Creative Accounting Practices at Satyam Computers Limited: a Case Study of India’S Enron

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corporate Governance

Corporate Governance T.N. SATHEESH KUMAR Professor DC School of Management and Technology Vagamon, Idukki 1 © Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. 3 YMCA Library Building, Jai Singh Road, New Delhi 110001 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries. Published in India by Oxford University Press © Oxford University Press 2010 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted. Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer. Third-party website addresses mentioned in this book are provided by Oxford University Press in good faith and for information only. -

Asia: Miracle Maker Or Heart Breaker?

ASIA: MIRACLE MAKER OR HEART BREAKER? 14TH Annual Asian Business Conference at the University of Michigan Business School - February 6 & 7, 2004 Page 1 of 73 ASIA: MIRACLE MAKER OR HEART BREAKER? Contents MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRS...................................................................................................................................... 3 MESSAGE FROM THE FACULTY.................................................................................................................................. 4 2004 ORGANIZING COMMITTEE................................................................................................................................ 5 CONFERENCE KEYNOTES............................................................................................................................................... 7 LOGISTICS REPORT ............................................................................................................................................................. 9 ATTENDANCE DEMOGRAPHICS ...............................................................................................................11 DIRECTOR OF MARKETING REPORT ....................................................................................................................12 DIRECTOR OF PANELS REPORT ...............................................................................................................................13 ASEAN PANEL REPORT ...................................................................................................................................14 -

India's Satyam Scandal

Review of Business and Finance Studies Vol. 6, No. 2, 2015, pp. 35-43 ISSN: 2150-3338 (print) ISSN: 2156-8081 (online) www.theIBFR.com INDIA’S SATYAM SCANDAL: EVIDENCE THE TOO LARGE TO INDICT MINDSET OF ACCOUNTING REGULATORS IS A GLOBAL PHENOMENON Kalpana Pai, Texas Wesleyan University Thomas D. Tolleson, Texas Wesleyan University ABSTRACT This paper examines the capture of government regulators using the case of Satyam Computer Services Ltd., one of India’s largest software and services companies, which disclosed a $1.47 billion fraud on its balance sheet on January 7, 2009. The firm, which traded on the New York and Bombay Stock Exchanges, was required to file financial reports with the SEC. Price Waterhouse of India, the local member of PricewaterhouseCoopers (PWC), served as its auditor. After news of the scandal hit the airwaves, Price Waterhouse of India issued a press release and stated that its audit was conducted in accordance with applicable auditing standards and was supported by sufficient audit evidence. Because Satyam shares were quoted on Wall Street, SEC rules prohibited auditors from having business relations with their clients. U.S. regulators failed to take action against PWC. Is this lack of enforcement related to PWC’s size and the impact that the failure of a Big 4 firm would have on the global financial marketplace? We question whether government regulators have been captured by the key market players in the auditing services market. One outcome of this “capture” is moral hazard, which implies that the Big 4 accounting firms, or their local affiliates, may place less emphasis on quality audits. -

Case 1:09-Md-02027-BSJ Document 253 Filed 02/17/11 Page 1 of 163

Case 1:09-md-02027-BSJ Document 253 Filed 02/17/11 Page 1 of 163 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK In re: 09 MD 2027 (BSJ) (Consolidated Action) SATYAM COMPUTER SERVICES LTD. SECURITIES LITIGATION JURY TRIAL DEMANDED This Document A..lies to: All Cases FIRST AMENDED CONSOLIDATED CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT BERNSTEIN LITOWITZ BERGER & GRANT & EISENHOFER P.A ^° ? GROSSMANN,LLP Jay W. Eisenhofer Max W. Berg er Keith M. Fleischman °D• rq Steven B. Singer Mary S. Thomas Bruce Bernstein Deborah A. Elman 1285 Avenue of the Americas, 38th Floor Ananda Chaudhuri New York, NY 10019 485 Lexington Ave., 29th Floor Tel: (212) 554-1400 New York, New York 10017 Fax: (212) 554-1444 Tel: (646) 722-8500 Fax: (646) 722-8501 Co-Lead Counsel for Plaintiffs Co-Lead Counsel for Plaintiffs BARROWAY TOPAZ KESSLER LABATON SUCHAROW LLP MELTZER & CHECK, LLP Joel H. Bernstein David Kessler Louis Gottlieb Sean M. Handler Michael H. Rogers Sharan Nirmul Felicia Y. Mann Christopher L. Nelson 140 Broadway Neena Verma New York, NY 10005 Joshua E. D'Ancona Tel: (212) 907-0700 280 King of Prussia Road Fax: (212) 818-0477 Radnor, PA 19087 Tel: (610) 667-7706 Co-Lead Counsel for Plaintiffs Fax: (610) 667-7056 Co-Lead Counsel for Plaintiffs i' Case 1:09-md-02027-BSJ Document 253 Filed 02/17/11 Page 2 of 163 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. SUMMARY OF THE ACTION 2 II. JURISDICTION & VENUE 7 III. PARTIES AND RELEVANT NON-PARTIES 8 A. Lead Plaintiffs 8 B. Additional Named Plaintiffs 9 C. -

