Appraisal of Rail Projects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Class 465/466 Enhancement Pack Volume 1

Class 465/466 Enhancement Pack Volume 1 Contents How to Install ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Liveries ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 Keyboard Controls .................................................................................................................................. 8 Features ...................................................................................................................................................... 9 Variations ............................................................................................................................................... 9 Driver Only Operation (DOO) ....................................................................................................... 12 Wheelslip Protection (WSP) .......................................................................................................... 13 Speed Set ............................................................................................................................................. 14 Accelerometer, Decelerometer & Clock ................................................................................... 14 Player Changeable Destination Display .................................................................................... 15 Automatic Unit Numbering .......................................................................................................... -

Railway Development Society Limited Is a Not-For-Profit Company Limited by Guarantee Registered in England & Wales No.5011634

railse no. 128 June 2015 Railfuture in London and the South East quarterly branch newsletter The independent campaign for a better passenger and freight rail network Terminal decline of diesels Refreshing electrification London terminals – a group of 14 mainline stations The most recent Network Rail strategy on electrification spread around Zone 1, all but one of which are fully was the Network RUS published back in October 2009. equipped for electric traction, yet half of them are still Since September 2012 the Network RUS Working invaded by noisy, smelly and polluting diesel trains. Group: Electrification ‘refresh’ remit has been to review That’s not to mention the diesels’ higher operating and options for further electrification over the next 30 years, maintenance costs, and generally poorer performance and consider a priority for delivery. A consultation draft in terms of reliability and acceleration. Railfuture has is expected imminently, postponed from pre-purdah. long advocated the various benefits of electric traction. The drivers for further electrification are seen as: ~ reduced rolling stock leasing, maintenance and operating costs; ~ reduced infrastructure maintenance costs; ~ improved rolling stock reliability; ~ reduced journey times and potential reduction in rolling stock requirement; ~ shorter freight routeings and potential release of capacity through more consistent train performance; ~ ability to haul greater freight loads; ~ enhancing capacity on un-electrified routes through cascade of diesel rolling stock; ~ increased network availability through provision of diversionary routes; ~ lower emissions and reduced noise; ~ compliance with environmental policy legislation. The shape of things to come – IEP train for Paddington The ‘Smelly Seven’ stations are: Euston – Virgin’s Voyagers King’s Cross – Grand Central and Hull Trains London Bridge – Southern’s Turbostars, to Uckfield Marylebone – the only all-diesel London terminus Paddington – all, except Heathrow Express/Connect St. -

Competitive Tendering of Rail Services EUROPEAN CONFERENCE of MINISTERS of TRANSPORT (ECMT)

Competitive EUROPEAN CONFERENCE OF MINISTERS OF TRANSPORT Tendering of Rail Competitive tendering Services provides a way to introduce Competitive competition to railways whilst preserving an integrated network of services. It has been used for freight Tendering railways in some countries but is particularly attractive for passenger networks when subsidised services make competition of Rail between trains serving the same routes difficult or impossible to organise. Services Governments promote competition in railways to Competitive Tendering reduce costs, not least to the tax payer, and to improve levels of service to customers. Concessions are also designed to bring much needed private capital into the rail industry. The success of competitive tendering in achieving these outcomes depends critically on the way risks are assigned between the government and private train operators. It also depends on the transparency and durability of the regulatory framework established to protect both the public interest and the interests of concession holders, and on the incentives created by franchise agreements. This report examines experience to date from around the world in competitively tendering rail services. It seeks to draw lessons for effective design of concessions and regulation from both of the successful and less successful cases examined. The work RailServices is based on detailed examinations by leading experts of the experience of passenger rail concessions in the United Kingdom, Australia, Germany, Sweden and the Netherlands. It also -

Transforming the Countryside the Electrification of Rural Britain 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

TRANSFORMING THE COUNTRYSIDE THE ELECTRIFICATION OF RURAL BRITAIN 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Paul Brassley | 9781472441270 | | | | | Transforming the Countryside The Electrification of Rural Britain 1st edition PDF Book New other. By , two-thirds of rural dwellings had been connected to a centrally generated supply, but the majority of farms in Britain were not linked to the mains until sometime between and Converted from 6. The Independent. The system was converted to third rail in see below. By using our services, you agree that we may use cookies. Retrieved 19 May Advertisement Hide. The Cumbernauld Line to Springburn and the remaining section of the Motherwell to Cumbernauld Line was electrified in mid See all articles in The revolution of electricity. Archived from the original on 27 August British Railways chose this as the national standard for future electrification projects outside of the third rail area in Dublin: Stationery office. In , the government's preferred option was to use diesel trains running on biodiesel , its White Paper Delivering a Sustainable Railway , [6] ruling out large-scale railway electrification for the following five years. In the s, the lines to Chingford, Enfield Town and Cheshunt were electrified at 6. Deposit Details. About this product Product Information It is now almost impossible to conceive of life in western Europe, either in the towns or the countryside, without a reliable mains electricity supply. Item Type: Book. Rail transport in Scotland is a devolved matter for the Scottish Government but they too have pursued electrification with multiple schemes in the Central Belt. During the early s, the whole of this line was converted to 6. -

