Danish Foreign Policy Review 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Success Story Or a Failure? : Representing the European Integration in the Curricula and Textbooks of Five Countries

I Inari Sakki A Success Story or a Failure? Representing the European Integration in the Curricula and Textbooks of Five Countries II Social psychological studies 25 Publisher: Social Psychology, Department of Social Research, University of Helsinki Editorial Board: Klaus Helkama, Chair Inga Jasinskaja-Lahti, Editor Karmela Liebkind Anna-Maija Pirttilä-Backman Kari Mikko Vesala Maaret Wager Jukka Lipponen Copyright: Inari Sakki and Unit of Social Psychology University of Helsinki P.O. Box 4 FIN-00014 University of Helsinki I wish to thank the many publishers who have kindly given the permission to use visual material from their textbooks as illustrations of the analysis. All efforts were made to find the copyright holders, but sometimes without success. Thus, I want to apologise for any omissions. ISBN 978-952-10-6423-4 (Print) ISBN 978-952-10-6424-1 (PDF) ISSN 1457-0475 Cover design: Mari Soini Yliopistopaino, Helsinki, 2010 III ABSTRAKTI Euroopan yhdentymisprosessin edetessä ja syventyessä kasvavat myös vaatimukset sen oikeutuksesta. Tästä osoituksena ovat muun muassa viimeaikaiset mediassa käydyt keskustelut EU:n perustuslakiäänestysten seurauksista, kansalaisten EU:ta ja euroa kohtaan osoittamasta ja tuntemasta epäluottamuksesta ja Turkin EU-jäsenyydestä. Taloudelliset ja poliittiset argumentit tiiviimmän yhteistyön puolesta eivät aina riitä kansalaisten tuen saamiseen ja yhdeksi ratkaisuksi on esitetty yhteisen identiteetin etsimistä. Eurooppalaisen identiteetin sanotaan voivan parhaiten muodostua silloin, kun perheen, koulutuksen -

An Analysis of Conditions for Danish Defence Policy – Strategic Choices

centre for military studies university of copenhagen An Analysis of Conditions for Danish Defence Policy – Strategic Choices 2012 This analysis is part of the research-based services for public authorities carried out at the Centre for Military Studies for the parties to the Danish Defence Agreement. Its purpose is to analyse the conditions for Danish security policy in order to provide an objective background for a concrete discussion of current security and defence policy problems and for the long-term development of security and defence policy. The Centre for Military Studies is a research centre at the Department of —Political Science at the University of Copenhagen. At the centre research is done in the fields of security and defence policy and military strategy, and the research done at the centre forms the foundation for research-based services for public authorities for the Danish Ministry of Defence and the parties to the Danish Defence Agreement. This analysis is based on research-related method and its conclusions can —therefore not be interpreted as an expression of the attitude of the Danish Government, of the Danish Armed Forces or of any other authorities. Please find more information about the centre and its activities at: http://cms.polsci.ku.dk/. References to the literature and other material used in the analysis can be found at http://cms.polsci.ku.dk/. The original version of this analysis was published in Danish in April 2012. This version was translated to English by The project group: Major Esben Salling Larsen, Military Analyst Major Flemming Pradhan-Blach, MA, Military Analyst Professor Mikkel Vedby Rasmussen (Project Leader) Dr Lars Bangert Struwe, Researcher With contributions from: Dr Henrik Ø. -

Defence Budgets and Cooperation in Europe: Developments, Trends and Drivers

January 2016 Defence Budgets and Cooperation in Europe: Developments, Trends and Drivers Edited by Alessandro Marrone, Olivier De France, Daniele Fattibene Defence Budgets and Cooperation in Europe: Developments, Trends and Drivers Edited by Alessandro Marrone, Olivier De France and Daniele Fattibene Contributors: Bengt-Göran Bergstrand, FOI Marie-Louise Chagnaud, SWP Olivier De France, IRIS Thanos Dokos, ELIAMEP Daniele Fattibene, IAI Niklas Granholm, FOI John Louth, RUSI Alessandro Marrone, IAI Jean-Pierre Maulny, IRIS Francesca Monaco, IAI Paola Sartori, IAI Torben Schütz, SWP Marcin Terlikowski, PISM 1 Index Executive summary ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 Introduction ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 List of abbreviations --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 7 Chapter 1 - Defence spending in Europe in 2016 --------------------------------------------------------- 8 1.1 Bucking an old trend ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 8 1.2 Three scenarios ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 10 1.3 National data and analysis ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- 11 1.3.1 Central and Eastern Europe -------------------------------------------------------------------- 11 1.3.2 Nordic region -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Opskriften På Succes Stort Tema Om Det Nye Politiske Landkort

