Business Ethics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(A) Bond Plaintiffs' Motion

Case 1:08-cv-09522-SHS Document 160 Filed 06/07/13 Page 1 of 89 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK IN RE CITIGROUP INC. BOND LITIGATION Master File No. 08 Civ. 9522 (SHS) ECF Case DECLARATION OF STEVEN B. SINGER IN SUPPORT OF: (I) BOND PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR FINAL APPROVAL OF CLASS ACTION SETTLEMENT AND PLAN OF ALLOCATION, AND (II) BOND COUNSEL’S MOTION FOR AN AWARD OF ATTORNEYS’ FEES AND REIMBURSEMENT OF LITIGATION EXPENSES Case 1:08-cv-09522-SHS Document 160 Filed 06/07/13 Page 2 of 89 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 1 II. PROSECUTION OF THE ACTION .................................................................................. 4 A. Bond Counsel’s Efforts to Identify and Preserve the Claims of Investors in Citigroup’s Bonds and Preferred Stock .................................................................. 4 B. Preparation of the Consolidated Amended Class Action Complaint, and Summary of the Claims Asserted ........................................................................... 6 C. The Citigroup Defendants’ and the Underwriter Defendants’ Extensive Motions to Dismiss ............................................................................................... 12 D. The Court’s Opinions Largely Denying Defendants’ Motions to Dismiss, and Denying Defendants’ Motion for Reconsideration ........................................ 15 E. Bond Plaintiffs Conduct Extensive Discovery and Motion Practice -

Corporate Governance

Corporate Governance T.N. SATHEESH KUMAR Professor DC School of Management and Technology Vagamon, Idukki 1 © Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. 3 YMCA Library Building, Jai Singh Road, New Delhi 110001 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries. Published in India by Oxford University Press © Oxford University Press 2010 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted. Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer. Third-party website addresses mentioned in this book are provided by Oxford University Press in good faith and for information only. -

Asia: Miracle Maker Or Heart Breaker?

ASIA: MIRACLE MAKER OR HEART BREAKER? 14TH Annual Asian Business Conference at the University of Michigan Business School - February 6 & 7, 2004 Page 1 of 73 ASIA: MIRACLE MAKER OR HEART BREAKER? Contents MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRS...................................................................................................................................... 3 MESSAGE FROM THE FACULTY.................................................................................................................................. 4 2004 ORGANIZING COMMITTEE................................................................................................................................ 5 CONFERENCE KEYNOTES............................................................................................................................................... 7 LOGISTICS REPORT ............................................................................................................................................................. 9 ATTENDANCE DEMOGRAPHICS ...............................................................................................................11 DIRECTOR OF MARKETING REPORT ....................................................................................................................12 DIRECTOR OF PANELS REPORT ...............................................................................................................................13 ASEAN PANEL REPORT ...................................................................................................................................14 -

India's Satyam Scandal

Review of Business and Finance Studies Vol. 6, No. 2, 2015, pp. 35-43 ISSN: 2150-3338 (print) ISSN: 2156-8081 (online) www.theIBFR.com INDIA’S SATYAM SCANDAL: EVIDENCE THE TOO LARGE TO INDICT MINDSET OF ACCOUNTING REGULATORS IS A GLOBAL PHENOMENON Kalpana Pai, Texas Wesleyan University Thomas D. Tolleson, Texas Wesleyan University ABSTRACT This paper examines the capture of government regulators using the case of Satyam Computer Services Ltd., one of India’s largest software and services companies, which disclosed a $1.47 billion fraud on its balance sheet on January 7, 2009. The firm, which traded on the New York and Bombay Stock Exchanges, was required to file financial reports with the SEC. Price Waterhouse of India, the local member of PricewaterhouseCoopers (PWC), served as its auditor. After news of the scandal hit the airwaves, Price Waterhouse of India issued a press release and stated that its audit was conducted in accordance with applicable auditing standards and was supported by sufficient audit evidence. Because Satyam shares were quoted on Wall Street, SEC rules prohibited auditors from having business relations with their clients. U.S. regulators failed to take action against PWC. Is this lack of enforcement related to PWC’s size and the impact that the failure of a Big 4 firm would have on the global financial marketplace? We question whether government regulators have been captured by the key market players in the auditing services market. One outcome of this “capture” is moral hazard, which implies that the Big 4 accounting firms, or their local affiliates, may place less emphasis on quality audits. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

