Arxiv:Astro-Ph/0103383V1 22 Mar 2001

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

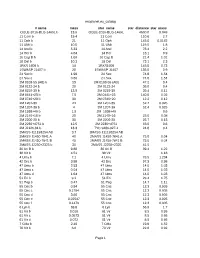

Exoplanet.Eu Catalog Page 1 # Name Mass Star Name

exoplanet.eu_catalog # name mass star_name star_distance star_mass OGLE-2016-BLG-1469L b 13.6 OGLE-2016-BLG-1469L 4500.0 0.048 11 Com b 19.4 11 Com 110.6 2.7 11 Oph b 21 11 Oph 145.0 0.0162 11 UMi b 10.5 11 UMi 119.5 1.8 14 And b 5.33 14 And 76.4 2.2 14 Her b 4.64 14 Her 18.1 0.9 16 Cyg B b 1.68 16 Cyg B 21.4 1.01 18 Del b 10.3 18 Del 73.1 2.3 1RXS 1609 b 14 1RXS1609 145.0 0.73 1SWASP J1407 b 20 1SWASP J1407 133.0 0.9 24 Sex b 1.99 24 Sex 74.8 1.54 24 Sex c 0.86 24 Sex 74.8 1.54 2M 0103-55 (AB) b 13 2M 0103-55 (AB) 47.2 0.4 2M 0122-24 b 20 2M 0122-24 36.0 0.4 2M 0219-39 b 13.9 2M 0219-39 39.4 0.11 2M 0441+23 b 7.5 2M 0441+23 140.0 0.02 2M 0746+20 b 30 2M 0746+20 12.2 0.12 2M 1207-39 24 2M 1207-39 52.4 0.025 2M 1207-39 b 4 2M 1207-39 52.4 0.025 2M 1938+46 b 1.9 2M 1938+46 0.6 2M 2140+16 b 20 2M 2140+16 25.0 0.08 2M 2206-20 b 30 2M 2206-20 26.7 0.13 2M 2236+4751 b 12.5 2M 2236+4751 63.0 0.6 2M J2126-81 b 13.3 TYC 9486-927-1 24.8 0.4 2MASS J11193254 AB 3.7 2MASS J11193254 AB 2MASS J1450-7841 A 40 2MASS J1450-7841 A 75.0 0.04 2MASS J1450-7841 B 40 2MASS J1450-7841 B 75.0 0.04 2MASS J2250+2325 b 30 2MASS J2250+2325 41.5 30 Ari B b 9.88 30 Ari B 39.4 1.22 38 Vir b 4.51 38 Vir 1.18 4 Uma b 7.1 4 Uma 78.5 1.234 42 Dra b 3.88 42 Dra 97.3 0.98 47 Uma b 2.53 47 Uma 14.0 1.03 47 Uma c 0.54 47 Uma 14.0 1.03 47 Uma d 1.64 47 Uma 14.0 1.03 51 Eri b 9.1 51 Eri 29.4 1.75 51 Peg b 0.47 51 Peg 14.7 1.11 55 Cnc b 0.84 55 Cnc 12.3 0.905 55 Cnc c 0.1784 55 Cnc 12.3 0.905 55 Cnc d 3.86 55 Cnc 12.3 0.905 55 Cnc e 0.02547 55 Cnc 12.3 0.905 55 Cnc f 0.1479 55 -

A Review on Substellar Objects Below the Deuterium Burning Mass Limit: Planets, Brown Dwarfs Or What?