Saji Vettiyil, Et Al. V. Satyam Computer Services Ltd., Et Al. 09-CV-00117

1 Nicole Lavallee (SBN 165755) Email: [email protected] 2 Lesley Ann Hale (SBN 237726) 3 Email:[email protected] BERMAN DeVALERIO 4 425 California Street Suite 2100 5 San Francisco, CA 94104 Telephone: (415) 433-3200 6 Facsimile: (415) 433-6382 7 Christopher J. Keller Alan I. Ellman 8 Stefanie J. Sundel LABATON SUCHAROW LLP 9 140 Broadway New York, New York 10005 10 Telephone: (212) 907-0700 Facsimile: (212) 818-0477 11 Email: [email protected] 12 Attorneys for Mineworkers’ Pension Scheme and Proposed Lead Counsel for the Class 13 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 14 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA SAN JOSE DIVISION 15 16 SAJI VETTIYIL, Individually and on Behalf ) 17 of All Others Similarly Situated, ) )Civil Action No.: C-09-00117 RS 18 Plaintiff, ) )Mag. Judge Richard Seeborg 19 vs. ) ) 20 SATYAM COMPUTER SERVICES, LTD., )Hearing B. RAMALINGA RAJU, B. RAMA RAJU, ) Date: April 22, 2009 21 SRINIVAS VADLAMANI, PRICE ) WATERHOUSE, ) Time: 9:30 A.M. 22 PRICEWATERHOUSECOOPERS ) Courtroom:4 INTERNATIONAL, LTD., ) 23 Defendants. ) 24 ) 25 NOTICE OF FILING MINEWORKERS’ PENSION SCHEME’ MEMORANDUM 26 OF LAW IN FURTHER SUPPORT OF ITS MOTION FOR CONSOLIDATION APPOINTMENT AS LEAD PLAINTIFF, AND APPROVAL OF SELECTION OF 27 LEAD COUNSEL, AND IN OPPOSITION TO THE COMPETING MOTIONS 28 [C-09-00117 RS] NOTICE OF FILING MINEWORKERS’ PENSION SCHEME’ MEMORANDUM OF LAW IN FURTHER SUPPORT OF ITS MOTION FOR CONSOLIDATION APPOINTMENT AS LEAD PLAINTIFF, AND APPROVAL OF SELECTION OF LEAD COUNSEL, AND IN OPPOSITION TO THE COMPETING MOTIONS 1 Mineworkers’ Pension Scheme (“Mineworkers’ Pension”) hereby informs the Court, all 2 parties, and their counsel of record that Mineworkers’ Pension filed on March 26, 2009 in the 3 action entitled Patel v. -

Appendix to Plaintiffs' Motion for Final Approval of Settlement, Plan of Allocation, and Attorneys' Fees

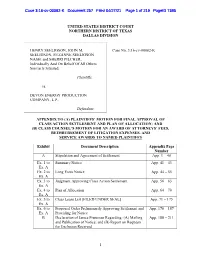

Case 3:16-cv-00082-K Document 257 Filed 04/27/21 Page 1 of 219 PageID 7385 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS DALLAS DIVISION HENRY SEELIGSON, JOHN M. Case No. 3:16-cv-00082-K SEELIGSON, SUZANNE SEELIGSON NASH, and SHERRI PILCHER, Individually And On Behalf Of All Others Similarly Situated, Plaintiffs, vs. DEVON ENERGY PRODUCTION COMPANY, L.P., Defendant. APPENDIX TO (A) PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR FINAL APPROVAL OF CLASS ACTION SETTLEMENT AND PLAN OF ALLOCATION; AND (B) CLASS COUNSEL’S MOTION FOR AN AWARD OF ATTORNEYS’ FEES, REIMBURSEMENT OF LITIGATION EXPENSES, AND SERVICE AWARDS TO NAMED PLAINTIFFS Exhibit Document Description Appendix Page Number A Stipulation and Agreement of Settlement App. 1 – 40 Ex. 1 to Summary Notice App. 41 – 43 Ex. A Ex. 2 to Long Form Notice App. 44 – 55 Ex. A Ex. 3 to Judgment Approving Class Action Settlement App. 56 – 63 Ex. A Ex. 4 to Plan of Allocation App. 64 – 70 Ex. A Ex. 5 to Class Lease List [FILED UNDER SEAL] App. 71 – 175 Ex. A Ex. 6 to Proposed Order Preliminarily Approving Settlement and App. 176 – 187 Ex. A Providing for Notice B Declaration of James Prutsman Regarding: (A) Mailing App. 188 – 211 and Publication of Notice; and (B) Report on Requests for Exclusion Received 1 Case 3:16-cv-00082-K Document 257 Filed 04/27/21 Page 2 of 219 PageID 7386 C Declaration of Joseph H. Meltzer in Support of Class App. 212 – 265 Counsel’s Motion for An Award of Attorneys’ Fees Filed on Behalf of Kessler Topaz Meltzer & Check LLP D Declaration of Brad Seidel in Support of Class App. -