MIT Admissions Spoof Webpage

About MIT When I attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), it was the greatest technology university in the world, of all time, particularly in Information Technology (IT), which includes cybersecurity. Now it has been taken over by those who don't care about its technological greatness, many nonMIT alum, and only want to use it to forward their leftist liberal political agenda. An organization is only as good, or as bad, as those who lead it, so let's meet some of MIT's leaders. Along the way, why this is the MIT Admissions page will be explained. Leo Rafael Reif, MIT President In the late 1930's Reif's parents, Eastern European Jews, fled the Nazis to Venezuela. Reif is not an MIT alum. He was educated in the thirdrate education system of Venezuela and in California, both where he was heavily indoctrinated into leftist ideology. While nothing could force him to return to the hellhole that is Venezuela, he still embraces the leftist ideology of Venezuela's destroyer Hugo Chavez. After I was at MIT, it decided to pick its president based only on a penis and pigmentation check and picked nonMITalum Susan Hockfield to meet this newfound singular agenda of diversity. After she resigned (and Reif knows why), next on the diversity checklist was an AfricanAmerican or Hispanic. Reif didn't think he could pass for AfricanAmerican so, borrowing a scam from nonNative American Elizabeth Warren, he pretended to be Hispanic and became MIT President. (I took high school Spanish but that doesn't make me Hispanic.) Too bad for all those real AfricanAmerican and Hispanic MIT alum. -

Stock Market Participation in the Aftermath of an Accounting Scandal

Stock market participation in the aftermath of an accounting scandal Renuka Sane∗ National Institute of Public Finance and Policy June 2017 Abstract In this paper we study the impact on investor behaviour of fraud revelation. We ask if investors with direct exposure to stock market fraud (treated investors) are more likely to decrease their participation in the stock market than investors with no direct exposure to fraud (control investors)? Using daily investor account holdings data from the National Stock Depository Limited (NSDL), the largest depository in India, we find that treated investors cash out almost 10.6 percentage points of their overall portfolio relative to control investors post the crisis. The cashing out is largely restricted to the bad stock. Over the period of a month, there is no difference in the trading behaviour of the treated and control investors. These results are contrary to those found in mature economies. ∗I thank Jayesh Mehta, Tarun Ramadorai, Ajay Shah, K. V. Subramaniam, Susan Thomas, Harsh Vardhan, participants of the IGIDR Emerging Markets Conference, 2016, NSE-NYU conference, 2016, for useful comments. Anurag Dutt provided excellent research assistance. I thank the NSE-NYU initiative on financial markets for funding support, and Finance Research Group, IGIDR for access to data. 1 Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 Data 5 2.1 Sample . .7 3 Research design 8 3.1 The Satyam fraud . .8 3.2 The matching framework . 11 3.3 Main outcome of interest . 13 3.4 Difference-in-difference . 16 4 Results 16 4.1 Effect on cashing out of portfolio . 16 4.2 Effect on cashing out Satyam . -

Case 1:09-Md-02027-BSJ Document 253 Filed 02/17/11 Page 1 of 163

Case 1:09-md-02027-BSJ Document 253 Filed 02/17/11 Page 1 of 163 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK In re: 09 MD 2027 (BSJ) (Consolidated Action) SATYAM COMPUTER SERVICES LTD. SECURITIES LITIGATION JURY TRIAL DEMANDED This Document A..lies to: All Cases FIRST AMENDED CONSOLIDATED CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT BERNSTEIN LITOWITZ BERGER & GRANT & EISENHOFER P.A ^° ? GROSSMANN,LLP Jay W. Eisenhofer Max W. Berg er Keith M. Fleischman °D• rq Steven B. Singer Mary S. Thomas Bruce Bernstein Deborah A. Elman 1285 Avenue of the Americas, 38th Floor Ananda Chaudhuri New York, NY 10019 485 Lexington Ave., 29th Floor Tel: (212) 554-1400 New York, New York 10017 Fax: (212) 554-1444 Tel: (646) 722-8500 Fax: (646) 722-8501 Co-Lead Counsel for Plaintiffs Co-Lead Counsel for Plaintiffs BARROWAY TOPAZ KESSLER LABATON SUCHAROW LLP MELTZER & CHECK, LLP Joel H. Bernstein David Kessler Louis Gottlieb Sean M. Handler Michael H. Rogers Sharan Nirmul Felicia Y. Mann Christopher L. Nelson 140 Broadway Neena Verma New York, NY 10005 Joshua E. D'Ancona Tel: (212) 907-0700 280 King of Prussia Road Fax: (212) 818-0477 Radnor, PA 19087 Tel: (610) 667-7706 Co-Lead Counsel for Plaintiffs Fax: (610) 667-7056 Co-Lead Counsel for Plaintiffs i' Case 1:09-md-02027-BSJ Document 253 Filed 02/17/11 Page 2 of 163 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. SUMMARY OF THE ACTION 2 II. JURISDICTION & VENUE 7 III. PARTIES AND RELEVANT NON-PARTIES 8 A. Lead Plaintiffs 8 B. Additional Named Plaintiffs 9 C. -

