Identity and Revision in Trungpa Rinpoche's Buddhism(S)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gongchik Teachings with Khenpo Tsultrim Tenzin Rinpoche At

GongChik Teachings with Khenpo Tsultrim Tenzin Rinpoche At Drikung Kyobpa Choling Saturday and Sunday June 9 th and 10 th 10am to 5pm Khenpo Tsultrim Rinpoche took his monk's vows at the age of 14. He studied the Thirteen Major Texts with Khenchen Nawang Gyalpo Rinpoché and other khenpo s. He also received the entire Lamdré -cycle of empowerments of the Ngor-Sakya lineage from Khensur Khenchen Rinpoché and from Amdo Lama Togden Rinpoché and Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoché. He also received many other Nyingma empowerments and teachings. Later, Khenpo Rinpoché joined Drikung Kagyu Institute at Jangchub Ling in Dehra Dun and there met His Holiness Drikung Kyabgön Chetsang Rinpoché. The spontaneous devotion he felt for His Holiness resulted in his request to His Holiness to join the monastery there and continue his education. Having already completed the first four years of his studies at other monasteries, Khenpo Rinpoché quickly completed his education at Jangchub Ling. After three years teaching lower classes in the monastic college, he was enthroned by His Holiness Drikung Kyabgön Chetsang Rinpoché as as a "Khenpo" in 1998, and spent three more years teaching Buddhist philosophy at the Institute. Additionally, Khenpo Rinpoché completed Ngondro, Cakrasamvara and other practices while in retreat. In April, 2001, Khenpo Rinpoché arrived at the Tibetan Meditation Center in Maryland and has been teaching there and at other locations across the United States. Khenpo was appointed the co- spiritual director of the Tibetan Meditation Center in Maryland by Khenchen Gyaltshen Rinpoché. Khenpo Tsultrim is known and loved for his engaging teaching style as well as his complete lack of pretensions. -

Karmapa Karma Pakshi (1206-1283)

CUỘC ĐỜI SIÊU VIỆT CỦA 16 VỊ TỔ KARMAPA TÂY TẠNG Biên soạn: Karma Thinley Rinpoche Nguyên tác: The History of Sixteen Karmapas of Tibet Karmapa Rangjung Rigpe Dorje XVI Karma Thinley Rinpoche - Việt dịch: Nguyễn An Cư Thiện Tri Thức 2543-1999 THIỆN TRI THỨC MỤC LỤC LỜI NÓI ĐẦU ............................................................................................ 7 LỜI TỰA ..................................................................................................... 9 DẪN NHẬP .............................................................................................. 12 NỀN TẢNG LỊCH SỬ VÀ LÝ THUYẾT ................................................ 39 Chương I: KARMAPA DUSUM KHYENPA (1110-1193) ...................... 64 Chương II: KARMAPA KARMA PAKSHI (1206-1283) ......................... 70 Chương III: KARMAPA RANGJUNG DORJE (1284-1339) .................. 78 Chương IV: KARMAPA ROLPE DORJE (1340-1383) ........................... 84 Chương V: KARMAPA DEZHIN SHEGPA (1384-1415) ........................ 95 Chương VI: KARMAPA THONGWA DONDEN (1416-1453) ............. 102 Chương VII: KARMAPA CHODRAG GYALTSHO (1454-1506) ........ 106 Chương VIII: KARMAPA MIKYO DORJE (1507-1554) ..................... 112 Chương IX: KARMAPA WANGCHUK DORJE (1555-1603) .............. 122 Chương X: KARMAPA CHOYING DORJE (1604-1674) .................... 129 Chương XI: KARMAPA YESHE DORJE (1676-1702) ......................... 135 Chương XII: KARMAPA CHANGCHUB DORJE (1703-1732) ........... 138 Chương XIII: KARMAPA DUDUL DORJE (1733-1797) .................... -

Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism, Revised Edition

REVISED EDITION John Powers ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 1 Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 2 ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 3 Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism revised edition by John Powers Snow Lion Publications ithaca, new york • boulder, colorado ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 4 Snow Lion Publications P.O. Box 6483 • Ithaca, NY 14851 USA (607) 273-8519 • www.snowlionpub.com © 1995, 2007 by John Powers All rights reserved. First edition 1995 Second edition 2007 No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means without prior written permission from the publisher. Printed in Canada on acid-free recycled paper. Designed and typeset by Gopa & Ted2, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Powers, John, 1957- Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism / by John Powers. — Rev. ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN-13: 978-1-55939-282-2 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-55939-282-7 (alk. paper) 1. Buddhism—China—Tibet. 2. Tibet (China)—Religion. I. Title. BQ7604.P69 2007 294.3’923—dc22 2007019309 ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 5 Table of Contents Preface 11 Technical Note 17 Introduction 21 Part One: The Indian Background 1. Buddhism in India 31 The Buddha 31 The Buddha’s Life and Lives 34 Epilogue 56 2. Some Important Buddhist Doctrines 63 Cyclic Existence 63 Appearance and Reality 71 3. Meditation 81 The Role of Meditation in Indian and Tibetan Buddhism 81 Stabilizing and Analytical Meditation 85 The Five Buddhist Paths 91 4. -

YEAR 6/2019 KAGYU SAMYE LING: Meditation

YEAR 6/2019 KAGYU SAMYE LING: meditation & yoga retreat – with cat & phil Eskdalemuir, Dumfriesshire, Scotland Kagyu Samye Ling - tibetan buddhist centre/kagyu tradition Thursday, 8th – Sunday, 11th August 2019 Cost: £350 tuition (includes donation to Kagyu Samye Ling) This is an additional way we have chosen to support the monastery & their ongoing charitable work. Accommodation to be booked directly with Samye Ling. Deposit: £200 to hold a space – (FULL CAPACITY – PREVIOUS YEARS) Balance due: 8th June (two months prior) – NO REFUNDS AFTER THIS DATE Payment methods: cash/cheque/bank transfer Cheques made out to: Catherine Alip-Douglas Bank transfer to: TSB – Bayswater Branch, 30-32 Westbourne Grove sort code: 309059, account number:14231860, Swift/BIC code: IBAN:GB49TSBS30905914231860 BIC: TSBSGB2AXXX The Retreat: 3 nights/4 days includes a tour of samye ling, daily yoga sessions (2- 2.5hours), lectures, meditation practice with Samye Ling’s sangha, a film screening of “AKONG” based on Akong Rinpoche, one of the founders of KSL and informal gatherings in an environment conducive to a proper ‘retreat’. As always, this retreat is also part of the Sangyé Yoga School's 2019 TT. There will be time for walks in the beautiful surroundings and reading books from their well-stocked and newly expanded gift shop. NOT INCLUDED: accommodation (many options depending on your budget) & travel. Kagyu Samye Ling provides the perfect environment to reconnect with nature, go deeper in your meditation practice, learn about the foundations of Tibetan Buddhism and the Kagyu lineage. It is a simple retreat for students who want to get to the heart of a practice and spend more time than usual in meditation sessions. -

Biography of Khenpo Sherab Sangpo (PDF)

BIOGRAPHY Khenpo Sherab Sangpo Khenpo Sherab Sangpo studied under the lord of refuge Khenchen Padma Tsewang Rinpoche…and with numerous masters of all traditions. He has taught the profound Dharma of sutra and mantra to students of numerous nationalities. This teacher should be treated with reverence and respect. Doing so will bring goodness in this life and the next and establish a profound connection with the Buddha’s teachings. —Katok Getsé Rinpoche Khenpo Sherab Sangpo began his studies in Tibet with the famed master Petsé Rinpoche (Khenchen Padma Tsewang), with whom he studied for over twenty years. He became a monk at the age of seven at Gyalwa Phukhang Monastery, a branch of Dilgo Khyentsé Rinpoche’s Shechen Monastery. Under Petsé Rinpoche's guidance, he first studied Tibetan Buddhist ritual, eventually becoming one of the monastery's ritual leaders and chant masters. Even at a young age, he was renowned for his ability to memorize the vast number of texts used at the monastery and his command of Tibetan Buddhist ritual. Recognizing his great potential, Petsé Rinpoche enrolled his student in the monastery’s monastic college, Ngedön Shedrup Targyé Ling, when he was only thirteen years old. For years, the only task his master gave him was to memorize the countless texts that form the core of the Buddhist education system. Only once he had memorized them all and could recite them from memory did he go on to receive teachings on their meaning. A tireless teacher, Petsé Rinpoche often taught day after day for months on end, without taking a single day off. -