UDGAVE NR. 5 EFTERÅR 2016 Uffe og Anders Opskriften på succes Stort tema om det nye politiske landkort MAGTDUO: Metal-bossen PORTRÆT: Kom tæt på SKIPPER: Enhedslistens & DI-direktøren Dansk Flygtningehjælps revolutionære kontrolfreak topchef www.mercuriurval.dk Ledere i bevægelse Ledelse i balance Offentlig ledelse + 150 85 250 toplederansættelser konsulenter over ledervurderinger og i den offentlige sektor hele landet udviklingsforløb på over de sidste tre år alle niveauer hvert år Kontakt os på [email protected] eller ring til os på 3945 6500 Fordi mennesker betyder alt EFTERÅR 2016 INDHOLD FORDOMME Levebrød, topstyring og superkræfter 8 PORTRÆT Skipper: Enhedslistens nye profil 12 NYBRUD Klassens nye drenge Anders Samuelsen og Uffe Elbæk giver opskriften på at lave et nyt parti. 16 PARTIER Nyt politisk kompas Hvordan ser den politiske skala ud i dag? 22 PORTRÆT CEO for flygningehjælpen A/S Kom tæt på to-meter-manden Andreas Kamm, som har vendt Dansk Flygtningehjælp fra krise til succes. 28 16 CIVILSAMFUND Danskerne vil hellere give gaver end arbejde frivilligt 34 TOPDUO Spydspidserne 52 Metal-bossen Claus Jensen og DI-direktøren Karsten Dybvad udgør et umage, men magtfuldt par. 40 INDERKREDS Topforhandlerne Mød efterårets centrale politikere. 44 INTERVIEW Karsten Lauritzen: Danmark efter Brexit 52 BAGGRUND Den blinde mand og 12 kampen mod kommunerne 58 KLUMME Klumme: Jens Christian Grøndahl 65 3 ∫magasin Efterår 2016 © �∫magasin er udgivet af netavisen Altinget ANSVARSHAVENDE CHEFREDAKTØR Rasmus Nielsen MAGASINREDAKTØR Mads Bang REDAKTION Anders Jerking Erik Holstein Morten Øyen Jensen Klaus Ulrik Mortensen Kasper Frandsen Mads Bang Hjalte Kragesteen Sine Riis Lund Kim Rosenkilde Rikke Albrechtsen Anne Justesen Frederik Tillitz Erik Bjørn Møller Toke Gade Crone Kristiansen Søren Elkrog Friis Emma Qvirin Holst Carsten Terp Rasmus Løppenthin Amalie Bjerre Christensen Tyson W. -

European Defence Cooperation After the Lisbon Treaty

DIIS REPORT 2015: 06 EUROPEAN DEFENCE COOPERATION AFTER THE LISBON TREATY The road is paved for increased momentum This report is written by Christine Nissen and published by DIIS as part of the Defence and Security Studies. Christine Nissen is PhD student at DIIS. DIIS · Danish Institute for International Studies Østbanegade 117, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark Tel: +45 32 69 87 87 E-mail: [email protected] www.diis.dk Layout: Lone Ravnkilde & Viki Rachlitz Printed in Denmark by Eurographic Danmark Coverphoto: EU Naval Media and Public Information Office ISBN 978-87-7605-752-7 (print) ISBN 978-87-7605-753-4 (pdf) © Copenhagen 2015, the author and DIIS Table of Contents Abbreviations 4 Executive summary / Resumé 5 Introduction 7 The European Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) 11 External Action after the Lisbon Treaty 12 Consequences of the Lisbon changes 17 The case of Denmark 27 – consequences of the Danish defence opt-out Danish Security and defence policy – outside the EU framework 27 Consequences of the Danish defence opt-out in a Post-Lisbon context 29 Conclusion 35 Bibliography 39 3 Abbreviations CFSP Common Foreign and Security Policy CPCC Civilian Planning and Conduct Capability CSDP Common Security and Defence Policy DEVCO European Commission – Development & Cooperation ECHO European Commission – Humanitarian Aid & Civil Protection ECJ European Court of Justice EDA European Defence Agency EEAS European External Action Service EMU Economic and Monetary Union EU The European Union EUMS EU Military Staff FAC Foreign Affairs Council HR High -

