Copyright by Darrin Mark Hanson 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guest Speakers to Explore Augustana's Legacy at Gathering VIII in St. Peter, June 21–24, 2012

TheAugustana Heritage Newsletter Volume 7 Number 3 Fall 2011 Guest speakers to explore Augustana’s legacy at Gathering VIII in St. Peter, June 21–24, 2012 Guest speakers will explore The plenary speakers include: Bishop Antje Jackelén the theme, “A Living of the Diocese of Lund, Church of Sweden, on “The Legacy,” at Gathering VIII Church in Two Secular Cultures: Sweden and America”; of the Augustana Heritage Dr. James Bratt, Professor of Church History at Calvin Association at Gustavus College, Grand Rapids, Michigan, on “Augustana in Adolphus College in St. American Church History”; The Rev. Rafael Malpica Peter, Minnesota, from Padil, executive director of the Global Mission Unit, June 21-24, 2012. Even Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, on “Global though 2012 will mark Missions Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow”. the 50th anniversary of “Augustana: A Theological Tradition” will be the the Augustana Lutheran theme of a panel discussion led by the Rev. Dr. Harold Church’s merger with Skillrud, the Rev. Dr. Dale Skogman and the Rev. Dr. other Lutheran churches Theodore N. Swanson. The Rev. Dr. Arland J. Hultgren after 102 years since its will moderate the discussion. founding by Swedish The Jenny Lind Singer for 2012, a young musician immigrants in 1860, it from Sweden, will give a concert on Saturday evening, continues as a “living June 23. See Page 14 for the tentative schedule for each Bishop Antje Jackelén of legacy” among Lutherans day in what promises to be another wonderful AHA the Church of Sweden today. Gathering. Garrison Keillor, known internationally for the Minnesota Public Radio show “A Prairie Home Companion,” will speak on “Life among the Lutherans,” at the opening session on Thursday, June 21. -

A Common Word Between Us Andyou

A COMMON WORD BETWEEN US ANDYOU the royal aal al-bayt institute for islamic thought 2009 • Jordan A COMMON WORD BETWEEN US ANDYOU the royal aal al-bayt institute for islamic thought january 2009 • Jordan © , The Royal Aal al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought, Jordan CONTENTS “A Common Word”: Accomplishments ‒ v • A Common Word Between Us and You . Summary and Abridgement . Full Text of A Common Word List of Signatories • Responses by: • Professor David Ford ( . ) • Tony Blair ( . ) • “TheYale Response” ( . ) • WorldAlliance of Reformed Churches ( . ) • The Mennonite Church ( . ) • The World Council of Churches ( .. ) • Archbishop Petrosyan on behalf of Karekin II, Supreme Patriarch of allArmenians (.. ) • PatriarchAlexy II of Moscow ( .. ) • TheArchbishop of Canterbury ( .. ) • TheArchbishop of Cyprus ( . ) • The Baptist WorldAlliance ( . ) • The Council of Bishops of The United Methodist Church ( .. ) • The Lutheran World Federation ( .. ) • . Yale Conference, USA • Final Statement . Cambridge Conference, UK • Final Communiqué . Rome Conference, Italy • Address by Pope Benedict XVI • Address by Seyyed Hossein Nasr • Speech by Sheikh Mustafa Ceric • Final Declaration . Eugen Biser Prize Ceremony, Germany • Award Ceremony Speech by H.R.H. Prince Ghazi bin Muhammad • Frequently Asked Questions INTRODUCTION “A COMMON WORD”: ACCOMPLISHMENTS 2007 –2008 In the Name of God Over the last year since its launch the A Common Word initiative ( see www.acommonword.com) has become the world’s leading interfaith dialogue initiative between Christians and Muslims specifically, and has achieved historically unprecedented global acceptance and “trac - tion” as an interfaith theological document. A Common Word was launched on October th as an open letter signed by leading Muslim scholars and intellectuals (including such figures as the Grand Muftis of Egypt, Syria, Jordan, Oman, Bosnia, Russia, Chad and Istanbul) to the leaders of the Christian Chur- ches and denominations all over the world, including H.H. -

Evangelical Lutheran Church in America God’S Work

SOUTH DAKOTA SYNOD ASSEMBLY June 10-11, 2011 PRELIMINARY REPORT “Walking Wet Together” Augustana College 2001 S Summit Ave Sioux Falls, South Dakota 57197-0001 www.sdsynod.org 1 Table of Contents PART I – Bishop and Staff Reports Report of Presiding Bishop Mark Hanson ................................................................................................ 4-5 Proposed Assembly Agenda ................................................................................................................... 6-7 Synod Assembly Committee and Contributors ......................................................................................... 8 Synod Directory Synod staff ..................................................................................................................................... 9 Executive Committee ..................................................................................................................... 9 Synod Council, Advisors & Audit Committee .......................................................................... 10-11 South Dakota Representatives on Region III & Churchwide Boards ............................................ 11 Committees: Support to Ministries, Candidacy, Consultation, and Discipline ....................... 12-14 Report of Bishop David B. Zellmer ...................................................................................................... 15-16 Anniversaries, Dedications, Roster Changes (Retirements, Necrology, Resignations, Removal, Ordinations, Transfers, Installations) -

