International Taxation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REPLACING CORPORATE TAX REVENUES with a MARK to MARKET TAX on SHAREHOLDER INCOME Eric Toder and Alan D

REPLACING CORPORATE TAX REVENUES WITH A MARK TO MARKET TAX ON SHAREHOLDER INCOME Eric Toder and Alan D. Viard October 2016 ABSTRACT We propose reducing the corporate tax rate to 15 percent and replacing the foregone revenue with a tax at ordinary income rates on the accrued, or mark-to-market income of American shareholders of publicly traded corporations, accompanied by an imputation credit for U.S. corporate income taxes paid. The proposal would dramatically reduce the tax significance of the source of corporate profits and the residence of corporations, both of which can be easily manipulated. Lowering the corporate tax rate to 15 percent would encouraging a capital inflow to the United States and reduce incentives to shift reported profits overseas and engage in inversion transactions while continuing to impose tax on foreigners who earn economic rents from investing in the United States. The proposal includes provisions for averaging of mark-to- market income, transition relief for firms that move from closely held to publicly traded status, and other measures to address the challenges of mark-to-market taxation. We estimate that the proposal would be approximately revenue-neutral and would make the distribution of the tax burden slightly more progressive. A revised version of the article was been published in the September 2016 issue of the National Tax Journal, Volume 69 (3), 701-731. The findings and conclusions contained within are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of the Tax Policy Center or its funders. I. INTRODUCTION This paper presents a proposal for reform of the taxation of corporate income. -

The Turkish Diaspora in Europe Integration, Migration, and Politics

GETTY GEBERT IMAGES/ANDREAS The Turkish Diaspora in Europe Integration, Migration, and Politics By Max Hoffman, Alan Makovsky, and Michael Werz December 2020 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG Contents 1 Introduction and summary 4 Key findings 9 Detailed findings and country analyses 34 Conclusion 37 About the authors and acknowledgments 38 Appendix: Citizenship laws and migration history in brief 44 Endnotes Introduction and summary More than 5 million people of Turkish descent live in Europe outside Turkey itself, a human connection that has bound Turkey and the wider European community together since large-scale migration began in the 1960s.1 The questions of immigra- tion, citizenship, integration, assimilation, and social exchange sparked by this migra- tion and the establishment of permanent Turkish diaspora communities in Europe have long been politically sensitive. Conservative and far-right parties in Europe have seized upon issues of migration and cultural diversity, often engaging in fearmonger- ing about immigrant communities and playing upon some Europeans’ anxiety about rapid demographic change. Relations between the European Union—as well as many of its constituent member states—and Turkey have deteriorated dramatically in recent years. And since 2014, Turks abroad, in Europe and elsewhere around the world, have been able to vote in Turkish elections, leading to active campaigning by some Turkish leaders in European countries. For these and several other reasons, political and aca- demic interest in the Turkish diaspora and its interactions -

Double Taxation of Corporate Income in the United States and the OECD

Double Taxation of Corporate Income in the United States and the OECD FISCAL Taylor LaJoie Elke Asen FACT Policy Analyst Policy Analyst No. 740 Jan. 2021 Key Findings • The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act lowered the top integrated tax rate on corporate income distributed as dividends from 56.33 percent in 2017 to 47.47 percent in 2020; the OECD average is 41.6 percent. • Joe Biden’s proposal to increase the corporate income tax rate and to tax long-term capital gains and qualified dividends at ordinary income rates would increase the top integrated tax rate on distributed dividends to 62.73 percent, highest in the OECD. • Income earned in the U.S. through a pass-through business is taxed at an average top combined statutory rate of 45.9 percent. • On average, OECD countries tax corporate income distributed as dividends at 41.6 percent and capital gains derived from corporate income1 at 37.9 percent. • Double taxation of corporate income can lead to such economic distortions as reduced savings and investment, a bias towards certain business forms, and debt financing over equity financing. • Several OECD countries have integrated corporate and individual tax codes to eliminate or reduce the negative effects of double taxation on corporate The Tax Foundation is the nation’s income. leading independent tax policy research organization. Since 1937, our research, analysis, and experts have informed smarter tax policy at the federal, state, and global levels. We are a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. ©2021 Tax Foundation Distributed under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC 4.0 Editor, Rachel Shuster Designer, Dan Carvajal Tax Foundation 1325 G Street, NW, Suite 950 Washington, DC 20005 202.464.6200 1 In some countries, the capital gains tax rate varies by type of asset sold. -

