Crowdfunding in Museums Melanie R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of Oatmeal, Bears, and Npes: Ensuring Fair, Effective, and Affordable Copyright Enforcement Through Copyright Insurance Evan Mcalpine

Intellectual Property Brief Volume 4 | Issue 3 Article 2 7-10-2013 Of Oatmeal, Bears, and NPEs: Ensuring Fair, Effective, and Affordable Copyright Enforcement Through Copyright Insurance Evan McAlpine Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/ipbrief Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation McAlpine, Evan. "Of Oatmeal, Bears, and NPEs: Ensuring Fair, Effective, and Affordable Copyright Enforcement Through Copyright Insurance." Intellectual Property Brief 4, no. 3 (2013): 19-35. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Intellectual Property Brief by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Of Oatmeal, Bears, and NPEs: Ensuring Fair, Effective, and Affordable Copyright Enforcement Through Copyright Insurance This article is available in Intellectual Property Brief: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/ipbrief/vol4/iss3/2 Of Oatmeal, Bears, and NPEs: Ensuring Fair, Effective, and Affordable Copyright Enforcement Through Copyright Insurance by Evan McAlpine1 1ABSTRACT link-backs or attribution. Accordingly, he requested the site’s administrator remove the infringing copies via a Increasing copyright infringement and DMCA takedown notice.6 high litigation costs have left many independent After fruitlessly sending -

Dowthwaite, Liz (2018) Crowdfunding Webcomics

CROWDFUNDING WEBCOMICS: THE ROLE OF INCENTIVES AND RECIPROCITY IN MONETISING FREE CONTENT Liz Dowthwaite Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2017 Liz Dowthwaite Crowdfunding Webcomics: The Role of Incentives and Reciprocity in Monetising Free Content Thesis submitted to the School of Engineering, University of Nottingham, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. © September 2017 Supervisors: Robert J Houghton Alexa Spence Richard Mortier i To my parents, and James. ii Doug Savage, 2007 http://www.savagechickens.com/2007/05/morgan-freeman.html “They’re not paying for the content. They’re paying for the people.” Jack Conte, founder of Patreon “We ascribe to the idealistic notion that audiences don’t pay for things because they’re forced to, but because they care about the stuff that they love and want it to continue to grow.” Hank Green, founder of Subbable iii CROWDFUNDING WEBCOMICS – LIZ DOWTHWAITE – AUGUST 2017 ABSTRACT The recent phenomenon of internet-based crowdfunding has enabled the creators of new products and media to share and finance their work via networks of fans and similarly-minded people instead of having to rely on established corporate intermediaries and traditional business models. This thesis examines how the creators of free content, specifically webcomics, are able to monetise their work and find financial success through crowdfunding and what factors, social and psychological, support this process. Consistent with crowdfunding being both a large-scale social process yet based on the interactions of individuals (albeit en mass), this topic was explored at both micro- and macro-level combining methods from individual interviews through to mass scraping of data and large-scale questionnaires. -

A New Storytelling Era: Digital Work and Professional Identity in the North American Comic Book Industry

A New Storytelling Era: Digital Work and Professional Identity in the North American Comic Book Industry By Troy Mayes Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Discipline of Media, The University of Adelaide January 2016 Table of Contents Abstract .............................................................................................. vii Statement ............................................................................................ ix Acknowledgements ............................................................................. x List of Figures ..................................................................................... xi Chapter One: Introduction .................................................................. 1 1.1 Introduction ................................................................................ 1 1.2 Background and Context .......................................................... 2 1.3 Theoretical and Analytic Framework ..................................... 13 1.4 Research Questions and Focus ............................................. 15 1.5 Overview of the Methodology ................................................. 17 1.6 Significance .............................................................................. 18 1.7 Conclusion and Thesis Outline .............................................. 20 Chapter 2 Theoretical Framework and Methodology ..................... 21 2.1 Introduction .............................................................................. 21 -

I Driverless Vehicles' Potential Influence on Cyclist and Pedestrian

Driverless Vehicles’ Potential Influence on Cyclist and Pedestrian Facility Preferences THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of City and Regional Planning in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Michael Julian Armstrong Blau, BA Graduate Program in City and Regional Planning The Ohio State University 2015 Master's Examination Committee: Gulsah Akar, advisor Jack Nasar Jason Sudy i Copyright by Michael Julian Armstrong Blau 2015 ii Abstract Research in the field of autonomous vehicle technology focuses on the enhanced safety and convenience it will likely convey to vehicle occupants. This thesis seeks to establish a new and equally important line of inquiry that addresses the same implications for cyclists and pedestrians. It is well-established that motorized traffic volume and speed have a strong influence on non-motorized agents’ behavior and facility preference but whether this will continue to be the case in a driverless environment remains unknown. A stated-preference survey was crafted asking respondents to select their preferred facility in various scenarios with and without the presence of driverless vehicles and on street types of varying motorized traffic volumes and speeds. An ordered logit model was estimated to illustrate that street type had a very strong influence on cyclists’ preferences for more separated facilities as traffic volume and speed increased. The presence of driverless vehicles significantly amplified this trend. Preferences for bike intersection features, pedestrian facilities, and pedestrian crossing behavior are also examined. Infrastructure and policy recommendations are presented as well as suggestions for future research in this nascent field of study. -

