The Minimally Invasive Operations That Transformed Surgery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Utility of the Digital Rectal Examination in the Emergency Department: a Review

The Journal of Emergency Medicine, Vol. 43, No. 6, pp. 1196–1204, 2012 Published by Elsevier Inc. Printed in the USA 0736-4679/$ - see front matter http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.06.015 Clinical Reviews UTILITY OF THE DIGITAL RECTAL EXAMINATION IN THE EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT: A REVIEW Chad Kessler, MD, MHPE*† and Stephen J. Bauer, MD† *Department of Emergency Medicine, Jesse Brown VA Medical Center and †University of Illinois-Chicago College of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois Reprint Address: Chad Kessler, MD, MHPE, Department of Emergency Medicine, Jesse Brown Veterans Hospital, 820 S Damen Ave., M/C 111, Chicago, IL 60612 , Abstract—Background: The digital rectal examination abdominal pain and acute appendicitis. Stool obtained by (DRE) has been reflexively performed to evaluate common DRE doesn’t seem to increase the false-positive rate of chief complaints in the Emergency Department without FOBTs, and the DRE correlated moderately well with anal knowing its true utility in diagnosis. Objective: Medical lit- manometric measurements in determining anal sphincter erature databases were searched for the most relevant arti- tone. Published by Elsevier Inc. cles pertaining to: the utility of the DRE in evaluating abdominal pain and acute appendicitis, the false-positive , Keywords—digital rectal; utility; review; Emergency rate of fecal occult blood tests (FOBT) from stool obtained Department; evidence-based medicine by DRE or spontaneous passage, and the correlation be- tween DRE and anal manometry in determining anal tone. Discussion: Sixteen articles met our inclusion criteria; there INTRODUCTION were two for abdominal pain, five for appendicitis, six for anal tone, and three for fecal occult blood. -

The Differences Between ICD-9 and ICD-10

Preparing for the ICD-10 Code Set: Fact Sheet 2 October 1, 2015 Compliance Date Get the Facts to be Compliant Alert: The new ICD-10 compliance date is October 1, 2015. The Differences Between ICD-9 and ICD-10 This is the second fact sheet in a series and is focused on the differences between the ICD-9 and ICD-10 code sets. Collectively, the fact sheets will provide information, guidance, and checklists to assist you with understanding what you need to do to implement the ICD-10 code set. The ICD-10 code sets are not a simple update of the ICD-9 code set. The ICD-10 code sets have fundamental changes in structure and concepts that make them very different from ICD-9. Because of these differences, it is important to develop a preliminary understanding of the changes from ICD-9 to ICD-10. This basic understanding of the differences will then identify more detailed training that will be needed to appropriately use the ICD-10 code sets. In addition, seeing the differences between the code sets will raise awareness of the complexities of converting to the ICD-10 codes. Overall Comparisons of ICD-9 to ICD-10 Issues today with the ICD-9 diagnosis and procedure code sets are addressed in ICD-10. One concern today with ICD-9 is the lack of specificity of the information conveyed in the codes. For example, if a patient is seen for treatment of a burn on the right arm, the ICD-9 diagnosis code does not distinguish that the burn is on the right arm. -