geosciences Review A Review on Substellar Objects below the Deuterium Burning Mass Limit: Planets, Brown Dwarfs or What? José A. Caballero Centro de Astrobiología (CSIC-INTA), ESAC, Camino Bajo del Castillo s/n, E-28692 Villanueva de la Cañada, Madrid, Spain; [email protected] Received: 23 August 2018; Accepted: 10 September 2018; Published: 28 September 2018 Abstract: “Free-floating, non-deuterium-burning, substellar objects” are isolated bodies of a few Jupiter masses found in very young open clusters and associations, nearby young moving groups, and in the immediate vicinity of the Sun. They are neither brown dwarfs nor planets. In this paper, their nomenclature, history of discovery, sites of detection, formation mechanisms, and future directions of research are reviewed. Most free-floating, non-deuterium-burning, substellar objects share the same formation mechanism as low-mass stars and brown dwarfs, but there are still a few caveats, such as the value of the opacity mass limit, the minimum mass at which an isolated body can form via turbulent fragmentation from a cloud. The least massive free-floating substellar objects found to date have masses of about 0.004 Msol, but current and future surveys should aim at breaking this record. For that, we may need LSST, Euclid and WFIRST. Keywords: planetary systems; stars: brown dwarfs; stars: low mass; galaxy: solar neighborhood; galaxy: open clusters and associations 1. Introduction I can’t answer why (I’m not a gangstar) But I can tell you how (I’m not a flam star) We were born upside-down (I’m a star’s star) Born the wrong way ’round (I’m not a white star) I’m a blackstar, I’m not a gangstar I’m a blackstar, I’m a blackstar I’m not a pornstar, I’m not a wandering star I’m a blackstar, I’m a blackstar Blackstar, F (2016), David Bowie The tenth star of George van Biesbroeck’s catalogue of high, common, proper motion companions, vB 10, was from the end of the Second World War to the early 1980s, and had an entry on the least massive star known [1–3]. -

Search for X-Ray Emission from Bona-Fide and Candidate Brown

A&A manuscript no. (will be inserted by hand later) ASTRONOMY AND Your thesaurus codes are: ASTROPHYSICS 06(08.12.1; 08.12.2; 13.25.5) 11.9.2018 Search for X-ray emission from bona-fide and candidate brown dwarfs R. Neuh¨auser1, C. Brice˜no2, F. Comer´on3, T. Hearty1, E.L. Mart´ın4, J.H.M.M. Schmitt5, B. Stelzer1, R. Supper1, W. Voges1, and H. Zinnecker6 1 MPI f¨ur extraterrestrische Physik, Giessenbachstraße 1, D-85740 Garching, Germany 2 Yale University, Department of Physics, New Haven, CT 06520-8121, USA 3 European Southern Observatory, Karl-Schwarzschild-Straße 2, D-85748 Garching, Germany 4 Astronomy Department, University of California at Berkeley, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA 5 Universit¨at Hamburg, Sternwarte, Gojensbergweg 112, D-21029 Hamburg, Germany 6 Astrophysikalisches Institut, An der Sternwarte 16, D-14482 Potsdam, Germany Received 24 Sep 1998; accepted 10 Dec 1998 Abstract. Following the recent classification of the X- for a recent review. They continue to contract until elec- ray detected object V410 x-ray 3 with a young brown tron degeneracy halts further contraction. Depending on dwarf candidate (Brice˜no et al. 1998) and the identifica- metallicity and model assumptions made in for calculating tion of an X-ray source in Chamaeleon as young bona- theoretical evolutionary tracks, the limiting mass between fide brown dwarf (Neuh¨auser & Comer´on 1998), we inves- normal stars and brown dwarfs is ∼ 0.075 to 0.08 M⊙ tigate all ROSAT All-Sky Survey and archived ROSAT (Burrows et al. 1995, 1997, D’Antona & Mazzitelli 1994, PSPC and HRI pointed observations with bona-fide or 1997, Allard et al. -

THE STAR FORMATION NEWSLETTER an Electronic Publication Dedicated to Early Stellar Evolution and Molecular Clouds