The Transfiguration of Our Lord Jesus Took with Him Peter and James and His Brother John and Led Them up a High Mountain, by Themselves

Volume 83, No. 3 - March 2, 2014 The Transfiguration of Our Lord Jesus took with him Peter and James and his brother John and led them up a high mountain, by themselves. And he was transfigured before them, and his face shone like the sun, and his clothes became dazzling white. ...Suddenly a bright cloud overshadowed them, and from the cloud a voice said, “This is my Son, the Beloved; with him I am well pleased; listen to him!” Matthew 17:1-2, 5 Page 2 Former Presiding Bishop Rev. Mark Hanson is our guest speaker at St. Matthew’s Day of Grace, Sunday, March 30 On Sunday, March 30, members of St. Matthew’s and the Greater Milwaukee Synod will welcome The Rev. Mark Hanson, former presiding Bishop of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, as the Day of Grace speaker. He will preach at the morning worship services, and speak during the adult education hour and at an afternoon presentation. As its third presiding Bishop, Rev. Hanson represented the 10,000 congregations of the ELCA to other religious and civil leaders throughout the world during his twelve years in office. He guided the church through difficult times and offered a vision of hope. At the October, 2013 National Assembly of the ELCA, he said, “Yes, we can trust the Holy Spirit, who is at work through this church as we are deeply rooted in Christ and always being made new.” A champion of ecumenical relationships and justice, especially for those most vulnerable, Rev. Hanson has earned wide respect among the world’s religious leaders. -

Inviting You to Worship As Times Expand

publication of Trinity Lutheran Church •Evangelical Lutheran Church in America • trinity-ec.org • 2013, September–Vol. LIX No. 9 Inviting You To Worship Trinity Hosts Bishop As Times Expand Installation Start the fall off right with regular worship. Join us on Wednesdays when The installation of the new NW Synod you’re away on Sunday. Here are the worship options: of Wisconsin ELCA Bishop, Rev. Rick Hoyme, is set for Sunday, September 8, Sundays beginning at 3:00 P.M. in the Worship 8:15 A.M. Worship God in a more traditional style with the beloved hymns, Center. A capacity crowd is anticipated, liturgy, and leadership of the pipe organ and Trinity Choir. Join the Lord’s so plan to arrive early! Supper the first and third Sundays of the month. Bishop Hoyme was elected at the Synod Assembly at UWEC in June and 9:45 A.M. Worship God in a more relaxed style with music by current began serving on July 1. He previously composers led by Harmony In Spirit. Join the Lord’s Supper the first and third served as pastor of Central Lutheran Sundays of the month. Church in Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin. Beginning September 15 10:30 A.M. Worship God in the Chapel (located between the office and First Female preschool). This service is designed to be simple and for parents who choose Bishop of the to have their kids in Sunday School at the same time they worship or for anyone who desires a later worship time. Join in the Lord’s Supper each Sunday. -

Fall 2009 Vol

905237_Augsburg Fall 09:Layout 1 11/10/09 9:52 AM Page 2 AUGSBURG NOW FALL 2009 VOL. 72, NO. 1 making The Magazine of Augsburg College English 111 Bishop Mark Hanson Annual report Velkommen Jul sweets Homecoming 2009 Professor Lisa Jack possible inside Augsburg Now 905237_Augsburg Fall 09:Layout 1 11/10/09 9:52 AM Page 3 Editor Betsey Norgard [email protected] Creative Director Kathy Rumpza ’05 MAL [email protected] Creative Associate-Editorial Wendi Wheeler ’06 notes [email protected] from President Pribbenow Creative Associate-Design Jen Nagorski ’08 On Augsburg’s saga of access and excellence [email protected] Photographer Stephen Geffre [email protected] few years ago my good friend and predeces- founders who believed that education should be for Webmaster/Now Online sor as Augsburg’s president, Bill Frame, all, no matter their circumstances, and that the Bryan Barnes introduced me to Burton Clark’s work on the quality of that education should be of the highest [email protected] aconcept of saga as it relates to the distinc- order because that is what God expects of those Director of News and tive character and identity of colleges and universi- faithful servants who have been given the gift to Media Services ties. A saga, according to Clark, is more than a teach. This is our distinctive gift for the world, an Jeff Shelman story—all of us have stories. A saga is more of a educational experience like no other available to [email protected] mythology—a sense of history and purpose and those who might otherwise not have the opportunity. -