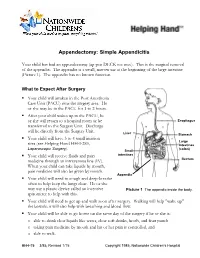

Appendectomy: Simple Appendicitis

Appendectomy: Simple Appendicitis Your child has had an appendectomy (ap pen DECK toe mee). This is the surgical removal of the appendix. The appendix is a small, narrow sac at the beginning of the large intestine (Picture 1). The appendix has no known function. What to Expect After Surgery . Your child will awaken in the Post Anesthesia Care Unit (PACU) near the surgery area. He or she may be in the PACU for 1 to 2 hours. After your child wakes up in the PACU, he or she will return to a hospital room or be Esophagus transferred to the Surgery Unit. Discharge will be directly from the Surgery Unit. Liver Stomach . Your child will have 3 to 4 small incision Large sites (see Helping Hand HH-I-283, Intestines Laparoscopic Surgery (colon) ). Small . Your child will receive fluids and pain intestines medicine through an intravenous line (IV). Rectum When your child can take liquids by mouth, pain medicine will also be given by mouth. Appendix . Your child will need to cough and deep-breathe often to help keep the lungs clear. He or she may use a plastic device called an incentive Picture 1 The appendix inside the body. spirometer to help with this. Your child will need to get up and walk soon after surgery. Walking will help "wake up" the bowels; it will also help with breathing and blood flow. Your child will be able to go home on the same day of the surgery if he or she is: o able to drink clear liquids like water, clear soft drinks, broth, and fruit punch o taking pain medicine by mouth and his or her pain is controlled, and o able to walk. -

Diagnostic Direct Laryngoscopy, Bronchoscopy & Esophagoscopy

Post-Operative Instruction Sheet Diagnostic Direct Laryngoscopy, Bronchoscopy & Esophagoscopy Direct Laryngoscopy: Examination of the voice box or larynx (pronounced “lair-inks”) under general anesthesia. An instrument called a laryngoscope is carefully placed into the mouth and used to visualize the larynx and surrounding structures. Bronchoscopy: Examination of the windpipe below the voice box in the neck and chest under general anesthesia. A long narrow telescope is passed through the larynx and used to carefully inspect the structures of the trachea and bronchi. Esophagoscopy: Examination of the swallowing pipe in the neck and chest under general anesthesia. An instrument called an esophagoscope is passed into the esophagus (just behind the larynx and trachea) and used to visualize the mucus membranes and surrounding structures of the esophagus. Frequently a small biopsy is taken to evaluate for signs of esophageal inflammation (esophagitis). What to Expect: Diagnostic airway endoscopy procedures generally take about 45 minutes to complete. Usually the procedure is well-tolerated and the child is back-to-normal the next day. Mild throat or tongue discomfort may persist for a few days after the procedure and is usually well-controlled with over-the-counter acetaminophen (Tylenol) or ibuprofen (Motrin). Warning Signs: Contact the office immediately at (603) 650-4399 if any of the following develop: • Worsening harsh, high-pitched noisy-breathing (stridor) • Labored breathing with chest retractions or flaring of the nostrils • Bluish discoloration of the lips or fingernails (cyanosis) • Persistent fever above 102°F that does not respond to Tylenol or Motrin • Excessive coughing or respiratory distress during feeding • Coughing or throwing up bright red blood • Excessive drowsiness or unresponsiveness Diet: Resume baseline diet (no special postoperative diet restrictions). -

Chapter 1 History of Laparoscopic Surgery

Chapter 1 History of Laparoscopic Surgery Kiyokazu Nakajima, Jeffrey W. Milsom, and Bartholomäus Böhm Although laparoscopic surgery has transformed surgery only in the past two decades, its evolution is only the natural byproduct of the medical doctor’s curiosity to directly visualize and treat surgical dis- eases. The earliest known attempts to look inside the living human body date from 460 to 375 BC, from the Kos school of medicine led by Hippocrates in Greece.1,2 They described a rectal examination using a speculum remarkably similar to the instruments we use today. Similar specula were discovered in the ruins of Pompeii (70 AD) that were used to examine the vagina, the cervix, and the rectum, and obtain an inside view of the nose and ear.1 The Babylonian Talmud written in 500 AD described a lead siphon, named “Siphophert,” with a mouthpiece, which was bent inward and held a mechul (wooden drain).1,3 The apparatus was introduced into the vagina and was used to differentiate between vaginal and uterine bleeding. During these early years ambient light was used. The term “endoscopein” is attributed to Avicenna (Ibn Sina, 980–1037 AD) of Persia, although an Arabian physician, Albulassim (912–1013 AD), who placed a mirror in front of the exposed vagina, was the fi rst to use refl ected light as a source of illumination for an endoscopic examination. Giulio Caesare Aranzi in Venice (1530–1589) developed the fi rst endoscopic light in 1587. He used the Benedictine monk Don Panuce’s principle of the “camera obscura” for medical purposes – the -