THE STAR FORMATION NEWSLETTER An electronic publication dedicated to early stellar evolution and molecular clouds No. 44 — 15 May 1996 Editor: Bo Reipurth ([email protected]) Abstracts of recently accepted papers Lifetimes of Ultracompact HII Regions: High Resolution Methyl Cyanide Observations R.L. Akeson & J.E. Carlstrom Owens Valley Radio Observatory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA We observed the dense molecular cores associated with two ultracompact HII regions, G5.89 + 0.4 and G34.3 + 0.2, in the J=6–5 transitions of CH3CN to probe the temperature and density of the gas. Simultaneously, each region was observed in the J=1–0 transition of a CO isotope to probe the molecular column density. The molecular cores are found to have densities ∼ 106 cm−3 and kinetic temperatures of 90 K and 250 K, respectively. We also find possible evidence for infall of molecular gas toward the HII regions. The lifetime of the HII region ultracompact phase is critically dependent on the properties of the surrounding molecular gas. Based on the number of ultracompact HII regions versus the total number of O stars, it has been suggested that the lifetime of the ultracompact phase is inconsistent with spherical expansion confined only by the ambient medium. We show that for the molecular cloud parameters given above and including the effect of the shell of neutral material formed by the expansion, pressure confinement by the ambient medium may significantly increase the lifetime of the ultracompact phase of the HII regions. Accepted by Ap. J. Probing the initial conditions of star formation: The structure of the prestellar core L1689B P. -

Exoplanet.Eu Catalog Page 1 Star Distance Star Name Star Mass

exoplanet.eu_catalog star_distance star_name star_mass Planet name mass 1.3 Proxima Centauri 0.120 Proxima Cen b 0.004 1.3 alpha Cen B 0.934 alf Cen B b 0.004 2.3 WISE 0855-0714 WISE 0855-0714 6.000 2.6 Lalande 21185 0.460 Lalande 21185 b 0.012 3.2 eps Eridani 0.830 eps Eridani b 3.090 3.4 Ross 128 0.168 Ross 128 b 0.004 3.6 GJ 15 A 0.375 GJ 15 A b 0.017 3.6 YZ Cet 0.130 YZ Cet d 0.004 3.6 YZ Cet 0.130 YZ Cet c 0.003 3.6 YZ Cet 0.130 YZ Cet b 0.002 3.6 eps Ind A 0.762 eps Ind A b 2.710 3.7 tau Cet 0.783 tau Cet e 0.012 3.7 tau Cet 0.783 tau Cet f 0.012 3.7 tau Cet 0.783 tau Cet h 0.006 3.7 tau Cet 0.783 tau Cet g 0.006 3.8 GJ 273 0.290 GJ 273 b 0.009 3.8 GJ 273 0.290 GJ 273 c 0.004 3.9 Kapteyn's 0.281 Kapteyn's c 0.022 3.9 Kapteyn's 0.281 Kapteyn's b 0.015 4.3 Wolf 1061 0.250 Wolf 1061 d 0.024 4.3 Wolf 1061 0.250 Wolf 1061 c 0.011 4.3 Wolf 1061 0.250 Wolf 1061 b 0.006 4.5 GJ 687 0.413 GJ 687 b 0.058 4.5 GJ 674 0.350 GJ 674 b 0.040 4.7 GJ 876 0.334 GJ 876 b 1.938 4.7 GJ 876 0.334 GJ 876 c 0.856 4.7 GJ 876 0.334 GJ 876 e 0.045 4.7 GJ 876 0.334 GJ 876 d 0.022 4.9 GJ 832 0.450 GJ 832 b 0.689 4.9 GJ 832 0.450 GJ 832 c 0.016 5.9 GJ 570 ABC 0.802 GJ 570 D 42.500 6.0 SIMP0136+0933 SIMP0136+0933 12.700 6.1 HD 20794 0.813 HD 20794 e 0.015 6.1 HD 20794 0.813 HD 20794 d 0.011 6.1 HD 20794 0.813 HD 20794 b 0.009 6.2 GJ 581 0.310 GJ 581 b 0.050 6.2 GJ 581 0.310 GJ 581 c 0.017 6.2 GJ 581 0.310 GJ 581 e 0.006 6.5 GJ 625 0.300 GJ 625 b 0.010 6.6 HD 219134 HD 219134 h 0.280 6.6 HD 219134 HD 219134 e 0.200 6.6 HD 219134 HD 219134 d 0.067 6.6 HD 219134 HD -

