Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Online Media and the 2016 US Presidential Election

Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Faris, Robert M., Hal Roberts, Bruce Etling, Nikki Bourassa, Ethan Zuckerman, and Yochai Benkler. 2017. Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election. Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society Research Paper. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33759251 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA AUGUST 2017 PARTISANSHIP, Robert Faris Hal Roberts PROPAGANDA, & Bruce Etling Nikki Bourassa DISINFORMATION Ethan Zuckerman Yochai Benkler Online Media & the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper is the result of months of effort and has only come to be as a result of the generous input of many people from the Berkman Klein Center and beyond. Jonas Kaiser and Paola Villarreal expanded our thinking around methods and interpretation. Brendan Roach provided excellent research assistance. Rebekah Heacock Jones helped get this research off the ground, and Justin Clark helped bring it home. We are grateful to Gretchen Weber, David Talbot, and Daniel Dennis Jones for their assistance in the production and publication of this study. This paper has also benefited from contributions of many outside the Berkman Klein community. The entire Media Cloud team at the Center for Civic Media at MIT’s Media Lab has been essential to this research. -

National Tracking Poll 2005100

National Tracking Poll #2005100 May 22-26, 2020 Crosstabulation Results Methodology: This poll was conducted from May 22-26, 2020, among a national sample of 1986 Registered Voters. The interviews were conducted online and the data were weighted to approximate a target sample of Registered Voters based on age, race/ethnicity, gender, educational attainment, and region. Results from the full survey have a margin of error of plus or minus 2 percentage points. Table Index 1 Table P1: Now, generally speaking, would you say that things in the country are going in the right direction, or have they pretty seriously gotten off on the wrong track? .................. 8 2 Table P3: Now, thinking about your vote, what would you say is the top set of issues on your mind when you cast your vote for federal offices such as U.S. Senate or Congress? . 11 3 Table POL1: Thinking about the November 2020 general election for president, Congress, and statewide offices, how enthusiastic would you say you are in voting in this year’s election? . 15 4 Table POL2: Compared to previous elections, are you more or less enthusiastic about voting than usual? 18 5 Table POL3: And how important do you think the November 2020 general election for president, Congress, and statewide offices will be? .................................. 21 6 Table POL4: Based on what you’ve seen, read, or heard, who do you think will win the November 2020 presidential election? ............................................ 24 7 Table POL5_1: Who do you trust more to handle each of the following issues? The economy . 27 8 Table POL5_2: Who do you trust more to handle each of the following issues? Jobs . -

Biden's Agenda and Indiana Needs

V26, N2 Thursday, Aug. 20, 2020 Biden’s agenda and Indiana needs to evolve, too, with HPI analyzes Dem’s additional steps to come so that we agenda; Harris’s meet the growing economic shocks. idealogical moorings We must prepare By BRIAN A. HOWEY now to take further INDIANAPOLIS – With Joe decisive action, in- Biden accepting the Democratic cluding direct relief, presidential nomination tonight, that will be large in Howey Politics Indiana reviewed his scale and focused campaign’s policy positions. We will on the broader do the same with President Trump health and stability and Vice President Pence next week of our economy.” during the virtual Republican Na- He added, “The tional Convention. American people Two areas that could have deserve an urgent, a major impact in Indiana are his robust, and profes- proposed pandemic response, and sional response to how the former vice president and the growing public senator will approach the epidemic health and economic that has receded from public view crisis caused by the over the past six months, the one coronavirus (CO- dealing with opioids. VID-19) outbreak. On the pandemic, Biden Continued on page 3 said, “This is an evolving crisis and the response will need Holcomb and race By BRIAN A. HOWEY INDIANAPOLIS – By any measure, Gov. Eric Holcomb’s mid-day address on Tuesday was extraordinary. Stating that Indiana stands at an “inflection point” and promising Hoosiers that he is prepared to become a racial “Donald Trump hasn’t grown “barrier buster,” the governor traced the nation’s racially charged lineage from Thomas Jefferson’s “Declaration of into the job because he can’t. -