August 2014 NASFA Shuttle

Te Shutle August 2014 The Next NASFA Meeting is Saturday 16 August 2014 at the Regular Location d Oyez, Oyez d ! RIP Louise Kennedy The next NASFA Meeting will be 6P Saturday 16 August by Mike Kennedy 2014, at the regular meeting location—the Madison campus of ! Willowbrook Baptist Church (old Wilson Lumber Company I thought a considerable time about whether to run an building) at 7105 Highway 72W (aka University Drive). obituary for my mother in this issue. Most local folks—and Please see the map on page 2 if you need help finding it. many who aren’t—were informed by various means within AUGUST PROGRAM the first 24 hours. Still, there are some Shuttle readers who Unfortunately, the previously-planned program by Les John- may want to know and who haven’t heard in other ways. So, son fell prey to a conflict. Les has asked for a rain check and despite this being the hardest thing I’ve ever written, here will talk about Mars Exploration and Rescue Mode (his latest goes. book) at a to-be-determined future date. The new program for Louise Maples Kennedy died on Monday 4 August 2014. August is TBD at press time. She is survived by me; my brother, Jim; Jim’s wife, Tracey; AUGUST ATMM and their two sons, Joshua and Aaron. Mom was one of nine The After-The-Meeting Meeting host is TBD at press time, children and was the last survivor of her siblings. She was but there’s a high probability that it will take place at the buried Thursday 7 August beside Dad, William David “Bill” church. -

Enlightened Entrepreneurship: the Success of Elon Musk

Enlightened entrepreneurship: the success of Elon Musk Department of Economics & Business Chair of Entrepreneurship, Technology and Innovation Supervisor: Professor Andrea Prencipe Candidate: Mathias Mair ID 180631 Academic year 2015/2016 1 Table of contents: Introduction 1- What is entrepreneurship? 1.1- History of entrepreneurship 1.2- Behavioural patterns in entrepreneurs 1.3- Communication fundamentals in entrepreneurs 1.4- Financing 2- History of Musk’s rise, his life and career 2.1- Early life 2.2- Career beginnings: Zip2 and PayPal 2.3- SpaceX: the multiplanetary dream 2.4- The transportation adventure: Tesla Motors 2.5- The transportation adventure: Hyperloop 2.6- Solar City and Open AI 3- List of Musk’s keys to success 3.1- Main points of his philosophy 3.2- Family, philanthropy and awards 4- Conclusion 5- Bibliography 2 Introduction The purpose of this thesis is to analyse in depth the strategies, methods and actions that allowed Elon Musk to place himself as a top tier entrepreneur. Starting from the true meaning of entrepreneurship, I moved into taking to account the points in common between Musk and what a nowadays entrepreneur needs to be capable of. I followed by underlining the focal achievements reached in his career and what he might have used to get to reach his goals, mostly his personality traits. At last I demonstrated how he affected the culture of this days and how he rewrote the definition of pathfinder in the entrepreneurial world. 1 What is entrepreneurship? Entrepreneurship is defined as the process of starting and running a business in a strategic way in order to make a profit from a product or service. -

The Uses and Gratifications Behind Farmers Using Twitter

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Theses from the College of Journalism and Journalism and Mass Communications, College Mass Communications of 5-2011 An iPhone in a Haystack: The Uses and Gratifications Behind Farmers Using Twitter Sarah Van Dalsem University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/journalismdiss Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Van Dalsem, Sarah, "An iPhone in a Haystack: The Uses and Gratifications Behind armersF Using Twitter" (2011). Theses from the College of Journalism and Mass Communications. 11. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/journalismdiss/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journalism and Mass Communications, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses from the College of Journalism and Mass Communications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. AN IPHONE IN A HAYSTACK: THE USES AND GRATIFICATIONS BEHIND FARMERS USING TWITTER by Sarah Van Dalsem A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Major: Journalism and Mass Communications Under the Supervision of Professor Sue Burzynski Bullard Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2011 AN IPHONE IN A HAYSTACK: THE USES AND GRATIFICATIONS BEHIND FARMERS USING TWITTER Sarah Van Dalsem, M.A. University of Nebraska, 2011 Adviser: Sue Burzynski Bullard The fast-growing social media site, Twitter, is growing in popularity among Americans from all walks of life, including farmers who are using it to share information with other farmers and consumers. -