![Arxiv:1912.05202V2 [Gr-Qc]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3836/arxiv-1912-05202v2-gr-qc-1893836.webp)

Arxiv:1912.05202V2 [Gr-Qc]

Stellar structure models in modified theories of gravity: lessons and challenges Gonzalo J. Olmo Depto. de F´ısica Te´orica and IFIC, Centro Mixto Universidad de Valencia-CSIC, Burjassot-46100, Valencia, Spain. Departamento de F´ısica, Universidade Federal da Para´ıba, 58051-900 Jo˜ao Pessoa, Para´ıba, Brazil. Diego Rubiera-Garcia Departamento de F´ısica Te´orica and IPARCOS, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, E-28040 Madrid, Spain Aneta Wojnar N´ucleo Cosmo-ufes & PPGCosmo, Universidade Federal do Esp´ırito Santo, 29075-910, Vit´oria, ES, Brasil Laboratory of Theoretical Physics, Institute of Physics, University of Tartu, W. Ostwaldi 1, 50411 Tartu, Estonia Abstract The understanding of stellar structure represents the crossroads of our theories of the nuclear force and the gravita- tional interaction under the most extreme conditions observably accessible. It provides a powerful probe of the strong field regime of General Relativity, and opens fruitful avenues for the exploration of new gravitational physics. The latter can be captured via modified theories of gravity, which modify the Einstein-Hilbert action of General Relativity and/or some of its principles. These theories typically change the Tolman-Oppenheimer-Volkoff equations of stellar’s hydrostatic equilibrium, thus having a large impact on the astrophysical properties of the corresponding stars and opening a new window to constrain these theories with present and future observations of different types of stars. For relativistic stars, such as neutron stars, the uncertainty on the equation of state of matter at supranuclear densities intertwines with the new parameters coming from the modified gravity side, providing a whole new phenomenology for the typical predictions of stellar structure models, such as mass-radius relations, maximum masses, or moment of inertia. -

Examination Paper for FY2450 Astrophysics

1 Department of Physics Examination paper for FY2450 Astrophysics Academic contact during examination: Rob Hibbins Phone: 94820834 Examination date: 31-05-2014 Examination time: 09:00 – 13:00 Permitted examination support material: Calculator, translation dictionary, printed or hand-written notes covering a maximum of one side of A5 paper. Other information: The exam is in three parts and part 1 is multiple choice. Answer all questions in all three parts. The percentage of marks awarded for each question is shown. An Appendix of useful information is provided at the end of the question sheet. Language: English Number of pages: 7 (including cover) Number of pages enclosed: 0 Checked by: ____________________________ Date Signature 2 Part 1. (total 30%) Part 1 is multiple choice. 3 marks will be awarded for each correct answer. No marks will be awarded for an incorrect or missing answer. On your answer sheet draw a table that looks something like, Question 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 1.10 Answer and insert your answer in the boxes. Only the answers will be marked. A B C D E The diagram above shows a colour (B-V) versus absolute visual magnitude (MV) plot for solar neighbourhood stars compiled from observations from the Hipparcos satellite. Five regions labelled A, B, C, D and E are highlighted. Which region on the HR diagram contains: (1.1) the stars with the smallest diameter (3%) (1.2) the stars that emit the greatest energy per second per unit surface area (3%) 3 (1.3) the stars with the largest diameter (3%) (1.4) the stars with the lowest mass (3%) (1.5) the main sequence stars with the smallest mass to luminosity ratio (3%) observations Star Spectral apparent observed parallax visual type magnitude colour distance half angle extinction mV (B-V)obs d p Av (mag) (mag) (pc) (arcsecs) (mag) A B0V +0.50 300 B A0V +7.6 +0.32 C F0V +10.8 0.0 D G0V +1.27 0.0250 E K0V 50 0.3 The table above lists some observed properties of five different main sequence stars labelled A, B, C, D and E. -