Saji Vettiyil, Et Al. V. Satyam Computer Services Ltd., Et Al. 09-CV-00117

1 Nicole Lavallee (SBN 165755) Email: [email protected] 2 Lesley Ann Hale (SBN 237726) 3 Email:[email protected] BERMAN DeVALERIO 4 425 California Street Suite 2100 5 San Francisco, CA 94104 Telephone: (415) 433-3200 6 Facsimile: (415) 433-6382 7 Christopher J. Keller Alan I. Ellman 8 Stefanie J. Sundel LABATON SUCHAROW LLP 9 140 Broadway New York, New York 10005 10 Telephone: (212) 907-0700 Facsimile: (212) 818-0477 11 Email: [email protected] 12 Attorneys for Mineworkers’ Pension Scheme and Proposed Lead Counsel for the Class 13 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 14 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA SAN JOSE DIVISION 15 16 SAJI VETTIYIL, Individually and on Behalf ) 17 of All Others Similarly Situated, ) )Civil Action No.: C-09-00117 RS 18 Plaintiff, ) )Mag. Judge Richard Seeborg 19 vs. ) ) 20 SATYAM COMPUTER SERVICES, LTD., )Hearing B. RAMALINGA RAJU, B. RAMA RAJU, ) Date: April 22, 2009 21 SRINIVAS VADLAMANI, PRICE ) WATERHOUSE, ) Time: 9:30 A.M. 22 PRICEWATERHOUSECOOPERS ) Courtroom:4 INTERNATIONAL, LTD., ) 23 Defendants. ) 24 ) 25 NOTICE OF FILING MINEWORKERS’ PENSION SCHEME’ MEMORANDUM 26 OF LAW IN FURTHER SUPPORT OF ITS MOTION FOR CONSOLIDATION APPOINTMENT AS LEAD PLAINTIFF, AND APPROVAL OF SELECTION OF 27 LEAD COUNSEL, AND IN OPPOSITION TO THE COMPETING MOTIONS 28 [C-09-00117 RS] NOTICE OF FILING MINEWORKERS’ PENSION SCHEME’ MEMORANDUM OF LAW IN FURTHER SUPPORT OF ITS MOTION FOR CONSOLIDATION APPOINTMENT AS LEAD PLAINTIFF, AND APPROVAL OF SELECTION OF LEAD COUNSEL, AND IN OPPOSITION TO THE COMPETING MOTIONS 1 Mineworkers’ Pension Scheme (“Mineworkers’ Pension”) hereby informs the Court, all 2 parties, and their counsel of record that Mineworkers’ Pension filed on March 26, 2009 in the 3 action entitled Patel v. -

I Was on a Panel Discussion with Fred Hargadon, the Retired Former Dean

Don't Do Anything That Will Kill You Yet Another College Guide by Scott White Version 1.5 (c) 2012 by Scott White PRE-PUBLICATION REVIEW COPY The author requests your comments, edits, amplifications, endorsements and suggestions. Scott can be reached at: [email protected] Pre-Publication Review Copy 2 (c) 2012 Scott White This book is dedicated to Eve, Kira, Zachary and Benjamin. They are the lights of my life. Pre-Publication Review Copy 3 (c) 2012 Scott White Dear reader, This is NOT the book I really want to write. This book is called Don’t Do Anything That Can Kill You – Yet Another College Guide, I want to write Don’t Do Anything That Can Kill You – NOT Another College Guide. The world does not need another college guide; there are too many already. Please read this letter before the book because I want to tell you what this book is, why it is the way it is, what I hope to develop instead, and how you can help make that happen. The first half of this book contains essays that present my perspective on the college application process, and suggests attitudes you might adopt too. The second half contains a collection of reference materials that I hand out to students and their parents. I think all of it is useful although some of it is out-of-date. I am not sure I’d want to include this in the book I really want to write because it can be found elsewhere. It is in this edition because that way I can just give this book to my students rather than a loose collection of articles. -