(SBN 159477) Rtang

Case3:12-cv-03112-EMC Document22-1 Filed07/01/12 Page1 of 3 1 DURIE TANGRI LLP RAGESH K. TANGRI (SBN 159477) 2 [email protected] MARK A. LEMLEY (SBN 155830) 3 [email protected] EUGENE NOVIKOV (SBN 251316) 4 [email protected] 217 Leidesdorff Street 5 San Francisco, CA 94111 Telephone: 415-362-6666 6 Facsimile: 415-236-6300 7 Attorneys for Defendant INDIEGOGO, INC. 8 9 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 10 FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 11 SAN FRANCISCO DIVISION 12 CHARLES CARREON, Case No. 3:12-cv-03112-EMC 13 Plaintiff, DECLARATION OF RAGESH TANGRI 14 v. 15 MATTHEW INMAN; INDIEGOGO, INC.; NATIONAL WILDLIFE FEDERATION; 16 AMERICAN CANCER SOCIETY; AND DOES 17 1-100, 18 Defendants. 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 DECLARATION OF RAGESH K. TANGRI / CASE NO. 3:12-CV-03112-EMC Case3:12-cv-03112-EMC Document22-1 Filed07/01/12 Page2 of 3 1 I, Ragesh Tangri, declare as follows: 2 1. I am a member of the State Bar of California and counsel of record for Defendant 3 Indiegogo Inc. in the above-captioned litigation. 4 2. On June 28, 2012, at 4:55 p.m., Plaintiff Charles Carreon served an application for a 5 temporary restraining order and order to show cause why a preliminary injunction should not issue. A 6 true and correct copy of the email transmitting Carreon’s papers is attached to this declaration as Exhibit 7 A. 8 3. At 7:02 p.m. that evening, Carreon served a revised version of his supporting declaration 9 and exhibits. -

Gov.Uscourts.Cand.256114.25.0.Pdf Download

Case3:12-cv-03112-EMC Document25 Filed07/01/12 Page1 of 5 1 Kurt Opsahl (SBN 191303) [email protected] 2 Matthew Zimmerman (SBN 212423) 3 [email protected] Corynne McSherry (SBN 221504) 4 [email protected] ELECTRONIC FRONTIER FOUNDATION 5 454 Shotwell Street San Francisco, CA 94110 6 Telephone: (415) 436-9333 7 Facsimile: (415) 436-9993 8 Venkat Balasubramani (SBN 189192) [email protected] 9 Focal PLLC 800 Fifth Avenue, Suite 4100 10 Seattle, WA 98104 11 Telephone: (206) 529-4827 Facsimile: (206) 260-3966 12 Attorneys for Defendant Matthew Inman 13 14 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 15 FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 16 SAN FRANCISCO DIVISION 17 CHARLES CARREON, ) Case No.: 12-cv-3112-EMC ) 18 Plaintiff, ) ) 19 DECLARATION OF KURT OPSAHL IN v. ) ) OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFF’S 20 ) APPLICATION FOR A TEMPORARY MATTHEW INMAN, INDIEGOGO, INC., ) RESTRAINING ORDER 21 NATIONAL WILDLIFE FEDERATION, AND AMERICAN CANCER SOCIETY, ) ) Date: TBD 22 and Does 1 – 100, ) Defendants, Time: TBD ) Courtroom: 5 – 17th Floor 23 ) and ) Judge: Hon. Edward M. Chen 24 ) KAMALA HARRIS, Attorney General of the ) 25 State of California, ) ) 26 A Person To Be Joined If ) ) 27 Feasible Under Fed. R. Civ. P. 19 )) 28 No.: 12-cv-3112-EMC OPSAHL DECL. IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFF’S APPLICATION FOR A TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER Case3:12-cv-03112-EMC Document25 Filed07/01/12 Page2 of 5 1 I, Kurt Opsahl, of full age, certify, declare and state: 2 1. I am an attorney at law, duly licensed and admitted to practice in the State of 3 California. -