Laryngeal Endoscopy (Rigid, Flexible, and Stroboscopy)

Laryngeal Endoscopy (Rigid, Flexible, and Stroboscopy) Visualization of the larynx can be performed via several different methods. Special tools are required for laryngeal evaluation. Mirror laryngoscopy (1) o While the patient’s tongue is protruded, a mirror is placed in the posterior oropharynx with gentle pressure on the soft palate while light is reflected caudally into the larynx. o Mirror laryngoscopy can be challenging for both the examiner and the patient, has limited magnification, and may require topical anesthesia. o Mirror laryngoscopy provides the most accurate color representation of laryngeal and pharyngeal tissue because there is no light or digital distortion. Flexible laryngoscopy (2) o A flexible laryngoscope is placed into the nasal cavity, through the naso- and oropharynx and positioned cephalad to the larynx for a full laryngeal assessment. o Nasal anesthesia (lidocaine) and/or nasal decongestants (oxymetazoline/phenylephrine) may be applied to the nose for the purpose of improving patient comfort and tolerance o Supplemental procedures such as dynamic voice assessment (comprehensive laryngeal movement evaluation), functional endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (+/- sensory testing), and other laryngeal procedures (ex. injections, laser surgery, biopsies) can be performed during flexible laryngoscopy. o Flexible laryngoscopy is ideal for evaluating vocal fold weakness, real-time/unencumbered evaluation of task-specific abnormalities (ex. my voice is problematic when I do this), and assessing the intensity of glottal attack. Rigid Laryngoscopy (3) o Rigid laryngoscopy is performed by placing a rigid 70- or 90-degree telescope into the oropharynx during tongue protrusion. o Sometimes, oropharyngeal and/or tongue application of anesthesia (ex. lidocaine, cetacaine) can be helpful for patient tolerance. -

Hybrid Procedure Offers a Less Invasive Alternative to Colectomy

The better way to get better Hybrid procedure offers a less invasive alternative to colectomy Insufflation gas provides important advantage The colonoscopy-laparoscopy procedure is made possible through the combined skills of the gastroenterologist and laparoscopic surgeon, and the use of CO2 rather than ambient air for insufflation — the introduction of gas into the colon to improve visibility. CO2 is more quickly absorbed by the gastrointestinal tract and results in less bowel distension, giving the laparoscopic surgeon a better field of vision within the abdominal cavity. © Copyright Olympus. Used with permission. “Some patients who would have required a bowel resection can instead benefit from this A new, minimally invasive procedure that is a hybrid of colonoscopy and less invasive procedure. We’re laparoscopy is proving to be a safe and effective alternative to open colectomy using this combined technique (removal of part of the colon) for patients with benign colon polyps that are as a way for patients to avoid colectomy,” explains James not removable endoscopically. Yoo, M.D., a colorectal surgeon Patients who undergo this hybrid procedure experience less pain and often go at UCLA. “This procedure home after only one or two days. Scarring and wound complications are minimal involves tiny incisions for the as the laparoscopic surgeon makes only small, keyhole incisions in the abdomen laparoscopic instruments and patients stay in the hospital only rather than the long incision characteristic of a traditional colectomy. a day or two.” WWW.UCLAHEALTH.ORG 1-800-UCLA-MD1 (1-800-825-2631) Who can benefit from the procedure? Participating When a routine colonoscopy reveals polyps, they are usually removed at the Physicians time of the procedure as a precaution against their progression to cancer. -

