Michelangelo As Leonardo Knew He Loved the Florentine Poet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Dama Del Armiño Janusz Wałek Conservador Del Museo Nacional De Cracovia

La Dama del Armiño Janusz Wałek Conservador del Museo Nacional de Cracovia Leonardo da Vinci pintó La Dama del Armiño, también conocida como Retrato alegórico de Cecilia Gallerani, hacia 1490, en el período en que trabajó al servicio del duque milanés Ludovico el Moro. El cuadro fue adquirido –ignoramos a quién– por el príncipe Adam Jerzy Czartoryski hacia 1800 y seguramente en Italia. Pasó enseguida a manos de su madre, la princesa Izabela Czartoryska, de soltera Fleming, quien en 1801 creó en Puławy el primer museo polaco abierto al público. Sin identificar a la modelo, Czartoryska lo denominó La Belle Ferronnière, probablemente por su similitud con el grabado de otro retrato de Leonardo que se halla hoy en el Museo del Louvre. Parece que fue por entonces cuando se le añadió en la esquina superior izquierda la inscripción «LA BELE FERONIERE / LEONARD D’AWINCI». La utilización de la W (inexistente en italiano) en el apellido del pintor es quizás deliberada, para adaptarlo al polaco. Es probable también que en esa época se repintara en negro el fondo original (gris y azul celeste) y se resaltaran igualmente en negro algunos elementos de la vestimenta. Los historiadores del arte polacos J. Mycielski (1893) y J. Bołoz-Antoniewicz (1900) fueron los primeros en señalar que podría tratarse del desaparecido retrato de Cecilia Gallerani, joven dama de la corte milanesa que fue amante del duque Ludovico Sforza el Moro. Sabemos que fue retratada por Leonardo por un soneto de Bernardo Bellincioni (1493), poeta de la corte, así como por la correspondencia entre Cecilia e Isabella d’Este (quien en 1498 le pidió prestado su retrato pintado por Leonardo). -

Leonardo in Verrocchio's Workshop

National Gallery Technical Bulletin volume 32 Leonardo da Vinci: Pupil, Painter and Master National Gallery Company London Distributed by Yale University Press TB32 prelims exLP 10.8.indd 1 12/08/2011 14:40 This edition of the Technical Bulletin has been funded by the American Friends of the National Gallery, London with a generous donation from Mrs Charles Wrightsman Series editor: Ashok Roy Photographic credits © National Gallery Company Limited 2011 All photographs reproduced in this Bulletin are © The National Gallery, London unless credited otherwise below. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including BRISTOL photocopy, recording, or any storage and retrieval system, without © Photo The National Gallery, London / By Permission of Bristol City prior permission in writing from the publisher. Museum & Art Gallery: fig. 1, p. 79. Articles published online on the National Gallery website FLORENCE may be downloaded for private study only. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence © Galleria deg li Uffizi, Florence / The Bridgeman Art Library: fig. 29, First published in Great Britain in 2011 by p. 100; fig. 32, p. 102. © Soprintendenza Speciale per il Polo Museale National Gallery Company Limited Fiorentino, Gabinetto Fotografico, Ministero per i Beni e le Attività St Vincent House, 30 Orange Street Culturali: fig. 1, p. 5; fig. 10, p. 11; fig. 13, p. 12; fig. 19, p. 14. © London WC2H 7HH Soprintendenza Speciale per il Polo Museale Fiorentino, Gabinetto Fotografico, Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali / Photo Scala, www.nationalgallery. org.uk Florence: fig. 7, p. -

NAT TURNER's REVOLT: REBELLION and RESPONSE in SOUTHAMPTON COUNTY, VIRGINIA by PATRICK H. BREEN (Under the Direction of Emory