University of Copenhagen FACULTY of SOCIAL SCIENCES Faculty of Social Sciences UNIVERSITY of COPENHAGEN · DENMARK PHD DISSERTATION 2019 · ISBN 978-87-7209-312-3

Arctic identity interactions Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies Jacobsen, Marc Publication date: 2019 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (APA): Jacobsen, M. (2019). Arctic identity interactions: Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies. Download date: 11. okt.. 2021 DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE university of copenhagen FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES faculty of social sciences UNIVERSITY OF COPENHAGEN · DENMARK PHD DISSERTATION 2019 · ISBN 978-87-7209-312-3 MARC JACOBSEN Arctic identity interactions Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies and Denmark’s Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s identity interactions Arctic Arctic identity interactions Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies PhD Dissertation 2019 Marc Jacobsen DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE university of copenhagen FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES faculty of social sciences UNIVERSITY OF COPENHAGEN · DENMARK PHD DISSERTATION 2019 · ISBN 978-87-7209-312-3 MARC JACOBSEN Arctic identity interactions Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies and Denmark’s Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s identity interactions Arctic Arctic identity interactions Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies PhD Dissertation 2019 Marc Jacobsen Arctic identity interactions Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies Marc Jacobsen PhD Dissertation Department of Political Science University of Copenhagen September 2019 Main supervisor: Professor Ole Wæver, University of Copenhagen. Co-supervisor: Associate Professor Ulrik Pram Gad, Aalborg University. -

Beretning Regeringens Oplysninger Til Folketinget

2008-09 Beretning af almen art: Beretning 10 Offentligt OMTRYK Beretning nr. 10 Folketinget 2008-09 OMTRYK Korrekturændringer i papirversionen Beretning afgivet af Udvalget for Forretningsordenen den 18. september 2009 Beretning om regeringens oplysninger til Folketinget 1. Indledning Sundhedsudvalget nævner i brevet, at sundhedsministeren Baggrunden for denne beretning er udvalgets behandling under et samråd i udvalget den 13. maj 2009 bl.a. oplyste, at af en henvendelse fra Sundhedsudvalget. I et brev fra Sund- udredningsarbejdets hovedkonklusioner allerede er tilgået hedsudvalget af 25. maj 2009 til Folketingets formand ud- formanden for Det Konservative Folkeparti, der i marts trykte et flertal i udvalget (S, SF, RV, EL og Pia Christmas- 2009 brugte udredningsarbejdet som grundlag for en politisk Møller (UFG)) utilfredshed med, at sundhedsministeren til- udmelding i den offentlige debat. bageholdt et ministerielt udredningsarbejde om de såkaldte Folketingets formand bad ved brev af 26. maj 2009 om DRG-takster. (DRG-takster er de takster, der bl.a. bruges til sundhedsministerens eventuelle bemærkninger til udvalgets beregning af det offentliges betaling for patientbehandling brev, og ministeren har i et brev af 10. juni 2009 udtalt sig på private sygehuse under det udvidede frie sygehusvalg). om sagen. Kopi af sundhedsministerens brev er gengivet Et mindretal i udvalget (V, DF og KF) kunne ikke støtte som bilag 2til denne beretning. indholdet af brevet og henviste til, at Sundhedsudvalgets Sundhedsministeren anfører, at han finder det uhensigts- formand på et samråd den 13. maj 2009 konkluderede, at mæssigt at udlevere udredningsarbejdet til udvalget, fordi en udvalget ville få oversendt udredningen om DRG-takster i offentliggørelse vil kunne påvirke forhandlingerne mellem januar 2010. -