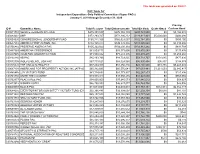

This Table Was Generated on 3/24/21. ID # Committee Name Total

This table was generated on 3/24/21. PAC Table 3a* Independent Expenditure-Only Political Committees (Super PACs) January 1, 2019 through December 31, 2020 Closing ID # Committee Name Total Receipts Total Disbursements Total IEs Made Debts Owed Cash on Hand C00571703 SENATE LEADERSHIP FUND $475,353,507 $476,355,109 $293,723,598 $0 $5,166,674 C00484642 SMP $372,293,747 $372,290,232 $229,911,901 $5,000,000 $406,686 C00504530 CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP FUND $165,741,326 $165,923,057 $142,784,335 $0 $409,100 C00637512 AMERICA FIRST ACTION, INC. $150,128,473 $149,372,836 $133,820,069 $0 $3,318,486 C00756882 PRESERVE AMERICA PAC $105,322,042 $104,430,334 $102,983,484 $0 $891,709 C00487363 AMERICAN CROSSROADS $81,809,711 $83,373,696 $79,476,089 $0 $137,498 C00487470 CLUB FOR GROWTH ACTION $71,990,842 $71,233,305 $65,439,435 $0 $1,259,660 C00492140 AB PAC $85,463,766 $84,733,025 $59,719,707 $101,645 $877,636 C00532705 INDEPENDENCE USA PAC $67,713,621 $68,024,060 $56,530,454 $96,837 $188,579 C00725820 THE LINCOLN PROJECT $87,404,908 $81,956,298 $49,186,930 $73,778 $5,448,609 C00687103 AMERICANS FOR PROSPERITY ACTION, INC.(AFP AC $60,382,095 $60,576,641 $47,633,481 $1,231,653 $2,340,817 C00486845 LCV VICTORY FUND $61,134,693 $61,173,937 $42,267,573 $0 $151,596 C00701888 UNITE THE COUNTRY $49,938,340 $48,980,275 $38,923,630 $0 $958,065 C00762377 PEACHTREE PAC $38,000,000 $37,945,073 $37,845,512 $0 $54,927 C00473918 WOMEN VOTE! $46,750,933 $46,927,077 $36,769,794 $0 $46,096 C00609388 BLACK PAC $44,044,054 $42,039,018 $31,783,484 $512,944 $2,352,147 C00688655 EVERYTOWN FOR GUN SAFETY VICTORY FUND (EVE$32,396,481 $32,309,097 $21,202,308 $6,618 $87,797 C00571588 RESTORATION PAC $25,107,533 $24,158,040 $19,777,020 $0 $1,834,748 C00741710 NRA VICTORY FUND, INC. -

Media Analysis of the US Election: August 2020 Insights from Pressrelations 2020 Introduction

2020 Media Analysis of the US Election: August 2020 Insights from pressrelations 2020 Introduction In cooperation with the Fraunhofer Institute for Communication, Information Processing and Ergonomics FKIE and NewsGuard, pressrelations is conducting am in-depth media analysis that sheds light on the role of disinformation in the 2020 US election. Time window of the qualitative analysis Link to the InfoBoard The basis for this quantitative, fully automated media analysis is formed by 426 online media sources from five countries. The data from 16 of those media sources was coded by pressrelations analysts, according to qualitative criteria. The selected media sources included eight US media sources and eight online media sources from Germany, Austria and Switzerland (D-A-CH), which were analyzed for the period from August 1 to August 31, 2020. In addition, TV coverage of CNN, FOX News and ARD was examined. 9/24/2020 PAGE 2 2020 Methodology This analysis includes the assessment and mapping of the media landscape from different perspectives and is based on extensive data collection from media reports made public on the Internet or on TV channels. The amount of news about the 2020 US election campaign is immense. The volume of articles therefore made it necessary to restrict the media set to a few select media sources. The selection of media was based on the potential reach and the volume of contributions of the respective sources. Despite this restriction, a total of 13,203 posts were coded in August alone. All articles that addressed at least one of the four candidates running for the American presidency and vice presidency were examined. -