Creating Market Incentives for Greener Products Policy Manual for Eastern Partnership Countries

Creating Market Incentives for Greener Products Policy Manual for Eastern Partnership Countries Creating Incentives for Greener Products Policy Manual for Eastern Partnership Countries 2014 About the OECD The OECD is a unique forum where governments work together to address the economic, social and environmental challenges of globalisation. The OECD is also at the forefront of efforts to understand and to help governments respond to new developments and concerns, such as corporate governance, the information economy and the challenges of an ageing population. The Organisation provides a setting where governments can compare policy experiences, seek answers to common problems, identify good practice and work to co-ordinate domestic and international policies. The OECD member countries are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States. The European Union takes part in the work of the OECD. Since the 1990s, the OECD Task Force for the Implementation of the Environmental Action Programme (the EAP Task Force) has been supporting countries of Eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia to reconcile their environment and economic goals. About the EaP GREEN programme The “Greening Economies in the European Union’s Eastern Neighbourhood” (EaP GREEN) programme aims to support the six Eastern Partnership countries to move towards green economy by decoupling economic growth from environmental degradation and resource depletion. The six EaP countries are: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Republic of Moldova and Ukraine. -

Tax Policy Update 16 27 April

Policy update Tax Policy Update 16 27 April HIGHLIGHTS • European Parliament: Plenary discusses state of public CBCR negotiations 18 April • Council: member states freeze CCTB negotiations in order to assess its impact on tax bases 20 April • European Commission: new rules for whistleblower protection proposed, covers tax avoidance too 23 April • European Parliament: ECON Committee holds public hearing on definitive VAT system 24 April • European Commission: new Company Law Package with tax dimension published 25 April European Commission Commission kicks off Fair Taxation Roadshow 19 April The European Commission has launched a series of seminars on fair taxation, with a first event held in Riga on 19 April. These seminars bring together civil society, business representatives, policy makers, academics and interested citizens to discuss and exchange views on tax avoidance and tax evasion. Further events are planned throughout 2018 in Austria (17 May), France (8 June), Italy (19 September) and Ireland (9 October). The Commission hopes that the roadshow seminars will further encourage active engagement on tax fairness principles at EU, national and local levels. In particular, a main aim seems to be to spread the tax debate currently ongoing at the EU-level into member states as well. Commission launches VAT MOSS portal 19 April The European Commission has launched a Mini-One Stop Shop (MOSS) portal for VAT purposes. The new MOSS portal provides comprehensive and easily accessible information on VAT rates for telecom, broadcasting and e- services, and explains how the MOSS can be used to declare and pay VAT on such services. 1 Commission proposes EU rules for whistleblower protection, covers tax avoidance as well 23 April The European Commission has published a new Directive for the protection of whistleblowers. -

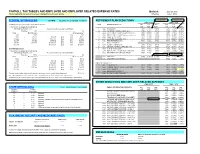

PAYROLL TAX TABLES and EMPLOYEE and EMPLOYER RELATED EXPENSE RATES Updated: June 27, 2012 *Items Highlighted in Yellow Have Been Changed Since the Last Update