NAT TURNER’S REVOLT: REBELLION AND RESPONSE IN SOUTHAMPTON COUNTY, VIRGINIA by PATRICK H. BREEN (Under the Direction of Emory M. Thomas) ABSTRACT In 1831, Nat Turner led a revolt in Southampton County, Virginia. The revolt itself lasted little more than a day before it was suppressed by whites from the area. Many people died during the revolt, including the largest number of white casualties in any single slave revolt in the history of the United States. After the revolt was suppressed, Nat Turner himself remained at-large for more than two months. When he was captured, Nat Turner was interviewed by whites and this confession was eventually published by a local lawyer, Thomas R. Gray. Because of the number of whites killed and the remarkable nature of the Confessions, the revolt has remained the most prominent revolt in American history. Despite the prominence of the revolt, no full length critical history of the revolt has been written since 1937. This dissertation presents a new history of the revolt, paying careful attention to the dynamic of the revolt itself and what the revolt suggests about authority and power in Southampton County. The revolt was a challenge to the power of the slaveholders, but the crisis that ensued revealed many other deep divisions within Southampton’s society. Rebels who challenged white authority did not win universal support from the local slaves, suggesting that disagreements within the black community existed about how they should respond to the oppression of slavery. At the same time, the crisis following the rebellion revealed divisions within white society. -

A Bird in the Hand Is Worth Two in the Bush

S T Y L E 生活時尚 15 TAIPEI TIMES • WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 4, 2010 EXHIBITIONS Jawshing Arthur Liou, The Insatiable (2010). PHOTO COURTESY OF TAIPEI ARTIST VILLAGE Taipei Artist Village is holding exhibitions by artists who have spent the past few months in their residency program. First up, Taiwan-born, US-based artist Jawshing Arthur Liou (劉肇興) employs video and animation installation to delve into the culinary practices of different cultures in Things That Are Edible (食事). With titles such as Round (圓) and The Insatiable (未央), Liou’s videos are also an ironic look at our gluttonous times. ■ Barry Room, Taipei Artist Village (台北國際 藝術村百里廳), 7 Beiping E Rd, Taipei City (台北市北平東路7號). Open daily from 10am to 7:30pm. Tel: (02) 3393-7377 ■ Opening reception on Saturday at 7pm. Until Aug. 29 Meanwhile, out at Grass Mountain Village, a collective of young photographers called Invalidation Brothers (無效兄弟) — Chiu Chih- A bird in the hand is worth hua (丘智華), Tien Chi-chuan (田季全), Lee Ming-yu (李明瑜) and Lin Cheng-wei (林正偉) — have snapped images of religious rituals with mountain scenes as a backdrop. Entitled Penglai Grass Mountain (蓬萊仙山), these two in the bush black-and-white photos point at the ubiquity of the sacred in our mundane lives. ■ Grass Mountain Artist Village (草山國際藝術 Researchers unveil the ‘holy grail’ of Audubon illustration 村), 92 Hudi Rd, Taipei City (台北市湖底路92號). Open Wednesdays to Sundays from 10am to BY JON HURDLE 4pm. Tel: (02) 2862-2404 REUTERS, PHILADELPHIA ■ Opening reception on Saturday at 11am. Until Sept. 5 esearchers have found the first because it was at a significant turning in the Journal of the Early Republic, in 1825 and its only other branch, in published illustration by John point in his life.” an historical periodical, this fall. -

David Bull Had Two Weeks to Learn Than by DA N IEL GLICK

ON A WHITE FORMICA TABLE IN \'o/hillg (till br either of how much Leonardo's under the National Gallery of Art's con /O'i.'l'ri or/ruted standing of anatomy, optics, light, servation department rested not IlIIles;)" ;t IS flTSt !morew. depth and proportion had one, but two, of the rarest art - Leonardo da \ inci evolved. "Ginevra" appears al- treasures in the Western world: most naive, her eyes lacking portraits by Leonardo da Vinci. Like etherized depth, her full face almost too round, too simply patients on an operating table, two women portrayed. But in rendering the "Lady's" eyes, painted 500 years ago and 15 years apart lay her sideways glance, her delicate face and hand, side by side for the first time-the National Gal Leonardo seems almost to have started with her lery's own exquisite "Ginevra de' Benci" next to skeleton, adding t1esh and clothes only after he the incomparable "Portrait of a Lady With an understood how she was put together, body and Ermine (Cecilia Gallerani)," lent by the Czarto soul. Looking up from the microscope, Bull ryski Museum in Krakow, Poland, for the exhibit grinned like a schoolboy. "You know, I've been "Circa 1492: Art in the Age of Exploration." dying to do this." David Bull, the Gallery's chairman of painting In his 34-year conservation career, the Brit conservation, motioned to his workbench and ish-born Bull has cleaned, restored and exam beamed. "There are the girls," he said, and then ined paintings by Bellini, Titian, Raphael, Rem quickly set to work with his stereomicroscope. -

