) ••.• £6.00 Senior Citizen or student ••• £2,80 Associate (under 18) ••••.••• £1.00 The official address of Bristol Archaeological Research Group is: BARG, Bristol City Museum, Queens Road, Bristol BS8 1RL. Further copies of this Review can be obtained from the Secretary at the above address. Editorial communications should be addresed to: R Iles, 46 Shadwell Road, Bristol BS? SEP. BARGReview 2 typed by June Iles. BARGis grateful to Bristol Threatened History Society for financial -

Step 1: What Is the Proposal? Please Explain Your Proposal in Plain English, Avoiding Acronyms and Jargon

Bristol City Council Equality Impact Assessment Form – St Werburgh’s Primary School Input (Please refer to the Equality Impact Assessment guidance when completing this form) Name of proposal Draft Model Risk Assessment for Schools Re- Opening after Covid-19 Closure Directorate and Service Area People , Education Services Name of Lead Officer Christina Czarkowski Crouch Step 1: What is the proposal? Please explain your proposal in Plain English, avoiding acronyms and jargon. This section should explain how the proposal will impact service users, staff and/or the wider community. 1.1 What is the proposal? The model risk assessment for School Re-Opening, has been prepared to assist Schools negotiate the various Public Health England guidance in relation to the risks associated with the COVID 19 virus. The assessment has been prepared to help Schools instigate suitable control measures to help protect the School’s Staff / Pupils and Visitors. The risk assessment has been fully completed for the planned wider opening of St Werburgh’s Primary School to children in Reception, Year 1 and Year 6. The proposal is to open for small groups of pupils in Reception, Year 1 and Year 6 initially on a part time basis form Monday 8th June if the government and Bristol City Council advise that it is safe for us to do so. This will ensure that children can be in a familiar setting with familiar staff and come back into school in a phased way. Each group of children will operate as a ‘bubble’ which will not come into contact with or interact with other ‘bubbles’ of children. -

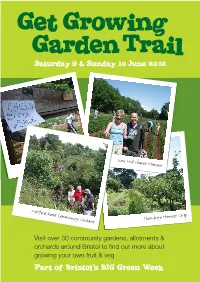

Get Growing Front+Back Final.Indd

Get Growing Garden Trail Saturday 9 & Sunday 10 June 2012 Bramble Farm Sims Hill Shared Harvest Metford Road Community Orchard Thornbury Harvest Co-op Visit over 30 community gardens, allotments & orchards around Bristol to fi nd out more about growing your own fruit & veg Part of Bristol's BIG Green Week 6 Community Farm 10 GREENS Community Market Garden Denny Lane, Chew Magna BS40 8SZ (Hartcliffe HHEAG) 11.30am–2.30pm Saturday Molesworth Allotments, Molesworth Drive Over 30 sites are open at various times The Community Farm is a social enterprise (between house nos 79 and 81), Get Growing Withywood BS13 9BJ over the weekend, showcasing a diverse established in April 2011. Owned by its 500 members, it holds education & volunteering days, runs training 10am–3pm Saturday range of growing projects. Each group and grows organic veg on 22 acres. Running a box GREENS grow fresh fruit and vegetables with the Garden Trail has a different way of organising the scheme with nearly 400 customers, the farm aims to help of volunteers at a community allotment site. reconnect people with where their food comes from The produce is used in nutrition and cooking courses, Saturday 9 & Sunday 10 June 2012 work, cultivating the land, and sharing through producing tasty organic veg. ACTIVITIES: See and is sold to course participants and other local the harvest – come and fi nd out what one of our volunteer days in action and meet some of people at low cost through our Food For All food the people involved! www.thecommunityfarm.co.uk co-op.