PAYROLL TAX TABLES AND EMPLOYEE AND EMPLOYER RELATED EXPENSE RATES Updated: June 27, 2012 *items highlighted in yellow have been changed since the last update. Effective: July 1, 2012 FEDERAL WITHHOLDING 26 PAYS FEDERAL TAX ID NUMBER 86-6004791 RETIREMENT PLAN DEDUCTIONS 10.5% AT 50/50 10.5% AT 50/50 EMPLOYEE EMPLOYER (a) SINGLE person (including head of household) - CODE RETIREMENT PLAN DED OLD NEW DED OLD NEW If the amount of wages (after subtracting CODE RATE RATE CODE RATE RATE withholding allowances) is: The amount of income tax to withhold is: 1 ASRS PLAN-ASRS 7903 11.13% 10.90% 7904 9.87% 10.90% Not Over $83 ............................................................................................. $0 2 CORP JUVENILE CORRECTIONS (501) 7905 8.41% 8.41% 7906 9.92% 12.30% Over But not over - of excess over - 3 EORP ELECTED OFFICIALS & JUDGES (415) 7907 10.00% 11.50% 7908 17.96% 20.87% $83 - $417 10% $83 4 PSRS PUBLIC SAFETY (007) (ER pays 5% EE share) 7909 3.65% 4.55% 7910 38.30% 48.71% $417 - $1,442 $33.40 plus 15% $417 5 PSRS GAME & FISH (035) 7911 8.65% 9.55% 7912 43.35% 50.54% $1,442 - $3,377 $187.15 plus 25% $1,442 6 PSRS AG INVESTIGATORS (151) 7913 8.65% 9.55% 7914 90.08% 136.04% $3,377 - $6,954 $670.90 plus 28% $3,377 7 PSRS FIRE FIGHTERS (119) 7915 8.65% 9.55% 7916 17.76% 20.54% $6,954 - $15,019 $1,672.46 plus 33% $6,954 9 N/A NO RETIREMENT $15,019 ………………………………………………………$4,333.91 plus 35% $15,019 0 CORP CORRECTIONS (500) 7901 8.41% 8.41% 7902 9.15% 11.14% B PSRS LIQUOR CONTROL OFFICER (164) 7923 8.65% 9.55% 7924 38.77% 46.99% (b) MARRIED person F PSRS STATE PARKS (204) 7931 8.65% 9.55% 7932 18.50% 25.16% If the amount of wages (after subtracting G CORP PUBLIC SAFETY DISPATCHERS (563) 7933 7.96% 7.96% 7934 7.50% 7.90% withholding allowances) is: The amount of income tax to withhold is: H PSRS DEFERRED RET OPTION (DROP) 7957 8.65% 9.55% 0.24% AT 50/50 Not Over $312 ............................................................................................ -

Tax Avoidance Due to the Zero Capital Gains Tax

2 Capital gains tax regimes abroad—countries without capital gains taxes Tax avoidance due to the zero capital gains tax Some indirect evidence from Hong Kong BERRY F. C . H SU AND CHI-WA YUEN Consistent with its image as a free-market economy with minimal government intervention, Hong Kong is a city with low and simple taxation. Unlike most industrial and developed economies with full-fledged tax structures, Hong Kong has a relatively narrow tax base. It has direct taxes, which account for about 60% of the total tax revenue. These direct levies fall on earnings and profits and in- clude an estate duty. Hong Kong also has indirect taxes, which ac- count for the remaining 40%. These consist of rates, duties, and taxes on motor vehicles and so on.1 Nonetheless, Hong Kong has neither a sales or value-added tax nor a capital gains tax. In this paper, we explain the absence of the capital gains tax and provide some indirect evidence on the tax-avoidance effects induced by this fact. Notes will be found on pages 51–53. 39 40 International evidence on capital gains taxes Why is there no capital gains tax in Hong Kong? Under the British colonial rule, no tax was levied on capital gains in Hong Kong.2 This continues to be the case since the Chinese gov- ernment took over in 1997. During the pre-1997 (colonial) period, the tax structure in Hong Kong was based on the British tax system, which uses the source concept of income for the taxation of different kinds of in- come. -

Imports in GST Regime (Goods & Services Tax)

Imports in GST Regime (Goods & Services Tax) Introduction Under the GST regime, Article 269A constitutionally mandates that supply of goods, or of services, or both in the course of import into the territory of India shall be deemed to be supply of goods, or of services, or both in the course of inter-State trade or commerce. So import of goods or services will be treated as deemed inter-State supplies and would be subject to Integrated tax. While IGST on import of services would be leviable under the IGST Act, the levy of the IGST on import of goods would be levied under the Customs Act, 1962 read with the Custom Tariff Act, 1975. The importer of services will have to pay tax on reverse charge basis. However, in respect of import of online information and database access or retrieval services (OIDAR) by unregistered, non-taxable recipients, the supplier located outside India shall be responsible for payment of taxes (IGST). Either the supplier will have to take registration or will have to appoint a person in India for payment of taxes. Supply of goods or services or both to a Special Economic Zone developer or a unit shall be treated as inter-State supply and shall be subject to levy of integrated tax. Directorate General of Taxpayer Services CENTRAL BOARD OF EXCISE & CUSTOMS www.cbec.gov.in Imports in GST Regime (Goods & Services Tax) Importer Exporter Code (IEC): As per DGFT’s Trade Notice No. 09 The taxes will be calculated as under: dated 12.06.2017, the PAN of an entity would be used as the Import Particulars Duty Export code (IEC). -