Or Leonardo Da

GVIR_A_522394.fm Page 382 Saturday, September 18, 2010 1:48 AM 382 Reviews La Bella Principessa: The Story of a New Masterpiece by Leonardo da Vinci (or Leonardo da Vinci “La Bella Principessa”: The Profile Portrait of a Milanese Woman) by Martin Kemp and Pascal Cotte, with contributions by Peter Paul Biro, Eva Schwan, 5 Claudio Strinati, and Nicholas Turner London, Hodder & Stoughton, 2010 208 pp., illustrated, some color, £18.99 (cloth). ISBN: 978-1-444-70626-0 Reviewed by David G. Stork 10 On 30 January 1998, an exceptionally elegant profile portrait of a young woman, executed on vellum in black, red, and white chalk (trois crayon) and highlighted with pen and ink, was purchased at Christie’s auction house for US$21,850. 15 Although it was cataloged “German School, Early 19th Century,” as images of the drawing passed among experts, a few scholars tentatively dared to utter the “L word” and suggest that the portrait was a major discovery: a new work by Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519). 20 This book, by Martin Kemp, an expert on Leonardo and professor of the history of art at Oxford University (recently emeritus), and Pascal Cotte, a founder and director of research at Paris-based Lumière Technology, a firm pioneering the application of high-resolution multispectral imag- ing of art, presents evidence and arguments that the portrait is indeed by Leonardo, 25 and proposes both a date of execution (mid-1490s) as well as the identity of its subject, Bianca Sforza (1482–1496), Duke Ludovico Sforza’s illegitimate daughter. The authors are unequivocal in their conclusion: “With respect to the accumulation of interlocking reasons, we have gathered enough evidence here to confirm that ‘La Bella Principessa’ is indeed by Leonardo” (p. -

La Herencia Recibida 2 Sumario Jueves, 8 De Diciembre De 2011

Nº 763- 8 de diciembre de 2011 - Edición Nacional SEMANARIO CATÓLICO DE INFORMACIÓN Hispanoamérica: 200 años de independencia La herencia recibida 2 Sumario jueves, 8 de diciembre de 2011 LA FOTO 6 3-5 CRITERIOS 7 Etapa II - Número 763 CARTAS 8 Edición Nacional Bicentenario VER, OÍR Y CONTARLO 9 de las Repúblicas AQUÍ Y AHORA iberoamericanas: EDITA: Palacio episcopal de Astorga: Fundación San Agustín. Es hora de hacer Arzobispado de Madrid una lectura justa Arte por dentro y por fuera. 12 de la Historia Cardenal Rouco: DELEGADO EPISCOPAL: Alfonso Simón Muñoz El futuro nos preocupa 13 TESTIMONIO 14 REDACCIÓN: EL DÍA DEL SEÑOR 15 Calle de la Pasa, 3-28005 Madrid. RAÍCES 16-17 Téls: 913651813/913667864 10-11 Fax: 913651188 Leonardo, en la National Gallery: DIreCCIÓN DE INTerNET: Historia de lo visible y lo invible http://www.alfayomega.es 30.000 personas ESPAÑA E-MAIL: sin hogar en España: [email protected] Hace 2012 años, Plan pastoral castrense: tampoco abrieron Un camino para ser fuertes en la fe. 18 DIreCTOR: las puertas al Niño Miguel Ángel Velasco Puente Reformas educativas: REDACTOR JEFE: Ricardo Benjumea de la Vega Es hora de hacer justicia DIreCTOR DE ARTE: a la clase de Religión 19 Francisco Flores Domínguez REDACTOreS: MUNDO Juan Luis Vázquez De la primavera árabe..., Díaz-Mayordomo (Jefe de sección), María Martínez López, a la marea islámica. 20 José Antonio Méndez Pérez, Benedicto XVI: La familia Cristina Sánchez Aguilar, Jesús Colina Díez (Roma) es el camino de la Iglesia 21 SECreTARÍA DE REDACCIÓN: LA VIDA 22-23 Cati Roa Gómez DOCUmeNTACIÓN: 24-25 DESDE LA FE María Pazos Carretero Sínodo de la Iglesia en Asturias: Irene Galindo López INTerNET: Germain Grisez, Un momento de gracia y respuesta. -