Ipsos Poll Conducted for Bangor Daily News Maine Polling: 10.13.14

Ipsos Poll Conducted for Bangor Daily News Maine Polling: 10.13.14 These are findings from Ipsos polling conducted for the Bangor Daily News from October 6-12. State-specific sample details are below. The data are weighted to Maine’s current population voter data (CPS) by gender, age, education, and ethnicity. Ipsos’ Likely Voter model (applied to Voting Intention questions only) uses a seven-item summated index, including questions on voter registration, past voting behavior, likelihood of voting in the upcoming election, and interest in following news about the campaign. Statistical margins of error are not applicable to online polls. All sample surveys and polls may be subject to other sources of error, including, but not limited to coverage error and measurement error. Figures marked by an asterisk (*) indicate a percentage value of greater than zero but less than one half of one per cent. Where figures do not sum to 100, this is due to the effects of rounding. MAINE POLLING A sample of 1,004 Maine residents, including 903 Registered Voters (RVs) and 540 Likely Voters (LVs), age 18 and over in Maine was interviewed online. The credibility interval for a sample of 1,004 is 3.5 percentage points; 3.7 percentage points for a sample of 903; and 4.8 percentage points for a sample of 540. Q1. Thinking about the upcoming general election in November of this year, if the election for U.S. Senator from Maine were held today, for whom would you vote? Likely Voters Registered Democrats Republicans Independents (LV) Voters (RV) (RV) (RV) (RV) Susan Collins, Republican 56% 53% 34% 84% 50% Shenna Bellows, Democrat 31% 31% 56% 4% 21% Erick Bennett, Independent 4% 5% 1% 6% 11% Another candidate 1% 2% *% 2% *% Will not/do not plan to vote *% 1% 1% 1% *% Don’t know / Refused 7% 9% 7% 3% 18% Q2. -

Friday, July 10Th, 2020 TO: Interested Parties FROM: Reed Galen RE: State of the Race “Over These Next 11 Months, Our Efforts

Friday, July 10th, 2020 TO: Interested Parties FROM: Reed Galen RE: State of the Race “Over these next 11 months, our efforts will be dedicated to defeating President Trump and Trumpism at the ballot box and to elect those patriots who will hold the line. We do not undertake this task lightly, nor from ideological preference. We have been, and remain, broadly conservative (or classically liberal) in our politics and outlooks. Our many policy differences with national Democrats remain, but our shared fidelity to the Constitution dictates a common effort.” The Lincoln Project The New York Times December 17, 2019 The Lincoln Project launched six months ago in a different time and place in America. The country was preparing to experience its third impeachment trial in the history of the United States. The impeachment of President Donald J. Trump for abuse of power ended in political farce as Mitch McConnell and his supine Senate majority looked away from the clear evidence that President Trump had extorted a foreign government to assist his re-election. It is in that context, and the previous three years of Trump’s administration that The Lincoln Project began its efforts with a clear message: To rid American politics of Donald Trump and Trumpism in the November general election. At that moment, saving the Republic from the worst of Trump’s behavior was paramount. That goal was ambitious, but we knew even then that it would be an uphill fight. As the coronavirus made its way to our shores, Donald Trump’s inability to lead changed our outlook on how to conduct our efforts against him. -