Auxiliary Reports

AUXILIARY REPORTS Lutheran Youth Organization Submitted by Dmitri Krieger, CSIS LYO President Greetings on behalf of the C/SIS Lutheran Youth Organization (LYO). The LYO Board and Planning Committee have been very busy and actively planning for and participating in synod youth events in 2011-2012. Jr. and Sr. High youth from all C/SIS congregations are invited to participate in the two C/SIS LYO events: at Rend Lake Resort in February, and Lake Williamson Retreat Center near Carlinville in November. Our annual gathering at Carlinville was November 18-20, 2011; music was led by Dakota Road and keynoting by Pastor Sue Beadle. We engaged the theme “King Me” (Matthew 25) and learned to treat others as we would Jesus. In July 2011 many of the youth (8th Grade and up) from our synod attended Leadership Lab at Augustana College in Rock Island, IL. Leadership Lab is a ministry of the three Illinois synods that develops youth and young adult leadership and faith growth in the church. The theme at this event was “God’s Top Ten,” based on the Ten Commandments and the Great Commandment. The C/SIS LYO Board and Planning Committee held two planning retreats. One of the planning retreats is in January (2011 and 2012) at Atonement Lutheran Church in Springfield, and the other in August is near Ava (also 2011 and 2012). Board members are elected as three officers and six C/SIS Conference Representatives (plus four at-large positions) to two-year terms at the Carlinville youth gathering. Planning Committee applications are voted upon by the Board members, with five Planning Committee members from each of the six C/SIS Conferences eligible to serve at a time. -

On the Way: Encountering Christ Together

JOINT THEOLOGICAL DAY On the Way: Encountering Christ Together In commemoration of the 500th anniversary of the Reformation, you are invited to come to the table to learn from one another. The Rev. Mark S. Hanson This dialogue on Christian unity is occasioned by the joint publication, “Declaration on the Way: Church, Ministry, and Eucharist.” The Rev. John W. Crossin Thursday, April 20, 2017 — 10:00 am - 4:00 pm Trinity Lutheran Church 210 7th St S — Moorhead, MN 56560 Register online at www.nwmnsynod.org/OnTheWay | Cost: $40 includes lunch Register by April 13, 2017 Free Public Evening Event CAN LUTHERANS AND CATHOLICS BE FRIENDS? Trinity Lutheran Church — 7:00 pm Eastern North Dakota Synod Northwestern Minnesota Synod GET TO KNOW OUR SPEAKERS: Father John W. Crossin Father John Crossin is a priest of the Oblates of St. Francis De Sales. He served as executive director of the Secretariat for Ecumenical and Interreligious Affairs for the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops from December 2011 to December of 2016. Father Crossin continues to serve as a Consultor to the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity and as a member of the Joint Working Group between the Pontifical Council and the World Council of Churches. He was ordained in 1976 and holds a Ph.D. in moral theology, masters’ degrees in psychology and theology from The Catholic University of America. He is past president of the North American Academy of Ecumenists. He has taught at several theological schools including Catholic University, Wesley Theological Seminary, Gettysburg Lutheran Theological Seminary and De Sales School of Theology. -

C:\LS6\Lutherans Say Final.Wpd

Lutherans Say. No. 6 The Religious Beliefs and Practices of Lutheran Lay Leaders in the ELCA Kenneth W. Inskeep Research and Evaluation Evangelical Lutheran Church in America February 3, 2009 For a summary of the results, see page 30. Background of the Survey Lutherans Say. No. 6 (LS6) was first mailed in June, 2008, to a sample of 1,563 people from the mailing list of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America’s (ELCA) Seeds for the Parish. Seeds for the Parish is a congregational resource newspaper produced by the ELCA’s churchwide office and is mailed six times a year to congregational leaders.1 The initial mailing was followed by a postcard reminder and then, several weeks later, those who had not responded received a second copy of the questionnaire. By October 31, 841 people had completed usable questionnaires for a response rate of 54 percent. The primary purpose of LS6 was to gather data that will provide Research and Evaluation with baselines by which the work of the ELCA’s churchwide organization can be evaluated. The churchwide organization has set two priorities within its plan for mission.2 The first priority is “to work collaboratively with congregations, synods, agencies and institutions and other partners, to accompany congregations as growing centers for evangelical mission.” In support of this priority, the churchwide unit Evangelical Outreach and Congregational Mission will give considerable attention to the collective faith practices of discipleship in congregations over the next few years. To set a baseline for evaluating this work, LS6 included a series of questions on the current faith practices of leaders. -