{Download PDF} Michelangelo and the Popes Ceiling Ebook, Epub

MICHELANGELO AND THE POPES CEILING PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ross King | 384 pages | 08 May 2006 | Vintage Publishing | 9781844139323 | English | London, United Kingdom Michelangelo and the Pope's Ceiling by Ross King A panorama of illustrious figures converged around the creation of this magnificent work-from the great Dutch scholar Erasmus to the young Martin Luther-and Ross King skillfully weaves them through his compelling historical narrative, offering uncommon insight into the intersection of art and history. Four years earlier, at the age of twenty-nine, Michelangelo had unveiled his masterful statue of David in Florence; however, he had little experience as a painter, even less working in the delicate medium of fresco, and none with the curved surface of vaults, which dominated the chapel's ceiling. The temperamental Michelangelo was himself reluctant, and he stormed away from Rome, risking Julius's wrath, only to be persuaded to eventually begin. Michelangelo would spend the next four years laboring over the vast ceiling. He executed hundreds of drawings, many of which are masterpieces in their own right. Contrary to legend, he and his assistants worked standing rather than on their backs, and after his years on the scaffold, Michelangelo suffered a bizarre form of eyestrain that made it impossible for him to read letters unless he held them at arm's length. Nonetheless, he produced one of the greatest masterpieces of all time, about which Giorgio Vasari, in his Lives of the Artists, wrote, 'There is no other work to compare with this for excellence, nor could there be. Battling against ill health, financial difficulties, domestic problems, inadequate knowledge of the art of fresco, and the pope's impatience, Michelangelo created figures-depicting the Creation, the Fall, and the Flood-so beautiful that, when they were unveiled in , they stunned his onlookers. -

Léonard De Vinci (1452-1519)

1/44 Data Léonard de Vinci (1452-1519) Pays : Italie Langue : Italien Sexe : Masculin Naissance : Anchiano (près de Vinci) (Italie), 15-04-1452 Mort : Amboise (Indre-et-Loire), 02-05-1519 Note : Peintre, sculpteur, architecte. - Théoricien de l'art. - Chercheur scientifique Domaines : Sciences Art Autres formes du nom : Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) (italien) Léonard de Vinci (1452-1519) Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) Da Vinci (1452-1519) Da Vinchi (1452-1519) (japonais) 30 30 30 30 30 30 C0 FB F4 A3 F3 C1 (1452-1519) (japonais) ISNI : ISNI 0000 0001 2124 423X (Informations sur l'ISNI) A dirigé : École de Léonard de Vinci Léonard de Vinci (1452-1519) : œuvres (281 ressources dans data.bnf.fr) Œuvres textuelles (152) Trattato della pittura (1651) Voir plus de documents de ce genre data.bnf.fr 2/44 Data Œuvres iconographiques (63) La Joconde nue Portrait de Christ : peinture parfois attribué à Léonard (1514) de Vinci (1452-1519) (1511) The Burlington House cartoon L'homme vitruvien (1500) (1492) La Vierge aux rochers : National gallery, Londres La Vierge aux rochers : Musée du Louvre (1491) (1483) Il Redentore La Belle princesse : dessin "Tête de vieillard maigre, les lèvres serrées" Codice Corazza de Anne Claude Philippe de Caylus avec Léonard de Vinci (1452-1519) comme Dessinateur du modèle "Tête d'homme aux longs cheveux bouclés, coiffé d'une Codex atlanticus calotte" de Anne Claude Philippe de Caylus avec Léonard de Vinci (1452-1519) comme Dessinateur du modèle "Buste d'un vieux moine" "Combat de divers animaux" de Anne -