Toy-Fung Tung

TOY-FUNG TUNG Assistant Professor, English Department John Jay College of Criminal Justice, CUNY 524 West 59th Street New York, New York 10019 212-237-8705; [email protected] Education Ph.D. Comparative Literature (medieval), Columbia University, 2005 Thesis: Chrétien de Troyes and Historia: In Fiction's Mirror Sponsor: Professor Joan M. Ferrante Languages: Latin; French and German (modern and medieval) M.Phil. English and Comparative Literature (medieval and early modern), Columbia University M.A. English and Comparative Literature, Columbia University Thesis: Petrarch’s Canzoniere and Scève’s Délie B.A. English and French, Barnard College Publications “Of Adam’s Rib, Cannibalism, and the Construction of Otherness through Natural Law.” In Theorizing Legal Personhood in Late Medieval England, edited by Andreea D. Boboc and Kathleen E. Kennedy, (8903 words). Leiden: Brill, 2013 (accepted). “Mind, Awareness, and Causality: Poetic Language in the Medieval Philosophy of Śāntaraksita's Svātantrika-Prāsangika and Longchenpa's Great Perfection.” In Studies on Śāntaraksita’s Yogācāra-Madhyamaka, edited by Marie-Louise Friquegnon and Noé Dinnerstein, 205-258. New York: Global Scholarly Publications, 2012. “Just War Claims: Historical Theory, Abu Ghraib, and Modern Rhetoric.” In International Criminal Justice: Legal and Theoretical Perspectives, edited by George Andreopoulos, Rosemary Barberet, and James Levine, 33-67. New York: Springer Press, 2011. “An Essay on Tibetan Poetry.” In Light of Fearless Indestructible Wisdom: The Life and Legacy of His Holiness Dudjom Rinpoche, written by Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal. Prose translation and annotations by Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal and Carl Stuendel. Verse and song translation by Toy-Fung Tung and Marie-Louise Friquegnon, app. -

Entering Into the Conduct of the Bodhisattva)

Dharma Path BCA Ch1.doc Dzogchen Khenpo Choga Rinpocheʹs Oral Explanations of Khenpo Kunpal’s Commentary on Shantidevaʹs Bodhisattvacaryavatara (Entering into the Conduct of the Bodhisattva) Notes: ʺText sectionʺ‐s refer to Khenpo Kunpalʹs commentary on the BCA. ʺBCAʺ refers to the Bodhisattvacaryavatara, by Shantideva. The text sections relating directly to the individual stanzas of the BCA, which are the subject matter of Dharma Path classes, begin on ʺText section 158ʺ below. Dzogchen Khenpo Chogaʹs Oral Explanations, starting with ʺText section 37ʺ below are explanations both of the original BCA text, and also of Khenpo Kunpalʹs own commentary on this text. For more background on these teachings, see also Dzogchen Khenpo Chogaʹs ʺIntroduction to the Dharma Pathʺ available online at the Dzogchen Lineage website at: http://www.dzogchenlineage.org/bca.html#intro These materials are copyright Andreas Kretschmar, and are subject to the terms of the copyright provisions described on his website: http://www.kunpal.com/ ============================================================================== Text section 37: This word‐by‐word commentary on the Bodhisattva‐caryavatara was written by Khenpo Kunzang Palden, also known as Khenpo Kunpal, according to the teachings he received over a six‐month period from his root guru, Dza Paltrul Rinpoche, who is here referred to as the Manjugosha‐like teacher. These precious teachings are titled Drops of Nectar. The phrase personal statement connotes that Khenpo Kunpal received in person the oral instructions, which are themselves definitive statements, directly from Paltrul Rinpoche. 1 Dharma Path BCA Ch1.doc Text sections 38‐44: In his preface Khenpo Kunpal includes his declaration of respect, his pledge to compose the commentary, and a foreword. -