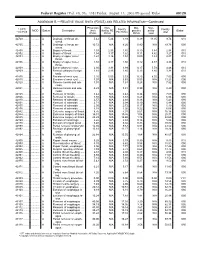

RELATIVE VALUE UNITS (RVUS) and RELATED INFORMATION—Continued

Federal Register / Vol. 68, No. 158 / Friday, August 15, 2003 / Proposed Rules 49129 ADDENDUM B.—RELATIVE VALUE UNITS (RVUS) AND RELATED INFORMATION—Continued Physician Non- Mal- Non- 1 CPT/ Facility Facility 2 MOD Status Description work facility PE practice acility Global HCPCS RVUs RVUs PE RVUs RVUs total total 42720 ....... ........... A Drainage of throat ab- 5.42 5.24 3.93 0.39 11.05 9.74 010 scess. 42725 ....... ........... A Drainage of throat ab- 10.72 N/A 8.26 0.80 N/A 19.78 090 scess. 42800 ....... ........... A Biopsy of throat ................ 1.39 2.35 1.45 0.10 3.84 2.94 010 42802 ....... ........... A Biopsy of throat ................ 1.54 3.17 1.62 0.11 4.82 3.27 010 42804 ....... ........... A Biopsy of upper nose/ 1.24 3.16 1.54 0.09 4.49 2.87 010 throat. 42806 ....... ........... A Biopsy of upper nose/ 1.58 3.17 1.66 0.12 4.87 3.36 010 throat. 42808 ....... ........... A Excise pharynx lesion ...... 2.30 3.31 1.99 0.17 5.78 4.46 010 42809 ....... ........... A Remove pharynx foreign 1.81 2.46 1.40 0.13 4.40 3.34 010 body. 42810 ....... ........... A Excision of neck cyst ........ 3.25 5.05 3.53 0.25 8.55 7.03 090 42815 ....... ........... A Excision of neck cyst ........ 7.07 N/A 5.63 0.53 N/A 13.23 090 42820 ....... ........... A Remove tonsils and ade- 3.91 N/A 3.63 0.28 N/A 7.82 090 noids. -

Laparoscopic Sentinel Node Mapping for Colorectal Cancer Using Infrared Ray Laparoscopy

ANTICANCER RESEARCH 26: 2307-2312 (2006) Laparoscopic Sentinel Node Mapping for Colorectal Cancer Using Infrared Ray Laparoscopy KOICHI NAGATA1, SHUNGO ENDO1, EIJI HIDAKA1, JUN-ICHI TANAKA1, SHIN-EI KUDO1 and AKIRA SHIOKAWA2 1Digestive Disease Center and 2Pathology Section, Showa University Northern Yokohama Hospital, Yokohama 224-8503, Japan Abstract. Background: Sentinel lymph node (SN) mapping colectomy (LAC). SNs were mapped by the submucosal by dye injection on conventional laparoscopy (CL) is often injection of dye on intra-operative colonoscopy, or by the precluded by the presence of mesenteric adipose tissue in use of a spinal needle and percutaneous subserosal injection patients with colorectal cancer. SN mapping on CL was of dye at a premarked site (pre-operative tattooing of compared with that on infrared ray laparoscopy (IRL) during polypectomy site with carbon). However, our experience laparoscopy-assisted colectomy (LAC). Patients and indicates that laparoscopic SN mapping by dye injection is Methods: Forty-eight patients with colorectal cancer who technically difficult because injection of the dye into the underwent LAC were enrolled. The tumor was identified by colon wall during LAC is cumbersome. Submucosal intra-operative fluoroscopy with marking clips. The tumor injection of dye on intra-operative colonoscopy makes LAC was stained intra-operatively by peritumoral injection of difficult and problematic. Distension of the small intestine indocyanine green dye. SNs were observed by CL and by IRL. with air on colonoscopy interferes with the operative field Results: In all 48 patients, dye injection and tumor and precludes laparoscopic procedures. Moreover, intra- localization during LAC were successful. The identification operative colonoscopic examinations require considerable of SNs on IRL was approximately five times better than that time, especially in patients with right-sided colon cancer. -