What Went Wrong with Satyam?

WHAT WENT WRONG WITH SATYAM? PROFESSOR J. P. SHARMA J.P Sharma, Professor of Law & Corporate governance, Department of Commerce, Delhi School of Economics, University of Delhi WHAT WENT WRONG WITH SATYAM? INTRODUCTION Till about two decades ago corporate governance was relatively an unknown subject. The subject came into prominence in the late 80’s and early 90’s when the corporate sector in many countries was surrounded with problems of questionable corporate policies or unethical practices. Junk Bond fiasco of USA and failure of Maxwell, BCCI and Polypeck in UK resulted in the beginning of codes and standards on corporate governance. The USA, UK and number of other developed countries reacted strongly to the corporate failures and codes & standards on corporate governance came to the centre stage. Enron debacle in 2001 and number of other scandals involving large US companies such as the Tyco, Quest, Global Crossings, the World.Com and the exposure of auditing lacunae, which led to the collapse of the Andersen, triggered the reform process and resulted in the passing of the Public Accounting Reform and Investor Protection Act of 2002 known as Sarbanes- Oxley (SOX) Act, 2002 in USA. BACKGROUND On 24th June 1987, Satyam Computer Services Ltd (Popularly known as Satyam) was incorporated by the two brothers, B Rama Raju and B Ramalinga Raju 1, as a private limited company with just 20 employees for providing software development and consultancy services to large corporations (the company got converted into public in 1991). During the year 1996, company promoted four subsidiaries including Satyam Renaissance Consulting Ltd, Satyam Enterprise Solutions Pvt. -

172 Satyam Scam: Lessons for Corporate Governance

IJRESS Volume 2, Issue 12(December 2012) (ISSN 2249-7382) Satyam scam: Lessons for Corporate Governance * Dr Vijay prakash **Monika Srivastava ABSTRACT The Satyam scandal dubbed as India’s Enron is one of the largest accounting frauds in the country’s corporate history. B.Ramalinga Raju, founder and chairman of Satyam Computer Services Ltd., the fourth leading IT services firm, declared on January 7, 2009 that his company had been faking its accounts for years, exaggerating revenues and overstating profits by $1billion. This article examines the Satyam scandal and explains what happened, why and who is to blame. Satyam’s emergence from a local to a global traded conglomerate is traced, followed by the events in the aftermath of the scandal. The paper concludes with the proposed regulatory prescriptions encapsulated by the new code created by India’s Ministry of Corporate Affairs, with suggestions proposed by the Parliamentary Standing Committee. These prescriptions are likely to be introduced in the impending Budget session of Parliament .They relate to the functioning of independent directors, enhanced pace of disclosures, conduct of audit and improved transparency in governance mechanisms. Keywords: Corporate Governance, Satyam Computer Services Ltd., Price Waterhouse, scandal Introduction By Ramalinga Raju , founder and chairman of Satyam Computer Services Ltd., saying publicly on January 7 2009, that his firm had been misrepresenting revenues and overstating profits by $1billion,is a case of corporate mis-governance and accounting malpractice. Specifically, Ramalinga Raju(Raju) admitted that Satyam’s balance sheet included .7,136 crore(almost $1.5billion) in non-existent cash and bank balances, accumulated interest and misstatements. -

Anti-Corruption Guidelines (“Toolkit”) for MBA Curriculum Change July 2012

Anti-corruption guidelines (“Toolkit”) for MBA curriculum change July 2012 A project by the Anti-Corruption Working Group of the Principles for Responsible Management Education (PRME) initiative, United Nations Global Compact Contents Foreword ........................................................................................................................................................... 3 Overview ........................................................................................................................................................... 4 How to Use this Toolkit ..................................................................................................................................... 8 1. Core Concepts ............................................................................................................................................. 9 2. Economics, Market Failure and Professional Dilemmas........................................................................... 16 3. Legislation, Control by Law, Agency and Fiduciary Duty .......................................................................... 18 4. Why Corruption: Behavioral Issues .......................................................................................................... 21 5. Conflicts of Interest .................................................................................................................................. 27 6. International Standards and Supply Chain .............................................................................................. -