NYINGMA S.No. NAME REGION CURRENT RESIDENCE

NYINGMA S.no. NAME REGION CURRENT CURRENT VOTES RESIDENCE DESIGNATION 1 Khenpo Sonam Tenphel Raykhey Dharamshala Deputy Speaker of 801 Tibetan Parliament 2 Khenpo Pema Choephel Tsawa Bir Abbot of Palyul 457 Choekorling 3 Chamra Temey Degey Delhi Secretary of 113 Gyaltsen Chushigangdrug 4 Tulku Ogyen Topgyal Nangchen Bir Former MP 5 5 Tsering Phuntsok Khojo Bylakuppe Former Kalon 3 6 Dra Kalsang Phadruk Nepal Monk 3 7 Khenpo Ngawang Nangchen Bylakuppe Former Secretary of 2 Dorjee Namdroling monastery 7 Khenpo Jamphel Tenzin Minyak Kollegal Serving Abbot of 2 Dzogchen monastery KAGYU S.no NAME REGION CURRENT CURRENT VOTES RESIDENCE DESIGNATION 1 Kunga Sonam Dege Bodhgaya Administrator of Ter Gar 239 2 Tenpa Yarphel Chamdo Dharamshala Serving MP 224 3 Tenzin Jampa Lingtsang Tashi Jong Editor of Bhutanese 221 Dictionary 4 Sonam Dadhul Nagchu Kumrao Former MP 175 5 Pema Rigzin Gapa Dickyiling Director of Jangchupling 116 6 Karma Choephel Tadhun Dharamshala Serving MP 54 7 Karma Pema Yangpachen Rawangla Professor 15 8 Chemey Rigzin Gapa Dickyiling Principal of Drigkung 3 SAKYA S.no NAME REGION CURRENT CURRENT VOTES RESIDENCE DESIGNATION 1 Lobpon Thupten Markham Puruwala Editor of Sakya 169 Gyaltsen Dictionary 2 Geshe Gaze Tse Ringpo Khojo Chauntra Serving MP 163 3 Khenpo Kadak Ngodup Tehor Gopalpur Religious Teacher 140 Sonam 4 Acharya Lobsang Lhokha Gopalpur Tibetan Language 100 Gyaltsen Teacher 5 Dao Ngawang Lodoe Gapa Kumrao Chairman of Local 8 Assembly 6 Lobsang Gyatso Lhokha Gopalpur TCV Teacher 3 7 Khenpo Norbu Tsering Degey Chauntra Serving MP 3 8 Ngawang Sangpo Purang Mundgod Fromer administrator of 1 Dhamchoeling GELUG S.no. -

Social Manifestations of XIV Shamar Rinpoche Posthumous Activity

International Proceedings of Economics Development and Research IPEDR vol.83 (2015) © (2015) IACSIT Press, Singapore Social manifestations of XIV Shamar Rinpoche posthumous activity Malwina Krajewska Nicolaus Copernicus University, Torun, Poland Abstract. This paper analyze and present social phenomena which appeared after the sudden death of Tibetan Lama- XIV Kunzig Shamar Rinpoche Mipham Chokyi Lodro. It contain ethnographic descriptions and reflections made during anthropological fieldwork in Germany as well in Nepal. It shows how Buddhist teacher can influence his practitioners even after death. What is more this paper provide reliable information about the role of Shamarpa in Kagyu tradition. Keywords: Anthropology, Buddhism, Fieldwork, Cremation. 1. Introduction Information and reflections published in this paper are an attempt to present anthropological approach to current and global situation of one specific tradition within Tibetan Buddhism. The sudden death of Kagyu tradition Lineage Holder- Shamarpa influenced many people from America, Asia, Australia and Europe and Russia. In following section of this article you will find examples of social phenomena connected to this situation, as well basic information about Kagyu tradition. 2. Cremation at Shar Minub Monastery 31 of July 2014 was very hot and sunny day (more than 30 degrees) in Kathmandu, Nepal. Thousands of people gathered at Shar Minub Monastery and in its surroundings. On the rooftop of unfinished (still under construction) main building you could see a crowd of high Tibetan Buddhist Rinpoches and Lamas - representing different Tibetan Buddhist traditions. All of them were simultaneously leading pujas and various rituals. Among them Shamarpa family members as well as other noble guests were also present. -

Tibetan Buddhism, Vajrayana, and the Lineage of Chogyam Trunpa

Tibetan Buddhism, Vajrayana, and the lineage of Chögyam Trungpa, Rinpoche The Vajrayana is the third major yana or vehicle of buddhadharma. It is built on and incorporates the Foundational teachings (Hinayana) and the Mahayana. It is also known as the Secret Mantra. The Vajrayana teachings are secret teachings, passed down through lineages from teacher to student. They were preserved and developed extensively in Tibet over 1200 years. The beginnings of Vajrayana are in India, initially spreading out through areas of Mahayana Buddhism and later the Kushan Empire. By the 12th century most of the Indian subcontinent was overtaken by the Moghul Empire and almost all of Buddhism was suppressed. The majority of Vajrayana texts, teachings and practices were preserved intact in Tibet. Vajrayana is characterized by the use of skillful means (upaya), expediting the path to enlightenment mapped out in the Mahayana teachings. The skillful means are an intensification of meditation practices coupled with an advanced understanding of the view. Whereas the conventional Mahayana teachings view the emptiness of self and all phenomena as the final goal on the path to Buddhahood, Vajrayana starts by acknowledging this goal as already fully present in all sentient beings. The practice of the path is to actualize that in ourselves and all beings through transforming confusion and obstacles, revealing their natural state of primordial wisdom. This is accomplished through sacred outlook (view), and employing meditation techniques such as visualization in deity practice and mantra recitation. One major stream of Vajrayana is known as Mahamudra (Great Seal), which incorporates the techniques noted above in a process of creation (visualization, mantra) and completion (yogas) leading to the Great Seal. -