Open Mroute-Dissertation.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics RADIO OBSERVATIONS OF THE BROWN DWARF- EXOPLANET BOUNDARY A Dissertation in Astronomy and Astrophysics by Matthew Philip Route 2013 Matthew Philip Route Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2013 The dissertation of Matthew Philip Route was reviewed and approved* by the following: Alexander Wolszczan Evan Pugh Professor of Astronomy and Astrophysics Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Lyle Long Distinguished Professor of Aerospace Engineering, and Mathematics Director of the Computational Science Graduate Minor Program Kevin Luhman Associate Professor of Astronomy and Astrophysics John Mathews Professor of Electrical Engineering Steinn Sigurdsson Professor of Astronomy and Astrophysics Chair of the Graduate Program for the Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics Special Signatory Richard Wade Associate Professor of Astronomy and Astrophysics Donald Schneider Distinguished Professor of Astronomy and Astrophysics Head of the Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Although exoplanets and brown dwarfs have been hypothesized to exist for many years, it was only in the last two decades that their existence has been directly verified. Since then, a large number of both types of substellar objects have been discovered; they have been studied, characterized, and classified. Yet knowledge of their magnetic properties remains difficult to obtain. Only radio emission provides a plausible means to study the magnetism of these cool objects. At the initiation of this research project, not a single exoplanet had been detected in the radio, and only a handful of radio emitting brown dwarfs were known. -

Pleiades Low-Mass Brown Dwarfs: the Cluster L Dwarf Sequence

A&A 458, 805–816 (2006) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20065124 & c ESO 2006 Astrophysics Pleiades low-mass brown dwarfs: the cluster L dwarf sequence G. Bihain1,2, R. Rebolo1,2,V.J.S.Béjar1,3, J. A. Caballero1,C.A.L.Bailer-Jones4, R. Mundt4, J. A. Acosta-Pulido1, and A. Manchado Torres1,2 1 Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, c/ Vía Láctea, s/n, 38205 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain e-mail: [gbihain;rrl;zvezda;jap;amt]@ll.iac.es;[email protected] 2 Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Spain 3 GTC Project, Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias 4 Max-Planck-Institut für Astronomie, Königstuhl 17, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany e-mail: [calj;mundt]@mpia-hd.mpg.de Received 1 March 2006 / Accepted 3 August 2006 ABSTRACT Aims. We present a search for low-mass brown dwarfs in the Pleiades open cluster. The identification of Pleiades members fainter and cooler than those currently known allows us to constrain evolutionary models for L dwarfs and to extend the study of the cluster mass function to lower masses. 2 Methods. We conducted a 1.8 deg near-infrared J-band survey at the 3.5 m Calar Alto Telescope, with completeness Jcpl ∼ 19.0. The detected sources were correlated with those of previously available optical I-band images (Icpl ∼ 22). Using a J versus I − J colour–magnitude diagram, we identified 18 faint red L-type candidates, with magnitudes 17.4 < J < 19.7 and colours I − J > 3.2. If Pleiades members, their masses would span ∼0.040−0.020 M. -

254 — 13 February 2014 Editor: Bo Reipurth ([email protected]) List of Contents

THE STAR FORMATION NEWSLETTER An electronic publication dedicated to early stellar/planetary evolution and molecular clouds No. 254 — 13 February 2014 Editor: Bo Reipurth ([email protected]) List of Contents The Star Formation Newsletter Interview ...................................... 3 My Favorite Object ............................ 5 Editor: Bo Reipurth [email protected] Perspective ................................... 10 Technical Editor: Eli Bressert Abstracts of Newly Accepted Papers .......... 13 [email protected] Abstracts of Newly Accepted Major Reviews . 54 Technical Assistant: Hsi-Wei Yen Dissertation Abstracts ........................ 60 [email protected] New Jobs ..................................... 61 Editorial Board Meetings ..................................... 63 Summary of Upcoming Meetings ............. 66 Joao Alves Alan Boss Short Announcements ........................ 67 Jerome Bouvier New Books ................................... 68 Lee Hartmann Thomas Henning Paul Ho Jes Jorgensen Charles J. Lada Cover Picture Thijs Kouwenhoven Michael R. Meyer This image shows the blueshifted outflow cav- Ralph Pudritz ity from the embedded quadruple Class I source Luis Felipe Rodr´ıguez L1551 IRS5 based on Hα and [SII] images obtained Ewine van Dishoeck with the Subaru telescope images. Two short jets, Hans Zinnecker HH 154, are seen to emerge from the source region to the upper left. The outflow cavity has burst The Star Formation Newsletter is a vehicle for through the front of the cloud, exposing the rich fast distribution of information of interest for as- and complex Herbig-Haro shock structures within. tronomers working on star and planet formation A few faint knots from the HH 30 jet (outside the and molecular clouds. You can submit material field) are visible at the top of the image. The for the following sections: Abstracts of recently field is about 7×8 arcmin, corresponding to about accepted papers (only for papers sent to refereed 0.30×0.35 pc at the assumed distance of 150 pc. -