Railway Development Society Limited Is a Not-For-Profit Company Limited by Guarantee Registered in England & Wales No.5011634

railse no. 132 June 2016 Railfuture in London and the South East quarterly branch newsletter The independent campaign for a bigger better passenger and freight rail network Railfuture campaign wins reopened National Infrastructure Commission east London station at Lea Bridge wants Crossrail 2 hybrid bill in 2019 Between Stratford and Tottenham Hale, opened on Lord Adonis and his team of seven Commissioners 15 September 1840, closed 8 July 1985 with the end of may only have been appointed since last October, and Stratford-Tottenham Hale shuttle services, reopened the CEO since December, but their output and current 31 years later on 15 May 2016 (officially on 16 May). casework is already substantial. For London and the South East there has been last November’s Call for Evidence on London’s Transport Infrastructure, to which Railfuture responded in January, and which in March resulted in two reports: ‘Transport for a World City’ and, from an independent panel of experts, the supporting ‘Review of the case for large scale transport investment in London’ both of which include a specific focus on Crossrail 2. The NIC calls for a hybrid bill deposit in autumn 2019 for line opening in 2033, to coincide with HS2 opening to Leeds and Manchester and the need for the double- ended Euston St. Pancras station to add distribution capacity. It also advocates deferral of the £4billion New Southgate branch, noting that it would enable the proposed eastern extension to be considered when the Lea Bridge station – looking south, towards Stratford second phase of the scheme is planned. It “would be more expensive, but could bring greater overall This is the culmination of a campaign which local benefits, particularly in relation to its impacts in Railfuture members, individual and affiliated, can justly unlocking housing and economic growth in the east of claim as their own. -

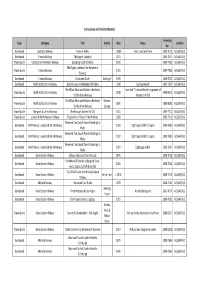

Publicity Material List

Early Guides and Publicity Material Inventory Type Company Title Author Date Notes Location No. Guidebook Cambrian Railway Tours in Wales c 1900 Front cover not there 2000-7019 ALS5/49/A/1 Guidebook Furness Railway The English Lakeland 1911 2000-7027 ALS5/49/A/1 Travel Guide Cambrian & Mid-Wales Railway Gossiping Guide to Wales 1870 1999-7701 ALS5/49/A/1 The English Lakeland: the Paradise of Travel Guide Furness Railway 1916 1999-7700 ALS5/49/A/1 Tourists Guidebook Furness Railway Illustrated Guide Golding, F 1905 2000-7032 ALS5/49/A/1 Guidebook North Staffordshire Railway Waterhouses and the Manifold Valley 1906 Card bookmark 2001-7197 ALS5/49/A/1 The Official Illustrated Guide to the North Inscribed "To Aman Mosley"; signature of Travel Guide North Staffordshire Railway 1908 1999-8072 ALS5/29/A/1 Staffordshire Railway chairman of NSR The Official Illustrated Guide to the North Moores, Travel Guide North Staffordshire Railway 1891 1999-8083 ALS5/49/A/1 Staffordshire Railway George Travel Guide Maryport & Carlisle Railway The Borough Guides: No 522 1911 1999-7712 ALS5/29/A/1 Travel Guide London & North Western Railway Programme of Tours in North Wales 1883 1999-7711 ALS5/29/A/1 Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, Liverpool & Wirral Railway 1902 Eight page leaflet/ 3 copies 2000-7680 ALS5/49/A/1 Wales Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, Liverpool & Wirral Railway 1902 Eight page leaflet/ 3 copies 2000-7681 ALS5/49/A/1 Wales Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, -