Official Journal C 374 Volume 42 of the European Communities 23 December 1999

ISSN 0378–6986 Official Journal C 374 Volume 42 of the European Communities 23 December 1999 English edition Information and Notices Notice No Contents Page I Information ...... II Preparatory Acts Committee of the Regions Session of September 1999 1999/C 374/01 Opinion of the Committee of the Regions on the ‘Communication from the Commission on A northern dimension for the policies of the Union’ . 1 1999/C 374/02 Opinion of the Committee of the Regions on the ‘Amended proposal for Council Directive on assessment of the effects of certain plans and programmes on the environment’ . 9 1999/C 374/03 Opinion of the Committee of the Regions on the ‘Proposal for a Council Regulation (EC) amending Council Regulation (EEC) No 1210/90 of 7 May 1990 on the establishment of the European Environment Agency and the European Information and Observation Network’ . 10 1999/C 374/04 Opinion of the Committee of the Regions on the ‘Commission report to the European Council “Better lawmaking 1998 — a shared responsibility”’ . 11 1999/C 374/05 Opinion of the Committee of the Regions on the ‘Institutional Aspects of Enlargement “Local and Regional Government at the heart of Europe”’ . 15 1999/C 374/06 Opinion of the Committee of the Regions on the ‘Implementation of EU law by the regions and local authorities’. 25 Price: 19,50 EUR EN (Continued overleaf) Notice No Contents (Continued) Page 1999/C 374/07 Opinion of the Committee of the Regions on ‘the Proposal for a European Parliament and Council decision amending Decision No. 1254/96/EC laying down a series of guidelines for trans-European energy networks’ . -

EUI RSCAS Working Paper 2020

RSCAS 2020/88 Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Integrating Diversity in the European Union (InDivEU) The Politics of Differentiated Integration: What do Governments Want? Country Report - Denmark Viktor Emil Sand Madsen European University Institute Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Integrating Diversity in the European Union (InDivEU) The Politics of Differentiated Integration: What do Governments Want? Country Report - Denmark Viktor Emil Sand Madsen EUI Working Paper RSCAS 2020/88 Terms of access and reuse for this work are governed by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC- BY 4.0) International license. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the working paper series and number, the year and the publisher. ISSN 1028-3625 © Viktor Emil Sand Madsen, 2020 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC-BY 4.0) International license. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Published in December 2020 by the European University Institute. Badia Fiesolana, via dei Roccettini 9 I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual author(s) and not those of the European University Institute. This publication is available in Open Access in Cadmus, the EUI Research Repository: https://cadmus.eui.eu Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies The Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, created in 1992 and currently directed by Professor Brigid Laffan, aims to develop inter-disciplinary and comparative research on the major issues facing the process of European integration, European societies and Europe’s place in 21st century global politics. -

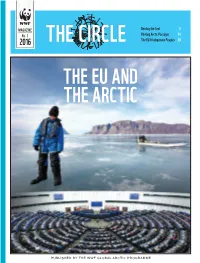

The Eu and the Arctic

MAGAZINE Dealing the Seal 8 No. 1 Piloting Arctic Passages 14 2016 THE CIRCLE The EU & Indigenous Peoples 20 THE EU AND THE ARCTIC PUBLISHED BY THE WWF GLOBAL ARCTIC PROGRAMME TheCircle0116.indd 1 25.02.2016 10.53 THE CIRCLE 1.2016 THE EU AND THE ARCTIC Contents EDITORIAL Leaving a legacy 3 IN BRIEF 4 ALYSON BAILES What does the EU want, what can it offer? 6 DIANA WALLIS Dealing the seal 8 ROBIN TEVERSON ‘High time’ EU gets observer status: UK 10 ADAM STEPIEN A call for a two-tier EU policy 12 MARIA DELIGIANNI Piloting the Arctic Passages 14 TIMO KOIVUROVA Finland: wearing two hats 16 Greenland – walking the middle path 18 FERNANDO GARCES DE LOS FAYOS The European Parliament & EU Arctic policy 19 CHRISTINA HENRIKSEN The EU and Arctic Indigenous peoples 20 NICOLE BIEBOW A driving force: The EU & polar research 22 THE PICTURE 24 The Circle is published quar- Publisher: Editor in Chief: Clive Tesar, COVER: terly by the WWF Global Arctic WWF Global Arctic Programme [email protected] (Top:) Local on sea ice in Uumman- Programme. Reproduction and 8th floor, 275 Slater St., Ottawa, naq, Greenland. quotation with appropriate credit ON, Canada K1P 5H9. Managing Editor: Becky Rynor, Photo: Lawrence Hislop, www.grida.no are encouraged. Articles by non- Tel: +1 613-232-8706 [email protected] (Bottom:) European Parliament, affiliated sources do not neces- Fax: +1 613-232-4181 Strasbourg, France. sarily reflect the views or policies Design and production: Photo: Diliff, Wikimedia Commonss of WWF. Send change of address Internet: www.panda.org/arctic Film & Form/Ketill Berger, and subscription queries to the [email protected] ABOVE: Sarek glacier, Sarek National address on the right. -