Dupree Pleads to Dealing Meth

SPORTS COOK OF THE WEEK NESHOBA CENTRAL LADY LEONE INFLUENCED ROCKETS READY FOR TOURNEY BY GRANDMOTHER Basketball — Page 4B Alexis Leone — Page 1B Established 1881 — Oldest Business Institution in Neshoba County Philadelphia, Mississippi Wednesday, February 17, 2021 140th Year No. 7 **$1.00 FACING LIFE IN PRISON Dupree pleads to dealing meth By DUNCAN DENT Acting Special Agent in the result of an exten- nation’s primary tool felony pursuit, expired license Mississippi Bureau of Nar- [email protected] Charge of U.S. Immigration sive investigation, for disrupting and dis- tag, suspended driver's license, cotics, with assistance from and Customs Enforcement’s dubbed “Operation mantling major drug no insurance, possession of Drug Enforcement Adminis- A Philadelphia man has Homeland Security Investiga- Highlife,” which trafficking organiza- marijuana, vehicle, improper tration, Bureau of Alcohol, pleaded guilty to federal tions in New Orleans. began as an operation tions, targeting license tag- altered, possession Tobacco, Firearms and Explo- charges of possession with Although Dupree had pre- targeting illegal nar- national and regional of a controlled substance. He sives, Philadelphia Police intent to distribute metham- viously been convicted of sell- cotics distribution in level drug trafficking faced felony possession of a Department, Neshoba County phetamine and faces life in ing cocaine in Neshoba Coun- central Mississippi that organizations, and firearm in 2005. And in 2013 Sheriff’s Department, Nesho- prison, the Justice Department ty, he again sold and distrib- involved the distribu- Landon coordinating the nec- faced charges of conspiracy to ba County District Attorney’s announced. uted drugs (methampheta- tion of methampheta- essary law enforcement commit murder. -

Horse Race: Mayoral Battles Set Rematches in Jeffersonville, Anderson; Crowded Primaries in Muncie, Gary, South Bend by BRIAN A

V24, N23 Thursday, Feb. 14, 2019 Horse Race: Mayoral battles set Rematches in Jeffersonville, Anderson; crowded primaries in Muncie, Gary, South Bend By BRIAN A. HOWEY KOKOMO – Almost 120 Hoosier cities will Mayoral re- be electing mayors this year, with intense open matches include seat primaries taking shape in South Bend, Ko- Jeffersonville komo, Muncie, Noblesville Mayor Mike Moore and Elkhart. (far left) taking Democratic on Democrat Tom mayors Tom Henry of Fort Galligan (left), Wayne and Joe Hogsett of while in Anderson Indianapolis are seeking Kevin Smith is to protect the only seri- challenging Mayor ous power base remaining for their party. Hogsett Tom Broderick. is likely to face State Sen. Jim Merritt, while Fort Wayne Councilman John Crawford is a likely chal- will be seeking to burnish their credentials with milestone lenger to Mayor Henry, though the councilman will have to reelection bids. McDermott, Winnecke and Roswarski are fend off a primary challenge from business executive Tim not expected to be credibly challenged, with no opponents Smith. filing in Hammond and Evansville. And Mayors Thomas McDermott of Hammond, There could be fireworks in East Chicago, where Tony Roswarski of Lafayette, Duke Bennett in Terre Haute, Continued on page 3 Jim Brainard in Carmel and Lloyd Winnecke in Evansville Mayor Pete’s home base By JACK COLWELL SOUTH BEND – How South Bend Mayor Pete But- tigieg would fare in the 2020 Democratic presidential pri- mary in Indiana is uncertain. Voters in Iowa, New Hamp- shire and other states will determine before then whether “As someone who has always he is a viable contender. -