Copyrighted Material

BINDEX 09/12/2017 1:17:21 Page 284 Index A AIR MILES, 251–252 Accuracy, speed vs., 201–202 Al-Asady, Zaid, 193 Actions, by leaders, 19 Alexis, Michael, 199 Activism, on social media, Alexis, Michaela, 38, 150 256–258 Algar, Trevor, 237 AdBlocker, 164–165 ALS Association (ALSA), ADT Canada, 12–14 256–258 Advertising: “ALS Ice Bucket Challenge,” changes in creation of, 225 256–258 false, 110–111 Amazon, 275–277 on Google Home, 27 Amazon.com, 134 Super Bowl,COPYRIGHTED 140 Amazon MATERIAL Go, 276 Advertising campaigns, plagiarism American Airlines, 188–189 in, 112–115 American Cancer Society, 102 Advisors: Anderson, Ami, 96 and crowdfunding platforms, 135 Andrew, Jill, 98 seeking out, 63 Apple, 1, 2, 162–163 Agrawal, Miki, 62 ARF David Ogilvy Awards, 196 AirBnb, 206 Artwork, online theft of, 36–38 284 BINDEX 09/12/2017 1:17:21 Page 285 Index 285 Ashley Home Furniture Store, Beautification app, at Samsung, 73–74 78–79 Associated Press, 39 Beauty and the Beast (film), 26–27 Astley, Amy, 117 Be Bangles, 143–145 Atari, 93, 94 Belhouse, Nadine, 150 Atomic Spark Video, 159–160 Benefit corporations, 22 Attention: Bensi, 90 to broader market, 188–189 Benson, Michael, 170–173 to positive social media postings, Best Western, 206–208 254–255 Bezos, Jeff, 196, 275–277 Attleboro, Massachusetts, 96 Big Ass Fans, 75 Audience: Big Cheese Club promotion, 122 building, via social media, 101 Bissell, 232 for Super Bowl Bissell, Kathy, 232 advertisements, 140 BitTorrent, 212–213 Audits, company, 6–8 Blaskie, Erin, 24–25 Australia Post, 143–145 Bloomberg, 89, 275 Autism, Chuck E. -

Downloading Process: You’Re Gonna Sit Still, and I’M Gonna Shove Some Stuff in Your Brain, and You’Re Gonna Keep It There.”

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Seeking Higher Ground: Contemporary Back-to-the-Land Movements in Eastern Kentucky Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/29n6997m Author Strange, Jason George Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Seeking Higher Ground: Contemporary Back-to-the-Land Movements in Eastern Kentucky by Jason George Strange A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geography in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Michael Watts, Chair Professor Michael Johns Professor Michael Burawoy Fall 2013 Seeking Higher Ground: Contemporary Back-to-the-Land Movements in Eastern Kentucky © 2013 Jason George Strange Abstract Seeking Higher Ground: Contemporary Back-to-the-Land Movements in Eastern Kentucky By Jason George Strange Doctor of Philosophy in Geography University of California, Berkeley Professor Michael Watts, Chair When I was growing up in the beautiful Red Lick Valley in eastern Kentucky, I saw many families practicing intensive subsistence production. They grew large gardens, raised chickens for eggs and meat, built their own homes, and fixed their own cars and trucks. On the Yurok Reservation, I again saw a profound and ongoing engagement with hunting, gathering, and crafting activities – and then encountered contemporary subsistence yet again when I visited my wife’s childhood home in rural Ireland. When I began my graduate studies, however, I could find little reflection of these activities in either the scholarly record or popular media. When they were noticed at all, they were often targeted for stereotyped ridicule: contemporary homesteaders in the US were either remnant hippies from the ‘60s, or quaint mountain folks lost in time. -

The Engineer.Pdf

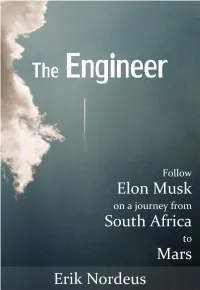

The Engineer Follow Elon Musk on a journey from South Africa to Mars Erik Nordeus This book is for sale at http://leanpub.com/theengineer This version was published on 2014-08-19 This is a Leanpub book. Leanpub empowers authors and publishers with the Lean Publishing process. Lean Publishing is the act of publishing an in-progress ebook using lightweight tools and many iterations to get reader feedback, pivot until you have the right book and build traction once you do. ©2013 - 2014 Erik Nordeus Contents Preface ........................ 1 Introduction ..................... 6 Sand Hill Road .................... 10 Lost Cities ...................... 16 Boredom Leads to Great Things .......... 35 What Do I Do Now? ................. 52 The Meaning of Life ................. 61 The Outsider ..................... 82 Joining the Mafia .................. 95 I Don’t Need These Russians ............ 113 Launching a Truck Into Space ........... 136 The Electric Stars .................. 147 CONTENTS You Can’t Sell a Car That Looks Like Crap .... 170 Tesla’s Macintosh .................. 187 Trouble in Paradise ................. 196 Iceberg, Right Ahead ................ 211 Another Iceberg, Right Ahead ........... 219 Revenge ........................ 237 Halfway to Anywhere ............... 254 The Leaning Factories ................ 270 A Burning Man ................... 290 Joining the Thrillionaires .............. 309 Idea Overload .................... 323 End of the Beginning ................ 335 Timeline ....................... 342 Elon Musk . 342 Tesla Motors . 343 SpaceX . 351 Sources ........................ 354 Preface The history of The Engineer - Follow Elon Musk on a journey from South Africa to Mars began in 2006 when I read a book about peak oil. The idea behind peak oil is that the world sooner or later will run out of oil because oil is a finite resource. Most books written on the subject are within the doomsday category.