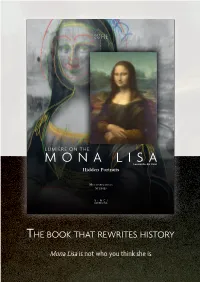

9782954825847.Pdf

Pascal c otte c Pascal otte he Mona Lisa is one of mankind’s great mysteries. With over 9.7 million admirers per year, it is the mostT mythical painting of all time. Thanks to an extraordinary sci- M l entific imagery technique (L.A.M.), this book takes us on a journey UMIÈR into the heart of the paint-layer of the world’s most famous pic- ture and reveals secrets that have remained hidden for 500 years. o e o Mona Lisa is not actually Lisa Gherardini, wife of Francesco del N Giocondo, but a portrait that masks others. Leonardo da Vinci did N t not paint one, but four portraits, super-imposed on one another. H e More than 150 discoveries help us rediscover the painting’s gen- a esis, with Cotte reconstituting the true portrait of Lisa Gherardini – whose face, hairstyle and costume were radically different from those we now see in the Louvre. The book shatters the myth and l alters our vision of the work. It is a giant leap forward in art knowl- edge and art history. Pascal Cotte, who digitized the Mona Lisa at he book reveals that the Mona Lisa is not I the Louvre with his multispectral camera in October 2004, now Lisa Gherardini, wife of Francesco del Giocondo, Leonardo da Vinci sa presents the fruit of ten years’ research. andT that her identity has been mistaken for 500 years. Using a new scientific imaging technique (L.A.M.), Cotte unveils over 150 dis- coveries found beneath all the repaintings. -

Leonardo Da Vinci's Gioconda and the Yellow Shawl Observations On

Knauer:ambrosini 14-02-2010 18:15 Pagina 1 1 LEONARDO DA VINCI’S GIOCONDA AND THE YELLOW SHAWL OBSERVATIONS ON FEMALE PORTRAITS IN THE RENAISSANCE ELFRIEDE R. (KEZIA) KNAUER Dedicated to Almut Mutzenbecher Abstract Interest in Leonardo’s Gioconda – l’illustre incomprise as André Chastel once described her – has ebbed and surged over the years. A high tide is just receding after the publication of a document in 2008 which appeared to settle the question of the sitter’s identity once and for all: a handwritten note in an incun- able, dated 1503, states that the artist has begun to paint a head of “Lise del Giocondo”. For many scholars and certainly for a large public, she is now incontrovertibly the wife of a Florentine silk merchant. However, doubts remain and have been expressed by some experts, if only briefly. In this study I propose to approach the identity of the Gioconda by determining first the social position of the person depicted. By presenting and interpreting distinctive sartorial ele- ment in images of females of Leonardo’s time, we shall reach Knauer:ambrosini 14-02-2010 18:15 Pagina 2 2 Raccolta Vinciana firmer ground on which to proceed. The elements – foremost a shawl – are specifically prescribed in contemporary legal docu- ments as is their color, multiple shades of yellow. The color con- notations are informed by traditions going back to antiquity. The same holds true for certain facial traits and bodily poses of the individuals depicted; they are standardized features that deprive these paintings of the claim to be portraits in the accepted sense yet intentionally add tantalizing touches. -

Life and Religion in the Middle Ages

Life and Religion in the Middle Ages Edited by Flocel Sabaté Life and Religion in the Middle Ages Edited by Flocel Sabaté This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Flocel Sabaté and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7790-5 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7790-9 TABLE OF CONTENTS The Religious Experience, a Mirror of Medieval Society .......................... 1 Flocel Sabaté Building an Identity: King Desiderius, the Abbey of Leno (Brescia), and the Relics of St. Benedict (8th Century) .............................................. 15 Maria Chiara Succurro The Bishopric of Urgell in the Second Half of the 11th Century: Jurisdiction, Convenientiae, Simony ......................................................... 34 Jaume Camats Campabadal Peculiarities of the Bishopric of Urgell in the 10th and 11th Centuries ....... 49 Fernando Arnó-García de la Barrera The Ecclesiastical Policy of the Counts of Barcelona in a Conquered Region: The Relationship between the Counts and the Archbishopric of Tarragona in the 12th and 13th Centuries................................................ 67 Toshihiro Abe The Crisis of Power: Otto IV, Kings of León-Castile, the Cistercian Order ........................................................................................................ 103 Francesco Renzi A Crusader without a Sword: The Sources relating to the Blessed Gerard ...................................................................................................... 125 Giuseppe Perta The Military Orders in Latium ...............................................................