Brown Dwarfs in the Pleiades Cluster Confirmed by the Lithium Test

To app ear in ApJ Letters Brown Dwarfs in the Pleiades Cluster Conrmed by the Lithium Test R Reb olo E L Martn Instituto de Astrofsicade Canarias E La Laguna Tenerife Spain G Basri G W Marcy Department of Astronomy University of California Berkeley Berkeley CA USA and M R Zapatero Osorio Instituto de Astrofsicade Canarias E La Laguna Tenerife Spain email addresses rrliaces egeiaces basrisoleilb erkeleyedu gmarcyetoileb erkeleyedu mosorioiaces ABSTRACT We present m Keck sp ectra of the two Pleiades brown dwarfs Teide and Calar showing a clear detection of the nm Li resonance line In Teide we have also obtained evidence for the presence of the sub ordinate line at nm A high Li abundance log N Li consistent with little if any depletion is inferred from the observed lines Since Pleiades brown dwarfs are unable to burn Li the signicant preservation of this fragile element conrms the substellar nature of our two ob jects Regardless of their age their low luminosities and Li content place Teide and Calar comfortably in the astro-ph/9607002 1 Jul 1996 genuine brown dwarf realm Given the probable age of the Pleiades cluster their masses are estimated at Jupiter masses Subject headings op en clusters and asso ciations individual Pleiades stars abundances stars lowmass brown dwarfs stars evolution stars fundamental parameters Based on observations obtained at the WM Keck Observatory which is op erated jointly by the University of California and the Californian Institute of Technology Introduction In stellar interiors Li nuclei -

Stellar Structure Model in Hydrostatic Equilibrium in the Context of $ F

Stellar structure model in hydrostatic equilibrium in the context of f(R)-gravity Ra´ıla Andr´e∗ and Gilberto M. Kremery Departamento de F´ısica, Universidade Federal do Paran´a, 81531-980 Curitiba, Brazil. (Dated: August 29, 2017) In this work we present a stellar structure model from f(R)-gravity point of view capable to de- scribe some classes of stars (White Dwarfs, Brown Dwarfs, Neutron stars, Red Giants and the Sun). 2 This model was based on f(R)-gravity field equations for f(R) = R+f2R , hydrostatic equilibrium equation and a polytropic equation of state. We compared the results obtained with those found by the Newtonian theory. It has been observed that in these systems, where high curvature regimes emerge, stellar structure equations undergo modifications. Despite the simplicity of this model, the results were satisfactory. The estimated values of pressure, density and temperature of the stars are within those determined by observations. This f(R)-gravity model has been proved to be necessary to describe stars with strong fields such as White Dwarfs, Neutron stars and Brown Dwarfs, while stars with weaker fields, such as Red Giants and the Sun, were best described by the Newtonian theory. I. INTRODUCTION developed. In [19], using the method of perturbative con- straints and corrections of the form Rn+1, they showed The f(R)-gravity is a class of theories that represent that the predicted mass-radius relation for neutron stars an approach to gravitational interaction. In this con- differs from that calculated in the General Relativity. text, General Relativity (GR) has to be extended in or- In [20], the mass-radius diagram for static neutron star der to solve several issues.