THE LINCOLN PROJECT Embargoed For: Contact

THE LINCOLN PROJECT Embargoed for: Contact: Tuesday, May, 12, 2020 Keith Edwards, 646-334-7929, [email protected] Press Release / Media Availability The Lincoln Project Expands Viral Ad "Mourning In America" to Target More Voters in Swing States: Ohio, Florida, and Wisconsin Tues., May 12, 2020 — The Lincoln Project today expanded the ad buy for “Mourning in America” — which so far has generated more than 20 million impressions among voters and the ire of President Trump — to four more cities, in three swing states. “Mourning in America" contrasts Ronald Reagan's 1984 iconic and optimistic political ad "Morning in America" with the devastation brought on by the Trump presidency. This next ad buy by the Lincoln Project will target voters in Wausau, WI; La Crosse WI; Columbus, OH; and Fort Meyers, FL. The Lincoln Project founders George Conway, Reed Galen, Jennifer Horn, Mike Madrid, Ron Steslow, John Weaver, Rick Wilson, Sarah Lenti, are available for comment. In 1984 Ronald Reagan’s campaign launched an iconic and memorable political ad called “Morning in America.” ‘Morning’ highlighted the positive impact of a first term Reagan presidency and presented an optimistic vision of an America that was prosperous and peaceful. Under Donald Trump, we instead face “Mourning in America.” “The Lincoln Project video highlights the effects of President Trump’s failure as a President and how he’s left the nation weaker, sicker, and teetering on the verge of a new Great Depression. In a time of deep suffering and loss, Donald Trump continues with his failed leadership and his inability to put the country before himself,” said Jennifer Horn, co-founder of The Lincoln Project. -

Population and Educational Attainment

Table of Contents Executive Summary ...................................................... 1 A Special Thanks Major Findings ............................................................. 1 To Our Sustaining Strategic Partners Context and Population Trends ..................................... 3 Educational Attainment Trends ..................................... 4 Migration Patterns ........................................................ 7 Rural Economic Development ....................................... 8 Conclusion .................................................................. 12 Sources....................................................................... 13 About Aroostook Aspirations Initiative ....................... 15 About Plimpton Research ........................................... 15 “The goals and aspirations of our young people are tied to the future prosperity of Aroostook County.” ~ Sandy Gauvin, Founder, Aroostook Aspirations Initiative Executive Summary Major Findings Aroostook County leaders are Context and Population Trends rightfully concerned about • Aroostook, the largest county in the eastern outmigration, particularly United States, makes up almost 20% of Maine’s land area. While the nation’s population among youth. Employers has grown by 30% since 1970, Maine’s has worry about who will replace increased by only 8%, and Aroostook County’s the region’s aging workforce, has declined by 20%. as economic developers • Aroostook County is losing its young work to diversify the area’s population faster than Maine -

Academic Affairs Signature Research Areas

0 Academic Affairs Signature Research Areas I. Area of submission: Signature Research: Advanced Materials for Infrastructure and Energy II. Applicant information: Lead Faculty/Researchers: Name: Dr. Habib Dagher, P.E. Title/Department: Director, University of Maine’s Advanced Structures and Composites Center Phone: (207) 581-2123 E-mail: [email protected] Name: Dr. Stephen Shaler Title/Department: Director, School of Forest Resources and Assoc. Director, UMaine Composites Center Phone: (207) 581-2886 E-mail: [email protected] Name: Larry Parent Title/Department: A. Director, UMaine Advanved Structures and Composites Center Phone: (207) 581-2886 E-mail: [email protected] Name: Dr. Douglas Gardner Title/Department: Professor of Forest Operations, Bioproducts & Bioenergy, UMaine Composites Center Phone: (207) 581-2846 E-mail: [email protected] Name: Dr. William Davids Title: John C. Bridge Professor and Chair of Civil & Environmental Engineering, UMaine Composites Center Phone: (207) 581-2116 E-mail: [email protected] Name: Dr. Eric Landis Title/Department: Frank M. Taylor Professor of Civil Engineering, UMaine Composites Center Phone: (207) 581-2173 E-mail: [email protected] Name: Dr. Roberto Lopez-Anido Title/Department: Malcolm G. Long Professor of Civil & Env. Engineering, UMaine Composites Center Phone: (207) 581-2119 E-mail: [email protected] Name: Dr. Krish Thiagarajan Title/Department: Alson D. and Ada Lee Correll Presidential Chair in Energy & Professor, UMaine Composites Center Phone: (207) 581-2167 E-mail: [email protected] 1 INTRODUCTION The UMaine Composites Center is an interdisciplinary research center dedicated to the development of novel advanced composite materials and technologies that rely on Maine’s manufacturing strengths and abundant natural resources.