Negotiating Legitimate and Conflicting Values Mark Hanson

Intersections Volume 2016 Article 9 Number 44 Full Issue, Number 44, Fall 2016 2016 Negotiating Legitimate and Conflicting Values Mark Hanson Eboo Patel Katie Baxter Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/intersections Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the Religion Commons Augustana Digital Commons Citation Hanson, Mark; Patel, Eboo; and Baxter, Katie (2016) "Negotiating Legitimate and Conflicting Values," Intersections: Vol. 2016: No. 44, Article 9. Available at: http://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/intersections/vol2016/iss44/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Augustana Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Intersections by an authorized administrator of Augustana Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Negotiating Legitimate and Conflicting Values: A Conversation with Mark Hanson and Eboo Patel, Moderated by Katie Baxter Katie Baxter bishop emeritus of the I’m an alumna of a Lutheran Evangelical Lutheran college. I graduated from Church in America; Wittenberg about 15 years he now serves on the ago and being at Augsburg faculty here at Augsburg College the last couple College. of days has given me the As two people who opportunity to reflect on think a lot about inter- my Lutheran education and faith cooperation in how it has brought me to multiple safe spaces, the place I am now. I use and about public inter- the liberal arts education faith engagement, what I received at Wittenberg are you seeing out there? every day in my work with What situations, settings, Interfaith Youth Core. and scenarios would you And so, I’m thankful for my Lutheran education. -

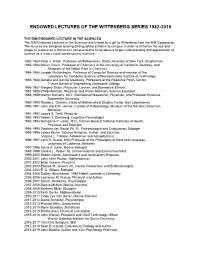

Endowed Lectures of the Wittenberg Series 1982-2019

ENDOWED LECTURES OF THE WITTENBERG SERIES 1982-2019 THE IBM ENDOWED LECTURE IN THE SCIENCES The IBM Endowed Lectures in the Sciences are funded by a gift to Wittenberg from the IBM Corporation. The lectures are designed to bring distinguished scholars to campus in order to enhance the role and image of science on a liberal arts campus and to bring about a larger understanding and appreciation of science as a most crucial contemporary exercise. 1982-1983 Peter J. Hilton, Professor of Mathematics, State University of New York, Binghamton 1983-1984 Melvin Calvin, Professor of Chemistry at the University of California, Berkeley, and Recipient of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1984-1985 Joseph Weizenbaum, Professor of Computer Science and member of the Laboratory for Computer Science at Massachusetts Institute of Technology 1985-1986 Donella and Dennis Meadows, Professors at the Resource Policy Center, Thayer School of Engineering, Dartmouth College 1986-1987 Margery Shaw, Physician, Lawyer, and Biomedical Ethicist 1987-1988 Philip Morrison, Physicist, and Phylis Morrison, Science Educator 1988-1989 Maclyn McCarty, M.D., Biomedical Researcher, Physician, and Professor Emeritus, Rockefeller University 1989-1990 Ronald L. Graham, Head of Mathematical Studies Center, Bell Laboratories 1990-1991 John (Jack) R. Horner, Curator of Paleontology, Museum of the Rockies, Bozeman, Montana 1991-1992 James S. Trefil, Physicist 1992-1993 Robert J. Sternberg, Cognitive Psychologist 1993-1994 Bernadine P. Healy, M.D., Former Head of National Institutes of Health, Physician and Educator 1994-1995 Stephen Jay Gould, Ph. D., Paleontologist and Evolutionary Biologist 1995-1996 James Burke, Science Historian, Author, and Educator Virginia L. -

Reports and Records: Assembly Minutes

Evangelical Lutheran Church in America 2005 Churchwide Assembly Reports and Records: Assembly Minutes August 8–14, 2005 Orlando, Florida Published by the Office of the Secretary Evangelical Lutheran Church in America 8765 West Higgins Road Chicago, Ill. 60631 The Rev. Lowell G. Almen Secretary Copyright © 2006 Evangelical Lutheran Church in America Printed on recycled paper (10% post-consumer waste) Contents Introduction ........................................................... 5 Minutes of the 2005 Churchwide Assembly Plenary Session One................................................ 10 Plenary Session Two................................................ 70 Plenary Session Three............................................... 84 Plenary Session Four............................................... 109 Plenary Session Five............................................... 129 Plenary Session Six................................................ 207 Plenary Session Seven..............................................230 Plenary Session Eight.............................................. 268 Plenary Session Nine............................................... 292 Plenary Session Ten ............................................... 342 Plenary Session Eleven............................................. 360 Plenary Session Twelve ............................................ 413 Supporting Exhibits of the Churchwide Assembly Exhibit A: Members of the Churchwide Assembly Voting Members .............................................. 551 Advisory Members............................................