Guide to Fiscal Information

Guide to Fiscal Information Key Economies in Africa 2014/15 Preface This booklet contains a summary of tax and investment information pertaining to key countries in Africa. This year’s edition of the booklet has been expanded to include an additional five countries over- and-above the thirty-five countries featured in last year’s edition. The forty countries featured this year comprise: Algeria, Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Chad, Congo (Brazzaville), Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Egypt, Ethiopia, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea Conakry, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Lesotho, Libya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritania, Mauritius, Morocco, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, South Africa, South Sudan, Swaziland, Tanzania, Tunisia, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Details of each country’s income tax, VAT (or sales tax), and other significant taxes are set out in the publication. In addition, investment incentives available, exchange control regimes applicable (if any) and certain other basic economic statistics are detailed. The contact details for each country are provided on the cover page of each country chapter/ section and also summarised on page 4, Tax Leaders in Africa. An introduction to the Africa Tax Desk (including relevant contact details) is provided on page 3, Africa Tax Desk. This booklet has been prepared by the Tax Division of Deloitte. Its production was made possible by the efforts of: • Moray Wilson, Adrienne Snyman and Susan Heiman – editorial management, content and design. • Bruno Messerschmitt, Musa Manyathi and Sarah Naiyeju – Deloitte Africa Tax Desk. • Deloitte colleagues (and Independent Correspondent Firm staff where necessary) in various cities/offices in Africa and elsewhere. -

Decentralising Immigrant Integration: Denmark's Mainstreaming Initiatives in Employment, Education, and Social Affairs

Decentralising Immigrant Integration Denmark’s mainstreaming initiatives in employment, education, and social affairs By Martin Bak Jørgensen MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE EUROPE Decentralising Immigrant Integration Denmark’s mainstreaming initiatives in employment, education, and social affairs By Martin Bak Jørgensen September 2014 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report, part of a research project supported by the Kingdom of the Netherlands, is one of four country reports on mainstreaming, covering Denmark, France, Germa- ny, and the United Kingdom. Migration Policy Institute Europe thanks key partners in this research project, Peter Scholten from Erasmus University and Ben Gidley from Compas, Oxford University. © 2014 Migration Policy Institute Europe. All Rights Reserved. Cover design: April Siruno Typesetting: Rebecca Kilberg, MPI No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from MPI Europe. A full-text PDF of this document is available for free download from www.mpieurope.org. Information for reproducing excerpts from this report can be found at www.migrationpolicy.org/about/copyright-policy. Inquiries can also be directed to [email protected]. Suggested citation: Jørgensen, Martin Bak. 2014. Decentralising immigrant integra- tion: Denmark’s mainstreaming initiatives in employment, education, and social affairs. Brussels: Migration Policy Institute Europe. TABLE OF CONTENTS -

FINANCE Offshore Finance.Pdf

This page intentionally left blank OFFSHORE FINANCE It is estimated that up to 60 per cent of the world’s money may be located oVshore, where half of all financial transactions are said to take place. Meanwhile, there is a perception that secrecy about oVshore is encouraged to obfuscate tax evasion and money laundering. Depending upon the criteria used to identify them, there are between forty and eighty oVshore finance centres spread around the world. The tax rules that apply in these jurisdictions are determined by the jurisdictions themselves and often are more benign than comparative rules that apply in the larger financial centres globally. This gives rise to potential for the development of tax mitigation strategies. McCann provides a detailed analysis of the global oVshore environment, outlining the extent of the information available and how that information might be used in assessing the quality of individual jurisdictions, as well as examining whether some of the perceptions about ‘OVshore’ are valid. He analyses the ongoing work of what have become known as the ‘standard setters’ – including the Financial Stability Forum, the Financial Action Task Force, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. The book also oVers some suggestions as to what the future might hold for oVshore finance. HILTON Mc CANN was the Acting Chief Executive of the Financial Services Commission, Mauritius. He has held senior positions in the respective regulatory authorities in the Isle of Man, Malta and Mauritius. Having trained as a banker, he began his regulatory career supervising banks in the Isle of Man. -

Tax Us If You Can 2012 FINAL.Pdf

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Murphy, R. and Christensen, J.F. (2012). Tax us if you can. Chesham, UK: Tax Justice Network. This is the published version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/16543/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] tax us nd if you can 2Edition INTRODUCTION TO THE TAX JUSTICE NETWORK The Tax Justice Network (TJN) brings together charities, non-governmental organisations, trade unions, social movements, churches and individuals with common interest in working for international tax co-operation and against tax avoidance, tax evasion and tax competition. What we share is our commitment to reducing poverty and inequality and enhancing the well being of the least well off around the world. In an era of globalisation, TJN is committed to a socially just, democratic and progressive system of taxation.