The Danish EU Presidency 2012 a Midterm Report Adler-Nissen, Rebecca; Hassing Nielsen, Julie; Sørensen, Catharina

The Danish EU Presidency 2012 A Midterm Report Adler-Nissen, Rebecca; Hassing Nielsen, Julie; Sørensen, Catharina Publication date: 2012 Document version Early version, also known as pre-print Citation for published version (APA): Adler-Nissen, R., Hassing Nielsen, J., & Sørensen, C. (2012). The Danish EU Presidency 2012: A Midterm Report. Swedish Institute for European Policy Studies, SIEPS. Download date: 27. Sep. 2021 ´ 2012:1op Rebecca Adler-Nissen, Julie Hassing Nielsen and Catharina Sørensen The Danish EU Presidency 2012: A Midterm Report Rebecca Adler-Nissen, Julie Hassing Nielsen and Catharina Sørensen The Danish EU Presidency 2012: A Midterm Report - SIEPS – 2012:1op SIEPS 2012:1op May 2012 Published by the Swedish Institute for European Policy Studies The report is available at www.sieps.se The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors Cover: Svensk Information AB Print: EO Grafiska AB Stockholm, May 2012 ISSN 1651-8071 ISBN 91-85129-86-0 Preface The Swedish Institute for European Policy Studies bi-annually publishes a report on the incumbent presidency of the EU focusing on the agenda, domestic factors and the country’s specific relation to the European integration process. The role of the rotating presidency of the council has gone through a considerable change since the entry into force of the Lisbon treaty. The European Council is now chaired by a permanent President and foreign affairs are placed under the chairmanship of the High Representative. Furthermore, the presidencies are more systematically coordinated within a Trio of presidencies. These changes limit the role of the presidency, but there are still many tasks that remain in the hands of the country holding the presidency. -

The Legacy of Neutrality in Finnish and Swedish Security Policies in Light of European Integration

Traditions, Identity and Security: the Legacy of Neutrality in Finnish and Swedish Security Policies in Light of European Integration. Johan Eliasson PhD Candidate/Instructor Dep. Political Science 100 Eggers Hall Maxwell school of Citizenship and Public Affairs Syracuse University Syracuse, NY 13244-1090 Traditions, Identity and Security 2 . Abstract The militarily non-allied members of the European Union, Austria, Finland, Ireland and Sweden, have undergone rapid changes in security policies since 1999. Looking at two states, Finland and Sweden, this paper traces states’ contemporary responses to the rapid development of the European Security and Defense Policy (ESDP) to their historical experiences with different types of neutrality. It is argued that by looking at the legacies of different types of neutrality on identity and domestic rules, traditions, norms, and values, we can better explain how change occurred, and why states have pursued slightly different paths. This enhances our understanding broadly of the role of domestic institutions in accounting for policy variation in multilateral regional integration, and particularly in the EU. In the process, this study also addresses a question recently raised by other scholars: the role of neutrality in Europe. Traditions, Identity and Security 3 . 1. Introduction The core difference between members and non-members of a defense alliance lie in obligations to militarily aid a fellow member if attacked, and, to this end, share military strategy and related information. The recent and rapid institutionalization of EU security and defense policy is blurring this distinction beyond the increased cooperation and solidarity emanating from geopolitical changes, NATO’s expansion and new-found role in crisis management, or, later, the 9/11 attacks.