Incidental Drainage of a Periappendicular Abscess During Colonoscopy

UCTN – Unusual cases and technical notes E175 Incidental drainage of a periappendicular abscess during colonoscopy A 50-year-old man was referred to the of oral metronidazole and ciprofloxacin. A P. Figueiredo, V. Fernandes, J. Freitas outpatient colonoscopy clinic after a posi- computed tomography (CT) scan 1 week Department of Gastroenterology, tive fecal occult blood test during screen- after the procedure revealed no abnormal Hospital Garcia de Orta, Almada, Portugal ing for colorectal cancer. Colonoscopy, findings and the patient remained asymp- which was performed with the patient tomatic. sedated, revealed a 12-mm tumor covered Acute appendicitis is the most frequent References by normal, smooth mucosa at the site of acute abdominal emergency seen in de- 1 Oliak D, Yamini D, Udani VM et al. Can per- forated appendicitis be diagnosed preopera- the appendicular orifice. A biopsy was veloped countries. Its most common com- tively based on admission factors? J Gastro- taken, but this led to an immediate puru- plication is perforation and this may be intest Surg 2000; 4: 470–474 lent discharge occurring from the lesion followed by abscess formation [1]. Colo- 2 Ohtaka M, Asakawa A, Kashiwagi A et al. (●" Video 1). Therefore, a diagnosis of a noscopic diagnosis and treatment of a Pericecal appendiceal abscess with drainage periappendicular abscess was incidentally periappendicular abscess is rare [2]. In during colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 1999; 49: 107–109 established. this case a periappendicular abscess was 3 Antevil J, Brown C. Percutaneous drainage After the patient had recovered from the incidentally discovered and drained dur- and interval appendectomy. In: Scott-Turner sedation, he was specifically questioned ing a colonoscopy. -

Operative Laparoscopy

Operative Laparoscopy Technique Procedure involves the placement of a laparoscope (special telescope with a video camera attached) into the abdomen at the belly button. The pelvis including the uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries, bladder and appendix are all visualized to determine the source of the patient's problem. The treatment necessary is determined based upon what the surgeon sees during this exam. Potential treatments include ovarian cyst removal, ovarian removal, excision or destruction of endometriosis, and removal of scar tissue. Incisions 3-4 small incisions (less than one inch) are made on the abdomen for this procedure. Operative Time Operative times vary greatly depending on the findings at the time of surgery. Your surgeon will proceed with safety as his/her first priority. Average times range from 45-90 minutes. Anesthesia General anesthesia Preoperative Care Nothing by mouth after midnight The procedure is usually scheduled immediately after your menstrual period. Hospital Stay Day surgery or 23 hour observation Postoperative Care These guidelines are intended to give you a general idea of your postoperative course. Since every patient is unique and has a unique procedure, your recovery may differ. You will be prescribed both an anti-inflammatory and a narcotic pain medicine for postoperative use. We recommend that anti-inflammatory medications, such as ibuprofen, naproxen, etc., be used on a scheduled (regular) basis and that narcotic pain medicine be utilized on an "as needed" basis. Driving is allowed after your procedure only when you do not require the narcotic pain medicine to manage your pain. Patients may return to work in 2-3 days following the procedure. -

Immune Functions of the Vermiform Appendix

The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism Volume 3 Print Reference: Pages 335-342 Article 30 1994 Immune Functions of the Vermiform Appendix Frank Maas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Browse the contents of this volume of The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism. Recommended Citation Maas, Frank (1994) "Immune Functions of the Vermiform Appendix," The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism: Vol. 3 , Article 30. Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings/vol3/iss1/30 IMMUNE FUNCTIONS OF THE VERMIFORM APPENDIX FRANK MAAS, M.S. 320 7TH STREET GERVAIS, OR 97026 KEYWORDS Mucosal immunology, gut-associated lymphoid tissues. immunocompetence, appendix (human and rabbit), appendectomy, neoplasm, vestigial organs. ABSTRACT The vermiform appendix Is purported to be the classic example of a vestigial organ, yet for nearly a century it has been known to be a specialized organ highly infiltrated with lymphoid tissue. This lymphoid tissue may help protect against local gut infections. As the vertebrate taxonomic scale increases, the lymphoid tissue of the large bowel tends to be concentrated In a specific region of the gut: the cecal apex or vermiform appendix.