Spring/Summer 2010 in This Issue

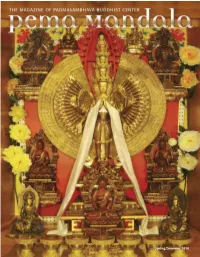

Spring/Summer 2010 In This Issue 1 Letter from the Venerable Khenpo Rinpoches 2 Brilliant Lotus Garland of Glorious Wisdom A Glimpse into the Ancient Lineage of Khenchen Palden Volume 9, Spring/Summer 2010 Sherab Rinpoche A Publication of 6 Entrusted: The Journey of Khenchen Rinpoche’s Begging Bowl Padmasambhava Buddhist Center 9 Fulfillment of Wishes: Nyingma Lineage of Tibetan Buddhism Eight Great Stupas & Five Dhyani Buddhas Founding Directors 12 How I Met the Khenpo Rinpoches Ven. Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche Ven. Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche 14 Schedule of Teachings 16 The Activity Samayas of Anuyoga Ani Lorraine, Co-Editor An Excerpt from the 2009 Shedra, Year 7: Anuyoga Pema Dragpa, Co-Editor Amanda Lewis, Assistant Editor 18 Garland of Views Pema Tsultrim, Coordinator Beth Gongde, Copy Editor 24 The Fruits of Service Michael Ray Nott, Art Director 26 2009 Year in Review Sandy Mueller, Production Editor PBC and Pema Mandala Office For subscriptions or contributions to the magazine, please contact: Padma Samye Ling Attn: Pema Mandala 618 Buddha Highway Sidney Center, NY 13839 (607) 865-8068 [email protected] Pema Mandala welcomes all contributions submitted for consideration. All accepted submissions will be edited appropriately for Cover: 1,000 Armed Chenrezig statue with the publication in a magazine representing the Five Dhyani Buddhas in the Shantarakshita Padmasambhava Buddhist Center. Library at Padma Samye Ling Please email submissions to Photographed by Amanda Lewis [email protected]. © Copyright 2010 by Padmasambhava Buddhist Center International. Material in this publication is copyrighted and may not be reproduced by photocopy or any other means without obtaining written permission from the publisher. -

Studies on Ethnic Groups in China

Kolas&Thowsen, Margins 1/4/05 4:10 PM Page i studies on ethnic groups in china Stevan Harrell, Editor Kolas&Thowsen, Margins 1/4/05 4:10 PM Page ii studies on ethnic groups in china Cultural Encounters on China’s Ethnic Frontiers Edited by Stevan Harrell Guest People: Hakka Identity in China and Abroad Edited by Nicole Constable Familiar Strangers: A History of Muslims in Northwest China Jonathan N. Lipman Lessons in Being Chinese: Minority Education and Ethnic Identity in Southwest China Mette Halskov Hansen Manchus and Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861–1928 Edward J. M. Rhoads Ways of Being Ethnic in Southwest China Stevan Harrell Governing China’s Multiethnic Frontiers Edited by Morris Rossabi On the Margins of Tibet: Cultural Survival on the Sino-Tibetan Frontier Åshild Kolås and Monika P. Thowsen Kolas&Thowsen, Margins 1/4/05 4:10 PM Page iii ON THE MARGINS OF TIBET Cultural Survival on the Sino-Tibetan Frontier Åshild Kolås and Monika P. Thowsen UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS Seattle and London Kolas&Thowsen, Margins 1/7/05 12:47 PM Page iv this publication was supported in part by the donald r. ellegood international publications endowment. Copyright © 2005 by the University of Washington Press Printed in United States of America Designed by Pamela Canell 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 5 4 3 2 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be repro- duced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any infor- mation storage or retrieval system, without permission in writ- ing from the publisher.