Feature London's Railways—Their Contribution to Solving the Problem

Feature Evolution of Urban Railways London’s Railways—Their Contribution to Solving the Problem of Growth and Expansion John Armstrong and Terry Gourvish Capital cities are usually the most south and east, catered for short-distance There was some truth to this claim, but populous urban centres in a country. They traffic but they were soon followed by the what of the displaced inhabitants? Their are also likely to be the largest in termini for long-distance lines, such as numbers were considerable. Dyos geographical area and hence transport Euston in 1837 for the north and west, and estimated that 76,000 people were problems are liable to occur first and to a Paddington a year later for the west via displaced between 1853 and 1901 by larger extent in capitals than in any other Reading, Swindon and Bristol. These latter railway schemes in London6 . Because towns. London in the nineteenth century railways had little impact on mass intra- these people were mostly poor and fitted this model. It was by far the most urban travel. Their fares were too high worked long hours for low wages, they populous city in Great Britain and its and they did not really cater for short- could afford neither the time nor the population grew by about 20% every distance commuters, being more money to move very far from their place decade, from about 1 million in 1801 to interested in long-distance, inter-city of work. Consequently, when their 4 million in 1871 and over 7 million just movement. existing dwellings were demolished, they before WWI1 . -

Loco DLC Manual

Class 159 Network SouthEast © Copyright Dovetail Games 2015, all rights reserved Release Version 1.0 Train Simulator 2015 – Class 159 Network SouthEast 1 BACKGROUND .................................................................................................. 3 1.1 Class 159 ..................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Design & Specification .................................................................................. 3 2 ROLLING STOCK ............................................................................................... 4 2.1 Class 159 Network SouthEast ....................................................................... 4 2.2 Class 43 “High Speed Train” InterCity Swallow ............................................... 4 3 DRIVING THE CLASS 159 .................................................................................. 5 3.1 Cab Controls ................................................................................................ 5 3.2 Locomotive Keyboard Controls ...................................................................... 5 3.3 General Keyboard Controls ........................................................................... 5 4 DRIVING THE CLASS 43 .................................................................................... 7 4.1 Cab Controls ................................................................................................ 7 4.2 Locomotive Keyboard Controls ..................................................................... -

MISSING LINKLINK the Newsletter of the Wealden Line Campaign No

MISSINGMISSING LINKLINK The Newsletter of the Wealden Line Campaign No. 54 Winter 2018 SOUTH EAST MPs CHAMPION BML2 GOVERNMENT NOW URGING A SPEEDY DELIVERY OF ITS BUSINESS CASE “I would be delighted to see BML2 go ahead, as the reopening of Tunbridge Wells West would be a real boon to the town – bringing greater choice and more services both to London and other parts of Kent and Sussex. I’m therefore thrilled to see that work continues at pace. “Reopening lines closed in the 1960s and 70s is also an important part of the Government’s new rail strategy,BBC NEWSand the Secretary of State for Transport has warmly welcomed the BML2 consortium’s endeavours.” - The Rt Hon Greg Clark MP and Secretary of State Tunbridge Wells MP Greg Clark for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Lewes MP Maria Caulfield discussing BML2 with the Transport Secretary Chris Grayling. Photo Sussex Express “As MP for Lewes, Newhaven, Seaford and Polegate, I am The great problem we face in the South East is a lack of passionate about BML2 because I am keenly aware of the capacity, which is why I agree with everyone who believes we difficulties faced by all my constituents who depend on rail need to restore our second main line between the Sussex Coast services. The Government is currently spending £300m on and London. Everybody knows this will help enormously upgrading the Brighton Line which in itself is very welcome whenever the Brighton line is out of action, whether it is investment. This will certainly go some way to ameliorate some engineering work or unforeseen calamities. -