Essays on the Financial Crisis and Globalization Introduction

Essays on the Financial Crisis and Globalization Nirvikar Singh Professor of Economics University of California, Santa Cruz September 2009 Introduction We have certainly been living in interesting times. While avoiding the worst connotations of that concept (no global war or other catastrophe), we have seen the fall of communism, the rise of information technology, and the beginnings of a shift in the global economic balance, back toward the days before the industrial revolution, when Asia carried as much economic and political weight as the West. All three trends – the ostensible triumph of capitalism, the innovations wrought by digital technologies, and the growth of China and (to some extent) India – in some ways came to a head in the current financial crisis. The crisis was sudden, and at one stage seemed that it would engulf the world economy in depression and even chaos. It prompted some fevered writing, by journalists in particular. For my part, writing fortnightly columns for Indian financial dailies (first the Financial Express, then The Mint), I have seen my role as bringing analytical economic thought to bear on understanding current events. A column gives one some freedom to opine, but also imposes disciplines of concision and clarity, beyond the usual requirements of academia. The following dozen pieces were written between September 2007 and April 2009. They comment on the reasons for the crisis, and possible solutions, using economic theory to understand the issues wherever possible, but in relatively non-technical language. What keeps markets working well? What do financial markets accomplish, at a fundamental level? Why do markets fail? Why do scandals arise? What can regulators do to improve matters? I have tried to shed light on these basic questions in the context of current events. -

United States District Court Eastern District of Texas Sherman Division

Case 4:17-cv-00449-ALM Document 283-1 Filed 04/15/20 Page 1 of 69 PageID #: 12098 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS SHERMAN DIVISION OKLAHOMA LAW ENFORCEMENT Case No. 4:17-CV-0449-ALM RETIREMENT SYSTEM, Individually And On Behalf Of All Others Similarly Situated, Judge Amos L. Mazzant, III Plaintiff, vs. ADEPTUS HEALTH INC., et al., Defendants. JOINT DECLARATION OF JEREMY P. ROBINSON AND RICHARD A. RUSSO, JR. IN SUPPORT OF: (A) PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR FINAL APPROVAL OF CLASS ACTION SETTLEMENT AND PLAN OF ALLOCATION; AND (B) LEAD COUNSEL’S MOTION FOR AN AWARD OF ATTORNEYS’ FEES AND LITIGATION EXPENSES Case 4:17-cv-00449-ALM Document 283-1 Filed 04/15/20 Page 2 of 69 PageID #: 12099 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 1 II. HISTORY AND PROSECUTION OF THE ACTION .......................................................... 7 A. Adeptus Declares Bankruptcy............................................................................... 10 B. Lead Plaintiffs and Lead Counsel Are Appointed and Continue Their Extensive Investigation ......................................................................................... 11 C. Overview and Filing of the Complaint ................................................................. 13 D. Defendants’ Extensive Motions to Dismiss the CAC ........................................... 14 E. The Court’s Opinion Largely Denying Defendants’ Motions to Dismiss and the Start of -

Trio Fraud Manual.Pdf

Trio Fraud Manual Victims of Financial Fraud (VOFF Inc) January 2018 VOFF’s response to ASIC’s failures concerning the disappearance of superannuation and investment savings from the Australian financial system ASIC say there are no unresolved issues around the Trio Capital Limited fraud. VOFF strongly disagree. ASIC’s website states that its role is, ‘…. an independent Commonwealth Government body. We are set up under and administer the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (ASIC Act), and we carry out most of our work under the Corporations Act 2001 (Corporations Act). VOFF allege that in regards to the largest superannuation fraud in Australian history, ASIC was directed by the office of Minister of Superannuation, Bill Shorten to prosecute the financial advisor that had recommended Trio products to the Australian Workers Union ‘slush fund’. Little attention was paid to the international architects of the Trio fraud while much attention was placed on Enforceable Undertakings. John Telford Secretary VOFF Inc Email: [email protected] Thank you VOFF Inc members, • Jenny Butler and • Andrew Grey For reviewing, editing and guidance in writing this document. Also thank you to my neighbour for offering a layperson perspective. Content Abbreviations -------------------------------------------------------------------------------page 3 Reference – people -------------------------------------------------------------------------page 4 Trio Fraud – a brief summary ------------------------------------------------------------page