Appendix to Plaintiffs' Motion for Final Approval of Settlement, Plan of Allocation, and Attorneys' Fees

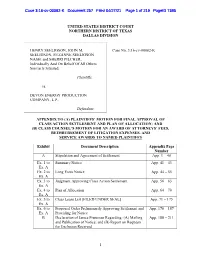

Case 3:16-cv-00082-K Document 257 Filed 04/27/21 Page 1 of 219 PageID 7385 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS DALLAS DIVISION HENRY SEELIGSON, JOHN M. Case No. 3:16-cv-00082-K SEELIGSON, SUZANNE SEELIGSON NASH, and SHERRI PILCHER, Individually And On Behalf Of All Others Similarly Situated, Plaintiffs, vs. DEVON ENERGY PRODUCTION COMPANY, L.P., Defendant. APPENDIX TO (A) PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR FINAL APPROVAL OF CLASS ACTION SETTLEMENT AND PLAN OF ALLOCATION; AND (B) CLASS COUNSEL’S MOTION FOR AN AWARD OF ATTORNEYS’ FEES, REIMBURSEMENT OF LITIGATION EXPENSES, AND SERVICE AWARDS TO NAMED PLAINTIFFS Exhibit Document Description Appendix Page Number A Stipulation and Agreement of Settlement App. 1 – 40 Ex. 1 to Summary Notice App. 41 – 43 Ex. A Ex. 2 to Long Form Notice App. 44 – 55 Ex. A Ex. 3 to Judgment Approving Class Action Settlement App. 56 – 63 Ex. A Ex. 4 to Plan of Allocation App. 64 – 70 Ex. A Ex. 5 to Class Lease List [FILED UNDER SEAL] App. 71 – 175 Ex. A Ex. 6 to Proposed Order Preliminarily Approving Settlement and App. 176 – 187 Ex. A Providing for Notice B Declaration of James Prutsman Regarding: (A) Mailing App. 188 – 211 and Publication of Notice; and (B) Report on Requests for Exclusion Received 1 Case 3:16-cv-00082-K Document 257 Filed 04/27/21 Page 2 of 219 PageID 7386 C Declaration of Joseph H. Meltzer in Support of Class App. 212 – 265 Counsel’s Motion for An Award of Attorneys’ Fees Filed on Behalf of Kessler Topaz Meltzer & Check LLP D Declaration of Brad Seidel in Support of Class App. -

Report on Research Project of Financial Scams in India

REPORT ON RESEARCH PROJECT OF FINANCIAL SCAMS IN INDIA Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement of the Masters in Business Administration Programme Offered by Jain University during the year 2013-14 BY MOHAMMED MAAZ 3rd Semester MBA UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF PROF.SHRUTI AGARWAL # 319, 17th Cross, 25th Main, JP Nagar 6th Phase Bangalore – 560 078 Phone : 080-43430400, Fax : 080-26532730 E-mail : [email protected], Website : www.bschool.cms.ac.in Declaration I, hereby declare that this Lab Hours / Project (Research Project) on FINANCIAL SCAMS IN INDIA is prepared by me during the academic year 2014-15 under the guidance of prof. Shruti Agarwal. I also declare that this project which is the partial fulfillment of the requirement for MBA programme Offered by Jain University, it is the result of my own efforts with the help of experts. Name : MOHAMMED MAAZ Sem : 3rd Sec : “C” Reg.No : 13MBA63049 Date : Place : Signature ACKNOWLEDGEMENT It gives me immense pleasure in presenting the project report on Financial Scams in India Firstly, I take the opportunity in thanking almightily and my parents without whose continuous blessings, I would not have been able to complete this project. I would like to thank my project guide Prof. Shruti Agarwal for her great help, valuable opinions, advice and suggestions in fulfillment of this project. I am also grateful to Prof. Durga Praveena for encouraging me to select the project topic. I am thankful to our college for all the possible assistance and support, by making available the required books and the internet room which have proved useful to me in successfully completing my project.