SWT Supplement Cover MR Edition.Indd 1 03/08/2017 16:01 CREATING DESIRE

21 YEARS OF 19962017 A STAGECOACH GROUP PUBLICATION IN PARTNERSHIP WITH MODERN RAILWAYS MODERN RAILWAYS EDITION 001_SWT Supplement_cover_MR edition.indd 1 03/08/2017 16:01 CREATING DESIRE Understanding and respecting train architecture - its rhythms, resonances, form and function - is the first step to creating a stunning livery. For over 30 years Our designs accentuate the personality that lies within the architecture of Best Impressions has been ahead of any vehicle. Livery and form then have the curve when it comes to redefining how natural sympathy and, brought together public transport is presented, perceived and sold. through good design, communicate far more effectively. We have created commanding brands, produced Add in our unbridled passion, clear vision, award-winning advertising and marketing campaigns, effervescent enthusism and in-depth powerful corporate identities, stylish interiors and understanding of the South West Trains designed so many drop-dead-gorgeous liveries brand, and you can see how our use of full-on, bold, primary colours balanced . as progressive operators keep discovering. with outrageous, sexy curves has given these commuter trains - and other rolling stock types in the South West Trains’ fleet - a vibrant, contemporary, stylish tilt. 15 STARFIELD ROAD LONDON W12 9SN 020 8740 6443 [email protected] BRANDING LIVERY INTERIOR MARKETING DIGITAL BestImpressions_FP.inddBI-SWT.ad.indd 1 1 03/08/2017 09:3305:52 21 YEARS OF 5 STEAM, SOUTHERN ELECTRIC AND NETWORK SOUTHEAST 21 YEARS OF The history of the South Western prior to SWT 19962017 7 21YEAR TIME TEAM A STAGECOACH GROUP PUBLICATION IN PARTNERSHIP WITH MODERN RAILWAYS The story of Stagecoach’s tenure at South West Trains 10 MORE AND LONGER TRAINS Focus on the South Western capacity expansion programme 13 WHAT HAS CHANGED IN 21 YEARS? Improvements to stations and trains have been a key feature of Stagecoach’s operation 16 THE VIEW FROM THE TOP Current and former SWT managing directors reflect on the past 21 years Cover images: SWT photo library and PaulBigland. -

Delivering a Sustainable Railway Cm 7176

Delivering a Sustainable Railway July 2007 Delivering a Sustainable Railway Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Transport, by Command of Her Majesty July 2007 Cm 7176 £25.00 The Department for Transport has actively considered the needs of the partially sighted in accessing this document. The text will be made available in full on the web site in accordance with the W3C’s Web Accessibility Initiative’s criteria. The text may be freely downloaded and translated by individuals or organisations for conversion into other accessible formats. If you have other needs in this regard, or you are a carer for someone who has, please contact the Department. With certain exceptions, such as safety, rail policy is a devolved matter in Scotland, so the geographical scope of the strategy is primarily limited to England and Wales, recognising the powers of the Welsh Assembly Government in relation to Welsh and cross-border services. Department for Transport Great Minster House 76 Marsham Street London SW1P 4DR Telephone 020 7944 8300 © Crown copyright 2007 Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with the Crown. This publication, excluding logos, may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium subject to it being reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title specified. To reproduce maps, contact Ordnance Survey via their web site www.ordnancesurvey.gov.uk/copyright or write to Customer Service Centre, Ordnance Survey, Romsey Road, Southampton SO16 4GU. For any other use of this material, apply for a Click-Use Licence at www.opsi.gov.uk/click-use/index.htm, or by writing to the Licensing Division, Office of Public Sector Information, St Clements House, 2-16 Colegate, Norwich NR3 1BQ, fax 01603 723000, e-mail [email protected] Printed in Great Britain on paper containing at least 75% recycled fibre. -

SWR Class 442 Converter Mod Case Study

AEGIS Case Study Project title Class 442 NEI Converter Modification Client name South Western Railways Date June 2020 SCOPE/OBJECTIVE British Rail Class 442 electric multiple unit trains were first introduced to the railway in 1988 by Network Southeast. Since then they have operated on the South Western Main Line from London Waterloo to Weymouth, coinciding with the electrification of the line from Bournemouth. Currently, eighteen are in service with South Western Railways (SWR), operating between London Waterloo and Portsmouth Harbour. Class 442 units fitted with Northern Engineering Figure 1 - Identifying measurement positions with SWR Industries (NEI) auxiliary converters had previously been causing Right Side Failure of a Signal cables from these sensors are routed back TI21/ ET200 track circuit (‘ND’) in the Wimbledon into the passenger compartment where they are area. AEGIS were contracted by South West digitalized by a Dewe-43A, providing live results Railway (SWR) to investigate this by measuring in Dewesoft (shown in Figure 2) and data for the conducted emissions of the converter. The post-test analysis. results of the investigation identified that auxiliary converter emissions, possibly increased by interaction with the traction power supply ripple, are likely to be a factor in this issue. NEI modified the converters which resolved the issues, with the modified units now being used in service. TECHNOLOGY USED (IF APPLICABLE) Measuring the conducted emissions entails: measuring the line voltage and AC line current. Alongside these, GPS data is recorded for speed, direction and location to inform the results. To record the line voltage and current, voltage Figure 2 - Live Dewesoft results probes and Rogowski coils are attached to cables on the underframe of the train.